Understanding Apple's intent to patent every valuable aspect of the intellectual property that went into creating iPhone in 2007 requires a look at what happened a quarter of a century earlier in the development of Apple's Macintosh.

After two particularly intense years of patent lawsuits between 2005-2007, headlined by the four outrageous patents detailed earlier, Apple announced the iPhone, emphasizing that virtually every significant aspect of its entirely new experience and industrial design was protected by patents. It wasn't until nearly three years later that a global patent war erupted.

Apple as an early innovator

When Steve Jobs returned to Apple in 1997, one of his priorities was to get Apple out of its legal skirmishes with Microsoft. Starting in the late 1980s (after Jobs had left), Apple had turned to the legal system in an attempt to stop Microsoft from appropriating the Macintosh user experience that Apple had developed over the previous decade. Rather than litigate, Jobs sought to restore Apple to former identity as an innovator.

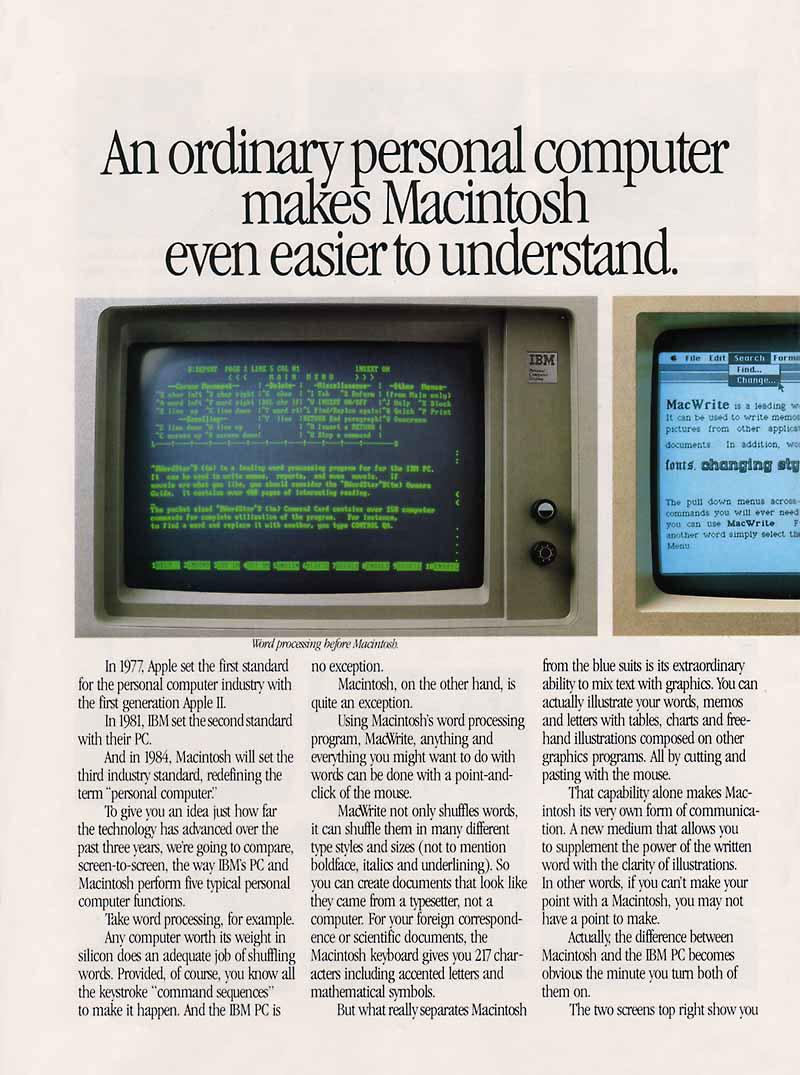

At the time that Apple began work on the industry-changing Macintosh in the early 1980s, IBM-compatible PCs of the day used Microsoft's MS-DOS to run "programs," also known as "executables," creating "subdirectories" of "files."

Every program used its own custom routines for talking to printers and for adding control codes that would, for example, configure a portion of text in a file to print out in boldface. Each also presented its own unique set of keyboard commands to trigger saving or printing a file.

