There's more than one way to disrupt a market's status quo, and all forms of disruption aren't equally valuable, as indicated by the value created by Apple's iPhone compared to Google's Android platform.

Source: Intercom

Is Google disrupting Apple's disruption?

Every startup and business initiative likes to describe itself as being "disruptive," that is, an interrupting force that changes the prevailing nature of a given industry, shifting the balance of power and the identity of those making the most money.

Apple's iPhone has, since its debut in 2007, had a spectacularly disruptive effect on not only the smartphone market, but has also disrupted the revenues of parallel standalone devices, ranging from personal cameras and camcorders to dedicated game consoles and GPS products.

Particularly since 2010, observers who formerly dismissed and underestimated the impact of the iPhone have now jumped to the conclusion that Google's Android will, is, or perhaps already has had a similarly disruptive effect on Apple's future prospects, acting as a disruptor of Apple's disruption.

However, as noted in a report by the developers of Intercom, there's more than one type of disruption, and all forms of disruption aren't equally valuable, important, or sustainable.

Differentiating disruption

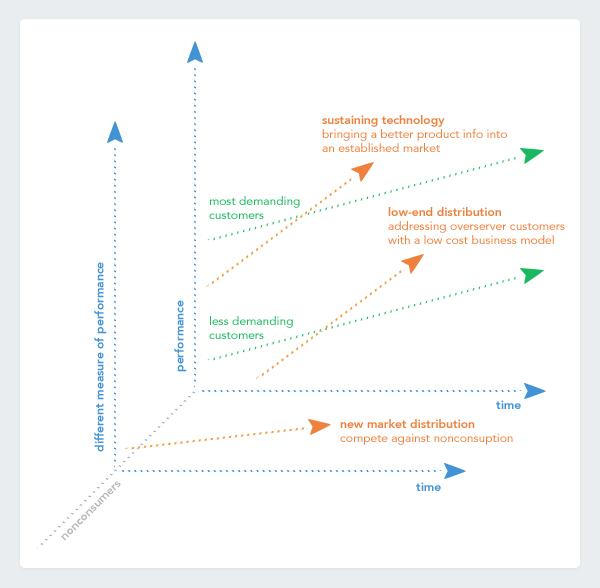

One form of disruption identified in the report is "new market disruption," which "competes against non-consumption." Essentially, this means bringing to market a new product that finds a new class of customers that weren't really being served by existing products.

In parallel, the report also describes the disruption of "sustaining technology," which it says involves "bringing a better product into an established market," where customers pay more to trade up to a premium product.

A third type of disruption is "low end distribution," which "addresses over-served customers with a low cost business model." In this form of disruption, customers who can get by with a cheaper alternative trade down to this new product to save money.

Apple has launched a series of products fitting all of these descriptions, creating entirely new markets that have also had a disruptive effect on existing industries, both with premium hardware and with lower cost software features that have eroded (or in some cases shattered) the profits supporting preexisting products.

Examples of different types of disruption

The iPod created a new volume of demand for premium music players, for example, one that really didn't exist before.

It initially appealed to the "most demanding customers," but newer, cheaper versions of iPod also undercut the low end of the market, reducing any pricing umbrella for Apple's competitors.

Together, those factors have enabled Apple to own the top, the middle and the bottom of the MP3 player business, and create the largest ecosystem of supporting content sales and related services around it with iTunes. Apple's global rollout of the iPhone hasn't yet addressed the low end of the market in the way the iPod mini and nano did.

The iPhone has also been disruptive on many levels. It initially introduced high-end smartphones to the mainstream to a new class of users. It also replaced existing leaders in the smartphone market (Nokia's Symbian, Palm, Microsoft's Windows Mobile and RIM's BlackBerry) with a better product.

However, Apple's global rollout of the iPhone hasn't yet addressed the low end of the market in the way the iPod mini and nano did.

Apple's cheapest iPhones are simply its older generations, and in this arena, Android licensees (along with other low end phones like select BlackBerry models and Nokia's S40-based Asha line of entry level phones) have taken more global market share, particularly in developing markets.

Grabbing the low end is easier, but not as valuable

While offering cheaper, low end smartphones is often also described as "disruption," the value of this "low end distribution" is clearly not as great as Apple's high end disruption, as evidenced by the fact that Apple earns so much more than the rest of the mobile industry combined.

At the same time, despite having ignored the bottom of the mobile phone market Apple has still managed to retain iPod-style ecosystem dominance over mobile apps and the usage stats that drive supporting accessory sales and specialty markets such as government, education and enterprise.

Taking over the low end of a market is a lot easier to do than attracting premium sales, as Apple demonstrated when it rapidly gobbled up the flash-based MP3 market with the iPod mini, in contrast to struggling efforts by the higher end Microsoft Zune and Samsung Galaxy Player to make any dent in Apple's premium iPod touch business.

