iPhone 4 Review: 2 - the Phone & FaceTime

In this series

The phone in iPhone 4

Standing in line for hours (five and a half to be exact; I did not expect to wait more than a half hour when I arrived), I was struck by how many people were willing to spend so much of their day waiting for the new iPhone.

No other class of product commands such attention, and it hit me why in line: there is nothing else we interact with on such a personal and continuous basis all day long as our smartphones. Apple very clearly encourages launch day lines for marketing purposes, but it couldn't maintain such theatrics year after year if its iPhones weren't living up to the hype. Interviews suggest more than 70% of those waiting in launch day lines were existing iPhone users.

Of course, the primary reason we started carrying mobile phones was to be able to make calls and be contacted. Ironically, the most famous smartphone is also one of the worst performing phones, at least in the US. AT&T's network, which greeted the original iPhone as a brand new amalgamation of GSM providers in the US, started out well behind Verizon's CDMA network in terms of 3G buildout. It is now struggling to keep up with the massive demand of what is collectively the world's most mobile-greedy device. That adds up to a perfect storm of terrible waiting to greet Apple's latest and greatest phone.

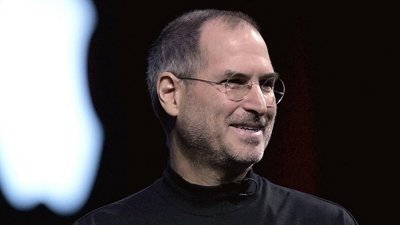

Steve Jobs said on stage at WWDC that AT&T is handling more mobile data than all the other US carriers put together. At the same time, AT&T is also delivering the fastest national network, and the only one compatible with the GSM/UMTS mobile technology used by most foreign networks internationally (making roaming possible, albeit expensive, for users, while also facilitating the manufacture of one iPhone model for Apple). There's still major problems in some service areas though, and AT&T's efforts to upgrade its network can't seem to come fast enough.

Light at the end of iPhone's US tunnel

They are improving however. In San Francisco, holes where EDGE was hard to get last year are now showing up as usable 3G. There's also AT&T's Microcell 3G product, which can help fill a dead space in one location, although it costs a one time fee of $150, and you can't set up more than one or locate it anywhere else apart from your home billing address. It also bills 3G mobile data use as part of your monthly plan allotment, although if you have Internet access for your Microcell 3G, you're probably also using WiFi for your data, not its 3G data service.

Another factor in iPhone 4's favor is that it now supports both HSDPA (like last year's iPhone 3GS) as well as HSUPA, a combination that enables it to take full advantage of AT&T's network speed edge over Verizon. Outside the US, support for these "3.5G" standards means users will see even faster mobile network speeds: up to 7.2 Mbps down and 5.8 Mbps up. That's faster than most American's broadband Internet service. Even here in the US, iPhone 4 is delivering uploads of up to 10 times what the previous iPhone was capable of delivering, an improvement that will be an important factor to users who want to send MMS pictures and videos, email documents, or upload photos and movies to sites like MobileMe and YouTube.

Jobs indicated that the new antenna design of iPhone 4, which leverages its peripheral stainless steel band, would also help to improve reception, and early reviews have noted that to be the case. Apple also told early reviewers that it had worked to optimize how the device selected nearby towers.

iPhone 4's hardware recall campaign

The flip side to these improvements appears to be that some early bugs have hit both how iOS 4 reports signal bars (its not very reliably accurate) and how it chooses the frequency it wants to use (its sometimes fails completely, indicating no service rather than switching correctly). This sort of thing can be fixed in the baseband software, and reports indicate that Apple is working to get out its first update as soon as this week. Every new iPhone so far got its first software update in about a month after its launch, so if those reports are correct, this could be the fastest first fix Apple has delivered.

That might be critical because iPhone 4 is facing its first "product recall campaign" much earlier than usual this year, too. Recall that every iPhone has been hit with a story that claimed a major hardware defect, and suggested that Apple would face a major and expensive hardware recall:

- The original iPhone was targeted by a Richard Windsor research note suggesting that iPhones might suddenly stopped working in the first three to six months due to a heat sensitive film failure in the screen, despite the fact that there wasn't any such film even present in its design.

