Major weakness in Google's key storage breaks open Android's Full Disk Encryption

Higher end Android phones using premium Qualcomm chips have been seeking to court the attention of enterprise users, but new research shows that Android encryption is easy to defeat because the devices store their disk encryption keys in software, unlike Apple's iOS.

Android is as secure as wearing a robot costume on a skateboard

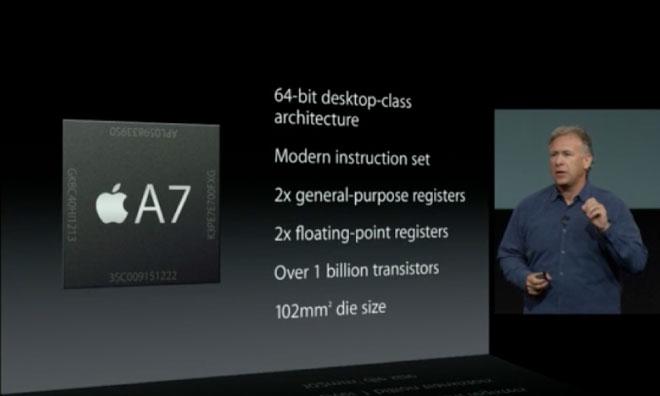

Apple's Secure Enclave

A report by Dan Goodin for Ars Technica cited research by Gal Beniamini which detailed "inherent issues" with Android's Full Disk Encryption that are "not simple to fix" and "might require hardware changes."

As detailed in Apple's iOS Security Guide, iOS devices store a Unique ID and encryption keys in the Secure Enclave, a specialized coprocessor internally developed as part of Apple's A7 and later Application Processors. As a result, Apple states that "iOS is a major leap forward in security for mobile devices." iOS is a major leap forward in security for mobile devices

Data held by the Secure Enclave can't even be read by the system; iOS runs on a separate processor and can only make simple requests to the Secure Enclave. This mechanism creates a strong barrier of protection around not only Full Disk Encryption, but also Touch ID, Apple Pay and other security related features in iOS.

Apple's conflict involving the FBI on device encryption involved an iPhone 5c, an older A6 model lacking the Secure Enclave and Touch ID. Even with that model, breaking device encryption required help from third party experts. New iPhones sold since 2013's iPhone 5s all use the Secure Enclave to enforce Full Disk Encryption and to authenticate users by fingerprint, without making biometric data or encryption keys accessible to iOS or to apps— or to any malware that a user might be fooled into installing.

Code to extract Android keys already public

Android devices depend on a series of partners to construct security policy. In "stark contrast" to iOS, Goodin noted that "Qualcomm-powered Android devices store the disk encryption keys in software. That leaves the keys vulnerable to a variety of attacks that can pull a key off a device."

A series of exploits related to vulnerabilities in the TrustZone security architecture used by Qualcomm's chips make it possible to run software within the TrustZone kernel, allowing attackers to steal keys and defeat Android's Full Disk Encryption and other security measures.

Google noted that it has since patched those vulnerabilities. However, Goodin noted that based on data compiled by Duo Security researchers, around 37 percent of affected Android phones can't be patched because the maker or carrier has not delivered the necessary patches (and likely will never).

Further, Beniamini (the researcher to detailed the issue) noted that many Android devices that have been patched (including Google's Nexus 6 that he tested, featuring an unlockable bootloader) can be rolled back to an older, vulnerable version of the software that makes the exploit possible again. For the enterprise, having more than a third of its Android devices wide open to broken encryption— and even more potentially exploitable with rollbacks— makes Google's platform unacceptable for deployment.

Android open to anyone who wants in

Android's architecture for storing its keys in software also opens the door for unanticipated new exploits from new vulnerabilities that haven't yet been made public. But it also allows phone manufacturers to crack open the encryption of their users— something Apple simply can not do to its own iPhone users, by design.

"Since the key is available to TrustZone," Goodin noted, "the hardware makers can simply create and sign a TrustZone image that extracts what are known as the keymaster keys. Those keys can then be flashed to the target device."

