Why Apple is now focusing on users, not units in Fiscal 2019

Across the last 20 years, Apple has shifted from selling Macs in a world dominated by Windows PCs to being a dominant global brand that services a vast installed base that's more valuable, influential, and lucrative than Windows was at its peak. Apple wants its investors to understand that, and is now challenging the media narrative that suggests it running an unsustainable race against various manufacturers churning out ever-increasing volumes of hardware units.

People over Units

Starting with Apple's Fiscal 2019 — which began this holiday quarter — the company will be reporting its hardware sales only in terms of revenue, rather than unit sales. As previous segments in this series have laid out, the cynical take that Apple is doing this in an attempt to hide failure is simply false.

Conversely, Apple's historical quarterly unit sales reporting has given analysts and pundits data that they frequently interpret incorrectly. In doing so, they obscure the company's actual performance and distract from its real value and potential.

Going forward, Apple's revenue-only reporting will still provide a clear picture of the overall health of each of its business segments — the same way that Microsoft, Samsung Electronics and other large companies with multiple lines of business report their quarterly performance without necessarily enumerating any units sold. The shift puts a new focus on what is really the most valuable aspect of Apple's global operations. Today, that's commonly understood to be iPhone sales. Just over a decade ago it was thought to be iPods, and prior to that it was assumed to be Macs.

The real value of Apple's business has never changed. The real reason why Apple has always been uniquely able to sell premium hardware in a marketplace full of less expensive, generic commodity is its ability to successfully reach people, convince them that things are better inside the Apple ecosystem, and then retain their loyalty by delivering what Apple's chief executive Tim Cook refers to as "user sat."

Essentially, Apple doesn't sell people units. It sells units of people on Apple.

Apple has successfully sold nearly a billion on Apple

Successfully selling and establishing a brand is much more work than simply selling units. But the work the company has invested over the last two decades has sold nearly a billion people on Apple. Industry research indicates that the installed base of customers Apple has built are largely not shopping around.

Apple's massive installed base represents an Elysium of buyers that consistently generate ongoing hardware, software, and services sales for Apple. It's also the premium demographic of consumer electronics buyers, necessitating Google to pay Apple billions for search traffic. Unit sales simply don't reflect the true nature of Apple's business.

Outside of Apple's installed base of users, there are a series of PC makers who collectively sell more computers than Apple. However, Windows PC buyers are not necessarily loyal to any specific PC maker, as reflected in the constant shift in sales share between them.

The situation is similar among Android licensees, where various companies take turns selling the most phones, but none have established any strength in creating the intensely loyal base of users Apple now has.

As Samsung has demonstrated, achieving years of large unit sales is meaningless if it doesn't generate sustainable income, particularly if those sales can subsequently be stolen away by lower-priced rivals. Samsung Mobile is now dragging the rest of the company down in profitability in part because it achieved unit sales without actually selling those buyers on Samsung.

Samsung buyers were simply sold Android as a commodity, and they left when they found it cheaper elsewhere.

The size of installed base "sold on Apple" is now so large that it acts independently of the industry. While overall sales of PCs, tablets, and phones are shrinking, Apple's Mac, iPad and iPhone have been bucking that trend.

Just as importantly, the price tiers Apple can offer are also rising upward in an environment where Windows and Android licensees are struggling to prevent their already low Average Selling Prices from dropping any further.

It's not simply that Apple is "raising its prices." Rather, it's expanding its offerings to include more luxurious products on the high-end, even as it now offers a $330 iPad and iPhone 7 starting at $450. What's new is that Apple's installed base is now so large that it can support a luxury tier that includes a $13,000 iMac Pro, a loaded iPad Pro at $1,900, and the high-end $1,450 iPhone XS Max.

