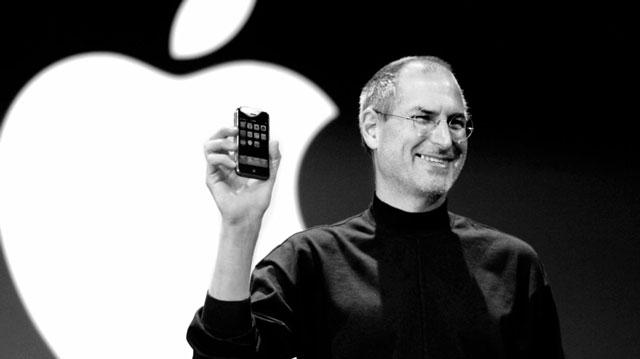

In May 2007, I interviewed Steve Jobs on the subject of native apps for the iPhone months before the new phone first went on sale. Six years later, his answers are now haunting Google's rival Android platform because the search giant has failed to heed the advice leaking from the top of Apple's ship.

Apps on the original iPhone OS

Apple had just demonstrated the brand new iPhone earlier that January, showing off a series of new "desktop class" mobile apps designed for it including a mobile multitouch Safari, Mail, Maps and iPod. But Jobs had also stated that third party developers would be able to build their own apps, albeit using web standards (HTML and JavaScript).

Incidentally, these custom web apps (two examples, below) are the same sort of "software" that Palm's webOS ran, and that Google's ChromeOS runs, and what many Windows Metro WP8/Windows 8 tablet apps are, all of which were introduced years after the iPhone and its initial web apps model for third party software were announced in 2007.

Apple's web apps plan essentially relegated third party apps to exist on the level of Dashboard widgets, something that Apple's developer community vociferously rejected. They insisted Apple should give them access to develop native iPhone apps, enabling them to create software as speedy, sophisticated and powerful as the apps Apple had developed for the iPhone's Home screen.

For the next year, Apple didn't offer a mechanism to support the sale or distribution third party native apps on the iPhone (or iPod touch). In early 2008 however, Apple unveiled its new App Store along with iPhone OS 2.0 (later renamed iOS 2.0), opening the floodgates for what would become the largest and fastest growing software platform and market in history.

The story of Apple opposing native apps

Certain parties have since rewritten the history of the App Store to tell a very different story: one where Steve Jobs was opposed to the very idea of native apps. This version of events maintains that Apple didn't have any plans for an App Store until the jailbreak community (and perhaps some early Android hobbyists) demonstrated how great apps could be, forcing Apple to reluctantly open its own app store in response.

As a headline in the Los Angeles Times last week stated, "If Steve Jobs had his way, we wouldn't be celebrating the Apple App Store's 5th anniversary!"

The story insists that Jobs' Apple was wildly opposed to native apps and "tried its best to put a stop to" native apps being developed by jailbreak users, up until October 2007 when "Apple announced it would relent and create a way for people to write apps for the phone," something it finally outlined the following March and delivered that summer.

The truth in between

It is true that Apple initially outlined plans for web-based apps, and that it opposed jailbreaking (that is, defeating the security model of the phone to "break open" full access to its core software). It's also true that the App Store was far more wildly successful than anyone at Apple had anticipated.

However, Jobs didn't set out to simply stop native iPhone development out of ignorance of its potential. I know that because I asked Jobs about it at the company's 2007 shareholder meeting, amplified at the microphone in front of the assembled news media tasked with covering the event.

When I asked "does Apple recognize the needs of large, institutional buyers who are excited about the prospect of applying low cost, handheld computers with their own custom development?" Jobs clearly replied that Apple was aware of the demands of third party developers, but that the company was also still working on how to balance the needs for secure software and deployment. It was a work in progress.

