The wholesale appropriation of Apple's Macintosh technology portfolio by Microsoft in the early 1990s had a profound effect upon how the industry began to think about intellectual property and protecting innovation through patent filings.

In particular, it influenced Apple's strategy for selling Macs and mobile devices as well as licensing the technology behind both, a new shift that would eventually play a key enabling role in Apple delivering the iPod and iPhone, sparking the iPhone Patent Wars.

The first segment focused on the patent attacks targeting iPod & iTunes, cases where Apple settled out of court as quickly as possible, although not before neutralizing as many incoming patents as it could. A second segment looked at the computing world before patents were in widespread use, particularly involving Xerox, Macintosh and Microsoft's Windows. This segment looks at Apple's subsequent efforts to sell and license its technology in direct competition with Microsoft's copies.

Bleak prospects for Apple's hardware business

By 1990, it was becoming apparent that Apple's entire business model for selling sophisticated new hardware technology--developed with upfront investments of tens of millions of dollars and involving years of effort--was at risk. Any new product Apple could develop was quickly matched by Microsoft's promise to release its own version in the near future.

Microsoft Windows simply scraped the uniquely valuable cream off the top of Apple's work and licensed it to "PC clone" hardware makers, leaving Apple forced to compete against a copy of its own work. Additionally, any new product Apple could develop was quickly matched by Microsoft's promise to release its own version in the near future, typically within two years.

This increasingly left Apple in an impossible predicament where every dollar of investment into innovation was instead working to profit and strengthen its competition.

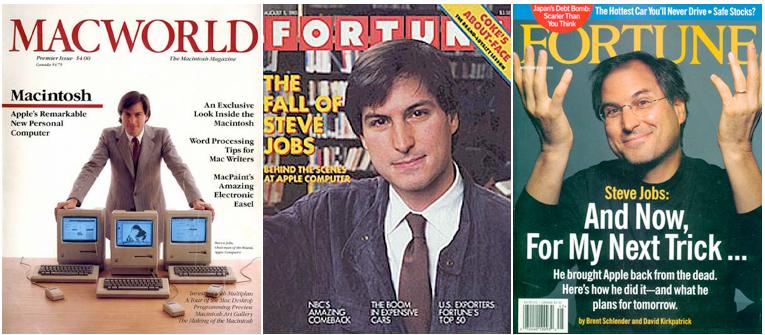

Between the departure of Steve Jobs in 1985 and his return that began at the end of 1996, Apple's focus grew increasingly distracted and splintered into internal factions that prevented it from effectively competing in the market. Apple's efforts to collaborate in a series of partnerships and licensing programs largely just complicated its problems.

However, the company also demonstrated a prescient understanding of where technology was headed, resulting in investments that appeared to be failures until the legal protections of patents and copyright rewarded it with a second chance to return to a leadership position.

Apple's distractions led to duplication

Apple didn't immediately recognize the full severity of the threat posed by Microsoft because throughout the late 1980s Windows was not taken very seriously in the industry.

Until it lost in court in 1992, Apple also appeared confident that it could stop Microsoft's infringement the same way its other "look and feel" lawsuits had stopped HP and DRI from closely copying features unique to the Macintosh.

A more credible threat seemed to be IBM's PS/2 hardware running the emerging OS/2, a joint software development project between IBM and Microsoft that replaced DOS with an advanced new operating system foundation. Until 1990, Microsoft presented Windows as an interim product to make DOS easier to use until OS/2 arrived.

Apple was also more concerned with NeXT (above), the advanced Unix-based workstation developed by Steve Jobs between 1986-1989 with the assistance of a number of former Apple employees. NeXT was essentially what Jobs had wanted Apple to develop internally in the BigMac and Macintosh Office programs.

Prior to Jobs' departure, Apple's executives didn't believe the projects were sound investments. After Jobs left, they regarded it as dangerous competition. In 1988, Apple launched A/UX (below), an implementation of the Mac desktop hosted on top of Unix, providing an limited subset of NeXT was offering.