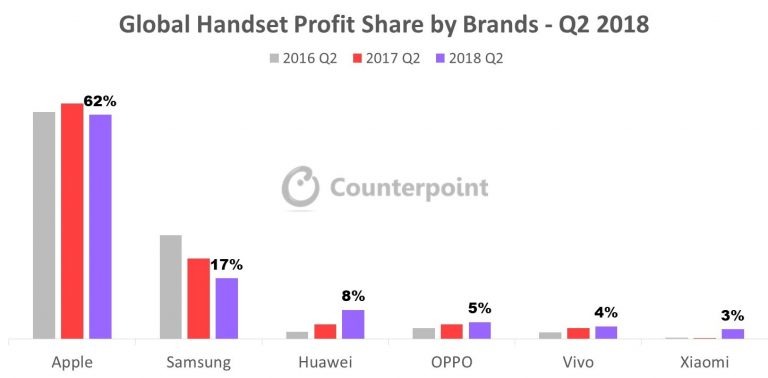

Samsung also offers luxury-priced devices, but it doesn't have an installed base that's large, loyal, and premium enough to actually sell commercially significant numbers of those devices. That results in large numbers of Samsung unit sales of smartphones, but at an Average Selling Price below $250, according to Counterpoint Research. Luxury brands in China have only pushed up their ASPs slightly higher, but are still at or below $275.

Meanwhile, iPhone ASPs are nearly $800 across sales of more than 200 million annually— that's a new development that analysts apparently still haven't yet digested. Samsung and its Android rivals in China are generating unit sales but not developing a reliable installed base of users. And because they can't sell higher-end devices in quantity, they can't bring down the cost of expensive components via economies of scale or generate the revenues and the profits that drive the development of future generations of technology on their own, without Apple's help.

Because this is a relatively new development— and unique in the tech industry— many analysts have no frame of reference to help them understand how Apple's business works, leaving them stuck in the mindset that Apple is still in its desperate 1990s struggle with cheaper commodity vendors over each unit sold.

The historical scrutiny of Macs units sold

Apple's critics love to talk about the potential of its demise, and nothing has suggested Apple's apparent, imminent death quite like the prospect of its products being "outsold" the same way Macs were outnumbered by the collective sales of Windows PCs, starting in the 1990s.

The Apple Computer of 25 years ago was negatively impacted by the rise of commodity Windows PCs for two reasons. First, Microsoft's large alternative PC platform attracted investment from developers that eroded away the level of interest in Macs and Apple's unique development APIs. This impaired Apple's ability to update or add value to its Mac platform, as many of the improvements it made were simply ignored by developers now focused on Windows, where more customers meant more money and a greater return on developers' investment.

Secondly, large volumes of PC sales created economies of scale for Intel x86 processors and PC-related standards such as PCI, Parallel and PS/2 peripherals, and VGA monitors. The economies of scale shared by PC vendors not only helped make Windows attractively cheaper, but also made the price of Macs appear less affordable because Apple lacked the hundreds of millions of PC users that were driving down component and peripheral prices via consistent, high volume sales.

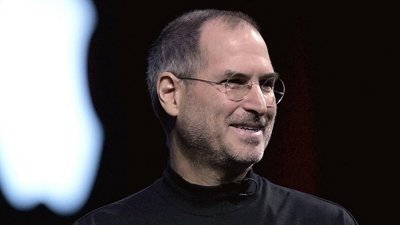

Steve Jobs worked to interrupt this vicious catch-22 by focusing Apple on fewer Mac models that could sell in higher quantities. Jobs also targeted areas where Apple could shine over commodity PCs, focusing on multimedia, education, ease of use, and the technical lead PowerPC briefly delivered during Intel's misstep with Pentium 4.

Even so, Apple under Jobs continued to struggle to sell more than a few million Macs annually in a market of hundreds of millions of PCs, forcing it to constantly work to identify new technical advantages it could exploit to stay ahead of generic PCs. Apple directed attention to its software, integration, and industrial design, ushering in the age of translucent colorful plastics and later more serious looking aluminum unibody designs which helped Macs stand out from generic PCs.

At the same time, Apple also worked to adopt Intel chips, USB, and other technologies that allowed it to share some of the economies of scale that were incrementally bringing down the component costs of PCs. The number of Mac units Apple was able to sell each quarter was a closely watched barometer of how well its various initiatives were working to win over PC user "switchers."

As noted earlier, Apple transparently documented this progress in incredible detail for years, breaking down its quarterly Mac sales by target audience, form factor (portables and desktops), and region sold. Yet over time it has increasingly published fewer details.

