Inside Mac OS X Snow Leopard: Malware Protection

Malware Protection?

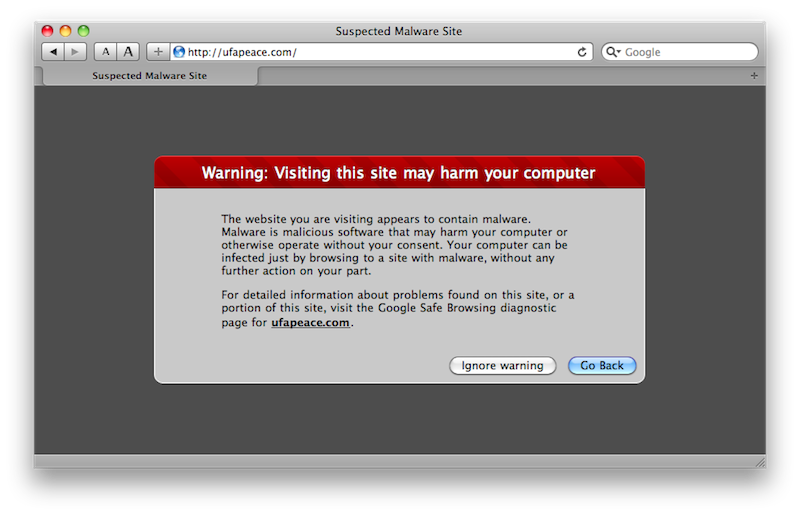

Safari, like other modern browsers, already flags certain websites that are known to be used to distribute malicious software (below). The previous release of Leopard also already flags Internet downloads with metadata that alerts users that what they are opening was downloaded from the web, citing where and when.

What's new in Snow Leopard is an additional warning when disk images are opened containing known malware installers. However, there is no real malware problem on the Mac, in part because it's hard to write viral code that infects Mac OS X and very easy for Apple to roll out a patch that closes any discovered holes.

"Mac bugs aren’t really valuable"

Shortly after security experts disclose their pet exploit discoveries at black hat security competition events, the highly publicized exploits are patched relatively quickly by Apple, although many report that they wish the company would step up its efforts on that front to close any potential window allowing theoretical attacks.

The fact that there are no real problems on the Mac makes every potential exploit discovery newsworthy, unlike the scores of new exploits regularly discovered for other platforms. In the wake of the Pwn2Own contest, Mac security expert Charlie Miller reiterated, "I'd still recommend Macs for typical users as the odds of something targeting them are so low that they might go years without seeing any malware, even though if an attacker cared to target them it would be easier for them."

Despite this exaggerated publicity surrounding Mac malware discoveries, there's simply no sustainable business model for profiting from malware on the Mac. In Miller's words, "Mac bugs aren’t really valuable."

That is particularly the case in comparison to Windows, where security holes abound in the massive sea of the unmanaged installed base of generic PCs, updates are not as easy to install, and there is an active market for ready-made virus code used to deliver malware payloads.

Most of the iceberg is under water

Microsoft's installed base of a billion Windows PCs is a fertile base for spammers and identity thieves to set up their virus-distributed operations. While Microsoft has invested heavily in securing Windows Vista/7, adoption of modern versions of Windows is very low. This has severely diluted the billions Microsoft has invested over the past decade to fix Window's show stopper security problems.

As noted earlier, even among big spending gamers with higher-end PCs, Vista's penetration has only reached a weak 36% after nearly three years. W3Schools reports the combined use of Vista/7 reaching just 21% in August 2009 among its web stats of ten million visiting developers.

That means more than two-thirds of the general PC population worldwide is still using Windows XP, and many of those Internet-connected but security-challenged machines are not regularly patched and will never be upgraded to Vista or Windows 7.

Window's security problem isn't simply a product of its popularity, but rather a result of Microsoft's catering to the low end of the mass market to deliver a ubiquitous product suffering from engineering lapses, from Active X to the Registry to invisible and unauthorized background software installation, all problems that have resulted in a platform riddled with serious security breeches.

Microsoft isn't just a victim of malicious software vendors however; it has also distributed both its own and third party adware and spyware, from Windows Genuine Advantage to Alexa. In 2005, it even entered talks to buy the notorious Claria, which resulted in Microsoft's Windows AntiSpyware conveniently reclassifying that company's Gator and other malware titles as "non-threatening" and suggested that users ignore the problem.

Prior to becoming a potential benefactor of the firm's malware business, Microsoft recommended that Windows users quarantine Claria's malware.

No ice on the horizon in Cupertino

The iPhone demonstrates that Apple can achieve a significant share of a market without creating a Windows-like petri dish of viral malware as a result. If the iPhone can avoid a security plague while capturing 10% to 25% of the smartphone hardware market (and a majority portion of smartphone software activity), it appears Apple's Mac platform should also have room to safely double several times.

Panicked warnings about an inevitable flood of Mac malware have been regularly sounded since 2004, but dramatic advances in Mac market share have simply not resulted in similar growth in malware threats relative to those on the Windows platform. Instead, the Mac's security has been improving.

Snow Leopard continues the development of the Mac platform to include an immune system that helps prevent users even from infecting themselves inadvertently while trying to download porn or obtain an illicit copy of iWork. This issue, of trojan user trickery, has no direct connection with the separate issue of software flaws and vulnerabilities that can result in direct exploits from outside attackers.