For example, to open an existing file in WordPerfect (shown above in an Apple ad that appeared in Newsweek in 1984), you'd use the command F7 + 3. But WordStar used Ctrl + K + O, and in Lotus 1-2-3 you'd type / to open the menu, W for Workspace + R for Retrieve. In Microsoft Word you'd type Esc to open the menu, T for Transfer + L for Load.

Using a computer involved learning how to use a computer, and then learning how to use each program, individually.

Xerox the duplicator

Apple, flush with profits from successfully building computers in the late 1970s, had started work on advanced projects intended to greatly advance computing and make its systems accessible to a broader, mainstream audience, with graphical screens capable of depicting different font faces, rather than just a character grid of monospaced text.

While popular legend says that Apple simply got its Macintosh ideas from the Xerox Palo Alto Research Center after seeing the group's advanced technology in 1979, this isn't the case.

Throughout the 1970s, Xerox had worked on an advanced, $16,000 Alto workstation prototype (above, displaying its FileManager interface; below, graphical menu buttons) that as part of an overall package (including networked laser printing and a file server) started at around $75,000. When it tried to bring its own Star successor workstations to market in 1981, it failed.

Technologies invented at PARC were rapidly flowing out of Xerox and founding entire new businesses, including 3Com, co-founded in 1979 by PARC's Robert Metcalfe to commercialize its Ethernet networking, and Adobe, founded in 1982 by PARC's John Warnock and Charles Geschke to develop PostScript from the InterPress research Xerox wasn't interested in pursuing on its own.

Microsoft hired PARC's Charles Simonyi in 1981 to port the Alto's Bravo word processing software to other personal computer platforms under the name Microsoft Word.

Xerox willingly invited Apple representatives to visit its PARC think tank after signing an agreement that invested $1 million into the computer maker in the hopes that Apple could take PARC's raw technologies and make them commercially successful in the consumer market, using mass manufacturing, product development and marketing expertise that the academic computer scientists and engineers at Xerox lacked.

Engineering a better mouse

For example, central to Xerox' windowing interface was the "mouse" input device, originally conceived by pioneering computer scientist Douglas Engelbart in the 1960s and further refined by Xerox in the 1970s. However, it was Apple that developed the first version of the mouse that consumers would recognize.

Apple quite literally could not just "steal" Xerox's mouse because there wasn't enough there to even sell. Apple had to develop the technology to make it commercially successful. This was not a simple matter; it involved an interplay of expertise nobody else had achieved, despite the concept having been publicly demonstrated since 1968.

Source: Dean Hovey

Apple's Jobs tasked Dean Hovey's industrial-design firm, as reported Malcolm Gladwell of the The New Yorker, with converting Xerox's three button device, "a mouse that cost three hundred dollars to build and it breaks within two weeks," to Jobs' design spec: "our mouse needs to be manufacturable for less than fifteen bucks. It needs to not fail for a couple of years, and I want to be able to use it on Formica and my bluejeans."

When Apple introduced its Macintosh mouse in 1984, it was such a novel breakthrough that PC columnist John Dvorak wrote, in a review for The San Francisco Examiner, "the Macintosh uses an experimental pointing device called a mouse. There is no evidence that people want to use these things. I dont want one of these new fangled devices."

Apple's mouse and its related developments would subsequently go on to dominate computing for the next two decades. In fact, 23 years later, a mouse would empower Dvorak to publish another opinion, this time advising Apple to "pull the plug on the iPhone," because "there is no likelihood that Apple can be successful in a business this competitive."

Publishing desktop

Apple needed more than just an affordable and reliable mouse however. It needed to create a graphical user environment that could interact with it to accomplish valuable tasks for users and make computing accessible to ordinary people without a particular interest in technology.

As part of its vast development work on what would become Lisa and then Macintosh, Apple employed hardware and software engineers (including many recruited from PARC) along with artists, designers and marketing experts to develop not just a computer and operating system software, but also an entirely new "desktop" user environment that coined user-friendly new terms for existing, techy computing concepts.