Apple's installed base gains a critical mass

Apple's dedicated installed base of Mac users have long appreciated the fact they were paying a premium for a superior experience. However, the Mac's price premium still prevented Apple from successfully attracting large numbers of PC users who had grown accustomed to saving money by putting up with the rougher edges of Microsoft's haphazardly managed Windows platform.

When iPod arrived, millions of new people were exposed to Apple's "far less frustrating" experience, where layers of complexity were purposely stripped away— not to demean the user's ability to figure out endless series of technical minutae, but to free them from having to waste time dealing with it. Jobs' iPod taught users to pay a premium for a premium experience. That lesson was more convincing in the individual world of everyday electronics, compared to the dauntingly complicated, technical patriarchy of desktop computing.

Seven years later, Apple went from selling 3 million Macs a year to annually selling 50 million iPods and 7 million Macs. But more importantly, Apple wasn't just increasing its unit sales — it was vastly increasing its installed base of loyal users. In 2008, the active Mac installed base had reached 36 million machines. That was still a small fraction of the PC market, but it represented a premium demographic of users capable of attracting some specialized attention from developers.

It was iPhone that really erected a walled garden of constrained experience for users, one that minimized the nature of personal computing so much that nobody thought of the new mobile computer as being a "computer" at all, but rather just an effortlessly simple device that could browse the web, listen to music, take pictures, play games, message friends and run a new class of spectacularly easy-to-use apps. In three years Apple was selling 50 million iPods, 40 million iPhones, and over 13 million Macs per year.

Apple's growing installed base begins crushing rivals' unit sales numbers

While the tech media obsessed itself with unit sales of iPhones — and initially smirked in contempt of its inability to execute Adobe Flash applets and regularly announced how much they hated that users were unable to compile their own kernel or side-load bootleg apps from random untrustworthy sources — none of that helped predict what was about to happen. It also didn't stop iPhone from blowing up into a force that completely destroyed every other existing smartphone platform of the day within just its first few years.

Giant established mobile phone makers Nokia, Blackberry, and of course Microsoft's Windows Mobile partners such as Samsung and Sony formerly had large unit sales. In fact, Nokia and Blackberry kept selling huge unit numbers of phones even as it became clear that they were completely outgunned and had no functional strategy for competing with iOS. Their unit sales collapsed suddenly and spectacularly, offering no real indication of health until it was too late to matter.

Apple's iPhone wasn't simply stealing unit numbers away from Nokia and Blackberry — it was building upon the installed base of its satisfied Mac and iPod users. Apple's installed base, not merely of machines but of users— was increasingly growing more important to understanding Apple's potential for success than just the unit sales it sold each quarter. While initially small, the unit sales of iPhones meant that Apple was attracting buyers into its retail stores, where it could sell them Macs and other products.

Apple's installed base begins creating its own weather

By 2010, Apple's installed base of users was large enough to be sold a new category of device. Apple adapted its iOS architecture to deliver the larger, tablet-sized iPad that year, which undercut the foundation of the conventional PC market and caused the entire Windows platform to tilt sideways as users flocked to Apple's dumb-simple device by the tens of millions every year for a period of time comparable to reign of Windows 95 through Windows XP.

The media narrative that insisted that Apple was just around the corner from once again being outnumbered by commodity was proven wrong over an extended period of time, first by iPhone, then by iPad. Additionally, unit sales of Macs were incrementally rising, but something else was also happening: its installed base was growing even faster. By 2013, Apple could announce that its installed base of Macs had doubled over five years, reaching 72 million.

The size of Apple's installed base was now capable of launching another new product category: Apple Watch, which inherited the sports-centric, wearable functionality of iPod, and added a fashion-oriented element of exchangeable bands and customizable faces. Its tight integration with Continuity, Health, Home, Siri and App Store titles helped it to grow within Apple's installed base of tech-hungry buyers even as Samsung's larger unit sales of Androids did virtually nothing to launch Galaxy Gear into a functional orbit.

Microsoft's once important Windows platform was similarly unable to drive sales of its cheaper Band, and despite its supposedly vast "leading" platform of Android, Google's Wear efforts have flopped as well.

