The iPhone Patent Wars have now been raging for nearly four years, not in the competitive market for smartphone sales, but rather in contentions over intellectual property, expressed in the government-enforced monopolies over inventions known as patents.

These wars have been waged in the courts over damages related to patent infringement, within private negotiations for settlement and in Executive Branch decisions considered by the International Trade Commission, a quasi-judicial federal agency with the power to block imports and ban sales. ITC bans are a particularly devastating weapon for patent holders to wield.One of the biggest Federal Court trials yet isn't even set to begin until next summer

One of the biggest Federal Court trials yet isn't even set to begin until next summer: a second case between Apple and Samsung following the original trial that resulted in a jury award of $1 billion in damages for Apple last fall. That case is still on appeal, too.

This series provides a look at what's happened so far, and why many in the general public aren't even aware of the extent and intrigue in the patent shenanigans occurring among Big Phone players, starting with how Apple got its reputation for abusing patents even before the iPhone appeared.

Apple becomes one of the most sued companies on earth

In 1985, there were fewer than 2,000 computing-related patents granted in the US. But by 2006 there were over 150,000 in effect, and over 17,000 more were being granted every year in the U.S. alone. Patents were not just being granted; they were increasing being leveraged to extract millions of dollars up front and in demands for ongoing royalty fees.

As the once beleaguered Apple Computer transitioned itself into the very successful Apple, Inc., a metamorphosis fueled by profitable sales of tens of millions of iPods in the first half of the 2000s, existing companies that failed to successfully compete in the market (or simply didn't bother to try) turned to patent litigation in order claim a cut of Apple's earnings.

Source: AAD Patent

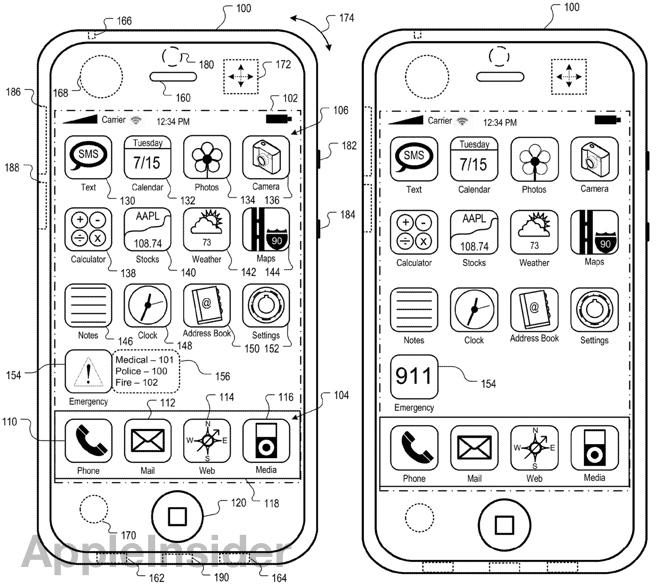

In March 2005, Advanced Audio Devices sued Apple over patent 6,587,403 for a "music jukebox," presented above from the patent filing as "a perspective view of a music jukebox in accordance with an embodiment of the present invention." Apple denied any infringement but eventually settled over an "undisclosed" sum.

The U.S. government, through the Patent Office, had in August 2000 granted Advanced Audio Devices "inventors" Peter and Michael Kelley a legal monopoly over the "invention" of a music jukebox that could play songs in playlists.

Using the legal system, the "inventors" demanded royalties from Apple to "practice this invention" four years after the company had invested millions into designing the iPod and building a viable business around it in a competitive marketplace where other companies were seeking to do the same, generally without being able to turn a profit.

The Contois and Creative monopolies on ordered lists and menus

In June 2005, Contois Music Technology sued Apple over patent 5,864,868, alleging that iTunes infringed upon its "Computer Control System and User Interface for Media Playing Devices," depicted below. The firm also sued Sony, Napster, Real and MusicMatch over the same patent.

Source: Contois Music Patent

A year later, in May 2006, Singapore-based Creative Technology sued Apple in court for damages over its "Zen patent" 6,928,433, officially titled "automatic hierarchical categorization of music by metadata," concerning the presentation of menus on a portable music player based on song metadata.

Source: Creative Zen Patent

In parallel, Creative also filed an injunction with the ITC seeking to ban imports of Apple's iPods. Apple countersued with patent claims of its own. Just three months later, the two companies settled out of court, with Apple agreeing to pay Creative $100 million and Creative joining Apple's "Made for iPod" licensing program.

Apple and the Billion Dollar Patent

That same month, Apple also settled with Contois, buying the disputed patent for an "undisclosed" sum. Michael Starkweather, the lawyer of the patent's inventor, later issued a press release describing the patent as being worth a billion dollars and predicting that Apple would use it to shake down the entire industry for royalties.

