Law enforcement officials have continued to make their case against the new, heftier encryption introduced last year by Apple and Google for their respective mobile operating systems, charging once again that the changes are standing in the way of capturing murderers, pedophiles, sex traffickers, and terrorists.

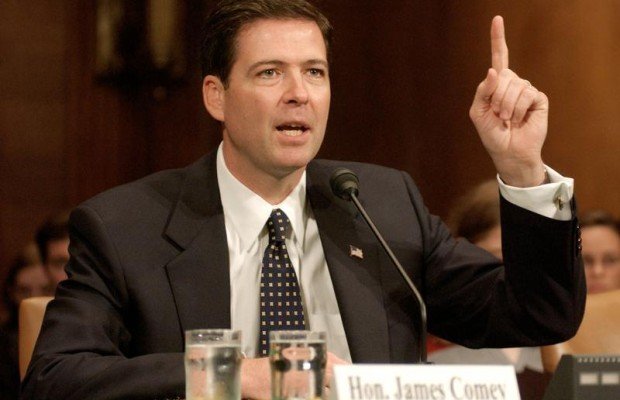

FBI director James Comey is among those who have argued for a government-accessible backdoor in consumer encryption systems.

"The new encryption policies of Apple and Google have made it harder to protect people from crime," a group of police and prosecutors wrote in an opinion piece published Wednesday by The New York Times. Manhattan district attorney Cyrus R. Vance Jr., Paris chief prosecutor François Molins, City of London Police commissioner Adrian Leppard, and chief prosecutor of the High Court of Spain Javier Zaragoza share the byline.

They argue that allowing people to encrypt their data without a backdoor amounts to forcing law enforcement "to proceed with one hand tied behind [their] backs," and that the actions which precipitated these changes --Â including the NSA data collection scandal --Â may be unfortunate, but do not justify the response.

"The new Apple encryption would not have prevented the N.S.A.'s mass collection of phone-call data or the interception of telecommunications, as revealed by Mr. Snowden," the piece reads. "There is no evidence that it would address institutional data breaches or the use of malware. And we are not talking about violating civil liberties -- we are talking about the ability to unlock phones pursuant to lawful, transparent judicial orders."

The relative lawfulness and transparency of those orders was not addressed.

Inaccessible, encrypted iPhones are said to have held up investigations including "the attempted murder of three individuals, the repeated sexual abuse of a child, a continuing sex trafficking ring and numerous assaults and robberies." Oddly, no such data for Android devices was offered, nor were any statistics that may have shed light on the benefits of encryption in stopping identity theft, blackmailing, or similar crimes when handsets are stolen.

This is not the first attack by law enforcement on widespread mobile phone encryption, and it is unlikely to be the last. Arguing that such encryption provides only "marginal benefits," Vance, Molins, Leppard, and Zaragoza call on government to regulate it --Â a policy which has been tried, and failed, before.