Over the last year, Apple sold more than 217 million iPhones, 43 million iPads and 18 million Macs. Those are the last official unit sales numbers we're going to get. Apple also revealed this year that the Mac installed base had grown to 100 million.

That might sound small in comparison to iPhones, but this year Amazon was applauded for having 100 million Prime users. In a world of shrinking PC sales, Apple is not just bucking the trend in growing its unit sales but is expanding its core installed base of users.

Rather than understanding the integrated nature of Apple's businesses and how its product sales feed each other and launch new categories, many analysts and industry pundits have been distracted by focusing unit sales of specific categories. This is reflected in observations along the lines that Apple's non-iPhone businesses— Mac, iPad, Services and Other— are all so small compared to iPhone in units that they are a "rounding error" or "barely move the needle."

The reverse is actually true: Macs and iPad are collectively a $44.3 billion business, while Services and Other products generated over $37 billion and $17 billion respectively.

Rather than competing with iPhone for attention, Apple's base of iPhone users is driving business to its other segments— which are individually about the size of Amazon Web Services or Facebook! Conversely, the hardware segments of companies that don't have an iPhone business, like Google Pixel and Microsoft Surface (about $4.5 billion), are a fraction the size, if they can register at all.

It's a huge stretch to say that Google's search is driving Pixel at all, or that Windows, Office 360 or Azure are driving Surface.

Why a installed base of people is far more valuable than quarterly units sold

Apple no longer needs to desperately prove that it can entice PC users to switch to the Mac. Instead, it is increasingly leveraging its much greater installed base of iOS users to sell Macs. Beyond its 100 million Macs, Apple now has an installed base of users with 1.3 billion active devices. This installed base of users is more important than units sold for multiple reasons.

Firstly: for third party developers, the number of new Macs sold per quarter is far less interesting than Apple's growing, premium installed base of Mac users. The Mac installed base of users is both growing large enough to support new development and is also more likely to pay for software and services— certainly more so than users in Microsoft's PC platform who largely weren't even willing to pay to upgrade to Windows 10. Google's Chrome OS platform is not only tiny, but almost entirely made up of K12 schools looking for a nearly free solution.

If you combine Windows PCs and Chromebooks, various vendors' unit sales look more significant than they really are— particularly if you compare them against only Apple's Macs and segregate iPads into a separate category, as research firms like IDC do. But Apple's installed base of premium users tells an entirely different story, one that's actually true.

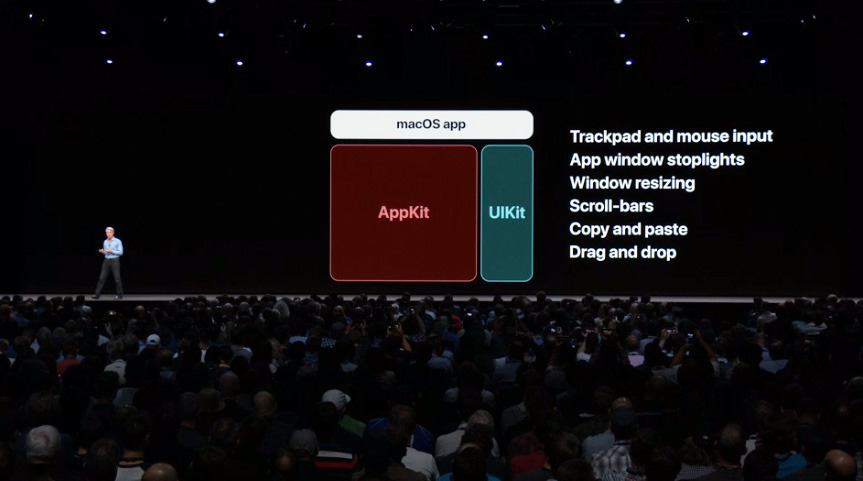

Secondly: the Continuity and familiarity between Macs and iOS are actually quite important, but goes missing when you break down Apple's installed base of devices into units of products. Further, the similarities in development and coding tools between Macs and iOS means that companies that have already invested in iOS because of its size and importance can repurpose much of what they already know to bring their software to the Mac.