I didn't see Jobs' answer reported by anyone in the news media. Instead, Ellen Lee of the San Francisco Chronicle published a story that invented a parallel universe where Jobs was "feisty" and constantly "firing back" at questions, while Troy Wolverton of the San Jose Mercury News similarly tried to focus dramatic attention on supposed "shareholder discontent" related to stock option backdating that had ended years prior.

Some members of the media did manage to repeat Jobs' quip about engineering work in general: "I wish developing great products was as easy as writing a check. If that were the case, then Microsoft would have great products." That was awfully close to being the same message.

Full contempt and derision for every Apple decision

The journalists in attendance weren't the only ones to fail to grasp what Jobs was really saying. Vocal critics of 2007 also took issue with Apple's lack of support for applets based on Sun's Java, Qualcomm's BREW, and Adobe's Flash platforms on the original iPhone (Flash being an issue that raged another five years).

ABI Research analyst Phillip Solis felt moved to publish a note saying, "we must conclude at this point that, based on our current definition, the iPhone is not a smartphone, but rather a high-end feature phone," all because Apple hadn't opened a third party software market like Palm and Microsoft.

Add up the historical recommendations and demands of third party developers, pundits and industry analysts, and you get a community-designed platform that looks a lot like Android: one that downloads executable software from any source, supports various middleware platforms like Flash, lets users manually manage how the system launches and terminates background apps, and does away with all DRM restraints to make sure end users can promiscuously share files and apps as freely as they desire.

The problem is: that committee design has failed to make Android a good platform for either users or for developers. By not making any hard choices and giving people what they said they wanted, Google simply abandoned the future to cling tenaciously to the past.

Rather than conceptualizing and engineering really new solutions to historical computing problems as Apple did with iOS, Google has only attempted to wrest control away from iOS via volume shipments and has effectively sent mobile computing back in time into the 1990s, resulting in the same malware, spyware, viruses and usability issues of Windows.

However, things on Android are worse than Windows ever was because unlike the conventional 1990s PC, today's modern mobile devices have GPS tracking features, socially connected accounts that link together individuals' private information, always-on mobile network connections linked to a billable mobile phone/SMS account or credit card, camera and audio recording features paired with private photo albums and logs of sensitive communication records, the potential to serve as both a user's primary media player and computing device, all while being a small device powered by preciously finite battery capacity.

It's as if Google entered the auto business but declined to incorporate seat belts and airbags because it never noticed a need for such features when it was riding trains around in the previous century.

How Apple addressed the terrible mobile apps market

In quite stark contrast to Google, Apple surveyed the rather miserable mobile landscape that existed prior to the iPhone before setting out to build its own alternative mobile platform, taking note of what the problems were and how they could be effectively solved.

As I documented in early 2007, it was a world where a simple game like Texas Holdem cost $20 on Palm OS or cost $3 per month on a BREW subscription billed to your feature phone by Verizon Wireless. The Palm OS version of Bejeweled cost $20 and a "Pocket Tunes" MP3 player demanded $37.

2007 Texas Holdem $20 for Palm, $5 for iPod, or $3/month on Verizon BREW

It was world where Windows Mobile users were expected to shell out $75 for WorldMate Pro, a world clock app with access to weather forecasts and flight information. WiMo users also needed to pay $20 for a real email application, $30 to manage your contacts, $15 to view photos, $20 to play MP3s, $30 for a calculator, $25 to read PDFs, $30 to take notes, and $25 to find and launch apps with Propel, an app billed as "the ultimate launcher - you'll be amazed at how snappy and straightforward launching applications, finding contacts and keeping in touch will be!"

These were actually some of the top popular apps in Microsoft's Windows Mobile Marketplace. Apple incorporated all of these "third party apps" for free on the iPhone, along with a mobile browser that actually worked and with a custom designed app providing a slick interface for Google Maps that was far better than anything Google had delivered for a mobile phone.

These prices seem really high in retrospect, but they were set high for good reason: most mobile apps were being wildly pirated, so developers had to charge enough so that the minority who did pay were subsidizing this sieve of a market. Apple took note.

