Just in its first few days, the launch of Apple Music has demonstrated that Apple can competently execute outside of its core hardware business. That has implications for its future ambitions in TV and automotive, as well as highlighting the vast gulf between it, Google and Microsoft.

Apple Music is not perfect in every way. Some users have complained that it does too much, such as in how it rearranges (or in some cases duplicates) their music library files. Others (including an editorial by Variety) have complained that it doesn't deconstruct everything quite sufficiently and therefore find it too simple. Other critics have worried that its interface is too complex (Variety actually claimed both in the same article).

These complaints have also been leveled upon Apple Watch, which various people--and sometimes even the same person--have called either too masculine or too feminine. Unsurprisingly, much of this criticism is coming from competitors or their mouthpieces, or simply people who like to voice all possible complaints they can theorize, even if those complaints are mutually exclusive, logical contradictions.

In addition to sharing criticisms with Apple Watch, there are also similarities in how the new Apple Music was critically received in comparison to some earlier Apple products, from the 1984 Macintosh to the 2001 iPod, the 2007 iPhone and the 2010 iPad. Critics imagined features that the first generation of those products "should" have incorporated, and didn't like various aspects of their initial implementation. That didn't stop each from going on to achieve incredible multi-billion dollar successes that monumentally changed the technology landscape.

While similarly imperfect in various ways, Apple Music is competent. It gets the right things right. And users are overwhelmingly liking the new service by a landslide in their public comments on Twitter.

A silver lining for Apple's once stormy iCloud

This is quite incredible, because while Apple "failed" repeatedly in the minds of critics while delivering one blockbuster hardware product after the next, cloud services have more honestly actually been a weak spot for the company. From iTools to .Mac to MobileMe to Ping to Maps, it's long been almost universally agreed upon that Apple has struggled to deliver robust, scalable, reliable cloud services when compared against leaders in the industry.

That has been changing however. When Steve Jobs outlined the future of iCloud in 2011, he strategically positioned the revamped internet services at the same level as iOS and OS X. The new vision for iCloud also "demoted" the Mac from the center of the "digital hub" to being just another device getting data from cloud services.

The user-facing iCloud services Apple began deploying worked fairly well, but its iCloud Storage CoreData APIs for developers were poorly received, and for some, basically unusable.

In 2014, Apple completely redesigned its approach and implementation for third party developers with CloudKit, a new internet service for storing and synchronizing app data in the cloud. To demonstrate that it works and is scalable and robust, Apple developed the new CloudKit-based Photos app and its iCloud Photo Library, along with iCloud Drive for iOS 8 and the Mac.

This year, Apple expanded upon its cloud progress with Photos for Mac, and at WWDC introduced CloudKit JS, which offers web client access to iCloud so developers can create cloud-synced apps for not just Macs and iOS devices, but also web clients and mobile apps on other platforms.

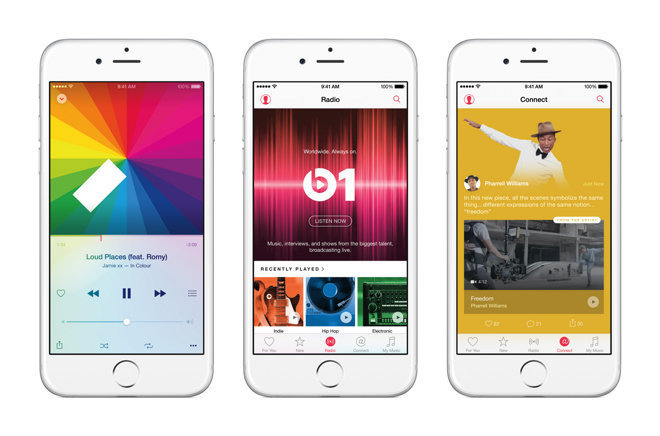

Rather quickly, Apple has transitioned to being a serious cloud services provider. That came just in time for the launch of Apple Music, an ambitious package including Beats 1 radio, on-demand streaming, Connect social networking features, and integration with the music users already have.

And while Apple still has to prove that it can retain and develop an audience of paying listeners, its new ability to deploy attractive, functional cloud services on-time, as scheduled--particularly given the exterior contention of having to deal with complex non-technical issues, including winning over the support of artists and their labels--also says something powerful about Apple's potential in video and film related to Apple TV, and its ability to enter new markets including automotive, using the same expert planning, operations, deal-making, engineering and marketing that have made Apple the richest and most successful public company in the world.

How Apple Music escaped the Ping of death

Apple Music could have been a disaster, or at least an embarrassingly sloppy effort by a company with lots of money to confidently expand into a market that it does not really understand. There have been lots of attempts to make comparisons to Ping, a previous social networking feature within iTunes 10 that Apple intended to enable artists to connect with fans back in 2010.

