At launch, the Macintosh was far from a hit, far from being affordable and even far from being completely workable. Yet, that original model did succeed in forever changing computing not just for its fans, but for the entire world.

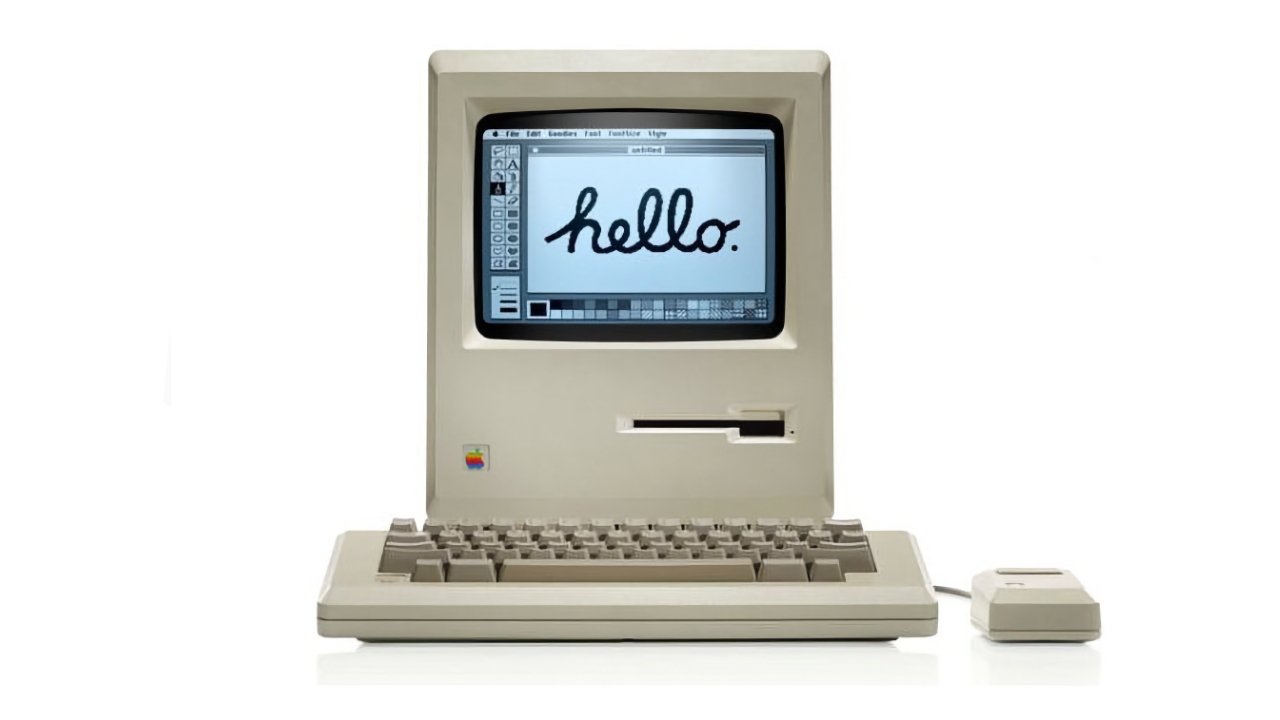

The original Macintosh from 1984

"You've just seen some pictures of Macintosh," said Steve Jobs at the official launch of the Mac. He was on stage at the Flint Center in De Anza College, Cupertino, on Tuesday, January 24, 1984. "Now I'd like to show you Macintosh in person."

The Mac he unveiled looks little like today's machines. It had a small, monochrome monitor, blocky graphics and the kind of synthesized voice that you wouldn't even get in a toy now. Yet crucially, it also looked nothing like the computers of its time.

"Up until that moment," wrote Steven Levy in his book about the Mac, "when one said a computer screen 'lit up,' some literary licence was required. By the end of the demonstration, I began to understand that these were things a computer should do. There was a better way."

Levy was one of the journalists who got an early demo when Apple previewed the Mac in October and November 1983. This was part of the company's dual-pronged aim of having everyone talking about the Mac at its launch but also everyone being able to get right away.

As well as briefing journalists, Apple was manufacturing the Mac and getting it into resellers. And there were videos. It's possible that an outside news agency or station decided to cover the Mac but what's more likely is that Apple itself made a series of videos as it does today.

Editions of an eight-part Evolution of a Computer series come and go on YouTube, though at time of writing are not available. They look most like an early Electronic Press Kit, and one showed then-CEO John Sculley inadvertently revealing his entire attitude to computing.

"With Macintosh we have put together an extremely well-coordinated, very powerful consumer marketing program to introduce this product," he says.

Bless. Compare him to someone else in these videos, someone you'll recognize immediately. "We're gambling on our vision. And we would rather do that than make 'me too' products. Let some other companies do that," said Steve Jobs.

Perhaps Jobs would come to rue saying that when later Microsoft did exactly this with Windows and much later when Google did so with Android.