Samsung is incessantly credited with "disrupting" the advance of Apple's iPhone and taking more market share via volume sales of lower end phone models. However, Apple could quite easily take the "market share trophy" simply by producing lots of low profit, low end phones and dumping them on the market.

However, doing that would make Apple much less profitable. Instead, Apple has targeted premium profitability, a strategy that has served it well over the past decade.

Samsung, Motorola, LG and other key Android licensees have also made shipping premium, higher end phones a priority. But as with the history of the iPod (mirrored in the PC world as well), Apple's competitors have found it a lot more difficult to take share in the lucrative high end than compete for the bottom.

This reality, which isn't really controversial at all, makes it particularly curious why the market is so enamored with smartphone market share (particularly when it comes through low value sales) rather than sustainable profitability.

It's as if everyone believes that the market for smartphones is going to work out completely different than the market for iPods and Macs and iPads, even though none of the available evidence (including profitability, ecosystem support, user preference and satisfaction) supports that idea.

Low end disruption isn't just less valuable, it's less sustainable

The vast resources at Apple's disposal make it obvious that, given the choice between earning profits and saturating the market with "device shipments" to gain market share, Apple is explicitly choosing to make money rather than to just set temporary sales records for the likes of IDC and Gartner.

Apple has the billions needed to manufacture profitless millions of iPhone 3GS units it could shove off the back end of cargo planes over India, Brazil, Africa and other regions where it would do little to threaten its existing iPhone sales, if the company simply wanted bragging rights to "market share shipments."

On top of that, in addition to being less profitable to aim for the bottom, such low end disruption is harder to sustain, particularly if the only factor in such disruption is low price. Just ask the world's former producers of netbooks (or cheap PCs of any form factor, for that matter). It's hard to survive in the cutthroat world at the bottom.

Flipping out of business

One example of the temporary nature of low end disruption cited in the report is Cisco's $590 million acquisition of Flip, which it described as once being the "darling of the camera industry" because its portable camcorders were a cheap, lower end alternative to more expensive camcorders, and subsequently appealed to lots of customers with basic video needs.

Unfortunately for Cisco, another low end disruption was also occurring: Apple's iPhone went from having no ability to record video to being a very competitive option for uses with simple needs. While even less powerful than some models of the Flip, smartphone camcorders were vastly more convenient because they didn't involve carrying another device.

Cisco's hopes to perpetuate Flip's success at tapping the bottom of the camcorder market collapsed because they were undermined by the ubiquity of even lower end disruption at the hands of smartphone video recording features.

Source: Flickr.com/cameras

Apple rapidly shifted from paying little attention to the original iPhone's camera to being the runaway market leader among cameras represented on sites like Flickr simply by incrementally improving the iPhone's camera and software.

Apple is also adept at low end disruption

While Apple hasn't yet decisively jumped into the low end of the smartphone pool with a cheap iPhone offering, it has ruthlessly undercut the bottom out of a variety of other markets, in some cases without even giving the appearance of trying.

In addition to Flip, the report drew particular attention to the collapse of GPS makers Garmin and TomTom, both of which saw their value evaporate once Apple's Maps app appeared. It didn't matter that Maps was less powerful than an standalone GPS.

Source: Google Finance

"In September 2007," the report noted, "[Garmin and TomTom] were worth a combined 38 billion dollars. A mere 12 months later, they weren’t even worth 8. What happened? The iPhone. A 38 billion dollar industry loses 3/4 of its market cap in a year because someone decide to add a maps app to the home screen."

Apple's iPhone has similarly eviscerated a series of other once important markets, including handheld video games. That's something Apple clearly didn't set out to do, but it happened anyway. And again, it occured without regard for the fact that dedicated games were more powerful and compelling than most iOS games.

It's worth noting that while the iPhone quickly sucked the life out of the older Nintendo DS and Sony PSP platforms that arrived a few years before it, new generations of those devices haven't had much success in winning back sales.

Clearly, it's much easier for a premium device to cut the bottom out of competitors' higher end offerings than it is for specialty, premium devices to compete against a device that serves as a hybrid disruptor, adept at both premium upselling and low end disruption at the same time.

Low end disruption is not disrupting Apple

At the same time, cheaper low end disruption by Android handsets hasn't had any discernible impact on Apple's App Store leadership. The only real software exclusive Android has cornered the market on is malware.

Google's platform hosts 97 percent of the discovered signatures of circulating mobile malware, according to McAfee. Google's platform hosts 97 percent of the discovered signatures of circulating mobile malware.

