Apple has made significant changes to Safari in Mac OS X 10.5 Leopard, introducing integration with Dashboard, smart drag and drop of tabbed windows, full text searching of your web history, and more. Here's a look at the birth and maturity of the online web browser, as well as a look at what's new in Safari 3.0.

This report goes to great lengths to explore the origins, history, and maturity of the web browser. For those readers with limited time or who are only interested in what's due in Leopard, you can skip to page 3 of this report.

Safari's Origins

The World Wide Web itself got started on NeXTSTEP, but the ideas behind delivering hyperlinked documents with scripted behavior went mainstream several years before the development of the web as an Internet service in 1990.

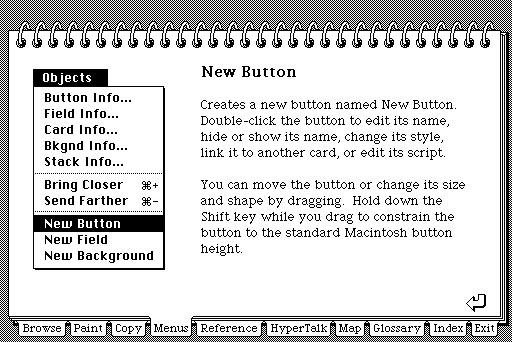

The first mainstream application for developing and using hyperlinked text and media was Apple's 1987 HyperCard for the Macintosh (above). The system worked like the forms designer of a graphical database or a rapid application development system. Standalone collections of hyperlinked cards called Stacks were powered by HyperTalk, a scripting language designed to be approachable by non-technical users.

Bill Atkinson, who had worked on HyperCard at Apple since 1985, assigned the rights to the application to Apple under the condition that the company would bundle it for free on all new Macs. That ended up making HyperCard popular with Mac users but didn't do anything to impress Apple executives, who ended up marginalizing its continued development until it eventually fell into obsolescence.

HyperCard was spun off into the Claris software subsidiary. Plans to merge HyperCard into QuickTime as a scripted interactivity layer called QuickTime Interactive began in the mid 90s, but it was never completed. The remains of HyperCard as a product were eventually abandoned, along with QTi, during Steve Jobs' housecleaning purge that followed Apple's acquisition of NeXT in 1996.

Inspired by HyperCard

The legacy of HyperCard lived on, however. Apple turned its HyperTalk scripting language into the Mac's system wide AppleScript architecture for building scriptable actions within applications, workflows in Automator, or even full blown programs using AppleScript Studio -- now a part of Xcode. HyperCard also helped inspire a series of projects to deliver visual application development, hyperlinked media, and scripted presentation environments, including:

- NeXT's 1988 Interface Builder for graphical, rapid application development.

- Microsoft's 1991 Visual Basic development environment.

- Netscape's 1995 JavaScript for the web.

HyperCard also helped to ignite the development of the web itself, both directly and indirectly.

Weaving the Web

The world's first web browser, called WorldWideWeb, appeared in 1990. Developed by Tim Berners-Lee at CERN using NeXTSTEP (above), it served as the client software for a new www Internet service, which defined HTTP, the HyperText Transmission Protocol, as a way to deliver linked hypertext documents from www servers hosting pages to the www browsers requesting them by URL address.

Â

Steve Jobs' NeXT computer was central to the development of the the web largely because it offered uniquely advanced rapid development tools, but also because NeXT occupied a niche in higher education and advanced computing, and provided full support for the open Internet at a time when PCs were just beginning to use local area networks.

Viola: HyperCard for X Window

At the same time, Pei-Yuan Wei at UC Berkeley began work on Viola, a project to bring the features of HyperCard to Unix terminals running X Window. "I got a HyperCard manual and looked at it and just basically took the concepts and implemented them in [X Window for Unix]," Wei later explained.

Â

Wei intended to adapt Viola to use the Internet to distribute its hypermedia documents, but then happened upon the work already done by Berners-Lee on NeXT. Adopting the HTTP architecture of Berners-Lee's www service resulted in the creation of the ViolaWWW web browser for X Window systems in 1992 (below).

NCSA Mosaic

Authored and advocated by US Senator Al Gore, the High Performance Computing and Communication Act of 1991 funded the development of the National Center for Supercomputing Applications' High-Performance Computing and Communications Initiative, which included development of the Mosaic web browser (below).

