Editorial: Apple's Ax SoC move from Samsung to TSMC can't happen fast enough

Apple's voracious appetite for powerful, efficient new chips to power its iOS devices, complicated by the tense relationship with its current supplier Samsung, is sparking a construction boom for Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co. But why has it taken so long?

Apple's partnership with TSMC to produce new generations of its Ax line of ARM-based chips has long been understood to be at the core of the iPhone maker's plan to shift its component sourcing away from Samsung.

But Apple's very public problems with Samsung started back in 2010, and have continued through many months of negotiations and finally a series of extended court cases that have, so far, only reached the earliest stages of patent infringement findings.

Why does Apple still do business with Samsung after so many years of failed negotiations, bitter protracted trials and a series of massive ad campaigns where Samsung has both ridiculed Apple and its lined-up customers while at the same time claiming ownership of delivering the next "one more thing" that people might want to queue up to get?

To understand, one needs only look at the timing and scope of work required to plan, build and equip the massive chip fabrication plants necessary to make the switch away from Samsung. If moving Ax chip production to a new fab were easy, Apple would have already done it, just as it has moved to new component suppliers for parts including RAM and display screen.

Apple's Samsung Ax plans were put into place years in advance

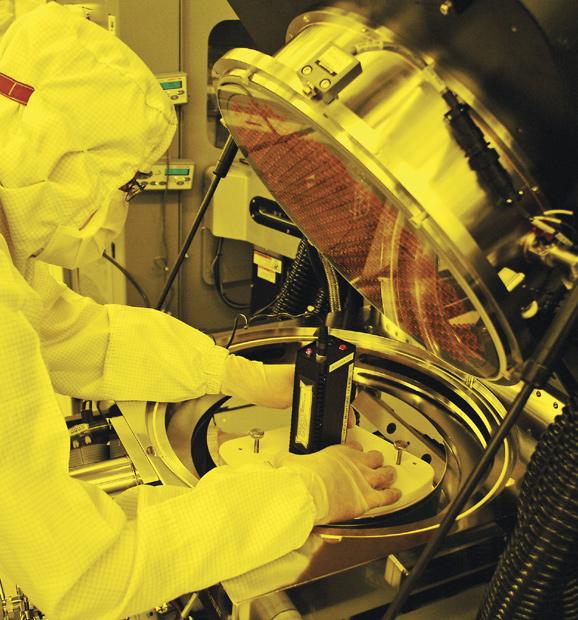

While many of the details of Apple's chip partners remain secret for competitive reasons, it is known that in 2010, Samsung announced plans to spend $3.6 billion to expand chip production in Austin, Texas, resulting in the new S2 facility building 300mm silicon wafers in a 45nm logic process.

By October 2011, five months after producing its first silicon test wafers, the S2 plant was reported to have reached its intended capacity, churning out 40,000 wafers per month that could be cut into individual A4, A5 and A5X chips for use in mobile devices like the iPhone and iPad.

Production at the Austin S2 plant was coordinated with Samsung's S1 facility in Giheung, South Korea; S2 was reportedly dedicated exclusively to serving Apple's demand for chips, and Apple continues to be Samsung's largest customer.

This means that the chip supply for last year's iPads (including the A5X powered "new iPad") entered its advanced planning stages in 2010. To meet the incredible demand for tens of millions of iPads and additional tens of millions of iPhones, iPod touches and Apple TVs, Apple has needed to line up its supply chain years in advance.

Going forward, successive generations of Apple's Ax chips are going to be even more advanced, even as demand for Apple's mobile devices increases. This makes the task of sourcing an affordable supply of these parts increasingly difficult. Building more powerful chips using a smaller, more efficient process requires retooling facilities even as supply constraints demand the construction of newer, larger and more productive fabs.

Piloting the maiden flight of iOS, through lightning and gunfire

Apple's task of keeping up with the global demand for iOS devices (orchestrating the production of increasingly sophisticated chips in dramatically larger quantities) would be difficult enough if it were teamed up with a reliable components partner.