Outside of malware, the edge in market share claimed by the world's various Android licensees as a collective has not achieved the critical mass needed to blunt the development of iOS software or restrict the availability of sources of media content the way that Microsoft's overwhelming dominance in PC market share with Windows once had on the Mac platform.

In fact, the reality that Apple battled the Mac OS X platform back into relevance against the ubiquity of Windows PCs, starting with a market share around 2 percent and making gains in excess of ten percent of the current market tells you something about the weakness of the threat Android poses to iOS going forward: Apple remained highly profitable even with minority Mac market share; the majority of Android licensees are not, despite their collectively dominant share.

Low end disruption by iPad

Additionally, while Apple kept the Mac a healthy platform in the face of overwhelming low end disruption by budget PCs and netbooks, it was also able to rapidly slash the bottom of the PC market wide open with the release of the iPad three years ago.

iPad sales have, like the iPhone and iPod before it, competed as both high end premium alternatives that are attractive to "the most demanding customers" while at the same time offering software functionality that serves as low end disruptors.

Of particular interest to the enterprise, for example, is the fact that the iPad is cheaper to administer and maintain than more complex PC alternatives such as notebooks, netbooks, slate devices or Microsoft's curious Surface.

The iPad effectively delivers the utility of the PC in providing simple features (browsing the web, accessing email, consulting web services and corporate data) without the complexity or expense of maintaining a Windows desktop.

Despite two years of monumental efforts by the combined resources of Apple's global competitors, nobody has delivered a tablet that has challenged Apple's position. There are cheaper tablets, but they aren't gaining traction in high value markets, and they aren't sold at a sustainable profit because Apple's iPad prices are too competitive.

Apple will continue to disrupt smartphone sales

That fact should provide some clue to the future of the mobile industry as two situations continue to occur: first, Apple continues to gain ground in carrier distribution.

A major reason why Apple has less market share among smartphones than in music players and tablets is simply due to the fact that Apple has historically had far fewer points of distribution than the entrenched mobile manufacturers that existed before the iPhone.

That's not the case in the non-phone world, where Apple has stronger distribution for its computers, tablets and music players than most of its competitors, a fact that's reflected in its stronger sales.

Note too that in addition to carrier availability, rival smartphones have been losing exclusive features to the iPhone at a rapid pace: camcorder features, MMS, multicore chips, LTE and so on with each new iPhone generation. Yet as Apple's phone gets stronger and the competition loses ground, critics wail about it "not being able to keep up," pure flawgic.

A second shift that appears certain to occur sooner than later is that Apple will increasingly begin to aggressively address the low end of the smartphone market.

Apple hasn't entirely ignored this segment; each new iPhone release has been accompanied by lower cost versions of previous generations, reaching the point where the company finally began offering a "free with contract" iPhone for the first time just a year and a half ago.

Analysts who are banging the drum that Apple desperately needs a cheap iPhone are forgetting that the company has been working in that direction for a long time.

More importantly, it's not a goal that needs to be reached in an emergency, because taking the low end is quite easy for anyone who already has the top of the market under control, as Apple demonstrated with the iPod and again with iPad.

When Apple failed at distruption: a lesson for Android

There's one further example of the difficulty of disrupting from the bottom: it comes from Apple itself.

When the company tried to break into the enterprise server and storage market with the 2005 Xserve and Xserve RAID, it attempted to leverage its Mac OS X Server platform to deliver equipment that could rival the higher end offerings of rack mounted server room equipment.

Apple hoped to undercut established PC server vendors, including Dell and HP, by offering a server package that delivered comparable hardware with vastly cheaper software than Windows Server, resulting in a much lower price overall.

Apple's OS X Server software was essentially free with new hardware (just like Android!), compared with Microsoft's per-user licensed services that, in effect, amounted to greater expense for enterprise users than the server hardware itself.

Xserve RAID also attempted to undercut alternative Network Attached Storage devices by offering cheaper disk subsystems, providing comparable utility at much lower prices (just like Android!)

Apple's Xserve never established much of a market for itself, in part because the company lacked the hands on support services that enterprise-savvy vendors like Dell provided to their satisfied customers (just like Android!).

XServe RAID was canceled even earlier because the NAS market wasn't at all impressed by lower prices; they preferred the assurance of acquiring drives rated for true enterprise duty, rather than the consumer-class disks Apple was trying to sell them as cheaper and "good enough."

The logic supporting Android's eventual domination of smartphones through cheaper, lower end hardware paired with with less friendly end user support and less sophisticated, but much cheaper software is soundly refuted by the results of Apple's own failed attempts to enter the server room through the bottom of the market.

Apple hasn't repeated the same mistake in any of its other hardware categories. Conversely, there aren't any Android licensees that are successfully rivaling Apple on the high end. That draws a very close parallel between Android's future prospects and Apple's singular high profile failure to disrupt a major new market over the past decade.