- iPhone 3G was also targeted by a Richard Windsor research note, this time suggesting that iPhone hardware would fail because of the faulty design of its Infineon chips, a problem that supplier denied and which ultimately proved to be either just speculation or pure invention. Apple later released a software update that resolved many of the dropped call issues.

- iPhone 3GS was hit by widespread reports of overheating, then fears that faulty batteries would cause a recall. Neither problem panned out as a real issue, although Apple replaced batches of its mini power adapters after some plugs broke off.

The idea that iPhone 4 has a significant hardware defect because some users report being able to block their reception using their hand (when the phone is used without a case) hasn't yet been officially addressed by Apple. However, the overwhelming majority of reviews are reporting that iPhone 4 has significantly better reception and fewer dropped calls than previous iPhones. If the antenna design were really flawed, those improvements shouldn't be so widely observed.

Cell phone bars

The rumor campaign against iPhone 4's antenna has even infected the legitimate news media, with the UK's DailyMail printing an entire article (which was later pulled) worrying that "iPhone 4 may be recalled," based upon a comment posted to Twitter by a joke account purporting to be Steve Jobs.

Last week, the New York Times published a report based largely upon an article by Gizmodo, without noting the site's ongoing feud with Apple, including its being refused media entry to the WWDC keynote.

Brian Lam, the Gizmodo editor who lost his existing phone in a police investigation related to the iPhone prototype theft, said his site was "paying attention to the [iPhone 4] antenna issue because it could be a big deal," but also said he bought a new iPhone 4 and is now able to place "hours of calls" that he could not place in the same location with previous generations of iPhones.

At the heart of the issue is the fact that the cell phone signal bars reported by mobile phones do not function like a gas tank meter, as most users might assume. Instead, they work more like a reserve tank light. Five full bars can indicate anything from an ideal signal down to just enough to complete a call. As bars drop, the signal meter is reporting that call quality loss is imminent. The reason why some users see no difference (particularly when they're near a strong signal source, such as a Microcell 3G appliance) and others can drop from five bars to none just by covering the antenna with their hand placement, is that the latter group's five bars are indicating much less signal to start with.

So far, the reports of the iPhone 4's antenna issues have been based entirely upon unscientific testing by users who don't understand how their signal bars work. Comments by engineers Steve Gibson and Simon Byrnand explain that the signal bar meter does not quantify a specific amount of signal available (very different signal variations can still result in five bars being observed).

That means that videos posted by users that show a drop in signal related to hand placement are nearly worthless as evidence of a real problem. Users don't need bars to appear on their phone; they need a strong enough signal to place a call or send and receive data.

Gibson writes, "Apple’s '5-bars' cellular signal strength display is not showing the full range of possible, or even typical, received cellular signal strength. It is only showing the bottom end of the full range of possible reception strength."

No tests so far have shown that a hardware issue is to blame for reception problems on iPhone 4. In my own testing, I could not isolate any hand placement that prevented calls from working or lowered the reported data rates available, nor even could I force down the signal bars with a "death grip."

On the EDGE of a cliff

At the same time, there are still too many places I get service bars but can't maintain a good enough signal to make an actual call. There are many potential reasons for this, including the fact that one can get a strong mobile signal and still not be able to talk or send and receive data because the carrier's backhaul network is overcrowded. It's like being able to quickly jump on the freeway via an onramp with no traffic, only to be stuck in a jam that prevents you from actually getting anywhere further down the road.

Whether the problems I observed are related to iOS 4 software, an issue with AT&T's towers or their uplinks, or some combination of factors, it prevents iPhone 4 from being easy to unreservedly praise for the main purpose it serves. No matter how great the hardware, if the phone doesn't work as a phone where you need it to, it isn't a very good phone.

