Apple recently made a splash by announcing a new 12-inch MacBook that features a single port for both power and data transfers: USB-C, a new connector spec that may sweep away not just USB 2.0, but also Thunderbolt -- and possibly even Apple's Lightning.

The standard: USB 2.0 and its issues

It may be taken for granted now, but in the early 2000s, USB 2.0 was a major step forward. USB already existed, but v2.0 provided a common specification for transferring data at relatively high speeds, peaking at 480 Mbps, or about 60 MBps.

That's enough to support accessories like external hard drives or syncing a music collection to a smartphone or MP3 player. Powered USB 2.0 connections can also provide enough juice to run many external peripherals without a separate supply.

In recent years though, the format's limitations have become increasingly obvious. There are still many devices that USB 2.0 can't sufficiently power, and 480 Mbps has become frustratingly slow in an era when most storage is rated in gigabytes and terabytes, not megabytes. No serious video editor would work from a USB 2.0 drive unless they had to.

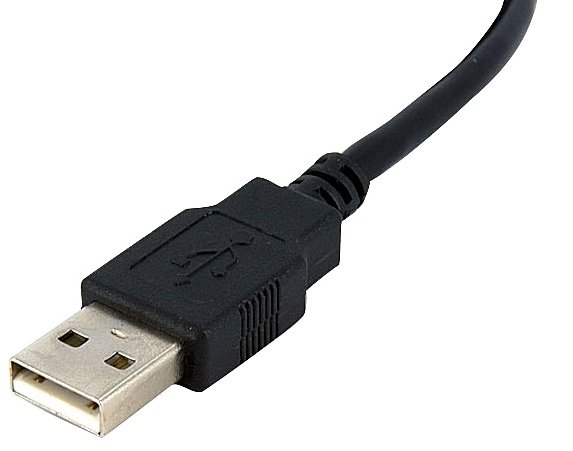

USB 2.0 also employs an infamous non-reversible Type-A connector. Many people complain that it's rare to properly plug in the connector on the first try.

Solutions: USB 3.0 and Thunderbolt

USB 3.0 has finally become a standard component on most Macs and Windows PCs, and provides one major upgrade: speed. The format tops out at 5 Gbps, which is more than 10 times as fast as its predecessor.

While USB 3.0 can be used across a variety of connector types, Apple's current Mac lineup and the overall PC market rely on the legacy, non-reversible USB Type-A connector for input.

For people demanding even more performance, there's Thunderbolt, a format co-developed by Apple and Intel. This merges PCIe, DisplayPort, and DC power channels together, with a maximum 10 Gbps for Thunderbolt 1-level devices and 20 Gbps for Thunderbolt 2. A third generation coming later this year will hit 40 Gbps, or a whopping 5 GBps.

And since Thunderbolt sports the same connector type as Mini DisplayPort, and it has enough power and bandwidth, Thunderbolt can additionally be used to connect one or more monitors and even daisy-chain up to six peripherals per port.

One might think this would be enough to help the format spread like wildfire, but in general, it hasn't caught on. It's used primarily by Apple computers, and relatively few Thunderbolt peripherals have been made. Most of those, naturally, are marketed toward Mac owners.

The next generation: USB-C

Enter USB Type-C, or USB-C for short, which promises to solve a variety of problems all at once.

Its definining trait is actually a smaller, rounded port accepting reversible connections. This should not only remove the clumsiness of USB but allow faster data transfers on ever-thinner devices, with Apple's new 12-inch MacBook being a leading example.

Though USB-C is backwards compatible, it's meant to be paired with USB 3.1, which is capable of 10 Gbps file transfers and can also supply power.

How fast? While USB-C can technically be paired with older, slower USB standards, it's really meant to be linked with USB 3.1, which scales from 5 to 10 Gbps. Accordingly, USB-C devices can blaze through tasks which were previously the domain of Thunderbolt.

This includes running 4K or quad-HD displays, due also in part to increased power throughput. Indeed USB-C can theoretically handle up to 100 W in either direction, which is why the new MacBook doesn't even need a MagSafe charging port.

Thunderbolt encapsulates DisplayPort, dedicating two 20 Mbps lanes towards displays. USB-C supports something called the "DisplayPort Alternate Mode," which allows native DisplayPort signals to be carried over one, two, or four lanes as needed, with the tradeoff that using all four lanes will reduce USB 3.1 functions to the 2.0 level, and that USB-C can't handle Dual-Mode Display Port, and hence passive (as opposed to active) DisplayPort adapters.

The takeaway is that a computer like the MacBook can use USB-C as its sole connection standard. Even full-scale desktops may eventually be lined exclusively with USB-C ports, jettisoning dedicated HDMI, DVI, and Ethernet ports as long as needed adapters are available.

Decisive factors

USB-C's core advantage may be its namesake universality. It is backwards compatible with legacy USB 3.0 and USB 2.0 out of the box, and will work with USB Type-A devices via an adapter. But more than that, it's guaranteed to have industry support.

Thunderbolt was an attempt to disrupt the industry, whereas USB is already omnipresent. In that sense the real obstacle to USB-C adoption is just the cost to device makers (and hence shoppers), but that's bound to shrink as more OEMs come on board.

Thunderbolt won't vanish completely, or at least overnight. Some professionals need 20 or 40 Gbps speeds, and USB still doesn't natively support RAID or TRIM, which are essential to more complex storage setups (connecting a RAID drive via USB requires a controller card, for instance). For the average person however, Thunderbolt may no longer be much of a selling point, something even Apple appears to have acknowledged with the MacBook.

What's interesting to consider is whether USB-C might replace Lightning, the Apple format used exclusively for iOS devices. Fundamentally Lightning is based on USB 2.0, and doesn't offer much of a difference beyond a compact, reversible head -- something USB-C could easily replace.

If Apple did make the switch, there would be number of concerns. Lighting's authentication chips are used to block unlicensed cables and accessories, and abandoning them would hurt Apple's accessory sales, or at least the company's control of the accessory ecosystem. It would also be important to manage power consumption to preserve battery life, and many iPhone and iPad owners would probably be upset by having some of their accessories rendered obsolete once again.

Apple might also just choose to upgrade Lightning with USB 3.0/3.1 compatibility. But in the Mac world USB-C seems destined to spread, and it might not be surprising to see more Macs in the near future without Thunderbolt.

Update: The MacBook actually uses an early iteration of USB 3.1, capped at 5 Gbps. The article has been updated to reflect that fact.