"I believe that, with this patent in hand," he stated in 2006, "Apple will eventually be after every phone company, film maker, computer maker and video producer to pay royalties on every download of not just music but also movies and videos.""Apple will eventually be after every phone company, film maker, computer maker and video producer to pay royalties on every download"

That never happened however. Apple didn't exercise its supposed "billion dollar patent" in a royalty offensive designed to syphon off the profits earned by the rest of the industry.

Instead, it essentially buried the patent, preventing Contois itself from suing "every phone company, film maker, computer maker and video producer" on earth, including Apple's customers, its partners and its competitors.

However, new companies continued to come out of the woodwork, all demanding from Apple millions in royalties of their own related to dubious patent claims. Note that in addition to the major cases above, there were lots of smaller claims and suits targeting technologies in Apple's Macs and other devices and peripherals, including the Nike+iPod pedometer sensor.

The Burst bubble in the iPod patent offensive

One of the most famous was Burst.com (the Burst.com domain is now operated by a different company) which had been suing Microsoft, then the world's leading technology company, for years over four patents related to "fast start" video streaming; essentially, buffering.

In 2005, after three years of legal wrangling, Microsoft settled with Burst, agreeing to pay $60 million to license its patent portfolio.

Burst planned to leverage its winnings in the patent lottery against Apple, hoping to claim, according to a report by BusinessWeek, a 2 percent cut of Apple's revenues related in any way to media playback, reaching in the ballpark of $200 million.

Burst's threats loomed just as patent holding "Non Practicing Entity" NTP, Inc. had successfully won a jury award against Blackberry maker RIM for $33 million, an amount the judge punitively increased to $53 million for being "willful," along with ordering an injunction that would not only block Blackberry sales but turn off the company's core messaging network that served RIM's installed base of subscribers.

Fed up with the flood of shameless patent extortion going on, Apple fired the first shot against Burst.

That promised to not just drive RIM out of business, but also be so disruptive to critical U.S. government operations that the U.S. Department of Justice and Department of Defense intervened to stop the injunction.

The case was eventually settled in early 2006 for $612.5 million, a number considered low by some observers because it stopped NTP from claiming any future, ongoing rights to additional patent royalties.

Fed up with the flood of shameless patent extortion going on, Apple fired the first shot against Burst in early 2006, filing a lawsuit seeking to invalidate the Non Practicing Entity's entire patent portfolio. Burst then filed suit against Apple for infringements of 36 claims related to its four patents, just over a year after it first began asking Apple for money.

After Apple was successful in getting 14 of the claims on the patents tossed out, Burst agreed to a settlement in November 2007 that for "only" $10 million ended all of Burst's future and ongoing claims.

Apple gets maligned for fighting back

Much of the coverage of Burst's lawsuit against Apple flowed from columnist Mark Stephens, writing under the name Robert X. Cringely for a variety of sources, including "I, Cringely" for PBS.

Source: PBS

In January 2006, he described the preemptive strike as "an enormous mistake for Apple," noting that "since Apple sued Burst, Burst shares have gone UP by 30 percent. The market is rarely wrong," he explained.

He continued by predicting, "Apple will lose and Burst will win, and Apple won't be able to afford to wait for the courts to decide anything."

By September 2007, "I, Cringely" was complaining under the curious headline, "I Report, You Decide: Patent cases like Apple v. Burst.com deserve better news coverage," that "there has been a heck of a lot of spinning going on having to do with a story I broke years ago and have followed off and on ever since -- the trials of little Burst.com -- and even the revered New York Times (and nearly everyone else) this time got it shamefully wrong."

He linked to what he called "an especially deplorable story in Ars Technica," which had summarized the case in the sentence, "a tiny firm with a few patents is trying to get some big bucks from Apple in licensing fees," stating that "Apple looks to be taking a stand" and that "other patent trolls may want to take some notes."

At that point, Burst was now gunning for $500 million from Apple, of which Cringely noted, "that's a lot more than the $60 million Burst got from Microsoft and for a good reason: Microsoft generally gave away the technology they stole from Burst while Apple sells it."

What did Apple "steal" from Burst?

Burst's patent 4,963,995 from 1990 and 5,164,839 from 1991 describe compressing video and sending it over a network for faster than real time remote playback "from one video tape to another using only a single tape deck."