While the populist retelling of history suggests that Apple suddenly figured this all out in 2008 at the iPhone's first anniversary (after being schooled by jailbreaking hackers of the utility of software), the reality was that it took some time to develop a secure SDK and app deployment model to accommodate third party development.

This didn't all happen between Apple's announcement in October 2007 and its public release the next summer. We know this because Apple was shipping the beginnings of the App Store business model in the fall of 2006, a year before the iPhone.

Sell hardware, open apps market

In the fall of 2006, Apple launched a series of $4.99 iPod games as a new feature for the 5G iPod. The new iTunes games store opened a year after Apple had first released the 5G iPod. That ensured that there were millions of customers in place ready to buy games once the new titles hit the iTunes Store.

This is, of course, the exact same thing Apple did with the iPhone in 2008. It perfectly solved the historical catch-22 facing new platforms: why would developers make software for a platform that doesn't yet exist and has no users, and why would end users buy into a new platform for which there is little or no new software?

The iPod games of 2006 were clearly not a huge business initiative for Apple. It was a learning experience. The company was experimenting with how to deploy DRM-secured software in a way that benefitted users (the games were good quality, worked well and cost very little) and developers (there would be little piracy, so they could still make money despite charging very little per game).

Jobs explained the key to marketing mobile software

Given that Apple had very publicly launched iPod games in 2006, it was somewhat curious that the world remained completely baffled at why Apple didn't just throw open the iPhone to third party development from day one. Even more baffling is the expectation that Apple would welcome Java or Flash software on its platform, given that all of the mobile software available for either was extremely low quality junkware."We’re trying to do two diametrically opposed things at once—provide an advanced and open platform to developers while at the same time protect iPhone users from viruses, malware, privacy attacks."

However, Jobs continued to explain in public what Apple was doing. A few months after I posed my own custom app development question in May, Jobs further explained the iPhone app situation on stage at the Wall Street Journal "All Things Digital" conference, describing the App Store engineering task as a "wrestling" between security on one hand and an open platform for apps on the other.

Several months later in October, Jobs came out with one of his rare public blog entries where he stated, "Let me just say it: We want native third party applications on the iPhone, and we plan to have an SDK in developers’ hands in February. We are excited about creating a vibrant third party developer community around the iPhone and enabling hundreds of new applications for our users. With our revolutionary multi-touch interface, powerful hardware and advanced software architecture, we believe we have created the best mobile platform ever for developers."

Jobs' next comments, in retrospect, sound eerily prophetic: "It will take until February to release an SDK because we’re trying to do two diametrically opposed things at once—provide an advanced and open platform to developers while at the same time protect iPhone users from viruses, malware, privacy attacks, etc. This is no easy task. Some claim that viruses and malware are not a problem on mobile phones—this is simply not true. There have been serious viruses on other mobile phones already, including some that silently spread from phone to phone over the cell network. As our phones become more powerful, these malicious programs will become more dangerous. And since the iPhone is the most advanced phone ever, it will be a highly visible target."

Google has ignored Jobs' warnings at its own peril, but Jobs didn't arrogantly speak of secure mobile software development as an idea Apple had come up with independently. He credited Nokia.

"Some companies are already taking action," Jobs wrote. "Nokia, for example, is not allowing any applications to be loaded onto some of their newest phones unless they have a digital signature that can be traced back to a known developer. While this makes such a phone less than 'totally open,' we believe it is a step in the right direction. We are working on an advanced system which will offer developers broad access to natively program the iPhone’s amazing software platform while at the same time protecting users from malicious programs.

"We think a few months of patience now will be rewarded by many years of great third party applications running on safe and reliable iPhones," he concluded, before adding, "P.S.: The SDK will also allow developers to create applications for iPod touch."