Source: Toasty Tech

Three years later, Apple would embark on an even more ambitious project as part of the "AIM alliance" to greatly expand its efforts to copy the original work Jobs had created at NeXT, emulating Microsoft's role as a duplicator rather than innovator.

Apple's internal factions splinter its competitive focus

Apple also initiated other efforts to remain competitive with NeXT, including an incremental advancement of the Mac's existing System 6 codenamed Blue and plans for an advanced new system named Pink. Blue eventually launched in 1991 as Mac System 7, which introduced support for QuickTime video editing and playback at a time when DOS PCs had trouble reproducing audio.

evolved into broad, nebulous research project that began rethinking the entire user interface (above), investigating the componentization of software with OpenDoc and conceptualizing new ways of working with network services and devices such as fax machines.

As Blue and Pink factions (and successive projects named Copland and the even more nebulous Gershwin) fought for attention and resources within Apple, the company was also still earning significant revenues from its older Apple II line, which fueled additional internal conflicts.

Source: OldComputers.net

Through 1993, it actively updated GS/OS for the Apple IIGS, which served as a sort of affordable Macintosh, incorporating a similar mouse-based, windowing interface. An earlier effort, Möbius, intended to develop an advanced Apple II model capable of emulating Mac software using a RISC processor designed by Acorn.

At the same time, conceptual work started on a new mobile device platform that would become Newton, an entirely new object oriented development system intended to power "Personal Digital Assistants" with a new user interface oriented around handwritten recognition and navigated by a stylus.

At the same time, portable PenLite tablet prototypes based on the conventional Macintosh architecture were also in development. Another parallel internal project known as Paradigm was also working on mobile devices, but rather than focusing on handwritten recognition, it was oriented around wireless communications and networking features.

Apple decided to keep Newton, shutter PenLite and spin Paradigm off in 1990 as an independent company named General Magic, which gained partnership investment from AT&T, Motorola, Matsushita, Philips and Sony. It eventually turned into a patent portfolio that was acquired by Microsoft to improve Windows CE.

Apple's revenues grow as Microsoft passes in profits

In 1990, Microsoft abruptly left its OS/2 partnership with IBM and shifted its resources toward marketing Windows to PC cloners on its own. The majority of Microsoft's revenues had always come from pre-bundled DOS licensing.

Zenith, then a DOS PC maker eyeing Apple's strong Mac sales to education, became the first company to pre-install Microsoft Windows on its new PCs in 1991, allowing it to advertise its hardware as a Mac alternative to schools.

Apple's hardware business, boosted by the release of profitable and innovative new PowerBooks in 1991, enabled the company's revenues to climb until 1995, but Microsoft's profitability began to surpass Apple in 1991. Unlike Apple, Microsoft didn't have have any overhead involved in engineering new hardware.

Microsoft's Windows licensing earned astronomical gross margins above 90 percent, while Apple's hardware margins were closer to 30 percent. Even in 2012, Apple's iPhone-fueled gross margins were around 42 percent while Microsoft's remained above 80 percent.

Further complicating Apple's ability to compete was the fact that it had been giving away free Mac System Software updates to its customers. When Apple tried to start charging like Microsoft, Mac users balked at paying anything to upgrade.

Apple's ARM partnership builds a new chip

While Microsoft was parasitically feeding on Apple's Macintosh, Apple was working to deliver its entirely new Newton handheld platform. Unlike the Macintosh, which greatly improved upon existing PCs by leveraging the readily available Motorola 68000 CPU, Newton needed an entirely new class of mobile CPU that didn't yet exist.

To develop one, Apple formed a joint partnership in 1990 with Olvetti, which five years earlier had acquired British computer maker Acorn.

Apple had earlier evaluated the Acorn RISC Machine processor for use in its Möbius project, but now it was interested in working with Acorn to optimize its simple but powerful and efficient desktop-class ARM processor for use in mobile devices, specifically to power the Newton Message Pad.