Of the first twenty calls I made with iPhone 4, every single one of them terminated itself prematurely except for one: a FaceTime call I made independent of AT&T's network. The experience was almost enough to make me return my fancy iPhone 4 and hold my nose through an Android experience on a lessor HTC phone with flashy hardware features that don't quite work and a terrible user interface on a high pixel resolution but low 16-bit color resolution screen, just so I could actually place calls (and do things like tether both my notebook and iPad, something I can't do with iPhone 4 unless I jailbreak it).

AT&T's network is clearly the weakest link for iPhone 4, almost in a dramatic Greek hero sort of fashion: the mythical magical mobile computer-phone dipped in the river Styx all but for its mobile contract. AT&T's issues create the perception that this amazing device can do no wrong, apart from when the Fates take circumstances out of the hands of Apple's own engineers and hand them to AT&T.

Apple isn't perfect either

Of course, in reality-land Apple's own software suffers some flaws of its own, ranging from petty to significant, which can't be blamed on AT&T. Users have reported a series of iOS 4 issues ranging from battery life (occasionally getting better, often getting worse, and frequently simply being reported wrong); data sync issues (calendar sync failures that add old events, inability to edit Contact information, inability to get Notes to sync on occasion); spurious warnings about the device overheating, despite no obvious thermal issues; reports that the proximity sensor may not turn off the display reliably when making a call (a problem I did not observe); and of course the Death Grip issue that appears to be related to or at least accentuated by iOS 4's baseband software flaws.

My initial dropped call problems occurred in the walk from the metro station to my house, a notorious valley of terrible cellular reception exacerbated by a surrounding neighborhood full of too many iPhone users. Further testing backed me away from the cliff, as both the call quality (thanks to new noise cancellation) and call performance seem to be significantly improved over the iPhone 3GS, at least in areas where you give it a signal to work with. In fact, while testing how the phone works when it loses its signal, I found iPhone 4 was able to grab and hold a connection in places where my iPhone 3GS could not at all.

Still, if you don't have a decent signal to work with, your iPhone 4 experience will be utterly devastating. No matter how great the phone's design and implementation, if you lack usable service you're stuck paying big bills every month for an essential piece of hardware that isn't doing its job.

On page 2 of 2: Calls without the carrier: FaceTime.

Despite its fancy hardware, the core feature that is getting people into the Apple Store for iPhone 4 is FaceTime. It works great, but requires a WiFi connection. The reason: it delivers a good picture and good audio, which demand high bandwidth and low latency. No 3G network will currently deliver that to a population of millions of users, and certainly not cost effectively.

Alternative voice chat services (including both 3GPP mobile video chat on Nokia phones, or VoIP services like Fring that can be installed on one of the relatively few other US phones with a front facing camera, such as the HTC Sprint EVO 4G) trade off call quality for being able to make video calls anywhere. However, the iPhone's heavy dependance on AT&T in the US, and the costs that would be involved in placing regular video chats over the no longer unlimited contracts available, simply make aiming for a WiFi-only deployment the only step that could possibly launch the new service adequately for iPhone users.

Making a FaceTime call requires WiFi, but it also requires mobile service. Prior to activating my iPhone 4, there was no possible way to initiate a FaceTime connection. In Apple's documentation, it also notes that there's no way to start a FaceTime call without disclosing your phone number to the other party. Clearly, the phone network is being used to set up the call, even when you start a call directly from Contacts.

This will eventually change, as there's no way Apple can not add this killer feature to both the upcoming iPod touch 4 and to the company's iChat AV product on the Mac, particularly given the company's openness in working to get other mobile makers in on the same standards-based protocol for video chats. For now however, setting up a FaceTime conversation depends upon the mobile phone network, meaning you can not use the feature in places where you have WiFi but no cellular service. That's pretty disappointing given how easy it is to find holes in AT&T's service.