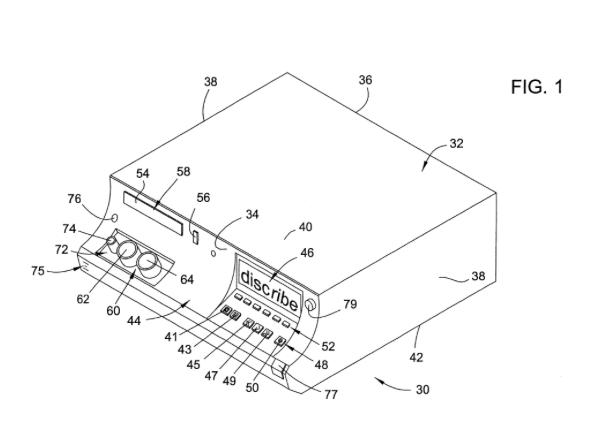

Patents 5,057,932 from 1991 and 5,995,705 from 1999 describe a digital VCR-ET ("editor/transceiver," pictured below) with the ability to store, edit and transmit recorded videos to another VCR-ET.

Source: Burst Patent

With these patents, Burst was alleging broad infringement involving "the iTunes Store, iPod devices, iTunes software, iLife software (GarageBand, iMovie, iWeb) separately and in conjunction with the .Mac service and Apple computers sold with or running iTunes or iLife," essentially everything Apple sold at the time.

Cringely was more than a little sympathetic to Burst, which he noted "is a three-person company based in Santa Rosa, CA, where I used to live" and which at the time had "almost no sales."

However, he added that "Burst's technology was developed over a period of 20 years by far more than three people at a cost in excess of $66 million," complaining that "the implication in many of these stories is that Burst cobbled together some dubious patents and tried to coerce real companies into taking licenses, that they are so-called 'patent trolls.' Trolls don't spend 20 years and $66 million building the bridges they defend."

Two years of writing patents, ten years of failed sales, five years of suing

But neither did Burst. According to the LinkedIn profile of Burst (now known as Democrasoft) inventor/patent holder Richard Lang, he "co-founded this company with Lisa Walters in 1989. Went on to develop, patent and introduce burst-mode (faster-than-real-time) media delivery to optimize quality, reliability and user experience of video & audio over networks. Developed portfolio of U.S. & international patents. Company became public in 1992."

Source: Richard Lang, LinkedIn

Three quarters of Lang's "patent portfolio" asserted against Apple in 2006 were filed between 1990 and 1991, just a year or two after he founded Burst. The company subsequently tried to set itself up as a proprietary toll link between consumers and video streamers, but after failing to sell its ideas to Microsoft, Burst turned into a litigation company in 2002, and after three years of suing Microsoft, spent two years suing Apple.

Burst had demonstrated a digital streaming prototype VCR in 1991, but wasn't able to develop, produce or market a successful product. Using the patent system, it hoped to gain a monopoly over the entire concept of streaming digital video, long before the idea was really practical.This kind of use of the patent system and the courts doesn't have much in common with Apple's attempts to stop Samsung.

Using the legal system, Burst then began to retroactively "sell" other companies the right to have implemented their own technology for a fee in the millions of dollars, with negotiations that began only after those other companies had finished their products and gainfully sold them for half a decade.

Of the $10 million settlement Burst finally negotiated with Apple, $5.4 million went to the company's attorneys and legal fees, not to an inventor. The rest appeared to be largely paid to the firm's shareholders as a dividend.

This kind of use of the patent system and the courts doesn't have much in common with Apple's attempts to stop Samsung, for example, from selling virtually identical products to the iPhone and iPad in an obvious, immediate response to Apple's products selling and Samsung's not being nearly as successful.

Overwhelmingly however, virtually all reports of patent infringement are presented by journalists with a presumption of guilt. Once "infringement" of a patent is alleged, the question is rarely "is the patent legitimate?" or "does this product actually infringe valuable intellectual property?" but rather "how many millions will this company need to pay?"

Apple shifts patent target from iPod to iPhone

Apple's efforts to quickly settle the various iPod-related patent lawsuits being waged against it in 2006 seems, in retrospect, to have been part of an effort to get past the litigation in order to focus on its innovative new iPhone that was due for introduction in 2007.

After having survived a barrage of patent attacks on the iPod and iTunes (among those also targeting its other products), Apple's chief executive Steve Jobs expressly noted at the iPhone's introduction that the company had patented every aspect of its new mobile phone that it could, in order to protect itself from having its own work taken.

However, just as Apple never threatened to use its supposed "billion dollar patent" on the rest of the industry, it also didn't begin arming its iPhone patent missiles for launch until 2010, three years deep into the iPhone's existence.

Major smartphone vendors watching their sales collapse were more than willing to resort to legal action, however, as a future segment in the iPhone IP Wars will outline. The next segment focuses on Apple's shifting role as a litigator and as an innovator in the intellectual property wars that birthed the current world of patent conflicts, looking at the computing world before patents were in widespread use.