Goodin cited mobile security expert Dan Guido, the chief executive of Trail of Bits, as pointing out that "it's not just Google that can mess around with the software on your phone, but it's also [Google partners], and it's in a very significant way."

Benjamin described that Android's design "makes it possible for phone manufacturers to assist law enforcement agencies in unlocking an encrypted device."

It's noteworthy that Google's partners are regularly in conflict with the search giant over control of Android. And increasingly, Android partners are Chinese companies that operate in close partnership with the Communist Party running the People's Republic of China. That includes Huawei, now the second largest Android licensee after Samsung.

As The Information recently pointed out, Huawei "hasn't yet been able to strike a deal for a top U.S. wireless carrier to sell one of its flagship phones" because "the U.S. government forbids those same carriers from using Huawei telecom equipment due to fears of Chinese government snooping.""Google has always been behind on full disk encryption on Android. They have never been as good as the techniques that Apple and iOS have used" - security expert Dan Guido

Guido added, "Google has always been behind on full disk encryption on Android. They have never been as good as the techniques that Apple and iOS have used.

"They've put all their cards in this method based on TrustZone and based on the keymaster, and now it's come out how risky that is. It exposes a larger amount of attack surface. It involves a third party in the full disk encryption, and all this extra software that handles this key could potentially have bugs that allow an attacker to read it back out.

"Whereas on iOS it's very simple. It's just a chip. The chip is the Secure Enclave, and the Secure Enclave communicates via this thing they call the [interrupt-driven] mailbox. And that basically means you put really simple data in on one end, and you get really simple data out the other end. And there's not a lot else that you can do with it.

"These two approaches are completely different. [On iOS] there's no software to exploit to read the hardware key. On Android they expose the full-disk encryption key to a fairly complex piece of software this researcher has exploited."

In addition to Android phones powered by Qualcomm chips, Benjamin added that "he wouldn't be surprised if TrustZone implementations from chipmakers other than Qualcomm contain similar vulnerabilities."

TrustZone is a security platform licensed by ARM to Qualcomm and other chipmakers. It has been included on all ARM-licensed processors manufactured since 2012, which would include Samsung's Exynos chips.

Even most high-end Android phones turn Full Disk Encryption off

Most Android phones don't even turn on Full Disk Encryption because Google's implementation in Android doesn't rely on hardware accelerated encryption. That makes encryption so slow that most users who try it turn it back off just to have a usable phone. Last year, despite an initial effort to mandate Full Disk Encryption on higher end Android phones in Android 6, Google instead just relaxed its standards and told manufacturers to work toward the goal in the future.

A variety of Android benchmarks also turn off Full Disk Encryption when comparing Samsung's premium products to Apple's iPhone— which began using Full Disk Encryption on iPhone 3GS in 2009— because if they didn't Samsung's Galaxy scores would look much worse.

Android's lack of effective Full Disk Encryption certainly isn't the only security-related problem for Google's platform. In November, security researchers at Lookout noted the emergence of auto-rooting adware designed to survive even a "factory data reset" device wipe.

"For individuals, getting infected with Shedun, Shuanet and ShiftyBug might mean a trip to the store to buy a new phone," noted researcher Michael Bentley. "Because these pieces of adware root the device and install themselves as system applications, they become nearly impossible to remove, usually forcing victims to replace their device in order to regain normalcy."

In January, a new 0-Day kernel privilege escalation flaw that allows unprivileged apps to "gain nearly unfettered root access," including access to camera, microphone, GPS location and personal data, was discovered by Perception Point Research. It was found to have existed since 2012, long enough to have spread vulnerability across "66 percent of all Android devices."

Google has no way to patch those users. In fact, despite making the deployment of Android 6 Marshmallow a major priority over the last year, the new release only managed its way into a tenth of the installed base after a year.

This week, Kaspersky Lab also noted a new surge in ransomware— where attackers freeze users' phones and demand payment to unlock them again— among its Android users, citing136,532 mobile ransomeware infections in April, four times as many as the 35,413 it observed just a year ago.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Mike Wuerthele

Mike Wuerthele

Christine McKee

Christine McKee