Security researcher Joe Fitzpatrick, one of the few sources named in Bloomberg Businessweek's bombshell China hack investigation, in a podcast this week said he felt uneasy after reading the article in part because its claims almost perfectly echoed theories on hardware implants he shared with journalist Jordan Robertson.

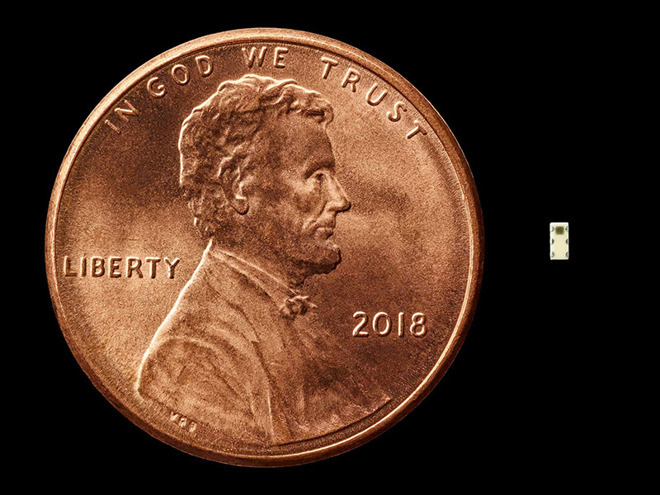

Graphic illustrating size of supposed Chinese spy chip allegedly embedded in Apple servers.

Source: Bloomberg Businessweek

Fitzpatrick detailed his dealings with Bloomberg to Patrick Gray of Risky Business in a podcast published on Monday.

The security specialist first spoke with Robertson last year, just prior to giving a presentation on hardware implants at the DEF CON hacking convention. The impetus behind Robertson's questioning was not made clear to Fitzpatrick until last month.

In his conversations with the journalist, Fitzpatrick detailed how hardware implants work, specifically noting successful proof-of-concept devices he demonstrated at Black Hat in 2016. While he is a security researcher, Fitzpatrick is not in the business of selling such devices to customers -- let alone nation states -- and is for the most part working off theories derived from years of teaching others how to secure their own hardware.

When asked what, exactly, he found strange about Bloomberg's claims, Fitzpatrick said, "It was surprising to me that in a scenario where I would describe these things and then he would go and confirm these and 100% of what I described was confirmed by sources."

Further, the story as told "doesn't really make sense." As Fitzpatrick notes, there are easier, more cost-effective methods of attaining backdoor access into a target computer network.

Bloomberg in its article claimed Chinese operatives managed to sneak a microchip smaller than a grain of rice onto motherboards produced by hardware supplier Supermicro. Supposedly designed by the Chinese military, the chip acted as a "stealth doorway onto any network" and offered "long-term stealth access" to attached computer systems.

Nearly 30 companies were reportedly impacted by the breach, though only Amazon and Apple were mentioned by named in the story. Both companies have released strongly worded denials, with Apple characterizing the report as "wrong and misinformed."

"Spreading hardware fear, uncertainty and doubt is entirely in my financial gain, but it doesn't make sense because there are so many easier ways to do this," Fitzpatrick said, referring to the purported hardware implant. "There are so many easier hardware ways, there are software, there are firmware approaches. There approach you are describing is not scalable. It's not logical. It's not how I would do it. Or how anyone I know would do it."

Fitzpatrick said as much to Robertson in an email exchange, pointing out the described backdoor attack can be just as easily accomplished by remotely modifying the firmware of "most BMCs" (baseboard management controllers) as many run outdated software. He went on to ask whether the additional hardware sources supposedly discovered on the boards were merely counterfeit prevention, bypassing implants or some other functional component added by a legitimate third-party.

In one email exchange, he cautioned that inexperienced observers might mistake combination hardware -- flash storage and a micro controller, for example -- as a hardware implant. The Bloomberg investigation claims the spy chips were incorporated into another, inconspicuous component that took on the appearance of signal conditioning couplers.

Robertson in an emailed reply confirmed that the idea "sounded crazy," but said "lots of sources" corroborated the information. Fitzpatrick was not convinced.

"And you know I'm still skeptical. I followed up being like, 'Yeah, okay if they wanted to backdoor every single Supermicro motherboard, I guess this is the approach that makes sense," he told Gray. "But I still in my mind I couldn't rationalize that this is the approach any one would choose to take."

Robertson was unable to produce photographic evidence of the chips in question, saying they were described to him by protected sources. Indeed, Robertson in September asked Fitzpatrick what a "signal amplifier or coupler" looks like, suggesting the publication narrowed the attack package down to that particular component. Fitzpatrick sent Robertson a link to a very small signal coupler sold by Mouser Electronics.

"Turns out that's the exact coupler in all the images in the story," Fitzpatrick said.

While the illustration used in the Bloomberg story is just that, Fitzpatrick argues similar components would be an unlikely choice for the attack vector described. Larger, albeit less conspicuous hardware is available, namely chips that mimic the SOIC-8 package. Further, pint-size signal couplers are not standard fare for server motherboards that do not include Wi-Fi or LTE.

"But it's just not the easiest package to choose to use with something like this, it's not a package you'd expect to find in a motherboard," he said. "It's something where if it's on your motherboard you'd be like, 'What the heck is that doing there for?'"

Whether the Supermicro boards in question integrated wireless radio technologies is unclear.

Bloomberg stands by its original reporting. The year-long investigation incorporates information from 17 sources, some of whom work or worked for the allegedly impacted companies or the U.S. government.

"As is typical journalistic practice, we reached out to many people who are subject matter experts to help us understand and describe technical aspects of the attack. The specific ways the implant worked were described, confirmed, and elaborated on by our primary sources who have direct knowledge of the compromised Supermicro hardware. Joe FitzPatrick was not one of these 17 individual primary sources that included company insiders and government officials, and his direct quote in the story describes a hypothetical example of how a hardware attack might play out, as the story makes clear," a Bloomberg News spokesperson said in a statement to AppleInsider. "Our reporters and editors thoroughly vet every story before publication, and this was no exception."

Apple executives and high-ranking security engineers said an internal investigation into Bloomberg's claims revealed no evidence of the hardware tampering in question, nor did the company identify unrelated incidents from which the allegations could have conceivably arisen.

Apple said much the same in a letter to Congress issued over the weekend.

For his part, Fitzpatrick said Bloomberg's account of what transpired, if anything, is suspect.

"I have the expertise to look at he technical details and I have the knowledge to look at the technical details and see that they're jumbled. They're not outright wrong, but they are theoretical," he said. "I don't have the knowledge to know the other conversations -- the other 17 sources and what they said, but I can infer based on the technical side of things that the non-technical side of things may be jumbled the same way."

Updated with response from Bloomberg spokesperson.