On the Macintosh, executable programs were called "applications," while files became "documents" organized into "folders." Along with building a workable mouse, Apple also coined terminology for using it, including "clicking" and "dragging" on icons, ideas that were so novel they required instructions on how to use these new "techniques" (below, an original Macintosh manual captured by Peter Merholz).

Apple also created standards governing every facet of the user interface, from new "dialog boxes" used to open, print and save documents the same way in every application; to new windowing controls; to graphical representations of disks, apps and docs known as "icons" in an allusion to religious imagery. All of these ideas were codified in Apple's exhaustive library known as the Macintosh Human Interface Guidelines.

The OG HIG

The Mac HIG focused on making everything standardized to the point where it became possible for even small developers to create applications that could be used by people with various types of disabilities, and localized for use in other languages and cultures. In both cases, third party developers could leverage the accessibility and localization experts Apple had hired to create system wide support for entirely new operating system concepts.

Source: Apple HIG

Apple's HIG also insisted upon developers approaching esthetic appearance as a component of functional design, and introduced minimum standards related to computing behaviors, such as the ability to globally "undo" an action performed by mistake, or the stipulation that users shouldn't be presented with frustrating options they can't actually choose.

Source: Apple HIG

Apple also developed a standardized set of keyboard shortcuts that were intended to work across every application, so users wouldn't have to learn one set of commands for printing or copying and pasting text within WordPerfect word processing, then switch to an entirely different set for Lotus 1-2-3 spreadsheets, and so on across every program they used. In every Mac application, for example, Command + P was used to print, + O to open, + Z to undo and + Q to quit an application.

Apple also introduced the concept of system wide "cut, copy and paste" for selecting text and graphics in one document and moving it into another application, a concept so novel at the time that the company had to explain how it worked in its marketing materials.

Source: Computer History Archive

None of these concepts had originated at Xerox. Apple had also developed the original menu bar and the pull down menu, along with guidelines describing in detail how each should work. One example of this was pioneering and consistently enforcing the idea of "direct manipulation," where users clicked to select an icon and then dragged it into a folder to move its location.

On Xerox's Alto, clicking on graphic representations on the desktop simply resulted in a popup menu of choices. You couldn't drag icons around. Apple's draggable "trash can" and the idea of pulling on the corner of a window to resize it are other examples of Apple's direct manipulation invention.None of these concepts had originated at Xerox.

"The difference between direct and indirect manipulationbetween three buttons and one button, three hundred dollars and fifteen dollars, and a roller ball supported by ball bearings and a free-rolling ballis not trivial," wrote Gladwell. "It is the difference between something intended for experts, which is what Xerox PARC had in mind, and something thats appropriate for a mass audience, which is what Apple had in mind."

Contrast the roughly $60 million ($170 million in today's dollars) Apple reportedly invested into developing the original Lisa, along with the tens of millions in research and development that went into years of further ongoing work and logistics in building and marketing the Macintosh, with the series of multimillion dollar patent claims brought against iPod around 2005 based on somebody drawing a picture of an interface of menus.

The Macintosh duplicator

Just as Xerox had invited Apple to help it bring its raw, high end business technology to consumers, Jobs invited Bill Gates of Microsoft (then struggling to enter the market for business programs on its own DOS platform) to become a new developer of Mac office applications, exempt from facing any of the first party competition Apple had earlier introduced for its Lisa computer with Lisa Office.

Despite having hired Simonyi from Xerox PARC in 1981 to resell the Alto's Bravo word processor, Microsoft Word faced tough competition on the DOS PC from WordPerfect. Simonyi's team also wrote a clone of the VisiCalc spreadsheet named Multiplan (later Excel), but it similarly faced a difficult barrier to entry on DOS PCs because of the popularity of Lotus 1-2-3.

Jobs presented the Mac as a wide open opportunity for both applications, and Apple promoted Gates' new Microsoft apps next to Mitch Kapor of Lotus Development and Fred Gibbons of the company developing pfs: database (below) as reasons for considering a Macintosh.

Microsoft ported Word and Multiplan to the Mac's graphical new environment, then later acquired third party Mac application PowerPoint in order to create the Macintosh Office suite, software which gave the company its first big break into the applications business, an important expansion outside of its core MS-DOS licensing program.