NCSA's Mosaic browser could be freely downloaded for non-commercial use and was rapidly made available to consumer operating systems, including the Amiga, the Mac, and Windows. While modeled after earlier browsers, including ViolaWWW, Mosaic's support for popular computing platforms, its ability to view graphics inline within web pages, and its focus on being easy to use for non-technical users all worked to rapidly make it the most popular web browser in the early 90s among the small population actually using the web.

Â

Netscape Navigator

Marc Andreessen, who led the NCSA's Mosaic browser development as a student at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, graduated in 1993 and went on to found Mosaic Communications, later renamed Netscape, with the goal of delivering the commercial Netscape Navigator web browser. Andreessen partnered with Jim Clark, who a decade earlier had graduated from Stanford University in California to start up Silicon Graphics. Armed with his experience at SGI, Clark helped Andreessen develop a business plan for continuing the development of the Navigator browser.

Â

Since there were already other free browsers available, including Mosaic, Netscape decided to give away its web browser client and planned to make money selling web server software. Netscape's initial rapid innovation and its adoption of Mosaic's policy of being free for non-commercial use quickly made its browser the new standard for web users.

On page 2 of 3: Microsoft Discovers the Internet; Netscape Crashes; Apple's CyberDog; Netscape's Mozilla Burns to the Ground; Firefox Rises from the Ashes of Netscape; and Mozilla Pattered After Apache.

Â

Microsoft Discovers the Internet

Leading up to the delayed release of Windows 1995, Microsoft was pushing hard to roll out its new MSN online service as an AOL killer. While some within the company--particularly J. Allard--urged the adoption of the web and Internet standards, MSN manager Russell Siegelman decided to instead to focus on MSN as a proprietary alternative to AOL that did one thing AOL didn't: ship bundled with Windows.

AOL had to cover the planet with free diskettes with its online software; Microsoft planned to simply dump its own online software on the Windows 95 desktop and grab the entire online services market for itself. It was too late to shake down AOL however. The real movement online was in the open web. As Microsoft discovered this in mid 1995, it rapidly turned its online strategy around.

Microsoft licensed web browser technology from Spyglass--a parallel commercial spinoff of the NCSA Mosaic project--to develop Internet Explorer as its own browser in order to destroy Netscape as a threat. Microsoft invested significant resources into IE, outpacing Netscape both in development and marketing. It not only bundled IE with Windows--in violation of its earlier consent decree--but also used its marketing clout to push dialup ISPs to distribute IE instead of Netscape.

Netscape Crashes

Just like Microsoft, Netscape's strategy was to lock up the browser market and tie web development to its own non-standard extensions to HTML, in order to push the adoption of its own web server software. That resulted in a product that was really no better for consumers and businesses than Microsoft's IE.

Starting in 1997, Netscape's ongoing development plans began falling apart. Its engineers were conflicted about whether to continue development of the top-heavy and increasingly problematic Mariner code-base used through Navigator 4, or to start over with an entirely re-architected new web rendering engine named Gecko.

Netscape ended up doing both. First, Navigator 4 was replaced with a suite of products called Communicator 4, which tacked on an email client, a newsgroup reader, an address book, calendar, collaboration tools, a push client, and an HTML editor. Netscape's aging, bloated browser was now plagued with a series of marginal companion products that nobody really wanted. Communicator was trying to compete with Microsoft by becoming the user's entire desktop.

Apple's CyberDog

After a brief fling with AOL to create a parallel online universe called eWorld between 1992 and 1994, Apple discovered the web too, and delivered Cyberdog (below), a suite of Internet tools -- a web browser, ftp client, news, and email services -- built as OpenDoc application components.

Cyberdog was largely a demonstration of the potential of OpenDoc. As such, it demonstrated that OpenDoc was a solution to a problem that did not really exist. Nobody wanted to assemble components; they wanted regular apps. While CyberDog promised to replace the monolithic, bloated code in suites like Netscape's Communicator with smaller, faster components, the system had to load support libraries that effectively erased any intended benefits, ending up slower and fatter that what it hoped to replace.

