As expected, Apple intends to argue its First Amendment rights as part of a multi-pronged legal strategy designed to flout a court order compelling the company unlock an iPhone linked to last year's San Bernardino shootings.

Theodore Boutrous, Jr., one of two high-profile attorneys Apple hired to handle its case, said a federal judge overstepped her bounds in granting an FBI motion that would force the company to create a software workaround capable of breaking iOS encryption, reports the Los Angeles Times.

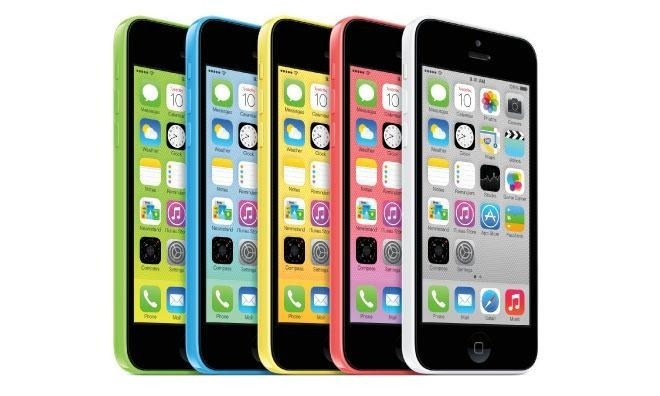

Specifically, U.S. Magistrate Judge Sheri Pym last week ordered Apple to help FBI efforts in unlocking an iPhone 5c used by San Bernardino shooting suspect Syed Rizwan Farook, a directive that entails architecting a bypass to an iOS passcode counter. Government lawyers cited the All Writs Act of 1789 as a legal foundation for its request, a statute leveraged by the FBI in at least nine other cases involving iOS devices.

While the act itself is 227 years old, lawmakers have updated the document to cover a variety of modern concerns, most recently as applied to anti-terrorism operations. In essence, All Writs is a purposely open-ended edict designed to imbue federal courts with the power to issue orders when other judicial tools are unavailable.

A 1977 Supreme Court reading of the All Writs Act is often cited by law enforcement agencies to compel cooperation, as the decision authorized an order that forced a phone company's assistance in a surveillance operation. In Apple's case, however, there is no existing technology or forensics tool that can fulfill the FBI's ask, meaning Apple would have to write such code from scratch.

"The government here is trying to use this statute from 1789 in a way that it has never been used before. They are seeking a court order to compel Apple to write new software, to compel speech," Boutrous told The Times. "It is not appropriate for the government to obtain through the courts what they couldn't get through the legislative process."

Boutrous intimated that the federal court system has already ruled in favor of treating computer code as speech. In 1999, a three-judge panel of the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, which covers California, ruled that source code relating to an encryption system was indeed protected under the umbrella of free speech. That opinion was later rendered moot, however, meaning there is no direct legal precedent to support Apple's arguments.

The comments expressed by Boutrous echo those of Apple CEO Tim Cook, who earlier this week called for the government to drop its demands and instead form a commission or panel of experts "to discuss the implications for law enforcement, national security, privacy and personal freedoms."

Apple is scheduled to file its response to last week's order on Friday.