Apple wanted ARM to add an integrated MMU (memory management unit), but the struggling Acorn didn't have the funds to develop its desktop chip into the type of low power component Apple needed.

Acorn's existing, elegant ARM design formed the starting point for a new mobile architecture funded by Apple and built by Apple's California fab partner VLSI. Apple began using the first new generation of mobile ARMÂ chips, renamed the "Advanced RISC Machine," in the 1993 Newton Message Pad.

Apple initiates new technology licensing programs

Apple also embarked upon two new ways of selling its Newton technology: like Microsoft, it began licensing Newton hardware reference designs and the Newton Intelligence operating system to third parties, including Motorola, Sharp, Matsushita and Siemens, beginning in 1993.

A report by the Chicago Tribune cited Apple spokeswoman Tricia Chan as saying at the time, "Part of this new shift is because we are dealing with a whole new technology that will address multiple markets."

Chan added, "It does represent a paradigm shift of sorts for us. Only about 30 percent of Americans are computer literate, so by licensing this (stylus-based) technology, this will give us an opportunity to access the 70 percent who aren't."

The Motorola Marco (above) fused Newton with mobile wireless communication features, concurrent with the company's investment in General Magic in the Motorola Envoy, which lacked the Newton's handwritten recognition and thus much of its general magic.

Apple's joint partnership in ARM, Ltd. immediately became profitable in 1993. In addition to supplying chips to Apple and Acorn, ARM began licensing the rights to manufacture its chip designs, as well as offering an "architectural license" to companies interested in incorporating and modifying its core technologies in custom chip designs.

ARM's technology rapidly became the "Windows" of embedded and mobile chip designs, and Apple owned 47 percent of the company.

Apple joins the AIM alliance

While Acorn continued to use ARM's chips in its own desktop-class PCs, Apple announced another partnership in 1991 to work with IBM and Motorola in the "AIM alliance" to develop open technologies to counter Microsoft and its close partnership with Intel with the firmly established DOS PC, rapidly evolving into the "WinTel" platform.

AIM alliance members conceptualized scaling down IBM's POWER workstation-class RISC architecture to replace both Intel's decade-old x86 PC and Motorola's 68000 chips used in the Macintosh. Intel had already attempted to replace x86 with its own RISC chip, the i860, but its lack of compatibility with DOS and Windows marginalized it.

Apple began porting its Mac System 7 to new PowerPC hardware and developed a "Macintosh Application Services," or MAS layer to host new PowerPC Mac apps on IBM PowerPC AIX systems. Motorola planned to port Windows, while Jobs' NeXT, the BeBox and the Commodore Amiga also made plans to migrate to the new chip architecture.

While PowerPC was aimed at taking down Intel, the AIM partners also planned to deliver an advanced new operating system microkernel named Taligent, capable of hosting new object oriented frameworks, a product that sounded suspiciously identical to Jobs' NeXTSTEP operating system introduced three years earlier.

Microsoft's Bill Gates similarly announced plans to deliver exactly the same things in 1991 under the name "Cairo," a vaporware project that eventually delivered none of those things.

By 1996, Gates began describing the project as a vision rather than a real product, stating in an Computerworld interview, "Cairo is a futuristic system. It's something we're working on."

That vaporware vision helped derail the prospects for the much smaller NeXT, which had delivered a product ready to sell three years before Gates had even announced Cairo, and also distracted from the Taligent goals of the AIM alliance, which were also victimized by internal politics.

Macs on Intel, Unix, Clones

In 1992, Apple bizarrely launched a third (albeit secret) partnership with Novell, intended to port the Macintosh user environment to run on top of the DR-DOS Novell picked up when it acquired DRI, an effort intended to enable Novell to license a Mac-like product to sell on PCs as an alternative to Windows.

This "Star Trek" project necessitated porting the Mac user environment to Intel's x86 architecture, which was rapidly accomplished but then discarded by 1993 after the partners realized that all Mac apps would also need to be ported, a huge mistake Microsoft recently replicated with Windows RT.