Security Fears and Exploitation

Security experts who discover theoretical exploits and flaws in operating systems, including Miller, report that Mac OS X offers fewer security features overall than Windows Vista, but that it is "safer" because nobody is taking advantage of those holes.

It is true that in certain areas, Microsoft has delivered security features in Windows Vista/7 that have no equivalent Snow Leopard. Uninformed writers who interview these software exploit experts often confuse the issue by associating "exploits" with "viruses," and "automated viral attacks" with "people being tricked into installing malicious software themselves."

As a result, they end up falsely claiming that the Mac is on a similar level as Windows as far as malware existence, which is not remotely true; they ignore that Windows PCs are still bombarded with viruses, none of which has ever hit Mac users; and they claim that the theoretical security of Windows is better than that of Mac OS X, apparently having forgot that the very "do-it-to-yourself trojan installation problem" they inspire fear about on the Mac is much worse on Windows, and that nothing in Vista/7's fancy exploit-closing technologies can stop users from manually installing their own casual malware trojans.

Be careful what you ask for

The Mac platform isn't under attack from virus writers who exploit vulnerabilities because there is no business model for investing in attacking Macs. The only examples of Mac malware ever cited are non-viral, malicious software installers that must trick users into authorizing their installation.

However, the only way an operating system can prevent users from installing their own malware is to specifically regulate the software users can install. That's what the iPhone does; users can't install unapproved software without first defeating the iPhone's security system via jailbreaking.

Most Mac users wouldn't want Apple preventing them from installing any software that wasn't signed and approved by Apple. Yet some pundits who complain that Apple went too far in restricting iPhone apps are also inspiring fear that the iPhone is a potential security risk when jailbroken, effectively arguing for the right to eat cake while keeping it around, too.

Mac Antivirus?

Antivirus vendors Kaspersky, Symantec, and particularly Intego have all tried to suggest that Apple's new alert targeting a couple of known malware installers is somehow an admission that Mac users need to buy antivirus software to eat up 10% of their processor while looking for problems that don't exist.

However, with Snow Leopard's built-in, updatable malware blacklist managed by the operating system, the Mac now has a security profile closer to the iPhone, without any need for a whitelist requiring an app approval process like the App Store.

Mac and iPhone users are not theoretically impervious to any possible attack, but both are well ahead of the competition. Macs are not suffering from real-world problems (as Windows does) and the iPhone is secured from the wide-open potential for malicious assault (as Android is). With Snow Leopard, Apple has simply made the business case for building new Mac malware that much less attractive to thugs.

Bugs in the bug-catchers

The fact is that virtually all software has some potential for exposing exploitable vulnerabilities. The threat of vulnerabilities in antivirus software is particularly dangerous because antivirus typically requires greater access privileges to do its job than most user software does.

On Windows, the moderate risk of antivirus exploits are outweighed by the benefit antivirus provides. On the Mac however, installing antivirus software has little upside and can instead expose its own vulnerabilities, demand performance-sapping overhead, introduce other bugs or incompatibilities into the system and simply get in the way.

One obvious example is McAfee Virex, which Apple formerly bundled with .Mac. It doesn't anymore because Virex didn't really provide any valuable security service, it flagged false positives and it introduced other bugs.

A simple Google search for “antivirus vulnerability†provides a long list of critical vulnerabilities introduced by antivirus products from virtually every brand in the business: Avast, AVG, BitDefender, McAfee, Norton, ClamAV, Symantec, F-Secure, F-Prot, Kaspersky Labs, and Trend Micro. There are flaws in the antivirus engines and sometimes even new vulnerabilities that are exposed when updates are downloaded.

A recent vulnerability discovered in Panda Security's ActiveScan online service for Windows users allowed remote execution of code. Last year, a study of antivirus vulnerabilities unearthed hundreds and called into question how antivirus vendors report and patch their own software's flaws.

The problem with antivirus vulnerabilities is separate from the additional risks of false positives (sometimes just a false alarm, sometimes disabling important system files which cause serious problems), false negatives (failing to stop an infection), and just being in the way and sapping system performance. The claim that users should just “install something†to feel safe is simply wrong.

Preparing for the future

Despite all the uproar about theoretical exploits made possible by software vulnerabilities in either Apple's own code or the open source code Apple incorporates into Mac OS X, the lack of any business model to support the creation of such exploits has prevented Mac users from being attacked.

For this reason, third-party Mac antivirus software largely only offers most users the potential of installing new vectors for exploit. There are no real malware risks that are currently addressed on the Mac by third party antivirus tools apart from scanning for Windows or Office viruses.

Snow Leopard's launch is now being set for an overshadowing by tomorrow's iPod and iTunes event. However, Apple is also continuing to build upon the new foundation laid with Snow Leopard, preparing the next minor "service pack" 10.6.1 update and working to build the next generation of new hardware to further exploit capabilities enabled in the new release.

Among these are support for built in WWAN mobile wireless networking, far more RAM, and fully exploitable, advanced GPUs. Apple is also advancing Snow Leopard Server, and will also be using the advances delivered in Snow Leopard to improve the iPhone and Apple TV, as future articles will examine.

Daniel Eran Dilger is the author of "Snow Leopard Server (Developer Reference)," a new book from Wiley available now for pre-order at a special price from Amazon.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Sponsored Content

Sponsored Content

Christine McKee

Christine McKee