Gates also realized the potential for selling Apple's Macintosh user interface on IBM's PC hardware. He was not alone. Digital Research, Hewlett-Packard and Xerox PARC itself were also eying to enter this market. After failing to sell its Star workstations, Xerox later attempted to port its Star operating environment as PC software under the name GlobalView (below).

Xerox debuted GlobalView with windows and icons that looked similar to the Mac, but its windows couldn't overlap and its icons couldn't be directly manipulated. While its own Star and GlobalView products were failures, Xerox' initial $1 million investment in Apple to commercialize its PARC technologies grew in value to $17 million at Apple's IPO. Had Xerox held its Apple shares, they would today be worth over $2.1 billion, even without considering dividend reinvestment.

Microsoft's own parallel efforts to take Apple's Macintosh work and apply it to the PC resulted in a series of very rough "Windows" releases that similarly lacked the ability to overlap multiple windows on the desktop for years following the release of Macintosh.

Steve Ballmer touts features of Windows 1.0 in 1986

In 1986, Steve Ballmer outlined features of Windows 1.0 in an internal video (above) that referred to the DOS shell as an "advanced operating environment" and took credit for the system-wide copy and paste features Apple had introduced on the Macintosh two years earlier.

In December 1987, Windows 2.0 (below right) added support for displaying overlapping document windows and included for the first time the ability to run graphical versions of Word and Excel, ported from the Macintosh.

Windows 1.0, released November 20, 1985 (left) and Windows 2.0, released December 9, 1987 (right)

After five years of attempts that gained virtually no traction, in 1990 Microsoft launched Windows 3.0 and finally convinced PC makers to start pre-installing it on their new systems, expressly with the intent of allowing them to compete against Apple's Macintosh hardware, an aim very similar to Google's Android platform today.

Windows 3.0, released May 22, 1990 (left) and Windows 3.11, released December 31, 1993 (right).

Microsoft's difficulty in struggling for years to simply copy the Macintosh interface, seven years after Apple had launched the product (and despite having early access to Apple prototypes as a partner dating back to 1982, and enjoying parallel access to Xerox PARC) demonstrates how inarguably original and innovative the Macintosh actually was.

Lack of Macintosh patents gave Microsoft free rein to copy

Neither Xerox nor Apple had patented any novel aspects of the Alto, Star or Macintosh because nobody foresaw the need to patent anything within the new field of graphical user interfaces in personal computing.

Microsoft's Windows 2.0 appropriated much of the functionality of the Macintosh, introducing only trivial changes like renaming the trash can and locating the menu bar within windows (as MIT's X Window for Unix had). Unlike Apple's significant consumer-oriented technical and conceptual advancements of Xerox's original work, Windows was simply a blatant knockoff of the Macintosh that represented very little innovation. Windows was simply a blatant knockoff of the Macintosh that represented very little innovation.

Apple did claim copyright infringement over aspects of the Macintosh "look and feel," however. In 1988, largely in response to Windows 2.0, Apple successfully stopped other Windows-like PC competitors, including DRI and HP, who were both selling software with similarities to Apple's graphical user interface.

However, in 1985 Gates had secured a licensing contract with Apple's chief executive John Scully to use some Macintosh concepts ("visual displays") in Windows 1.0 in exchange for committing to exclusively deliver Excel for Macintosh.

The courts broadly interpreted this in 1992 and again on appeal in 1994, giving Microsoft (in its own expressed opinion) virtually unrestricted rights to duplicate the rest of Apple's work.

Xerox also tried to initiate copyright claims of its own against Apple, but it didn't start until December 1989. Its claims were thrown out for having exceeded the statute of limitations. Xerox stated that it wanted to broadly license user interface concepts to encourage industry standards in user environment design.

Windows 95, released Aug 24, 1995 (left) and Windows 98, released Jun 25, 1998 (right).

By late 1995, Microsoft was ready with Windows 95 (above), a new version of DOS hosting a graphical user environment that copied the Mac's look, feel, gestures, behaviors, keyboard shortcuts, terminology and even its human interface guidelines so closely that few people were even aware that virtually none of it actually originated at Microsoft.