As a strategic battlefield in the war between Netscape and Microsoft, Apple had the luxury of not really needing to develop its own browser for the Mac. As noted in Mac Office, $150 Million, and the Story Nobody Covered, Microsoft used the threat of delaying Office for the Mac to sign a 1997 deal with Apple to force Netscape off the Mac desktop and therefore handicap Netscape's efforts to provide a cross-platform browser.

After rapidly gaining web browser market share in 1997 as the default Windows browser, Microsoft introduced a variety of initiatives to tie all web-based development to Windows and proprietary features of IE. Microsoft similarly worked to link Java development to Windows and the IE browser, killing interoperability for both Java and the web, effectively nullifying both as cross platform alternatives to Windows-centric development.

Netscape's Mozilla Burns to the Ground

In 1998, Netscape dropped its original plans to deliver Netscape 5 as significant revision to Communicator 4. Instead, it chose to freeze development of the classic Mariner engine and instead launch a new open source project called Mozilla to deliver the new Gecko rendering engine as an open source project. That ended up taking much longer than originally anticipated.

Â

In 1999, AOL paid $4.2 billion for Netscape, hoping to use its new browser as a platform for modernizing the AOL service from a proprietary system of custom content to a web-based one. That business plan was complicated by the problematic ongoing development of the new Gecko-based browser. Desperate for results, AOL pressed the Netscape team to ship Mozilla's beta code as Netscape 6 in 2000, resulting in public embarrassment and further associating the Netscape brand with incompetence.

In comparison, Microsoft delivered progressive new releases of IE in 1997, 1999, and 2001 (below), leapfrogging Netscape in innovative new browser features. Netscape only gave consumers and business users a choice between an old, buggy, and slow Communicator 4 and the unfinished, buggy, and slow Netscape 6.

Microsoft quickly took over the entire browser market, both on Windows and on the Mac. With no further need to compete or innovate, Microsoft subsequently dropped IE for the Mac platform and did not release another major revision on Windows until late 2006, five years later.

Firefox Rises from the Ashes of Netscape

In 2003, AOL decided to shut down the remains of Netscape entirely. Since the Mozilla Organization was mostly made up of Netscape employees, Mozilla as a project had to quickly learn to swim or die trying.

Â

Much like Apple in 1997, Mozilla in 2003 had to jettison its grandiose -- yet ultimately deadweight -- architectural fantasies and get busy developing and delivering products real people might actually want to use. Mozilla's Gecko rendering engine rose from the Netscape ashes under the name Phoenix, then Firebird, then Firefox in a series of squabbles over the project's name.

Â

Once that was sorted out, Mozilla developers began copying the success of the original Netscape browser from a decade prior by releasing regular, innovative, and free updates to Firefox.

Mozilla Pattered After Apache

The popular Apache web server had also descended from the NCSA Mosaic server, although instead of becoming a commercial spinoff like Netscape or Spyglass, it became an open source project curated by the Apache Software Foundation. Unlike Netscape, Apache's dominant position in web servers was never overtaken by Microsoft.

Â

After AOL pulled the plug on the Mozilla Organization by laying off or reassigning all of Netscape's remaining employees in 2003, Mozilla reorganized as the non-profit Mozilla Foundation, much like Apache had. In 2005, this foundation set up the Mozilla Corporation as a wholly-owned subsidiary to allow it to earn revenue on commercial partnerships. Mozilla is now supported almost exclusively by its contracts with search engines.

Â

The Firefox browser is primarily aligned with Google, which pays Mozilla for the default direction of search engine requests to its servers. Around 95% of the $52.9 million in combined revenues of the Mozilla Foundation and Mozilla Corporation come from search engine agreements. Firefox has grabbed back a steady increase in market share, and currently has about 15% of the browser market. That consistent growth forced Microsoft to respond with the release of Internet Explorer 7 in 2006, after five years of no new major updates to its browser.

On page 3 of 3: Apple Launches Safari; and Safari 3.0 on Leopard.

Â

Apple Launches Safari

After being left for three years with a stagnant version of Microsoft's Internet Explorer on the Mac, Apple announced the public beta release of its own new web browser at the January 2003 Macworld Expo. While many expected Apple to release a customized browser based upon Mozilla's Gecko engine, Apple instead chose to base its browser upon KHTML, the engine powering KDE's Konquerer browser.