Ping failed (quite spectacularly) primarily because it began as a partnership with Facebook that Facebook pulled the rug on just prior to launch, hoping to get further concessions from Apple. Rather than rebuilding it from scratch, Apple launched it anyway with rudimentary commenting features that devolved into forums of unregulated spam and harassment.

iTunes 10 Ping

Ping in iTunes 10 looked like a tech product created in Silicon Valley, far from the music industry. Beats was built in Los Angeles, by people central to the music industry. Apple Music incorporates Beats' streaming product and music industry savvy with Apple's own in-house iTunes features and iCloud services.

Apple Music is nothing like Ping. Rather than initiating a shaky partnership with an outside firm with conflicting interests, Apple Music is fully owned by Apple. As an integration of Apple's existing iTunes services with the content subscription and artist curation features acquired as part of Beats, Apple Music is a legitimate collaboration of Tech and the Liberal Arts.

Apple Music incorporates Ping-like commenting features, and of course is not perfect in every way. There are feature requests and bug complaints on both the artist and user side. However, such vocal requests are evidence of success, not failure. People are actually using (and loving) Apple Music.

If Apple can continue to address these minor issues, it will not only have a product that keeps users happy with iTunes, but also one that attracts users from other platforms to Apple's, the same way that iTunes hooked millions of Windows users into exploring Apple's Macs after a positive experience with iPods and the iTunes Store.

It has become cliche among Apple's critics to refer to iTunes as a terrible product, but the reality is that Apple has attracted 800 million users to sign up for iTunes Store accounts with their credit cards. Despite a series of flaws, false starts (like Ping) and growing pains, iTunes has become the world's favorite way to spend money on media. And the second place is quite a ways behind it.

Apple makes the effort of building new things look really easy (think Apple Pay or Apple Watch), but to really appreciate the accomplishment involved in efforts like iTunes and Apple Music, take a brief look at its competitors.

Google Music

Back in 2011, Google launched its own Music Beta, with a cloud music locker but no music store because it built and soft-launched the product without the support of the music industry. Google Music is a lot like Google Wallet: years ahead of Apple, but so poorly planned and implemented that it completely squandered its vast head start.

Six months later, it finally sealed deals with three of the top four major music labels and officially launched Google Music, connected to Google+ for music sharing and Artist Hub promotional pages.

In 2012, Google executives were reported to be upset with the lack of interest in Google Music, and particularly dismayed its inability to bring in revenue. One aspect that hurt its adoption was the lack of a mobile app for iOS.

That means Google Music is a lot like Google Wallet: years ahead of Apple, but so poorly planned and implemented that it completely squandered its vast head start.

Google apparently expected its paid on-demand streaming music service to be quite popular among Android users, but instead got a taste of what its Android developers had already been eating: the platform does not attract people who want to pay for things, particularly not anything that can be pirated. Google Music mostly demonstrated the weakness of Android as a platform for supporting commercial apps and services.

Another significant difference in Google's approach was that it shunned modern H.264 AAC codecs to use MP3. Not only did it embrace the older technology, but it transcoded 256 kbps AAC music sources into 320 kbps MP3, a move that looks good on paper but sounds worse. Those antics occurred in conjunction with Google's efforts to derail H.264 video in support of Flash and then its own VP8/WebM.

Google's ideological warfare waged on intellectual property holders might have excited the base, but it resulted in an antagonistic relationship with both content creators and external IP developers, which in the end did not benefit the very demographic of "don't pay, pirate" fans that Android was catering to as an audience.

Google Music (along with WebM and Google+) turned out to be disappointing initiatives that failed to gain traction despite being pushed by the vendor in ostensible control of Android, Chrome OS and the world's most popular web search engine (by a wide margin). Simply having lots of capital and engineering talent wasn't enough for Google to deliver successful products and implement strategies that worked.

If Apple's success with Apple Music can offer some insight into its prospects for successfully launching TV and automotive products, as well as expansions of today's Apple Pay, Apple Watch, home automation, health and ResearchKit initiatives, the same can conversely be said about Google's track record of bungling Google TV, Glass, Google Wallet, Android Wear, Android@Home and its future prospects for Android Pay, self-driving cars and another crop of Glass and Android TV attempts.

Microsoft Windows Media Center

Microsoft's very different approach to music and video also failed, for reasons that are useful to contrast against Apple Music and iTunes. When iTunes first appeared, Windows Media Player had been leveraging Microsoft's near monopoly market position for a decade.

Initially a rough competitor to QuickTime for playback, by the late 90s WMP became part of Microsoft's strategy to deploy global, proprietary DRM that could earn the company licensing revenue not just from PCs but from emerging formats ranging from HD-DVD to streaming content and portable media devices.

Instead of "opening" things up like Google--using inferior formats to sell content from hostile media companies it didn't respect to its Android demographic of customers who don't pay for things--Microsoft developed state of the art media formats with difficult to crack DRM and cozied up to media companies with promises of locking up their content so customers couldn't even rip songs they bought to their own CDs as personal mixtapes.

