The Mac is not a single computer but a lineup of models spanning laptops and desktops. It has been the center of Apple's successes for generations — from the first one released in 1984 to the one that saved the company from bankruptcy in 1998. Today, Apple's Mac lineup is used to develop apps for all of its platforms and remains essential to the ecosystem.

The transition to Apple Silicon breathed new life into the aging Mac platform thanks to the high speed and efficiency of the chipsets. Apple originally promised a two-year transition, but it took three years for the high-end desktop Macs to get Apple Silicon.

M-series Mac models for sale

Mac Features

Pick up any Mac, and it will function the same as the others — with some caveats. Thanks to macOS, there will be little to no difference between how a desktop and a laptop perform. Much of the differences today lie in the processor type being used, not the machine's form factor.

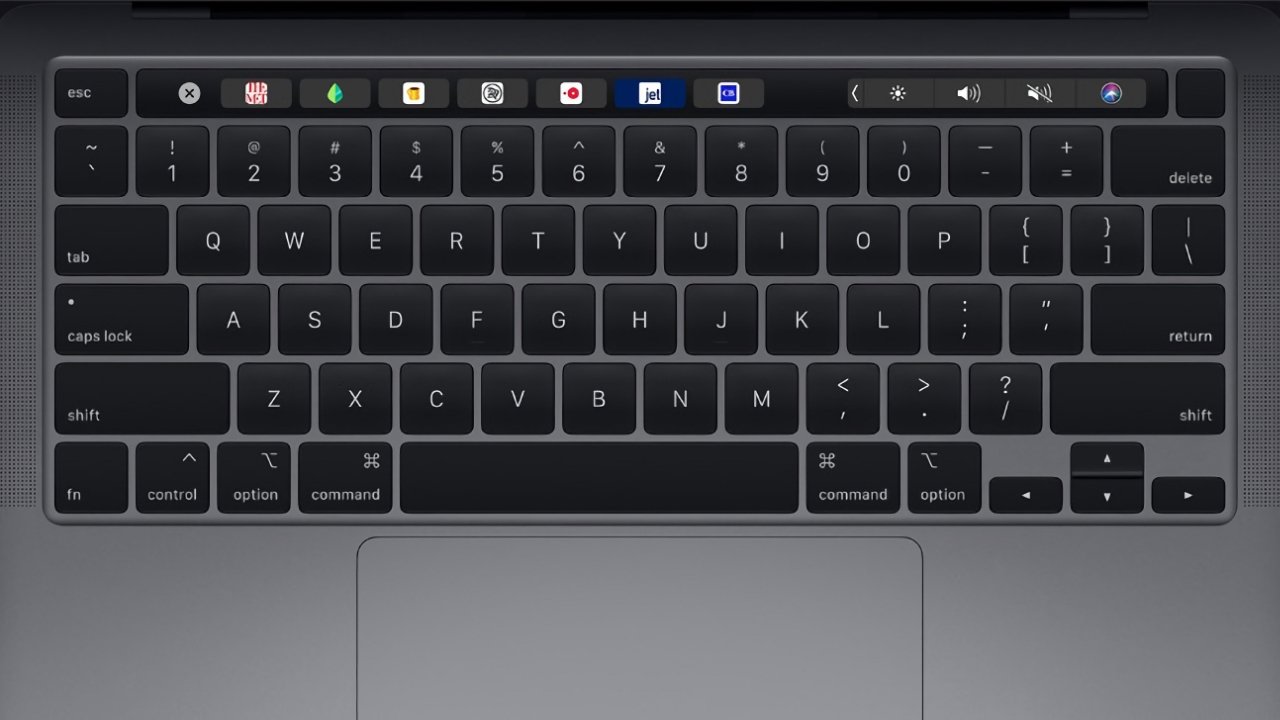

Touch ID is available on all modern Macs via either the built-in keyboard or an external Magic Keyboard sold by Apple. The Touch Bar has been retired and was used until the 13-inch MacBook Pro was discontinued in 2023.

macOS

The current version of macOS reflects Apple's decade of work trying to perfect the operating system. Mac OS X was the tenth iteration of the Mac operating system and debuted in 2001. The Mac OS X name stuck around for fifteen years but changed to macOS in 2016 to bring the naming scheme in line with Apple's other operating systems.

The OS stayed with 10.x versioning until 2020 when the shift to Apple Silicon and a foundational change in how specific systems were managed led to the version number increasing for the first time in a decade. macOS Big Sur was the first to buck the trend as it was version 11. The 2021 operating system release was macOS Monterey 12.0, followed by macOS Ventura 13.0, then macOS Sonoma 14.0, and now macOS Sequoia 15.0.

The Unix-based operating system should be instantly familiar to anyone who has interacted with a Mac in the past. Graphic elements and features change over time, but the overall layout and interaction schemes remained relatively the same. Opening an app would create an app instance in a window. However, closing a window would not close the app but rather leave it running in the background. The traffic light icons control the window management.

The most significant user-facing changes in recent years have revolved around security and bringing the desktop closer to iOS design paradigms. Windows have rounded corners now, apps use sidebars for navigation, and app permissions are more robust than ever.

Apps

While the Mac went through its two-year transition to Apple Silicon, it used a program called Rosetta 2 that translated Intel-based Apps on the fly. This process is so efficient that the M1 Macs can run some Intel apps better than premium Intel Macs.

Ultimately, Rosetta 2 is only a stopgap that Apple will remove in future updates — developers are expected to transition their apps to Apple Silicon or be left behind. Rosetta 2 is still available in macOS Sonoma.

All of Apple's apps have already been written for the ARM, so Final Cut Pro and Logic work at full speed on the new machines.

While Apple continues to push users to the Mac App Store, apps can still be downloaded directly from the web. Some apps require some additional security hoops to jump through, but still work.

M-series Processors

Apple released its first three Macs with an M-series processor at the end of 2020. The 13-inch MacBook Pro, the M1 MacBook Air, and the Mac Mini. The processor was an immediate success, with users noting performance gains and quality-of-life improvements across the board.

The first iteration, the M1, is what Apple says the company can do when it brings its processor expertise to the Mac without much effort. The first machines are identical in every way to their Intel counterparts except for the processor.

With the release of the 2021 MacBook Pros, Apple announced the M1 Pro and M1 Max. These processors take the magic of the M1 even further with 10-core processors and up to 32-core GPUs. Very few Intel-based machines are able to compete in pure computing power.

Apple announced the M1 Ultra for use in the Mac Studio during a 2022 March event. It is the last M1 processor variant in the lineup and is expected to be included in a Mac Pro update later in 2022.

The M2 processor was announced during WWDC 2022 alongside an M2 MacBook Air and a processor bump in the 13-inch MacBook Pro. It is a slightly more powerful processor and a direct successor to the M1.

The M2 Pro and M2 Max were revealed in January 2023 and included in a spec-bumped MacBook Pro lineup. The Mac mini also gained the M2 and M2 Pro, widening its range of usability and performance greatly.

During WWDC 2023 in June, the M2 Ultra was revealed. It is available in the Mac Studio and Mac Pro.

Continuing the blistering pace, Apple released the M3 family of chips all at once in October 2023 — M3, M3 Pro, and M3 Max. These chips launched in the 24-inch iMac and the MacBook Pro.

Apple revealed M4 with the iPad Pro in early 2024 and brought the chip to Mac in October. A redesigned smaller Mac mini got the M4 and M4 Pro, while the iMac was updated with M4.

M4, M4 Pro, and M4 Max were included in the new MacBook Pro lineup. Little else changed in the spec update beyond a brighter displays, Thunderbolt 5 in high end models, and a Nano Texture option.

The Mac Studio and Mac Pro were skipped over in 2024 as Apple seems intent on skipping over M3 Ultra. The 3nm process used for M3 is undesirable, so Apple is quickly moving the lineup to M4.

Intel

Apple cut off Intel entirely at the beginning of the Apple Silicon transition. Intel has had years of near-identical processor bumps with little user-facing improvements along the way. This led Apple to jump to internally-designed processors to ensure Mac's future was in its full control.

With each new M-series processor and Mac using it, Apple cut out more and more Intel machines from the lineup. After the M2 Ultra made it into Mac Pro, Apple no longer sells Intel models.

Some Intel-based machines are still for sale at non-Apple distributors, but they will sell out eventually.

Magic Keyboard

Apple refers to multiple products as the Magic Keyboard, but when discussing Macs, it applies to two — the built-in MacBook keyboards and the wireless keyboard. The new built-in Magic Keyboard uses scissor-switch mechanisms to ensure the keys function correctly with each press.

Apple tried using a "butterfly" mechanism in its MacBook keyboards, but this proved to be a reliability disaster. Users reported that keys would stick or fail regularly, so Apple finally reverted to the scissor switch, but with a new slimmer design.

Apple's wireless keyboards all use the old scissor-switch mechanism but remain thin and light despite the aging design. The external Mac desktop keyboards were updated with Touch ID and colors that match the 24-inch iMac, but little was changed about the overall shape and layout.

Magic Mouse and Trackpad

Apple's trackpad has always been ahead of the competition in terms of reliability and usefulness. The Magic Mouse, however, is a bit of an anomaly.

The Magic Trackpad can connect via Bluetooth or a USB-C cable and uses taptic engines to simulate a click. The entire surface of the trackpad is "clickable" and doesn't physically move when pressed. The taptic engine vibrates during operation to fool users into thinking the device actually clicked.

The Magic Mouse is a small classically-designed mouse that uses touch-sensitive glass for input. Rather than having traditional mouse buttons, the entire top front of the mouse is clickable, and each side can recognize when pressed to simulate right and left clicks. Instead of a scroll wheel, the Magic Mouse uses a touch surface that users can swipe on.

The Magic Mouse is controversial because it can only be used over Bluetooth and charges via USB-C when upside-down. The port placement was an obvious form-over-function choice from an "old Apple" that wanted the mouse to look seamless — even at the detriment of usefulness.

Pro Display XDR

Apple may have said it is out of the display business, but it revealed the Pro Display XDR alongside the Mac Pro in 2019. This 6K display has been calibrated to represent near-perfect color and contrast representation when showing images. Apple says it is competitive with $24K reference monitors used by film professionals.

Customers can add a nano-texture to the display for an additional $1,000. Controversially the monitor doesn't come with a stand. Customers must choose between an expensive VESA adapter or a $1,000 stand.

The Pro Display XDR results from Apple's desire to achieve perfection and features a price to match. Some rumors speculate that Apple is planning on more consumer-friendly monitors in the future.

Studio Display

Apple introduced the Studio Display as a companion to the Mac Studio. It is a 27-inch 5K display with True Tone and P3 color. It connects via Thunderbolt 3 and integrates with macOS features like Spatial Audio and Center Stage.

This new monitor runs an A13 for audio, microphone, and camera processing. It works with modern Intel Macs, all M-series Macs, and the latest iPads with the M1 processor.

The 27-inch iMac was discontinued after the Studio Display was announced. It isn't clear if Apple could still revive the product at a later date with Apple Silicon.

Thunderbolt

Apple uses Intel's Thunderbolt spec across all of its Mac computers. M1 Macs use Thunderbolt/USB-4 connectors while the M1 Pro/M1 Max MacBook Pros use Thunderbolt 4.

Thunderbolt 4 allows up to 100W of power and 40GB/s of data over a single USB-C cable and is fully backward compatible with previous cable specs. The spec also allows multiple Thunderbolt devices to be chained together to maximize the one connection's utility.

The M1-based Macs have some limitations when using Thunderbolt, however. Users can only connect one external monitor via a Thunderbolt connection and cannot use e-GPUs. The monitor support is expected to increase in future iterations of the M-series processor, but e-GPU support may never come.

The 2021 and later MacBook Pros can connect multiple external displays thanks to improvements with the included Thunderbolt controllers.

M4 Macs can connect to two 6K external displays, or three in the case of the Mac mini. The high end Mac mini and MacBook Pros have three Thunderbolt 5 ports.

Touch Bar

The Touch Bar is an OLED strip that appeared at the top of old MacBook Pro models. It replaced the function row keys as a new variable input device for certain apps. Apple had iterated slightly on the Touch Bar design, like re-introducing a physical escape key, but little else changed over the years.

The Touch Bar had been neglected in software too. Apple paid little attention to the hardware when updating macOS or its apps, and third parties have mostly ignored it as well.

Apple originally introduced the Touch Bar as a new interaction paradigm that would give pro users a new way to interact with apps. It offered a novel way to scrub timelines or switch between tools in certain apps but left a lot to be desired otherwise. The lack of haptics and accidental touches made the Touch Bar more of a nuisance for some users than a boon.

With the release of the 2021 MacBook Pros, Apple removed the Touch Bar in favor of full-sized function keys. The company didn't bother to mention the Touch Bar once during the announcement, signaling its demise.

It survived in only one model thanks to a lack of redesign — the 13-inch MacBook Pro. Apple discontinued that model in 2023, thus finally killing the Touch Bar entirely.

History of the Mac

The Mac began in 1979 with Jef Raskin, initially Apple's 31st employee and taken on as Manager of Publications. Having broad experience in computing and regularly using what he called his "honorary beanbag chair" at Xerox PARC, he knew about its graphical user interfaces (GUIs) before Steve Jobs did.

Raskin consequently wanted a graphical bitmapped screen for a computer, but he also had very many more aims for what he saw as the future of the technology. Sometime around March 1979, he lobbied then Apple chairman Mike Markkula to begin a project he initially called "Annie," but later renamed Macintosh.

Far more than some verbal pitch or vague request to work on a new project, Raskin wrote up an entire set of papers that he ultimately called "The Book of Macintosh." The complete text, now available online, ranges from an "Annie" memo of May 1979 to a "January 1980 Overall Summary."

Right from the start, though, the core aim was to make a computer that was simple to use.

"This is an outline for a computer designed for the Person In The Street (or, to abbreviate: the PITS)," wrote Raskin. "[One] that will be truly pleasant to use, that will require the user to do nothing that will threaten his or her perverse delight in being able to say: 'I don't know the first thing about computers, and one which will be profitable to sell, service and provide software for.

When he first proposed "Annie" –– what he really thought would eventually be called the Apple V –– Raskin knew that the company was developing the Apple Lisa. However, Raskin predicted that the Lisa would be "overpriced and too slow."

So as well as a computer for the Person in the Street, he wanted it to be affordable. Raskin's plan was for a computer that cost $500, ran on the low-cost Motorola 6809 processor –– and did not include a mouse.

That lack of a mouse, and so the lack of being able to point and click, means that Raskin may not have envisaged the kind of GUI that we now imagine. At the same time, the Apple Lisa may not have always been planned to have a GUI –– until Steve Jobs saw one at Xerox PARC.

Jef Raskin and Steve Jobs did not get along, but Raskin wanted Jobs to see the work being done at PARC. He called on Bill Atkinson, a principal designer of the Lisa and Mac GUIs, to talk Jobs into visiting Xerox.

The famous visits to PARC in November and December 1979 ultimately led to the Macintosh, but initially, they transformed the Apple Lisa. That project now definitely had to have a GUI, and if Steve Jobs had stayed with the Lisa, Jef Raskin might have got his simple, cheap Macintosh.

However, Jobs reportedly antagonized people enough that Apple's then-president Michael Scott removed him from the Lisa project. Jobs then decided to take over Macintosh and effectively make it better than the Lisa.

This did push Raskin aside, which lead him to leave the project in summer 1981. However, his overall ethos of simplicity, and especially of it being an appliance, stayed. "The computer must be one lump," Raskin had written. "Seeing the guts is taboo."

The low cost, though, and everything that contributed to that did not stay. Raskin formed the Macintosh team, but it was because of Jobs that the Mac ran on the more costly Motorola 68000 and that it got a mouse.

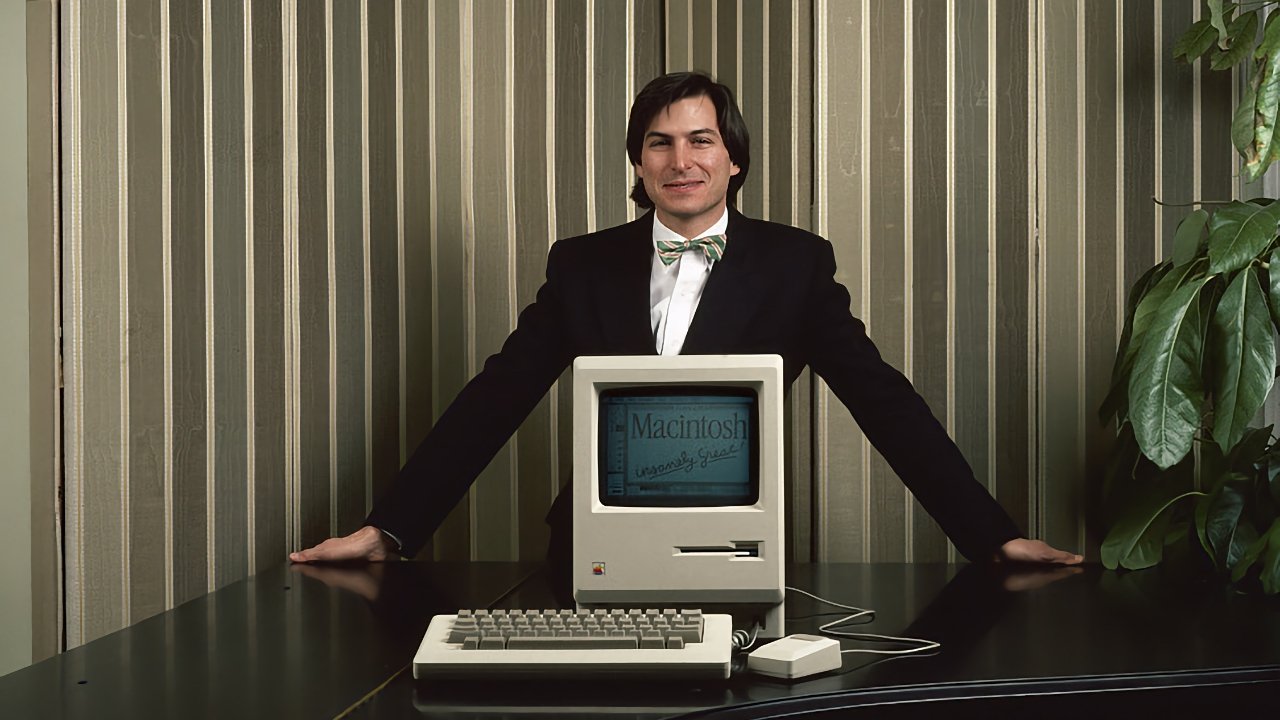

1984 - The Macintosh debuts

By the time it was launched, Raskin's $500 Macintosh had become Jobs's $2,495 one. Some of that was due to then-CEO John Sculley wanting to make back Apple's considerable spending on advertising.

Much of it, though, was Steve Jobs pressing for better components and a better experience for the user. Despite being willing to do that even as it pushed the price up, though, Jobs was not willing to do it enough. The Mac that launched in 1984 was underpowered.

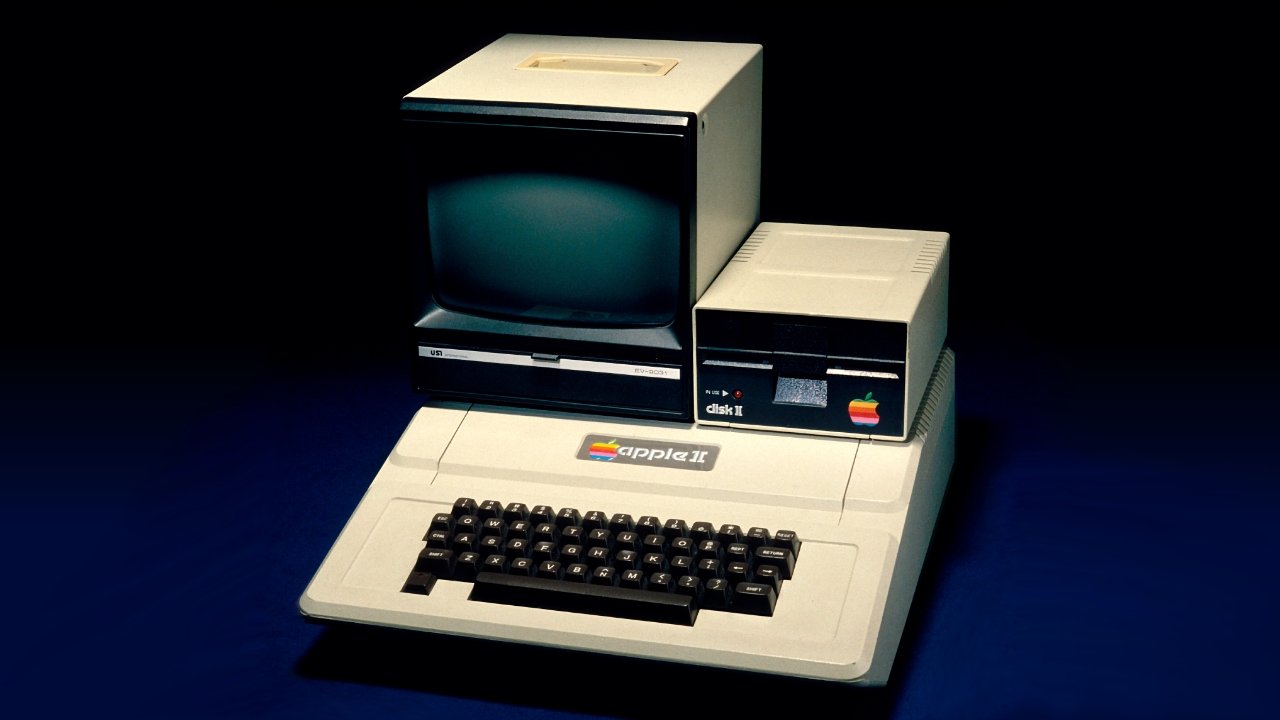

It was also a flop. It changed the world –– truly –– but that original Mac did not change Apple. At least, not at first. For its initial several years, the Mac and Apple were supported by the high sales of the Apple II.

That machine faded away as the original Macintosh became the "Fat Mac," with double the RAM, in September 1984. Then in 1987, came the Macintosh II and the Macintosh SE.

These initial successors just addressed shortcomings in the original Mac. That ranged from the lack of RAM to how it initially only ran in black and white.

Then in January 1989, Apple launched the upgraded Macintosh SE/30. And in 1990, it brought out the "wicked fast" Macintosh IIfx. While other models were popular, and some like the IIci are fondly remembered, these two were arguably the workhorses of the Mac range.

The early 1990s — from innovation to complication with Centris, Quadra, and Performa

Steve Jobs was long gone by the time the SE/30 and IIfx were beloved. His time away from Apple is perhaps more remembered now, though, for what happened next with the Macintosh.

The answer is simultaneously a lot and not very much. The Mac grew steadily more capable and steadily more successful in the late '80s, including the over-engineered but significant Macintosh Portable in 1989.

Unfortunately, the Mac started to become only a little more capable, and it steadily became less successful in the early '90s.

Apple decided to provide a model of Mac at every possible price point and for every conceivable type of customer. Businesses got the Macintosh Quadra range from 1991 and the Macintosh Centris models from 1992, but both were gone by 1995.

Consumers got the Macintosh Performa range, which lasted from 1992 to 1997, but these were just renamed versions of the Quadra, Centris, and LC models. They were given new names, a plethora of marketing model numbers based on starting specs, some cosmetic differences. Then they were sold through big-box stores such as Sears, Service Merchandise, and just about anywhere else that had a pulse and a sufficiently large retail footprint.

Or rather, they weren't. The Performa range, with its dozens of different configurations and models, sold poorly.

However, the two bright spots in this period were the PowerBook range, from 1991, and the transition from 68000 processors to the PowerPC from 1994.

PowerBooks were the "Mac in a book" that Steve Jobs had been pressing for from the start, and their design completely transformed laptops. They moved the keyboard to the back, meaning users' palms rested on the machine instead of awkwardly hanging over the edge. Every single laptop since has copied this.

Similarly, the PowerBook Macs later introduced the trackpad, and practically every laptop since then has followed along.

Even with the PowerBook range's success, though, and the move to PowerPC, Apple struggled because it was spread very thin.

The late 1990s - Jobs returns

Apple was trying to get an updated Mac OS off the ground alongside countless indistinguishable Mac models. With years of effort having nothing to show for it, eventually, Apple began to look at buying in an alternative from outside the company –– and it did.

Apple bought the basis of what would become OS X, but it also brought back Steve Jobs. Apple bought Jobs's failing NeXT Computer in 1996.

"This is a complementary arrangement," then-CEO Gil Amelio said at the time, "The pieces fit together better than any alternative we looked at, and it will launch a new round of technology."

In the long term, Amelio would prove to be correct. But in the short term, he found himself out of a job. It wasn't that Steve Jobs took over –– not at first. Instead, it was the fortunes of Apple that kept on declining, at one point requiring the laying off of 3,000 employees.

There were also public-facing debacles such as Amelio, presenting at Macworld and entirely forgetting to introduce the guest of honor Muhammad Ali. Behind the scenes, Oracle tried and failed to make a hostile takeover bid for Apple –– and it was later revealed that Jobs had supported it.

On July 4, 1997, Apple's board told Gil Amelio he was no longer wanted. He officially resigned as CEO on July 9. Steve Jobs was actually put in charge of finding a replacement, and after a few months, became the interim CEO himself.

"I couldn't even figure out the damn product line after a few weeks," Steve Jobs then said in September 1997. "I kept saying what is this model, how does this fit? I started talking to customers and they couldn't figure it out either, and so you're gonna see the product line get much simpler and you're gonna see the product line get much better."

Jobs' iMac saved Apple

Jobs came in As interim CEO, and then fully the CEO, Jobs sought to save Apple from bankruptcy and did so initially with the Macintosh. Working with Apple designer Jony Ive, Jobs created the iMac.

Announced in 1998, 14 years after the original Macintosh, the new iMac was visually striking, and introduced new technologies that the rest of the industry then emulated.

It also introduced new colors so that the Mac was no longer a kind of yellowing beige, and instead was vivid Bondi Blue, and more. "The one thing Apple is providing now is leadership in colors," Bill Gates said in 1998. "It won't take long for us to catch up with that, I don't think."

That was an example of Gates missing a point because, as Jobs later said, "the only problem with Microsoft is that they have no taste." Where Gates saw color as a quick paint job, Apple saw design as being about everything from how something looked to how it was used.

So alongside its painted exterior, the iMac brought approachability. Jef Raskin had wanted his Macintosh to have a handle, and the iMac still had one. Maybe you never picked it up, but it always felt as if you could, so it seemed lighter than it was, it seemed approachable.

Then it also introduced USB to the wider world. True, the iMac used that technology in the iMac's "hockey puck" mouse, and that was excruciatingly poor. But it brought USB into the mainstream, and rival manufacturers soon fell into the now-familiar pattern of mocking an Apple decision, then copying it.

In 1999, Jobs took the iMac ideas and put them into the iBook. It had similar bright colors, it had a handle, but it also had Wi-Fi. It was the first consumer notebook to have Wi-Fi built-in, and Jobs demonstrated that as if he were a magician, loading up internet pages with no visible wires.

Apple, Intel, and the late '00s

The iMac and the iBook saved Apple, and then from 2001, it did seem as if the company went iPod-mad. That music player became an incredible source of revenue for Apple, and it also introduced Apple to very many users.

Plenty of those users then learned about the Mac, and consequently, its share of the market rose. But with more people using the Mac came more demands on it, and the PowerPC processor was not keeping up.

So in 2005, Steve Jobs announced that Apple was going to undertake another transition, this time from PowerPC to Intel.

"Why are we going to do this?" he said. "Didn't we just get through going from OS 9 to OS X? Isn't the business great right now? Why do we want another transition? Because we want to make the best computers for our customers going forward."

Moving to Intel gave the Macintosh a boost it could not have got from PowerPC. Although it tied Apple to Intel's schedule of releases, it also enabled ever more powerful Macs, including the iMac Pro.

Mac Pro and consumer Macs

When it launched in 2017, the iMac Pro was praised but seen as a stopgap while Apple worked on a revised Mac Pro. Very unusually, the company had even said that it was working on one –– and it did so because, at this point, the Mac Pro was languishing.

Originally introduced as the top-end Mac for power users in 2006, the "cheese grater" machine that evolved from the PowerMac G5, had hit its limits long before the range was replaced in late 2013. That December 2013 Mac Pro was the cylindrical "trash can" model and it failed, mostly because Apple didn't predict the increasing focus on GPU power versus CPU.

It was gorgeous to look at, but unlike its predecessor, it had barely any expandability. Apple would later say that thermal issues in its design limited it.

What it looked to the outside world, and most particularly to power user creatives, was that Apple was focusing more on consumers. It was, too, with the iPhone, and then to a lesser extent the iPad, becoming what Apple was known for.

By 2015, there were eighteen iPhone users for every individual Mac user, and this number has only grown since. Of course, the company served its new core audience –– but the old core audience was drifting away.

Hence the 2017 iMac Pro, then the 2019 Mac Pro. The 2019 Mac Pro was the most expensive Mac in decades, surpassed only by the IIfx, and it could be expanded at a cost greater than all but the most pro users could contemplate.

Apple was telling the power users that the Mac was back. It just very shortly afterward told them the Mac was changing.

Next stop, Apple Silicon

Despite the extremely high performance of the 2019 Mac Pro, being tied to Intel was limiting how much Apple could do when Intel itself was not sticking to its own development plans. Intel processors, as a whole, were hitting limits that Apple needed to exceed.

Customers could see the limitations and the delays, so of course, Apple could as well. In 2020, Tim Cook announced the long-rumored, much-awaited next transition.

The Mac in 2020 would still follow Jef Raskin's aim of being the simplest computer to use, but it is the Apple Silicon M1 processor that would be unrecognizably fast. That's unrecognizably faster than anyone from Raskin's time could imagine, but also faster than even present-day Intel users could.

After releasing the M1, M1 Pro, M1 Max, and M1 Ultra, Apple introduced the M2, restarting the cycle anew. M2 Pro and M2 Max followed in early 2023, with the M2 Ultra arriving later in June.

M3, M3 Pro, and M3 Max were announced in October 2023 with even more improvements. They are the first Apple Silicon chips for Mac built on the 3nm process.

M4 arrived in the Mac in October 2024. The M4 Pro was revealed with the redesigned Mac mini while the M4 is used in the base Mac mini and iMac. M4, M4 Pro, and M4 Max are available in the MacBook Pros, which also have brighter displays with optional Nano Texture.

The M4 Ultra is due in the Mac Studio and Mac Pro in the summer of 2025. The M5 processor should debut before the end of 2025 in select Macs.

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Mike Wuerthele

Mike Wuerthele

Chip Loder

Chip Loder

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

Amber Neely

Amber Neely