Apple is making this even easier in its recent initiative to enable iOS UIKit apps to run on Macs— starting this year with its own internal iOS apps including Home, News and Stocks, and expanding next year to allow third parties to bring their iOS apps to the Mac App Store. The tight integration of Apple's huge installed base of users is not reflected in Mac unit sales alone.

Thirdly: the WinTel PC economies of scale that once worked against Apple have now virtually vanished. Instead, you can observe even more powerful economies of scale in Apple's internal development, where features created for the more than 1 billion iOS devices can be adapted to work across its 100 million Macs. This includes services like Maps, Siri, and News, which would have been impractical to build just for the Mac.

Apple's massive, highly profitable iOS mobile platform allows it to pay for other new technology investments that benefit Macs, including APFS and its custom T2 silicon with Apple's custom SSD controller, encryption, support for Hey Siri, and security for features like Touch Bar and Touch ID.

Looking just at unit sales of Macs, Apple's investment in macOS— creating a substantial new version each year, with a half dozen minor updates in between, along with related software, hardware, and firmware technologies used in Macs— barely makes any sense.

Other PC makers that maintain global unit sales of 20 million computers are largely shipping commodity hardware components packaged with Windows, with very little proprietary feature innovation. They can't afford to invest very much into their PC business. No PC makers have a massive, wildly profitable mobile device business that subsidizes development of new technology. And the declining nature of the conventional PC market means that Microsoft is increasingly less interested in driving investment in Windows development.

More importantly, in lacking a large, loyal installed base of users, generic PC makers can't count on anyone buying its new products, but must instead compete against other generic PCs almost entirely on price. That requires making value engineering design compromises that help differentiate Macs as premium machines.

The scarcity of high value, new unit growth

Next to Apple, large mobile device makers such as Samsung, Huawei, and Lenovo are barely making money on their mobile devices and all appear to be losing money on PC and tablet sales. None of this hardship is reflected in their high unit sales, which are increasingly unsustainable in a world where there is no more overall growth occurring in PCs, tablets or even phones.

Huge potential expansions of volume shipments into new regions are growing scarce. And the growth that is occurring is happening in emerging countries where already slim margins are being pared down even further by cutthroat pricing competition among device makers. While Apple has some near-term hurdles to jump in markets like India, its long-term strategy is maintaining iOS as an aspirational brand, so that once there's an installed base of smartphone users, it can upgrade them to iOS the same way it upgraded Americans from Windows Phone and later Android; Japan and Europe from Symbian; and China from Linux and Android.

All of those territories were once sold huge unit sales volumes of non-iPhones for years before Apple entered and began selling them iPhones, and then sold its iPhone users on iPad and Macs, and then Apple Watch, and increasingly apps, subscriptions, and other Services.

Functional business model vs failures

It will be much easier for Apple to upgrade the world to higher-end gear than it will be for the collective commodity licensees of Windows and Android to find new markets to sell more units.

In part, that's because Apple has a functional business model for increasing the desirability of its products in a crowded field. For the last twenty years, Apple has consistently been selling hardware at a profit that can fund investment in new technology. And rather than that model wearing out as a strategy, it is working increasingly better over time, launching new categories of products and enhancing the lives of Apple's base in a way that retains their loyalty. The base is growing substantially and the price they are willing to pay keeps increasing.

Alternatively, commodity hardware producers have been locked in a vicious cycle of lower prices and even cheaper competition that is driving them out of business. Slim margins aren't enabling them to invest in technology, and like Apple in the 1990s they are locked out of the economies of scale that the most valuable mobile platform is driving.

The standouts that are seeking to copy Apple's model, including the Microsoft Surface, Google Pixel, and Samsung Galaxy brands, are spending billions on product development that isn't resulting in high volume sales or sustainable profits; instead, they're merely burning up resources generated elsewhere by those companies. As Zune, Windows Phone, Nexus phones, Chromebook Pixel, and Galaxy Player all demonstrated, unsustainable sales volumes will eventually result in failure, despite many assurances that these companies are invested in a long-term approach.

That raises the question: what is preventing other companies from copying Apple's success in building a thriving installed base of loyal, premium users? The next segment in this series will examine why.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Wesley Hilliard

Wesley Hilliard

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

Amber Neely

Amber Neely