Anyone who thinks Apple waited around until October 2007 to start work on the iPhone 2.0 SDK because the company needed to be prodded into action by the jailbreak community simply does not understand how engineering projects work.

Why Android doesn't have great apps

Apple wasn't just looking at the mobile mistakes of Palm and Microsoft, but was also taking note of some of the smart moves occurring at other companies. That included Nokia's app signing (preceded by video games vendors) and Microsoft's Exchange push messaging architecture (which took cues from Blackberry).

While Google was asking the community to replicate a license-free version of Sun's Java on Linux to serve as its ad-optimized mobile platform, Apple was actually engineering a new platform that learned from both the best practices of the industry's leaders as well as their mistakes. It's not surprising why Apple's App Store succeeded and Google Play hasn't; Apple did the work Google failed to do.

At the 2008 release of the App Store, Apple not only launched its iPhone SDK with app signing, but it also launched push messaging based on Exchange ActiveSync, and outlined plans to leverage push notifications to save battery life on mobile devices.

Apple has since brought both concepts to the Mac desktop too, introducing signed apps in the Mac App Store and incorporating push notifications for apps and, in OS X Mavericks, even web sites.

Google sort of followed suit on app signing, but enabled developers to self-sign their own apps. This "opened" Android's software model, but at the expense of Google exercising any real control over the real identity of apps. While it's possible to crack and steal iOS apps, it is more difficult than on Android.

It's also significantly more difficult to crack, hack and resell stolen iOS apps as your own work. Because Apple runs the only App Store for iOS, it can (and does) stop such activity. One recent issue was resolved by Apple the day after it was reported.

Google has no power to stop rogue developers from stealing legitimate Android apps, putting their own name on it and reselling it as their own work. This is routinely done for easy money, but it is also done to distribute malware and spyware.

This has resulted in Android harboring more than 90 percent of all mobile malware, but more importantly, it has had a very chilling effect on third party developer investment in the Android platform. Why bother to create innovative apps for Android if they can be stolen and resold on any number of third party stores? And why align with a platform that pays no heed to copyright abuses?

It's not the store, it's how you run it

While Google has invested some efforts in trying to catch up with Apple's App Store, it's clear Google's main priority has been to deploy a huge volume of Android devices with the assumption that this will automatically stoke demand for Android software.

There's a number of problems that are keeping this strategy from working. One is simply an issue of quality, evidenced in the security flaw discovered by Bluebox Security that defeats Android's app signing model across the entire installed base.

This issue is aggravated by Android's fragmentation, as it would require expensive efforts to create and test updates to patch the hundreds of millions of different Android phones out there with this flaw.

Given that Android licensees can't be bothered to roll out other security patches or even Google's latest Android version across the vast majority of their active installed base of users (Duo Security noted that more than half of Android devices are vulnerable to at least one of the known Android security flaws), there's no basis for believing that they'll bother to roll out this particular app signing patch.

Google hasn't even rolled out patches for its own Nexus devices yet.

But even if this issue magically vanished, the problem remains that Google hasn't copied Apple's security and curation work that has made the App Store successful. Retroactively addressing security on your platform isn't easy. Just ask Microsoft.

Many cooks in the Android kitchen

Android also faces many of the same "too many cooks" problems Microsoft deals with on Windows (and Windows Phone).

When Google and Samsung partnered on the Galaxy Nexus, the incorrect signing key was used to sign apps on devices in the German market, so that when users logged into Google Play, they got weird errors trying to update their phones and Google's apps wouldn't update property.

A problem with Android? With Google because it's a "Nexus?" Or because it's Google Play? Or because it's Google's apps? Or with Samsung, the manufacturer? Finding out which it is is an exercise for the buyer. In iOS land, everything is simply Apple's fault, and Apple takes care of it.

What it really boils down to is that Apple "wrestles" with such issues before deploying its products. The layers of key signing problems Google has struggled on Android have been after the fact, the result of not giving enough thought to privacy, security and accountability while developing its products.