In 1994 Apple recycled some of its efforts to launch the "Macintosh Application Environment," or MAE, which hosted the Mac desktop on top of Unix via X11, allowing Sun Solaris and HP workstations to run emulated 68000 Mac software. Apple portrayed MAE running the Mac environment on big iron Unix with a Sumo wrestler wearing a tutu.

Source: MAE.Apple.com via the Wayback Machine

In 1995, Apple launched a program to license the entire Mac OS to third party hardware makers. Apple offered reference designs in both 68000 and PowerPC versions, a strategy replicating its earlier 1993 program to license Newton hardware designs and software.

While chided for being initiated too late to compete with Windows, Apple's Mac Clones program was actually the result of a decade of attempts to port the Mac's user environment to other platforms, from its own Apple IIGS and A/UX to its partnership to deliver Taligent, MAS, StarTrek and MAE. Apple's Mac Clones program was actually the result of a decade of attempts to port the Mac's user environment to other platforms.

Apple's efforts to market the Mac and license its technology in various ways simply could not compete against the overwhelming market power Microsoft exercised with its own copy of Apple's Mac environment, a copy the courts sanctioned because of the 1985 licensing agreement Apple had signed with Microsoft in exchange for two years of Excel exclusivity on the Macintosh.

Following the loss of Apple's appeal in 1994 and the refusal of the Supreme Court to hear the case in 1995, Apple was largely portrayed as a washed up loser by the media, rather than as a hapless victim of an excessively broad interpretation of a poorly executed, vague intellectual property agreement from ten years prior.

Microsoft starts copying Newton, Palm

While the Macintosh had changed the world, Apple's Newton was so new that its price tag was simply too high to have a similar impact. It did, however, inspire similar products that advanced Apple's PDA concept toward today's smartphone.

Between 1992 and 1994, Microsoft launched its own "WinPad" vaporware to distract the market away from Newton, announcing partnerships with Compaq, Motorola, NEC and Sharp, but never releasing anything. Pulsar, Gates' pet project to create a wireless paging device, also never materialized.

In early 1995, Microsoft announced Pegasus. Two years later it released a new Handheld PC platform running Windows CE 1.0. The company avoided the term "PDA," which was by then associated with the functionality and sophistication of Apple's 1993 Newton, which Windows CE didn't even attempt to match.

The 1996 the Palm Pilot was introduced as a simpler, less ambitious personal organizer (below), but it also sold for about half the price of the Newton. It was powered by Motorola's Dragonball processor, a scaled down version of the Mac's 68000 chip.

Jobs canceled the Newton at Apple in 1998. That same year, Microsoft shifted its attention to Palm, renaming its HPC to Palm PC to cash in on Palm's branding and popularity. After getting sued by Palm, Microsoft changed the name to "Palm-sized PC."

Palm Pilots continued selling so well that despite bringing in just 10.4 percent of the revenue of Apple and less than 7 percent of Apple's profits in the second half of 1999, its early-2000 market valuation was an incredible $54 billion, 270 percent greater than Apple's $20 billion market cap.

Apple saved by Newton's ARM

Apple's Newton had only been moderately profitable. In 1997 the company spun it off as Newton, Inc., to independently manage and develop its licensing programs. However, as soon as Jobs took over as Apple's acting chief executive, he brought the company back inside.

After releasing another generation of products, Jobs terminated the product line and all licensing agreements the following year. Jobs also began harvesting the value of Apple's 42.3 percent ownership stake in ARM, Ltd., which floated an Initial Public Offering in 1998.

Jobs desperately needed to counter the media's incessantly negative portrayal of the "Beleaguered Apple Computer" and present the company as viable and profitable going forward. Jobs announced a $150 million investment by Microsoft, achieved as part of a cross licensing deal that dropped a pending $1.2 billion lawsuit against Microsoft and other patent claims potentially worth additional billions.