Instead, the company found itself under attack by Samsung, not only from the Galaxy smartphones cloned from Apple's own designs but also in the courts, where Samsung was demanding that Apple's devices be taken off the shelf due to dozens of patent claims related to industry standards such as 3G and WiFi technologies. So far, Samsung has lost or withdrawn every one of these claims. Defending itself from these retaliatory challenges, however, has kept Apple's executives taxed as they attempt to focus on their own goals.

At the same time, Samsung was spending record billions to saturate the airways with ads mocking iPhone users and depicting itself as the only true innovator, a message even the tech industry began regurgitating right up until Samsung unveiled its Galaxy S4 with underwhelming features that failed to dazzle the audiences it had prepared for Broadway-class showmanship.

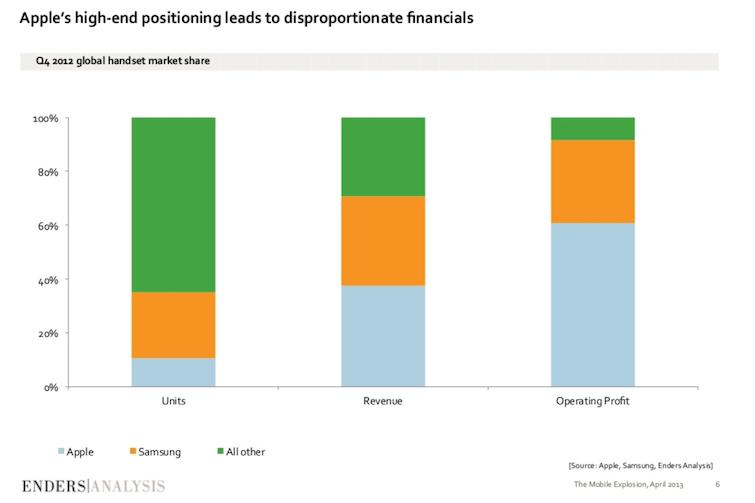

Samsung's record billions of dollars in advertising and promotion had even convinced the tech media that Apple had at some point become the largest producer of phones in the world, and that Samsung was a scrappy underdog heroically fighting to stop the iPhone from tyrannizing Chinese workers and monopolizing the smartphone business.

This lead to reporters agreeing with each other that Samsung had recently "won back the lead" in phone sales from Apple. In reality, while Apple's iPhone rapidly became the most popular smartphone model in many global markets, Apple has never dominated the mobile industry in unit sales, not by a long shot. Apple has only ever led the mobile industry in profits and in the acrimonious critical scorn of pundits.

No other product ramp in the history of technology has been so maligned, browbeaten, slandered and falsely accused than Apple's iOS platform. From incredulous competitors who insisted at its unveiling that it was simply a hoax to analysts who spread stories that the original iPhone's new screen would suddenly decay after a few months, every successive model of iPhone and iPad has been viciously attacked as flawed, incompetent and the likely subject of a massive recall prior to each achieving record sales: from supposedly failing Infineon 3G chips in the iPhone 3GS to iPhone 4's AntennaGate to scathing criticism of iPhone 4S's Siri and iPhone 5's Maps.

On top of that, groups like Greenpeace misleadingly attacked Apple's leadership in environmentally sustainable manufacturing and operations, while major news outlets followed a one man show supposedly depicting the company's callous indifference to human rights and worker exploitation, two areas where Apple had long been working to improve things not only among its own suppliers, but in setting an example for its competitors to follow.

If the history of Apple's iPhone were accurately captured in a film, audiences would likely find the story completely unbelievable and simply walk out of the theater. And yet, as things play out in the real world, despite the company now accounting for the majority of profits in both the PC and mobile industries, the market has plunged Apple's valuation to 52-week lows in apparent anticipation that its stricken competitors might reanimate themselves and start actually competing with the company.

This is the context Apple has faced while working to transition its chip supply from Samsung to a new fab that doesn't threaten to use its own investments in production against it as a competitor.