Bill Gates, John Sculley and the Xerox-Macintosh myth

Seeking to minimize his blatant appropriation of Apple's Macintosh at Microsoft, Gates helped to promote the popular legend that the Macintosh was largely just a rewarming of Xerox's technology on the same level of his own acquisition of Word, epitomized in his famous quote"we both had this rich neighbor named Xerox and I broke into his house to steal the TV set and found out that you had already stolen it.""We both had this rich neighbor named Xerox and I broke into his house to steal the TV set and found out that you had already stolen it." - Bill Gates

Scully's 1987 book Odyssey also strongly implied this. Sculley wrote that "much of the Macintosh technology wasn't invented in the building,'' and stated, ''indeed, the Mac, like the Lisa before it, was largely a conduit for technology developed" by Xerox at PARC.

However, Sculley wasn't even hired by Jobs to run Apple until April 1983, four years into the development of the "Lisa Desktop" and just 8 months before the Macintosh actually went on sale.

Sculley's ill-considered 1985 licensing agreement, which essentially handed all of Apple's Macintosh development work to Microsoft in exchange for a brief commitment by Microsoft to support Office, offered a strong motivation for him to minimize the severity of his blunder and its consequences for Apple.

At the same time, Sculley also presided over Apple's late 80s partnership with Olivetti (the Italian owner of British PC maker Acorn) that culminated in plans to jointly develop a new mobile processor architecture capable of powering Sculley's pet project: the Newton Message Pad (below).

While that early tablet was ultimately much less successful than anticipated, the ARM partnership developed the mobile processor technology Apple later used to power its iPod, and continues to serve as the core of Apple's A6 and related chips powering the iPhone and iPad.

Additionally, the dramatic appreciation of Apple's 47 percent ownership stake in ARM, fueled by the overwhelming popularity of the chip architecture in embedded devices and mobile phones, later provided Jobs with the liquid assets he desperately needed to finance Apple's turnaround in the late 1990s.

Microsoft sets out to kill Macintosh, saved by Jobs' return

After directly and willfully copying Apple's years of non-patented efforts on the Macintosh, minimizing the work Apple had done and implying that it had simply stolen the Macintosh from Xerox, Microsoft, led by Gates and its current chief executive Steve Ballmer, next set out destroy Apple and take all of its business.

Microsoft effectively stopped development of its Macintosh Office software and focused its efforts on enhancing its applications for Windows instead. At the same time, Microsoft also began copying Apple's new QuickTime architecture (below) for digital video and media, first released in 1991.

Microsoft initially announced "Video for Windows" in 1992, followed by ActiveMovie vaporware that was supposed to compete with what Apple was shipping; much of this promised software never actually materialized. The media, however, frequently described Microsoft's vaporware as if it were real and reviewed what Microsoft was promising against the finished work Apple was trying to sell.

When Microsoft ran into problems duplicating Apple's QuickTime work conceptually, it used San Francisco Canyon Company, a third party developer Apple had contracted with, to gain access to Apple's QuickTime for Windows code in order to improve its own Video for Windows product. When it got caught, it complained that the issue was blown out of proportion and minimized the amount of code it had stolen.Apple had Microsoft's fingerprints on a smoking gun and was prepared to sue the company for hundreds of millions of its own over intellectual property theft.

Apple filed suit in 1994, and won a restraining order in 1995 that stopped Microsoft from distributing the stolen code.

By 1996, Microsoft had already paid out hundreds of millions of dollars in settlements related to legal complaints of other anti-competitive activities, including similar instances of direct code theft from its competitors and partners.

In the San Francisco Canyon case, testimony that later surfaced in the Microsoft Monopoly trial showed that Apple had Microsoft's fingerprints on a smoking gun and was prepared to sue the company for hundreds of millions of its own over intellectual property theft.

Apple also threatened to bring dozens cases of patent infringement related to operating system and web browser technologies, based on the growing portfolio of patents Apple had been amassing since losing its "look and feel" copyright case.

However, freshly back at Apple in 1997, Jobs immediately set out to turn the company around and begin building innovative products again, rather than just converting Apple into a Non Practicing Entity focused on litigation the way many of Microsoft's other victims had, most notoriously Caldera, later known as SCO.

Back to the Mac

Jobs addressed Apple's third party developers in August 1997 with plans to work with, rather than against, Microsoft, an idea that actually elicited boos from his audience.

However, Jobs focused on the need to move Apple ahead, outlining plans that required Microsoft to provide a two part demonstration of its investment in the future of Apple: an infusion of $150 million cash (an investment Microsoft subsequently profited from) and a commitment to maintain new versions of Office for Macintosh for five years. Apple settled its patent infringement and civil damages claims against Microsoft, reported by Computerworld at the time to be worth at least $1.2 billion.

In return, Apple settled its patent infringement and civil damages claims against Microsoft, reported by Computerworld at the time to be worth at least $1.2 billion, and designated Microsoft's Internet Explorer as the default, but not exclusive, web browser on the Mac.

By portraying Microsoft as a friendly partner and investor, rather than a litigation defendant and general enemy, Jobs was able focus more attention on making Apple competitive.

Four years later, Apple had recovered to the point of introducing the first release of its own innovative new operating system, the first successful new mainstream personal computing platform since Windows itself, and iPod, a product that rapidly became so successful it turned Apple itself into a target of patent litigation.

Mac OS X 10.0 "Cheetah," released Mar 24, 2001 (left) and Mac OS X 10.1 "Puma," released Sep 25, 2001 (right).

Mac OS X 10.2 "Jaguar," released Aug 23, 2002 (left) and Mac OS X 10.3 "Panther," released Oct 23, 2003 (right).

Mac OS X 10.4 "Tiger," released Apr 29, 2005 (left) and Mac OS X 10.5 "Leopard," released Oct 26, 2007 (right).

Mac OS X 10.6 "Snow Leopard," released Aug 28, 2009 (left) and Mac OS X 10.7 "Lion," released July 20, 2011 (right).

Mac OS X 10.8 "Mountain Lion," released July 25, 2012 (left) and Mac OS X 10.9 "Mavericks," expected Oct 2013 (right).

By focusing on innovation, rather than dwelling on litigation, Apple's Jobs kicked off a decade of work that soundly defeated Microsoft over and over again in the market, first in music players, then in smartphones, then in web browsers, then in tablet computing, and progressively in general software development tools and mobile app merchandising.

Apple surpassed Microsoft in market cap and then revenue in 2010 and then profits in 2011.

Apple is now worth an incredible $412 billion and sits on over $145 billion in cash reserves. Had Jobs simply focused on litigation, Apple may have been awarded a one-time windfall of $1.2 billion before collapsing into an increasingly worthless patent portfolio of a has-been hardware maker, just like Motorola Mobility and Nokia.

A patent stockpile begins

In the 1980s Apple had no patents to protect its Macintosh. In the mid 1990s, Apple joined the industry in beginning to patent virtually everything, a shift that occured largely in response to the previous decade's Macintosh, the largest and most expensive infringement of intellectual property that had ever occured in technology (evident across two decades of stock prices, below).

Source: Google Finance

Apple didn't use those patents to win a war against Microsoft, however. Instead, the company used them defensively to prevent an ongoing, crippling war of patent litigation that, without Jobs having negotiated a cross-licensing program with Microsoft in 1997, would almost certainly have derailed the development of both OS X and iPod as both products progressively beat Microsoft's own efforts in the marketplace.

Source: Google Finance

As a result, the last decade has seen a spectacular reversal of fortune between Apple and Microsoft (above). However, just as the decade of the 2010s began, a new battle among smartphone vendors erupted as Apple increasingly pushed its computing platform technology into the existing smartphone market dominated by telephony companies.

Existing mobile hardware vendors had vast patent portfolios related to wireless radio and data networks, while Apple entered the market with decades of Mac operating system and iPod industrial design patents.

Apple also had a new collection of mobile device patents filed with the launch of iPhone. The next segment looks at Apple's subsequent efforts to sell and license its technology in direct competition with Microsoft's copies.