The media regurgitated a story of Microsoft's 1997 investment "saving" Apple, while ignoring Jobs' introduction of the deal, which clearly indicated the talks were motivated by a need to clear up "very serious" patent issues, not by an immediate financial crisis that could be prevented with $150 million.

By focusing on Apple's future prospects in working with Microsoft, Jobs directed attention away from millions of dollars in unsold inventory Apple subsequently wrote off as worthless for fiscal 1997, hidden within its losses of $1.045 billion despite Microsoft's supposed bailout 1/7 the size of that reported loss.

Apple then sold off that inventory at a discount starting in its 1998 holiday Q1, enabling the company to report a $309 million profit for fiscal 1998 despite revenues falling by more than $1.1 billion year over year. At the same time, Jobs also sold off 18.9 percent of Apple's ARM stock for $24 million, and Apple recognized another $16 million in stock appreciation from the IPO. Jobs' dumping of ARM shares was desperately needed to prop up Apple's performance at it struggled to regain its footing.

In fiscal 1999, Apple sold another $245 million of ARM stock, which made up about 40 percent of the $601 million in profit Apple reported.

In 2000 it sold another $372 million, accounting for 47 percent of its reported profits. In 2001, it sold another $176 million, which reduced its dotcom crash losses to just 25 million. In 2002 it sold another $21 million, making up 32 percent of its rebounding profits.

Finally, in 2003 it sold its remaining ARM holdings for $295 million, which erased what would otherwise have been $238 million in losses as Apple struggled in a weak economy. In total, ARM provided Jobs with a total cash infusion of more than $1.1 billion to pad Apple's profits and minimize its losses across five years as he rebuilt the company.

Jobs' dumping of ARM shares was desperately needed to prop up Apple's performance at it struggled to regain its footing, but in retrospect, it appears prescient when looking at ARM's historical stock price.

Source: Google Finance

The majority of Apple's ARM shares were unloaded just as ARM's shares temporarily exploded. Apple would otherwise have needed to hold them for the better part of the decade before they recovered to similar levels.

ARM provides Apple with the building blocks of iOS

Apple's 1990 ARM investment in the development of mobile technology paid off handsomely, not just in financing the company's late 1990s turnaround until it could recover on its own, but also in developing a rich vein of mobile components for Apple to begin mining in the 2000s.

Psion EPOC PDAs' early use of ARM chips contributed toward to the majority of mobile phones being ARM-based as EPOC gave birth to the Symbian partnership between Ericsson, Nokia, Panasonic, and Motorola in 1998. By 2002, overwhelming economies of scale favoring ARM motivated Palm to migrate its own Dragonball products to ARM.

These economies of scale made available a wide variety of ARM licensees to supply various components to Apple, from the CPU cores powering iPods and later iOS devices to WiFi chips and baseband processors incorporating specialized ARM microprocessors.

ARM, Ltd., licensed its technology to such Apple component suppliers as Broadcom, Cirrus Logic, Texas Instruments, Marvell, Qualcomm and Samsung, which supplied the primary ARM SoC components for iPod and later iPhone (above).

Historical ARM licensee Digital developed the StrongARM chips Apple used in later Newton devices. Digital's business briefly ended up under Intel's ownership, replacing the company's own ill fated i960 RISC with Intel's new XScale ARM brand. After investing around $5 billion to turn the unit into a viable mobile competitor to TI, Intel sold it off to Marvell in 2007 for just $600 million, just as Apple launched the iPhone.

That sale left Intel stuck with trying to shoehorn its own x86 architecture into the mobile market with Atom chips, which Apple passed over in 2010 in favor of its own A4 ARM design when it released iPad.

Apple's iPad immediately triggered the subsequent collapse of netbooks and contributed to the rapid erosion of WinTel PC sales that the AIM alliance failed to do twenty years earlier.

Apple's blockbuster success in selling iPhones and iPads not only decimated PC sales, but also destroyed the profits of less innovative smartphone makers, who responded by filing legal claims against Apple, triggering the iPhone Patent Wars, which the next segment will detail.