While Apple's chief executive Steve Jobs said AT&T wouldn't let him reveal its proprietary data about dropped call statistics for competitive reasons, the mobile provider has revealed some numbers in an effort to defend its network from poor dropped call scores collected by ChangeWave.

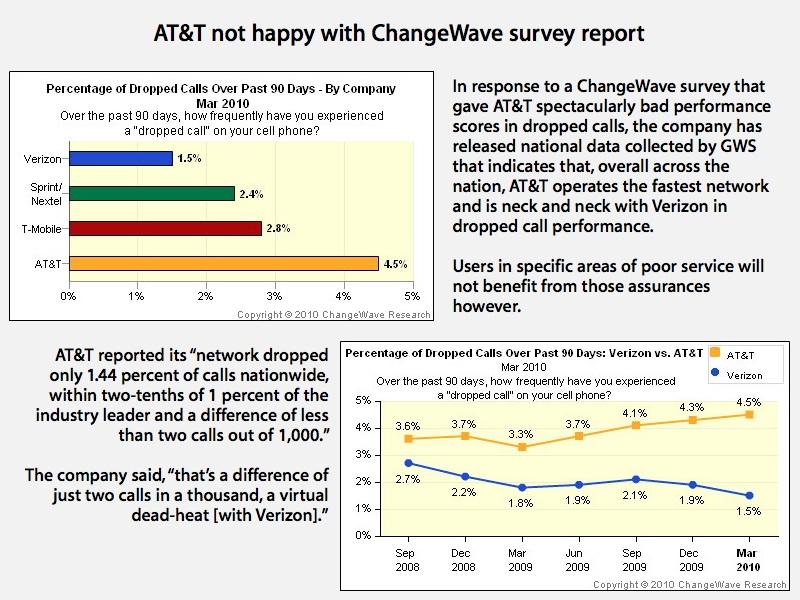

ChangeWave published the results of a March survey which indicated AT&T had much higher dropped calls than its US competitors: 4.5 percent compared to 2.8 percent for T-Mobile, 2.4 percent for Sprint, and just 1.5 percent for Verizon Wireless.

That data was collected by a survey of 4,040 smartphone users who were asked to report their own percentage of dropped calls. AT&T's dropped call rate has reportedly inched higher since September 2008, when it was reported to be 3.6 percent, while Verizon's score improved over the same period from a high of 2.7 percent.

AT&T responds

AT&T was obviously not happy with the numbers, and in response to a Tech-Ex report publishing the ChangeWave figures, pointed to scientific national drive testing performed by GWS, contrasting its "actual quantitative results derived from millions of calls made during extensive drive-testing of the AT&T mobile broadband network by a highly respected outside firm" with "the opinions compiled in the survey" which were "dramatically at odds" with the GWS data.

A "statistically valid drive test shows the AT&T network continues to deliver the nation's fastest 3G network and near best-in-class call retainability nationwide," the company said. "AT&T's network dropped only 1.44 percent of calls nationwide, within two-tenths of 1 percent of the industry leader and a difference of less than two calls out of 1,000."

AT&T noted that "those results, from GWS, show that, on a national basis, AT&T is within just two-tenths of a percent of the industry leader in wireless call retainability. That's a difference of just two calls in a thousand, a virtual dead-heat."

Network, phones and location, location, location

AT&T's numbers likely differ so dramatically for a number of key reasons. In addition to the performance of the network, dropped calls can also be related to the performance of handsets and where they are being used. The fact that AT&T carries more smartphone users and handles more data than all the other US providers combined also has an impact, as it is easier to maintain calls for embedded phones than sophisticated smartphones that may drop a call due to other factors (such as the iPhone 4's proximity sensor flaw).

Different models also have different call drop rates. Even Apple acknowledged that there is a difference between the iPhone 3GS and iPhone 4; while Jobs downplayed the difference as being less than one dropped call per 100, he also admitted that the problem was real and committed to an expensive free case offer to rectify the situation, as case use should help to improve reception by isolating the device from the user's hand.

Apart from performance differences between phones, there is also a major difference in call reliability between users in different locations, whether that is a product of the quality of AT&T's network in a specific location or an issue related to a large number of users located in a overburdened area. That can be a chronic problem or an acute issue caused by a large number of visitors flocking to the same event.

San Francisco Network destroys its own network

Users in areas such as San Francisco with notoriously bad spots of poor or nonexistent coverage are obviously going to see far more dropped calls than users in a area where AT&T doesn't have to fight neighborhood groups working to prevent the installation of any new towers due to fears that their radio output will cause health problems.

Jobs noted that AT&T spends an average of three years applying for new cellular tower sites in San Francisco, compared to just three weeks in other markets such as Texas.

Part of the credit for San Francsicos's terrible cellular service can be attributed to the tireless efforts of the San Francisco Neighborhood Antenna-Free Union (SNAFU), which actively prevents network expansions due to what it calls "mounting evidence concerning the health and environmental effects of radiofrequency (RF) radiation used by cellular phones, cellular antennas and other wireless transmitters."

Google and Earthlink faced similar political problems in San Francisco when they offered to build out a city-wide WiFi network providing free service to everyone while offering a faster paid tier of service to subscribers. The WiFi network was proposed by mayor Gavin Newsom in 2004, but by 2007 San Francisco's Board of Supervisors had successfully waged a political war against the mayor to defeat any hope for a free municipal WiFi network. That same year, SNAFU even managed to get Board of Supervisors president Aaron Peskin to introduce legislation imposing a 45-day moratorium on microcell antennas throughout San Francisco.

In addition to radio antenna fear mongers, the Board's fight with the mayor over WiFi was joined by community activists who demanded free WiFi at full broadband speeds while also demanding twice the agreed upon contractual commitments from Google and Earthlink, and privacy advocates who assailed the city's contract for making "creepy" mentions of "the needs of law enforcement," allowing access to "lawful Internet content," and noting support for all "legal devices that do not harm the Network."

It also doesn't help that a free city-wide WiFi network in San Francisco would naturally be opposed by paid data service providers from Comcast to Verizon and, ironically, AT&T, which now has a pundit-heavy city of iPhone users who daily rant about the terrible cellular service it provides, while lacking any backup WiFi service that would have been provided by Google and Earthlink.