Yet if they were copiers, Jobs was not the original either. He did not invent the Macintosh, as much as he would regularly let people believe.

Jef Raskin

In fairness, the Mac we got that day in 1984 would not have been what it was without Jobs. It wouldn't have had a mouse, for a start. "I couldn't stand the mouse," Apple's Jef Raskin told Owen W. Linzmayer in Apple Confidential 2.0. "Jobs gets 100 percent credit for insisting that a mouse be on the Mac."

Raskin, however, gets 100 percent credit for starting the project, starting the basic ideas of what the machine would do, and for calling it Macintosh. He even gets credit for how the mouse turned out, as despite his preference for a joystick, it was his work that resulted in the one-button model when others use two or three.

Talking to High Tech Heroes around 1987, Raskin explained that he had been a regular at the Xerox PARC facility -- "I had an honorary beanbag chair [there]" -- long before Steve Jobs's fateful visit in late 1979.

"They had this three-button mouse and I couldn't keep track of which button was which. And so when I came to create the Macintosh project... I realized you could do all that you have to do with a one-button mouse. It took me a while to convince people that was possible."

Jef Raskin, who died in 2005, wasn't always precise in his telling of how the Macintosh came to be but in either Spring or September of 1979, he was talking with Apple chairman Mike Markkula. Either Raskin straight-out pitched the idea for Macintosh or he first turned down Markkula's request that he work on a game machine.

Whichever it was, he says in that High Tech Heroes interview that he had been thinking about the future of Apple.

"The projects that were in the works were the Apple III and the Lisa. I [told Markkula that] I thought the Apple III didn't have the technical pizazz to take us to the future... and the Lisa was going to be overpriced and too slow. So I proposed a thing which I called Macintosh."

Apple V

Even though the company was then working on the Apple III, Raskin considered the name Macintosh to be just a code one and that the final machine would be called the Apple V. It was to be a simpler machine than previous Apple computers, or at least it was in terms of how easy it was to use.

"There were to be no peripheral slots so that customers never had to see the inside of the machine," he said. He proposed an all-in-one machine that had bitmapped graphics -- so that the screen could show any image, not just DOS-like characters -- and in 1979 he planned to make it sell for $500. That's the equivalent in 2024 of $2,172.82, which is slightly more than the cost of a base model Mac Studio.

Raskin also imagined the machine would be out by Christmas 1981. Instead, it launched in January 1984 and went on sale for $2,495 or fractionally under $9,000 in today's money.

What happened in between

Between Raskin's idea and the Mac shipping, Steve Jobs happened. And John Sculley happened too. Having originally disregarded the Mac project as unimportant, Steve Jobs changed his mind when he was removed from the Apple Lisa project.

One of the reasons he was removed was that he had now visited Xerox PARC and had been pushing to change the Lisa to be more like the machines he'd seen there. He still had that in mind and Macintosh was this little project nobody on Apple's board seemed to care about, so they found each other.

It was late 1980 or early 1981 when Jobs really took over the Mac project -- and then steadily cut Raskin out until the Mac's creator resigned in March 1982.

Without question, it is unfair that Raskin fails to get credit for the Macintosh and it is undoubtedly true that Jobs didn't deserve it. However, Raskin did get another chance to put his ideas into practice and he created the Canon CAT.

Ad for the Canon Cat (Source: Archive.org)

The CAT was a failure where the Mac was this giant success.

Eventually.

What happened afterwards

The launch of the Macintosh was a giant success in terms of marketing and publicity, so perhaps Sculley was right. It was not, initially, much of a hit in terms of being a visionary product because all it had was vision. You couldn't do a lot with the original Macintosh, so maybe Jobs was wrong.

Both men, though, pushed the price up. Jobs by demanding higher specifications and then Sculley by spending $78m ($277 million today) on marketing -- and subsequently trying to recoup all of that as fast as possible.

So the original Mac that launched on January 24, 1984, was a lumbering and very costly machine. Even so, it transformed the computing industry and ultimately it actually, genuinely did change the world.

You can trace the history of the screen you're reading this on all the way back to the very first Macintosh. And on that screen of yours, you can watch something else from the introduction of the Mac.

The Apple of 1984 and the Apple that created the Macintosh also created one of the most famous adverts of them all. It had aired on TV during the Super Bowl two days before and Jobs screened it again as part of the launch.

Since those days, and surely because of what the Mac started, television is no longer the screen that everybody watches the most. Today we're more likely to be online, too, and it was of course here that Tim Cook chose to celebrate the Mac's 35th anniversary in 2019.

Tim Cook tweets about the Mac's 35th anniversary in 2019

Since then, the Mac has been undergoing the enormous change to running on Apple Silicon. It's truly an enormous change, but it's been done so well that it's easy to forget what an effort it must be taking Apple.

And for all the change, all the developments, all of the advances in the years since 1984, the Mac is still the Mac.

It was a flop when it launched, but the Macintosh got so much right that it genuinely changed the world. Eventually.