(Correction: after its initial connection, iPhone 4 FaceTime doesn't need a mobile signal to work)

Using FaceTime

The upside is that you don't really need good cellular service; you just need to be able to start a call. In many cases, bad AT&T service isn't a problem of zero service, it's just that you can't always reliably maintain a call as you move around in the troublesome spots between buildings or cellular tower shadows. If you try to make a FaceTime call and have no cellular signal at all, it will ring and ring (with that awful high pitch chirping from iChat) but never show up on the other end, not even as a missed call.

FaceTime picture quality is quite good, even when using less than ideal WiFi service (we ran tests while one side was on a hotel's free WiFi service). Audio can be muted using a button on the FaceTime display, and video can be paused (and will be paused) whenever you hit the Home button and visit another app. While you're away from the video call, you get the red "call in progress" bar across the top of the screen and your audio connection is maintained. Once you return to the FaceTime call, your video stream takes off from where you left.

This video pause not only prevents you from inadvertently maintaining a video link while you're not aware (there's no "now recording" green indicator light like the Mac iSight cameras), but also keeps your phone responsive while you do some other task, as it isn't having to handle video in the background. On the other end, there's no way to "share your desktop" like iChat, to show someone on the other end what you're doing on the screen (such reviewing your emails, or a tutorial for your mom on how to change settings on her phone) nor can you share a video feed of your photos or documents or anything like that. There's always FaceTime 2. And of course, you can also send documents via email or MMS to the recipient during your call.

You can also switch between the front facing VGA camera, which delivers a good-enough picture of you, and activate the rear facing camera to show off landscapes or crowds or your baby's footsteps to the caller on other end. The picture quality delivered by both cameras over FaceTime is about the same, even though the rear camera captures very high quality photos and full motion 30fps 720p HD video on its own.

Why Apple is opening FaceTime

FaceTime is so good that Apple's stated intention to open the specification up to other device makers appears surprising at first blush, especially to those stuck in the 90s mindset that open standards can't work and that proprietary control over software is the only way to make money. The reality however, is that Apple not only needs to get other makers to add support for FaceTime in order for its users to have people to video chat with, but also that if Apple didn't share its technology contributions (added to the existing IETF standards FaceTime is based upon), the rest of the world would likely stumble upon another one, which would likely be inferior or proprietary or both.

It might also be surprising that Apple isn't simply licensing its FaceTime technology to other makers as its own proprietary technology. The problem with introducing new proprietary software standards and trying to propagate them is that even if the vendor is successful (and that's not a given in a competitive landscape), it ends up owning a mess, and unable to freely compete as a vendor of that technology.

Microsoft discovered this reality with Windows, and is now unable to enter the hardware PC market. It again discovered this with Windows Mobile and again with PlaysForSure. When it introduced the Zune, it destroyed PlaysForSure. The company's new KIN phones are clearly hobbled both by being incompatible with and by competing against Windows Phone 7 and its Windows Mobile 6.x offerings.

A proprietary FaceTime system, licensed by Apple, would convert the company into the same early 90s beast that tried to license its Mac OS to cloners while competing against them with its own Macintosh hardware. That didn't work out. It would also put Apple in the position of Adobe and its Flash platform, which tries to bridge various computing platforms with a common denominator that can't do a good job of being both specialized/optimized and at the same time general purpose/good enough. The same kinds of problems haunt the future of the proprietary Skype protocol, and greatly limited Sun's Java on the desktop and JavaME on mobile devices.

The best way for Apple to compete as a hardware maker and as a mobile platform vendor is to freely offer FaceTime as an open standard just like those in place for the web (HTML5 and related technologies). By making the specification openly available, Apple can continue to work to sell the best implementation of FaceTime software and the best hardware for using it, and yet still work with partners who support it and competitors who bring compatible versions to market. That will also help prevent a rival, proprietary specification from gaining ground, creating a standards war where everyone (including Apple's customers) loses.

FaceTime is great new application of iPhone 4's new camera hardware, but it's not the only one. The next segment, part 3, will look at phone's new cameras and and how they perform both as still and video capture devices.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

Wesley Hilliard

Wesley Hilliard

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

William Gallagher

William Gallagher