Stanford researchers develop method for tracking mobile devices using battery charge data

Privacy advocates have long tried to educate consumers on the perils of giving apps access to GPS data, but a group of Stanford researchers has developed a method to infer a device's location from a seemingly much more innocuous source — battery charge information.

The attack — which its creators have dubbed "PowerSpy" — relies on the fact that mobile devices use more power as they get farther from connected cellular towers. By comparing the pattern of battery consumption on a device to a known pattern established by previously measuring a given area, the location can be determined without access to any other location information.

This is similar to how song identification apps like Shazam operate — thousands of audio "fingerprints" are created and stored in a database, and new snippets recorded by users are themselves fingerprinted and compared to the existing set.

"We show that by simply reading the phone's aggregate power consumption over a period of a few minutes an application can learn information about the user's location," researchers Yan Michalevsky, Dan Boneh and Aaron Schulman of Stanford wrote in their paper, published earlier this month. It was co-authored by Gabi Nakibly of Israeli defense company Rafael Ltd.

"Aggregate phone power consumption data is extremely noisy due to the multitude of components and applications simultaneously consuming power. Nevertheless, we show that by using machine learning techniques, the phone's location can be inferred."

While the researchers achieved impressive precision in tracking known routes, they were also able to infer longer routes by analyzing data collated from a variety of shorter routes. They give the example of tracking movements on a college campus:

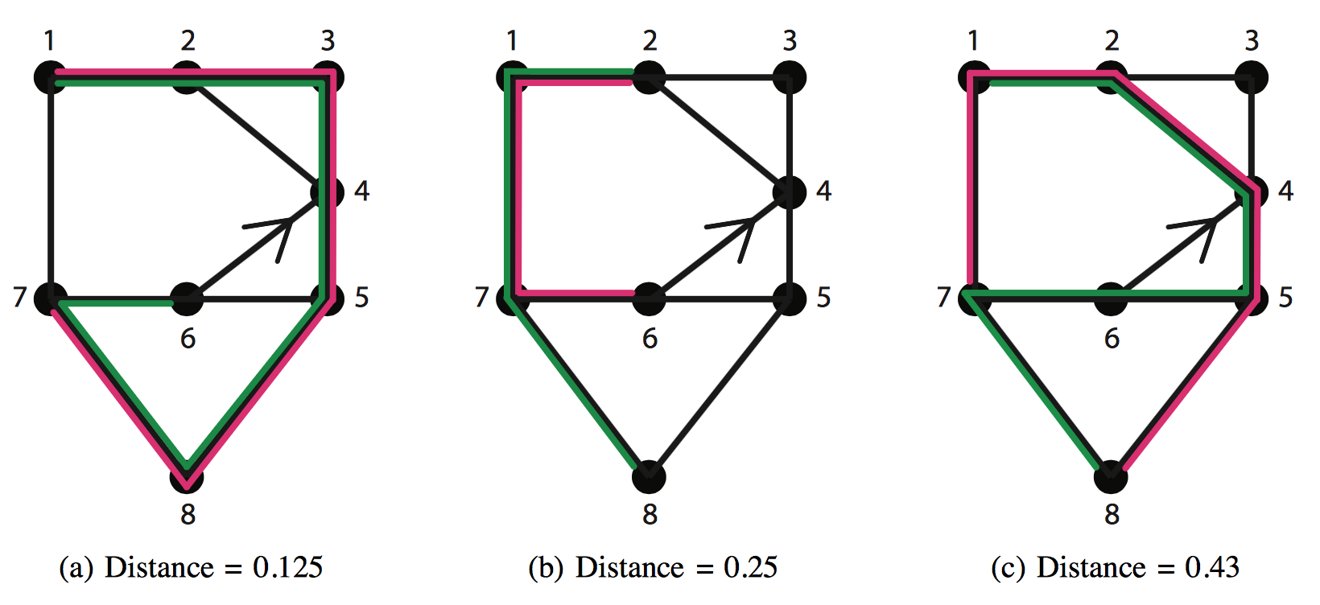

"We address this problem by pre-recording the power profiles of all the road segments within the given area. Each possible route a mobile device may take is a concatenation of some subset of these road segments. Given a power profile of the tracked device, we will reconstruct the unknown route using the reference power profiles corresponding to the road segments."

Though the research was performed on Android devices, there does not appear to be any reason the same method could not work to locate devices running Apple's iOS or other mobile operating systems, as long as battery charge data is available. The team also notes that the availability of battery data via the HTML5 Battery API could increase the risk of on-the-sly tracking by only requiring that the user load a web page.

To mitigate the issue, the researchers suggest remedies like removing the radio stack from power consumption reporting or requiring superuser privileges to access the data. Alternatively, OS makers could treat battery data as a location indicator, giving it a spot in the users' privacy preferences.

"The user will then be aware, when installing applications that access voltage and current data, of the application's potential capabilities, and the risk potentially posed to her privacy," the team wrote. "This defense may actually be the most consistent with the current security policies of smartphone operating systems like Android and iOS, and their current permission schemes."

Sam Oliver

Sam Oliver

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Andrew O'Hara

Andrew O'Hara

Sponsored Content

Sponsored Content