Â

This is particularly interesting because Apple had hired Dave Hyatt in 2002, who had been working for Netscape since 1997. Hyatt created the Camino browser and was a co-creator of Firefox, both of which were based on Gecko. By the time Apple began work on Safari in 2002, Mozilla had a few years of development effort invested in its new Gecko engine. However, KDE had invested a similar amount of time in its own KHTML browser engine, which began in 2000. KDE's engine was faster, smaller, and offered better support for web standards.

Â

Rather than using Gecko, Apple chose to enhance the KHTML rendering engine, replacing its dependancies on the Qt toolkit with an adapter that wrapped the engine with a Cocoa friendly Objective-C API. That enabled Apple to preserve as much portability and commonality with KHTML as possible. The result was the open source WebCore library. Paired with Apple's JavaScriptCore, similarly based on KDE's kjs JavaScript engine, the entire package is called WebKit. That framework is used by a number of Mac applications to render HTML content, including Safari.

Â

Safari adds user interface features to WebKit in the same way Firefox adds a user interface to the Mozilla Gecko engine. Like Mozilla, Apple earns some revenue from partnerships with Google. However, the main reason for developing its own browser has been to ensure the Mac platform isn't left with a second class web browser.

Safari 1.0 (below) introduced innovative bookmark organization and featured a slim user interface profile to show-off the web content being displayed rather than the browser's own buttons.

Safari 2.0, released with Mac OS X 10.4 Tiger, was commonly called Safari RSS in Apple's marketing to feature its built in support for parsing syndicated RSS feeds (below). It also supported a private browsing mode, parental controls, and saving website content locally as a web archive. Safari had also advanced in its support for web standards and in rendering speed in a series of regular update releases.

Apple released Safari 3.0 (below) in June as part of the WWDC private release of Leopard, but also as a public beta for users of Mac OS 10.4 Tiger. Apple also offered a version for Windows XP and Windows Vista in an effort to spread the adoption of its Safari browser and make it easier for web developers to perform cross platform compatibility testing.

The new version of Safari featured improved searching within web pages, the resizing of text input fields within a page, drag and drop tabs, and the ability to save a group of tabs as a single bookmark. Apple also touts major speed improvements, claiming page rendering that's up to twice as fast as Internet Explorer 7, and JavaScript performance that is up to 2.8 times as fast as IE 7.

Safari 3.0 on Leopard

Running on Leopard, Safari loses the brushed metal frame it has always had, and adopts the standard unified appearance of other Leopard apps. On Windows, Safari is already there, although its close box is strangely on the wrong end of window's title bar.

Safari in Leopard also has a new feature called Web Clip. Click the scissor toolbar icon, and Web Clip allows you to select an area of a web page as a web clipping widget for use in Dashboard. The selection arrow turns into a box that locks onto specific regions of the page in the same way the iPhone's Safari identifies areas for zooming in when its display is double tapped. You can also create a freeform box that can cut out any arbitrary section of a web page.

Once selected, the region becomes a live widget in Dashboard that works identically to loading the full page a Safari window. Clippings can be assigned a custom frame design, and you can load any number of clippings into the Dashboard.

The new Safari can also purge history items at a set schedule, either every day, week, two weeks, a month, annually, or manually. Like other Leopard-savvy apps, it also defaults to directing downloads to the new Downloads users folder, and those files are tagged with the date and time they were downloaded. When you open them, the Finder warns you that the file was downloaded from the Internet, and tells you when, flagging any potential malware as suspicious.

Leopard also indexes a full text content search of bookmarked web pages and history items, so when you search through your history or bookmarks looking for information on a previously viewed page, you don't have to recall the website, the page title, or anything in URL; you can simply search for the word you are after.

While the rest of Mac OS X Leopard doesn't come out for another eight days, you can download Safari 3 now for free, both for Mac OS X Tiger and for Windows.

Check out earlier installments from AppleInsider's ongoing Road to Leopard Series: iCal 3.0, iChat 4.0, Mail 3.0, Time Machine; Spaces, Dock 1.6, Finder 10.5, Dictionary 2.0, and Preview 4.0.