Justice delayed is competition demanded

Any efforts to make changes to its complex, delicate supply chain, particularly in the realm of sourcing its customized Ax chips, would take years to plan and require billions of dollars to execute. While lawyers from Apple and Samsung argued their positions in court over many months, Apple's executive team wasn't willing to bet that the courts would resolve matters satisfactorily.

Apple's plan B for its Ax chips was further complicated by the fact that there are a very limited number of fabs on earth with the capacity and technology to build the parts the company needs next year and the year after that. Chip fabs are so expensive to maintain that they simply can't afford to sit around with idle capacity, waiting for customers. Finding a new Samsung was not going to be easy.

The global economic slowdown Apple was coping with as it rolled out successive generations of the iPhone was having an even stronger impact on his competitors. While Apple's own sales resisted the predicted effects of "global macroeconomic conditions," which many analysts had insisted would throw it off course, slack projections of sales for other electronics producers had slowed the global expansion of chip production facilities.

While Apple continued to coordinate work with Samsung in 2011 to produce the sophisticated new A6 at the fab's newer, 32nm logic process for last year's iPhone 5, along with an even more sophisticated A6X version for the iPad 4, it was also busy working to line up the production and supply of a successive generation of new 28nm chips. But not with Samsung.

Instead, Apple turned to TSMC, a fab with the technology to pull off the next Ax chip but lacking Samsung's competitive arms in smartphones and other electronics.

TSMC had already produced iPhone and iPad chips as the foundry for Broadcom, CSR, Cirrus Logic and Qualcomm, but speculative rumors that the fab might take over production of Apple's Ax SoCs first started in early 2011.

Apple was said to be booking rush orders to test TSMC's ability to produce reliable yields and quantities of its existing chip designs throughout the year, and by September 2011, it was reported that Apple had actually signed TSMC on to produce its future chips.

How fast can you build a fab?

"How long does it take to go from a muddy field to full 28nm capacity?" asked Paul McLellan in an article on SemiWiki.

McLellan noted that TMSC's vice president of operations outlined that company's ramp to production of 28nm chips "was the fastest TSMC has ever done," with the firm's build out being accelerated from one new fab construction phase per year to three phases being orchestrated in parallel each year.

The company's first 28nm fab "was a muddy field in Taichung" in the summer of 2010. One year later, the building and its clean rooms were completed in phase 1. Another ten months were spent installing and qualifying equipment in phase 2. By the winter quarter of 2012, the fab had ramped up to a production speed of 50,000 wafers per month.

Next month, the fab will begin a new phase that will double its production to 100,000 wafers per month. Apple reportedly wanted to buy all of TMSC's production capacity, but will have to settle for as much as it can afford.

TSMC's capacity to ship 28nm parts was reportedly strained because its existing customers, spooked by the recession, initially reported a major drop in their component needs. However, demand has actually turned out to be much greater than they forecast, resulting in subsequent insufficient manufacturing capacity and a constrained supply for everyone.

Fortunately for Apple, it's making three quarters of the mobile industry's profits, enabling it to plan and build for its capacity needs. Going forward, TMSC plans to move to even smaller 20 and 16nm fab processes even faster, and is also working toward production of larger yielding, 450mm wafers.

In addition to its fabs in Taiwan, TSMC is also believed to be the company behind what is known as "Project Azalea," a mysterious American development thought to be a chip manufacturing facility connected to Apple.

Again, the efforts to build, equip and ramp up production at new fabs takes years to complete. This indicates that once Apple completes its transition to TSMC, it will enjoy a relief period where it can redirect the energy currently being lost in its tense relationship with Samsung and its efforts to transition its business elsewhere, and refocus those efforts on rapidly scaling the sophistication and efficiency of new Ax chips.

Once its investments in new chip production begin to bear fruit, Apple appears poised to drive a huge leap in ARM-based chips, which will begin to occur just as the conventional x86 PC market reaches its lowest, weakest point ever. No wonder the company is spending billions to proceed with its fab plans at a blistering pace.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

William Gallagher and Mike Wuerthele

William Gallagher and Mike Wuerthele

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic