Microsoft's Office for Mac 2008 adds new features and a revised user interface to the standard suite of productivity applications including Word, Excel, PowerPoint, and Entourage. Scheduled for release in January 2008, the upgrade will be the first new release for the Mac since 2004, back in the days of Mac OS 10.3 Panther.This report goes to great lengths to explore the origins, history, and maturity of software-based office suites and Microsoft Office for the Mac. For those readers with limited time or who are only interested in what's due in Office 2008 for Mac, you can skip to page 4 of this report.

Ten years ago, Steve Jobs took the stage at the summer 1997 Boston Macworld Expo to announce plans to restore confidence in Apple. Key among those plans was a deal with Microsoft to deliver the first new edition of Office for Mac since Microsoft had halted development back in 1994, prior to the release of Windows 95.

Microsoft recently announced new plans to again introduce a new version of Office for Mac after delays led to a four-year development process. This time, however, Microsoft faces new competition from Apple itself, which has impacted Microsoft's Office 2008 pricing and features. New competition between the two firms in the productivity application arena is great for consumers; here's how the two companies have acted as both rivals and partners over the last three decades in productivity applications, leading up to renewed competition today.

The Origins of Office

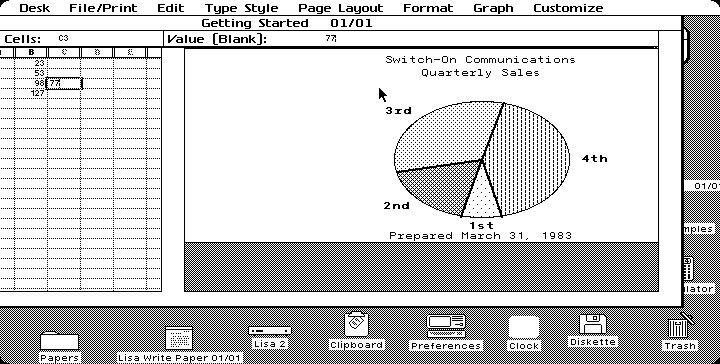

The first graphical office application suite wasn't Microsoft Office, but rather Apple's Lisa Office (below), which debuted in 1983 and was bundled with the Lisa computer. Critics gave the Lisa's application software better marks than the computer itself. However, third party developers were irritated that Apple had delivered a full suite of software with the new system, killing any aftermarket for productivity suites.

Apple hoped the Lisa would move microcomputers into the realm of office business machines, but sales for the $9,995 systems were slow in coming, particularly in comparison to the expectations Apple had set for it. The Apple II had sold 16,000 units in its second year and was considered a success; the Lisa sold nearly 100,000 units but was considered a failure--by 1983, the Apple II was selling a million units per year.

Despite its sales not meeting expectations, Lisa systems were widely deployed as shared systems in many large and medium sized offices, exposing a broad audience of office workers to the new graphical desktop, the mouse, and windowed documents that had until then only existed in technology demonstrations. Lisa computers demonstrated the practical utility of a graphical interface for tasks such as project management and document publishing, delivered via its bundled Lisa Office apps.

In parallel with work on the Lisa, Apple had also funded development of the Macintosh as a lower priced system aimed at volume sales and individuals. Faced with limited resources, the smaller Mac team could only deliver a subset of the Lisa Office applications on the Mac; instead, it worked to promote interest among third party software developers similar to the market that had sprung up around the Apple II with VisiCalc. However, even more momentum had been growing behind IBM's 1981 DOS PC, with specialized applications such as WordPerfect's word processor and the Lotus 1-2-3 spreadsheet serving as major reasons to buy the machines.

Microsoft's Applications for Macintosh

After taking over the Macintosh project, Jobs began courting third party developers but found limited interest. Developers were delivering applications for DOS PCs because of the large installed base. Apple's last two systems--the 1981 Apple III and the 1983 Lisa--had both failed to sell in impressive numbers.

Offering software for Apple's new Macintosh was a big gamble; it required additional investment in learning how to write software designed to specific guidelines and using Apple's unique Mac Toolbox, neither of which could be ported back to DOS or other systems if the Mac failed in the market.

In 1981, Jobs approached Microsoft's Bill Gates about developing for the Mac. The two companies had already partnered to produce Applesoft BASIC for the Apple II, and Jobs knew Microsoft wanted to get into the applications business, but that it faced difficult odds on the PC platform against entrenched competitors. That left Microsoft willing to explore other platforms. Microsoft was preparing to release a VisiCalc-clone called Multiplan, and subsequently delivered versions for the Apple II, Commodore 64, and TI-99/4A; the company's circumstances similarly pushed it into the role of an early adopter of the Macintosh when few others expressed much interest.

Apple signed a deal in 1981 that gave Microsoft early access to Macintosh prototypes and development tools in exchange for the delivery of Multiplan for Macintosh, with the understanding that Microsoft wouldn't deliver any mouse-based software for the PC until a year after the Mac shipped. At the time, Apple planned to ship the Mac in 1982, limiting the exclusive deal to late 1983. That same year, Microsoft hired Charles Simonyi and Richard Brodie--who had developed the Bravo word processor at Xerox PARC--to port Bravo as a companion word processor to Multiplan called Multi-Tool Word.

Microsoft's DOS Applications

In 1983, Microsoft announced Multi-Tool Word for DOS (below), which shipped with a mouse for the PC. Apple was outraged, as it had not yet shipped the Macintosh. However, Microsoft was able to exploit a loophole in its contract with Apple, which had set a fixed date for the exclusive period ending in 1983 rather than explicitly floating the clause to the Mac's actual release date, as Andy Hertzfeld described in A Rich Neighbor Named Xerox.

Even so, both Multiplan and Multi-Tool Word (later renamed Word for DOS) found little interest among PC users trained to use the conventions of Lotus 1-2-3 and WordPerfect. In contrast, Microsoft's applications had far less initial competition on the Macintosh, where Multiplan was released under the new name Excel in 1985, next to the first graphical version of Word (below).

Much of the reason for Microsoft's success on the Mac but failure on DOS came from the fact that it followed Apple's user interface guidelines on the Mac, so its new applications worked the same as every other program on the system. On the DOS PC, every application used its own keyboard shortcut conventions. While Excel and Word shared many of the same commands, nobody was familiar with them. The market preferred to continue using the applications they'd already learned, including Lotus 1-2-3 and WordPerfect.

Early Mac Apps

While Jobs partnered with Microsoft, Apple also worked on its own applications. The Mac team contracted with former Apple employee Randy Wigginton to develop MacWrite (below), which was bundled on new Macs. Jobs also outsourced a parallel effort to produce a second Mac word processor as a contingency plan in case MacWrite was not finished on time.

That effort resulted in WriteNow (below), a fast and lean application that was later sold independently as a commercial product. After Jobs left Apple, he bought WriteNow and sold it through NeXT. It later became the included word processor for NeXT systems.

Unlike Microsoft, other vendors who developed for the Macintosh frequently failed to grasp the human interface guidelines Mac users quickly came to expect. WordPerfect's' initial release for the Mac was panned for being too much like DOS. Lotus' attempt to deliver a Mac spreadsheet called Jazz was a similar failure. Both were derided by the Macintosh press for not being "Mac-like," and both companies later delivered new versions that worked closer to what Mac users expected.

While delivering a highly revised WordPerfect 2.0, the company complained about Apple's bundling of MacWrite, and also later complained to NeXT about its bundling of WriteNow. As a result, Apple spun its own Mac applications off into the Claris subsidiary in 1987, which sold apps such as MacWrite separately. NeXT also removed WriteNow and replaced it with a simpler, stripped down text editor called TextEdit (below), which eventually found its way into Mac OS X.

That same year in 1987, Microsoft purchased Forethought, a Mac software developer which had released a presentation software program called PowerPoint (below) that spring.

On page 2 of 4: Microsoft Launches its Mac Apps on the PC; Microsoft Develops Windows for OS/2; Windows 3.0 Gets Bundled on PCs; Microsoft's Mac Applications Stall: Office 4; and Microsoft Focuses on Windows.

Microsoft Launches its Mac Apps on the PC

Two years after being surprised by the submarine launch of Word for DOS, Apple signed a new agreement with Microsoft for exclusive delivery of Excel for the Macintosh over a two year period. Gates tied the agreement into the expiring Applesoft BASIC contract as a way to kill Apple's MacBASIC, as noted in An Introductory Mac OS X Leopard Review: Developer Tools. Gates also demanded Apple provide a free license to Microsoft for the use of Macintosh technology in Windows 1.0.

That agreement proved to be devastating for Apple, because Microsoft subsequently used it to deliver its Mac-like environment for DOS as a way to port its Mac applications to the PC. While Microsoft had demonstrated Windows 1.0 in 1983, it didn't actually ship the product commercially until late 1985 (below), after signing its licensing agreement with Apple. Historical revisionists like to suggest that Microsoft independently delivered Windows 1.0 and Word for DOS in advance of the Macintosh, and trained Apple in how to use the mouse.

The Windows environment was largely worthless without any real applications to run on it. When the two year exclusive period for Excel expired in 1987, Microsoft shipped Excel 2.0 (below) with Windows 2.0. Apple sued Microsoft over the use of additional Mac technologies not covered under the earlier license, including the invention of Regions, which enabled the use of overlapping windows. That lawsuit continued into 1994, at which time the court ruled that Apple's original 1985 agreement had been too vague in what it covered, and largely dismissed the entire suit for that reason.

While Microsoft's Multiplan for DOS never got much attention, the prospect of running a graphical Excel on standard PCs did, and Microsoft began eating into Lotus' market share. In 1989, Microsoft shipped Word for Windows, and then in 1990 shipped Windows 3.0 along with PowerPoint for Windows.

Microsoft Develops Windows for OS/2

While Microsoft continued to make most of its money from Mac applications, it had entered into a partnership with IBM in 1985 to develop a replacement for DOS called OS/2. Microsoft and IBM planned to migrate the Windows environment to run on the new foundation of OS/2, effectively transferring Apple's technology directly to IBM, part of the reason Apple sued Microsoft over its look and feel lawsuit; Apple did not sue Atari, Commodore, Acorn, and a variety of other vendors offering graphical user interfaces.

As development of OS/2 continued, Microsoft began to describe it as "Windows Plus." It also developed "Windows Libraries for OS/2," also known as WLO, and used these to port Word (below) and Excel to OS/2. Microsoft advised DOS application vendors--including Lotus and WordPerfect--to port their applications directly to OS/2's native libraries instead.

At the same time however, Microsoft was deeply invested in its own solo plans to deliver a new operating system. In 1988, Microsoft hired Dave Cutler and his team of operating system developers from Digital, and began work on what would eventually ship as Windows NT. When asked if Microsoft would develop for Jobs' NeXT computer, Gates revealed his disinterest in anything outside of Windows by answering, "Develop for it? I'll piss on it."

Microsoft continued to ship Office apps for OS/2 into 1992, and advertised OS/2 compatibility for Windows NT when it was released in 1993. At the same time, it clearly had no interest in maintaing support for OS/2. This effectively led existing DOS developers into a blind alley, allowing Microsoft to promote its own applications on the PC as the only options available for Windows users. Some Microsoft supporters now claim that the entire DOS software industry simply failed to deliver Windows applications on time. Additionally, while WordPerfect could complain about rival word processors bundled by Apple and NeXT, it could not complain to Microsoft, which was pointedly and intentionally competing against WordPerfect.

Windows 3.0 Gets Bundled on PCs

Sales of Windows 3.0 began to quickly take off after PC makers--lead by Zenith--began to ship Windows 3.0 pre-installed with new PCs to compete against Apple. No earlier versions of Windows had ever been pre-installed on new PCs before.

In reviewing Windows 3.0, John Dvorak noted, "I think Windows 3.0 will get a lot of attention; people will check it out, and before long they'll all drift back to raw DOS. Once in a while they'll boot Windows for some specific purpose, but many will put it in the closet with the Commodore 64."

As sales of Windows 3.0 increased, Microsoft publicly pulled out of its OS/2 partnership with IBM, leaving DOS application developers invested in a system without any future. That enabled Microsoft's own Word and Excel to eclipse WordPerfect and Lotus 1-2-3 on the PC, as noted in Office Wars 4 - Microsoft’s Assault on Lotus and IBM. Microsoft even began bundling Office 95 licenses with new PCs, further destroying any functional market for third-party Windows software in any industry Microsoft chose to enter.

Microsoft's Mac Applications Stall: Office 4

Microsoft delivered new major versions of Word on the Mac every two years in 1985, 1987, 1989, and 1991 (below, Word 5 was $495), and matched this with new versions of Excel in 1988, 1989, 1990, and 1992. In 1990, Microsoft bundled Word, Excel and PowerPoint into a package called Microsoft Office for the first time, seven years after the original release of Apple's Lisa Office.

As sales of Windows 3.0 increased, however, Microsoft shifted its interest from the Mac to its own platform. 1991's Word 5.0 for Macintosh had been highly regarded, but it lacked some of the features Microsoft added to the parallel release of Word for Windows 2.0. Hampered by maintaining separate versions for the Mac and Windows, Microsoft decided to develop a single, cross-platform code base for Word under the code name Pyramid.

Facing competitive pressure from WordPerfect however, Microsoft decided to scrap plans to rewrite a unified Word code base, and instead simply ported its existing Word for Windows 2.0 code to deliver Word 6.0 for Macintosh. Microsoft ran into a series of problems related to differences and limitations in the classic Mac OS, which led to the near infamous reputation of Word 6 (as Microsoft's developer Rick Schaut described in Buggin' My Life Away : Mac Word 6.0).

In part, this was because it required more resources; it had been designed to run on Windows, and was now competing for attention on the Mac against Word 5.1, which was custom written for the Mac and designed around its peculiarities. However, Word 6 was also criticized for simply being different. Some significant improvements Microsoft delivered were hated by existing users simply because they required the user to unlearn earlier, more complicated ways of performing the same tasks.

Microsoft Focuses on Windows

Shortly after the troublesome release of Office 4 for Mac in 1993--which included Word 6, Excel 5, and PowerPoint 4--Microsoft put development for the Mac on hiatus and focused on Windows. Microsoft then delivered:

- a 16-bit Office 4 for Windows in 1994.

- a new 32-bit version of Office 4 for Windows NT in 1994 which ran on MIPS, PowerPC, and Alpha in addition to PCs.

- Office 95 with the release of Windows 95 in late 1995, which jumped internally to Office 7 to match the version of Word; there was no Office 5 or 6.

- Office 97 in late 1996, also called Office 8.

During the period where Microsoft gave up on the Mac, WordPerfect released significant updates that incorporated support for unique features of Apple's System 7 (below, running WordPerfect 3.5). The company then abandoned the platform in 1996 and announced it had no interest in ever returning.

Nisus also capitalized on Microsoft's absence in the Mac market to deliver updates to Nisus Writer (below).

On page 3 of 4: Apple's Claris; Apple, Microsoft and the New MacBU; Office for Mac 98; Office for Mac 2001; Office v.X; Office for Mac 2004; and Apple Launches iWork.

Apple's Claris

Apple's own Claris software subsidiary delivered a hit and miss strategy that oscillated between promoting its Mac apps and then allowing them to stagnate. In 1990 Claris launched ClarisWorks, which competed against Microsoft's Works program as an integrated office application with multiple modules. After becoming popular on the Mac and outselling Works, Claris began offering a Windows version.

Claris subsequently developed and acquired a variety of Mac software titles, including Resolve, based on the Informix WingZ spreadsheet; the FileMaker desktop database; the popular Emailer mail client; and the Organizer calendar.

While its software was well regarded, the company ran into increasing difficulties that mirrored those of Apple: erratic management problems and a lack of clear direction. This resulted in a loss of engineering talent while an existing portfolio of applications fell behind. Claris' fate was sealed when Apple decreed that it would implement its popular ClarisWorks product using OpenDoc to prove it could be done. By 1996, Claris' portfolio of apps was in the same rough shape as the Mac OS, as described in Claris and the Origins of Apple iWork.

Apple, Microsoft and the New MacBU

After Apple acquired NeXT, it announced a new OS strategy called Rhapsody, which essentially rebranded NeXTSTEP with the Mac appearance. Third party developers, burned by a series of Apple's engineering dead ends including OpenDoc, QuickDraw GX, and Copland, refused to support Apple's new strategy, sending it back to the drawing board.

Apple was back to 1981, with a new platform coming out and no developers to write for it. Once again, it had garnered a sketchy reputation from recent software development failures on the level of the Apple III and Lisa, and its existing Mac hardware business was now looking as long in the tooth as the Apple II had fifteen years prior. Also like before, Jobs made a deal with Microsoft that ensured new software would be released for it.

Jobs' deal with Microsoft resulted in a five year commitment to deliver Office on the Mac in tandem with Windows releases. It also ended the remains of the disputes that had dragged along since the late 80s. In the Microsoft monopoly trial, Apple Software Engineering VP Avie Tevanian testified that Apple had additionally "put Microsoft on notice in 1996 that its Windows operating systems and Internet Explorer infringed Apple's patents." Also related in the deal was Apple's ongoing lawsuit over Microsoft's infringement of QuickTime in the Canyon case, as described in Mac Office, $150 Million, and the Story Nobody Covered.

Apple and Microsoft would now work together, with Microsoft delivering Mac Office apps and a web browser that Apple lacked the resources to develop on its own, in exchange for Apple ending its ongoing litigation against Microsoft and receiving a $150 million vote-of-confidence stock deal. While some Apple faithful criticized the deal, it kept the classic Mac platform alive until Apple could replace it with a retrofitted version of NeXT's technology.

Earlier in 1997, Microsoft had announced the formation of the Mac Business Unit as an independent group within Microsoft devoted to developing Mac software. The MacBU had 145 employees, which represented the second largest Mac development group outside of Apple.

Office for Mac 98

The following year, the MacBU released Office for Mac 98 (below), which delivered much of the look and feel of Microsoft's Office 97 for Windows from a year and a half prior. The release was plagued with bugs, but was received as a welcome addition given the four years of no new versions of Office for Mac.

A UGeek Software Review underscored the warm recepton: "Microsoft Office 98 for Power Macintosh has exceeded all expectations," it said. In response to the Word 6 fiasco, the new release allowed users to choose between using the old Word 5 menu layouts or new ones that matched Microsoft's Windows version. It also introduced other new features from Windows versions of Office, including the background spell and grammar checking highlighted by underlined squiggles. It was also PowerPC only, dropping support for older 68K Macs.

Meanwhile, Apple absorbed Claris in 1998 and began selling ClarisWorks for the Mac under the name AppleWorks. In 2000, Apple released another revision of ClarisWorks as a Carbonized application, allowing it to run on both Mac OS 9 and the coming Mac OS X. Even at the time, however, it was clear Apple didn't have big plans for AppleWorks, and hoped to instead replace it entirely.

Office for Mac 2001

Microsoft delivered its next version of Office for Windows in January 1999 as Office 2000. It followed up nearly two years later with Office for Mac 2001 in October 2000. Users of Mac OS X were disappointed to find that Office 2001 wouldn't run natively on the upcoming operating system. Instead, it required the Classic environment.

The list price was $500, with a $430 street price and $300 upgrade. Despite two years of work, Office 2001 offered little over the 98 version apart from tweaks such as the Project Gallery (below) and an extended open file dialog that opened at launch.

ATPM's Review: Microsoft Office 2001 noted that "Microsoft Office 2001 for Mac fulfills Microsoft’s legal obligation to maintain its application suite on the Macintosh platform," but complained that the Mac version didn't match features in the Windows version from nearly two years prior. The review called it a "mediocre upgrade to Office 98" and said users had little reason to upgrade. "Most of the new features are awkward, poorly documented, bug-ridden, or all three."

Office v.X

A year later, Microsoft delivered Office v.X (Office 10) in November 2001, just six months after delivering Office XP for Windows. Microsoft delivered the new suite using Carbon, which allowed it to port Office 2001 to Mac OS X with much less effort. However, it still had to revise the look of the entire suite to match the new Aqua interface. In doing so, Office for Mac delivered features absent from the Windows version, such as fancy translucent charts in Excel (below).

Microsoft reportedly sold far fewer copies of Office v.X than it anticipated: it shipped about half of the projected 700,000 copies in the first year. This was likely related to the sheer number of Mac users who had already paid for a $500 copy of Office the year prior. The company now wanted another $300 upgrade for v.X just to run it natively on the new OS, which itself had limited adoption prior to the release of Mac OS X 10.2 Jaguar in 2002. This prompted Microsoft to release a variety of Office packages at different price points.

A Professional Edition bundled in the Virtual PC Windows emulator that Microsoft had acquired from Connectix in 2003. The company used this as an excuse not to port Access, Visio, and Project, as MacUser noted in its Review. Microsoft also added the free Remote Desktop Connection client as a reason to pay the $500 price.

A Standard Edition was offered for $400, and an Student and Teacher version was offered for $150. As for policing the education version, the then general manager of the MacBU Roz Ho stated only that Microsoft had an end-user license agreement it believed its customers would honor.

Office for Mac 2004

Two and a half years after the release of Office v.X, Microsoft released Office 2004 (Office 11) in May 2004, again just six months behind the release of Office 2003 for Windows.

MacNN's Review: Microsoft Office 2004 summarized the update well:

"The new version offers some really cool bells and whistles that the prior version did not, across all four applications that make up the Office suite," it said. "There is slightly better compatibility with the Wintel versions of Word that will make it possible for you to more completely share your work with our less-fortunate brethren of that other platform. However, many of you already using Office v.X may decide that what you have is already good enough… good enough that you don’t need the upgrade. In that respect, Microsoft’s chief competitor may be itself."

Among the new features were voice recording (below) and a Project Center that linked together related contacts, documents, and events in a single dashboard interface.

Apple Launches iWork

A year prior to the release of Office for Mac 2004, Apple released Keynote as a $99 new presentation alternative to PowerPoint. A year afterward, it released Pages as a similarly designed page layout program, packaged with Keynote for $79. The next year, the same team at Apple released iWeb, which was bundled with iLife, along with a revised iWork 06 package.

This year, Apple released iWork 08, which bundles in Numbers (above) as spreadsheet, presents new animation and narration tools in Keynote (below top) and adds word processing features to Pages (below bottom). The iWork 08 package now delivers direct competition with Office for $79, and takes advantage of Mac OS X features, such as integration with iLife and standard toolbars and interface elements shared with other Mac applications.

On page 4 of 4: Office for Mac 2008; What's New in Office 2008; A Mixed Bag; and A More Sophisticated Palette.

Office for Mac 2008

Ten years after the 1997 deal between Apple and Microsoft, the two companies are again directly competing in productivity applications. While Apple's latest iWork 08 offers a reworked, simplified approach to page layout, word processing, presentations, and spreadsheets, Microsoft's upcoming Office 2008 suite layers together elements of the unified Leopard interface with concepts borrowed from the Windows version of Office--including bits that look like they belong in Windows Vista. While offering a lot of new ideas of its own, the MacBU has also worked to closely follow the Windows version, making it easy for users to move between them.

Originally expected this summer, Microsoft announced a six month delay in the arrival of Office 2008, which now targeted for mid January, a full year behind the Windows version of Office 12. Faced with competing against iWork, Microsoft has also relaxed the restrictions in its education version pricing. It will now offer Office 2008 in three reworked packages:

- The new Home and Student Edition is now $149, with no restriction to education buyers.

- The Standard Edition is $400 ($230 upgrade). It adds "full support" for Exchange Server in Entourage and Automator scripting.

- A new Special Media Edition costs $500 ($300 upgrade). Since Virtual PC is now obsolete, Microsoft acquired the QuickTime-based iView MediaPro and now includes it under the name Microsoft Expression Media, as an asset management suite designed to import, annotate, organize, archive, search, and distribute media files.

What's New in Office 2008

Like the v.X and 2004 versions before it, Office 2008 is a significant release. It's now a Universal Binary, allowing it to run natively on Intel Macs rather than relying on Apple's Rosetta translation technology used to run PowerPC code. Until today, all Intel Macs have effectively run one of their most important productivity packages in a mode that rendered it artificially sluggish.

Microsoft also adopted an iWork-style template-based design in Word (below top), Excel (below middle), and PowerPoint (below bottom).

Along with those main applications, Office also includes the most recent version of MSN Messenger and new revision to Entourage, which includes the new My Day application (below) for presenting events and reminders in an organizer widget view, although on the desktop rather than only within Dashboard.

A Mixed Bag

In some areas, Office 2008 delivers new features missing from both iWork and the Windows version of Office. In other areas, it falls short of its Windows cousin: some elements are awkward and aren't helped by a sometimes ugly mix of user interface elements that look and feel clumsy compared to the unified look of iWork. Whether users can overlook these odd details largely depends on how they use Office documents.

For example, the new Office promises greater compatibility with Exchange Server and the Office 2007/OOXML file formats supported in the Windows version. While iWork already offers support for these formats, Microsoft uses them natively, not just for import and export. If you are constantly exchanging documents with Windows users, you might find iWork's translation inconvenient or impractical.

One of the most obvious new changes in Office 2008 is its overhauled user interface. Rather than using the floating button bars Office has always used (above, Word 2004), the new version adopts the look of standard Mac OS X toolbar within the document window (below). This offers user configurable icon layouts, although not in the standard drag and drop sheets Mac users will expect.

Below the new toolbar is the new Elements Gallery (above, the blue section), which displays a menu of templates and themes as well as selection of graphics, charting, tables, and text art tools. Its new animated and colorful interface may sometimes be labeled overpowering and busy, but the oddest aspect is its abrupt juxtaposition in the otherwise subtle grey document window. Among the items displayed in the Elements Gallery are Word's Document Elements, which presents templates for adding a cover page, a table of contents, headers and footers, and a bibliography.

A More Sophisticated Palette

The new Office 2008 apps also present the existing Formatting Palette (as appears above in the Word 2004 screenshot) with new iWork-style Inspector icons (below). This expands the Formatting Palette to include:

- an Object Palette of drag and drop shapes, characters, and clipart.

- a smart looking Citations Palette for managing works referenced in a bibliography.

- a Scrapbook manager for organizing multiple clippings for pasting into documents.

- a Reference Tools section for presenting definitions, synonyms, language translations, and encyclopedia entries.

- a Compatibility Report tool for checking features that may not translate to earlier versions (it saves file formats back to Word 97).

- and a Project Palette for organizing documents and related information together by project.

Some aspects of the new Palette are interesting and seem very compelling, but other portions feel overloaded and largely impractical. Why squeeze a shelf of reference works into the Inspector? Why spin the Inspector around like a Dashboard Widget to present settings (below)? Why use a transition like Apple's "genie" Dock effort to place the Inspector into the Toolbar?

This mixed bag of innovation and oddity runs throughout the new Office 2008. Users wanting access to more sophisticated features will love some of the new features, and might like the new graphical feel of Elements Gallery. Mac users accustomed to the iWork interface and the general look of Leopard may find the new Office excessively animated and garish. Nobody can say its just conservative and boring however.

Coming up next: a preview of how the new Office for Mac compares with Microsoft's latest Windows version, how it stacks up as a modern Mac app, and how the MacBU has changed the Office user interface and installation system over the existing 2004 version.