Microsoft's customers might have paid for this, had it not been so draconian in its restrictions and flatly tone-deaf of the desires of real people. Microsoft also suffered from the fact that Apple was offering a much less restrictive alternative in iTunes.While Microsoft was building solutions for its partners that didn't solve problems for consumers, Apple was building a product for its customers--end users who were premium hardware buyers--that attracted the support of media partners and content creators

Microsoft responded to Apple's iTunes and iPod with an even flashier WMP tied to PlaysForSure DRM devices, then turned around and introduced its own Zune player with inferior, half baked software. It also diddled with terrible Windows Mobile products and pursued an ambitions media strategy around Windows Media Center, a playback hub for distributing audio and video and integrating with cable boxes and televisions.

An article by Extreme Tech recently lamented that Microsoft is now killing off WMC in Windows 10, writing that it originally "was an innovative and necessary product. Nothing did what it did at the time," while also observing that Microsoft's efforts to integrate with third party WMC Extender products "were pretty glitchy and difficult to use."

While the industry consistently demanded that Apple copy Microsoft's DVR and cable-centric approach in WMC, the company instead pursued a much simpler, easier to use living room ecosystem centered around Apple TV, AirPlay and app-like services that surf the trending wave of cord-cutting.

That includes the latest HBO Go service, along with Netflix and a growing array of other TV on-demand services. Apple Music is also integrated with AirPlay for easy playback at home (and CarPlay when driving). You can even see the currently playing Beats 1 track at a Glance on your Apple Watch.

So while Microsoft was building solutions for its partners that didn't solve problems for consumers, Apple was building a product for its customers--end users who were premium hardware buyers--that attracted the support of media partners and content creators.

Apple's enviable position of not needing to make money on Apple Music

Apple's primary profit engine is hardware sales. Commentators have frequently reminded their audiences (and each other) that even if Apple Music were widely successful, it wouldn't really move the needle for Apple's revenues. That is usually presented as a bad thing, but the reality is that selling media is hard, and much easier to pull off if you don't need to immediately make money on it.

Apple originally approached iTunes Music as a break-even effort to make sure that Macs and iPods could access top popular content in a world where Windows Media DRM appeared poised to dominate. Apple later added TV, movies, podcasting and iTunes U, not to generate money, but as additional reasons supporting the purchase of Macs, iPods and iOS devices. The iOS App Store has also been run from the start as a way to facilitate volume markets where small purchases support custom, exclusive content, not simply a way to make short term money.

Apple Music is a continuation of that effort to support a sustainable market for music, while also enticing interest in high quality hardware, where Apple makes virtually all of its money. Even if Apple only ever just broke even on Apple Music, it would still be earning far more money in attracting users to iOS and Macs (and Beats hardware). It's quite a luxury to be able to build a artist-centric business without immediately worrying about the short term Return On Investment. It's quite a luxury to be able to build a artist-centric business without immediately worrying about the short term Return On Investment

Microsoft's primary profit engine has long been software licensing. It was simply too hard to license software at a high enough value to warrant developing a ecosystem behind WMC, WMP, PFS and Zune. Microsoft built software for big media companies with the hope of squeezing end users, but that didn't work out, because few people wanted to buy into such a system. Microsoft's more recent efforts to build a hardware business like Apple's haven't worked out very well, from Zune to Surface. That makes it hard to invest in an ecosystem for an installed base that hasn't really materialized.

Microsoft has to consider the ROI as it contemplates building out new ecosystem initiatives, because there is no longer a licensing monopoly in place to pay for anything the company can dream up. That's why the company is shedding efforts like WMC, and why it gave up on Zune Pass, which had some similarities to today's Apple Music. Without a revenue engine supporting it, those efforts weren't sustainable.

Conversely, Google's primary profit engine is advertising. It built free software in hopes of creating new surface area for its ads, but that ad revenue can't support good software, let alone quality access to top popular content. Most problematically, Google is finding that it is hard to sell anything to its Android audience, which was drawn in by offers of free software, low cost hardware and cheap or free services supported by ads.

Google is getting lots of media attention for giving away loss leader hardware like its $35 Chromecast dongle and "free" (as in puppies) cloud services like Google Photos. It's interesting to note that nobody worries that these efforts "won't move the needle" for Google's revenues the way so many are wringing their hands about Apple Music failing to rival the iPhone in revenues. Also consider that despite all the applause for its cheap dongles and software services, these products offer no apparent way to even tangentially benefit Google's core ad business.

Everyone else in the streaming business actually needs to figure out how to make money selling access to content, because they all lack a hardware business to fall back on. It's also notable that the only other mobile hardware vendor that makes any money--Samsung--has also seen little success in building an ecosystem, whether for exclusive apps or popular content including music. Building an ecosystem is a lot of work but offers scant prospects for generating real revenue right away, if ever. It's a lot like opening up retail stores.

Ask Google, Microsoft and Samsung how their retail stores are going.