While efforts by Apple and Samsung to enforce their respective patent rights are often equated as back-and-forth arguments among twin giants who irrationally refuse to settle their legal disputes rather than innovate and compete in the market, there's a vast difference between the legitimacy of their respective intellectual property claims and what each company is demanding.

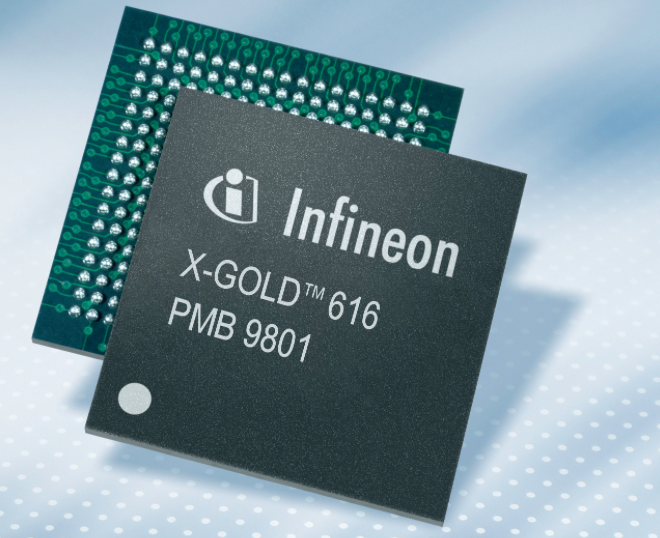

Source: Infineon

The $11.72 Infineon baseband chip targeted by Samsung's patent claim

The "patent infringement" that Samsung asserted in order to win its original (now vetoed) U.S. import ban against certain GSM versions of Apple's iPhone 4 and iPad 2 models isn't a matter of Apple scandalously copying technology that Samsung invented, and then refusing to pay Samsung for the use of it.

Samsung claimed infringement of a radio technique implemented in low level code and related to the GSM / UMTS 3G networking standard. That code was sold to Apple as part of a finished product, embedded in the PMB9801 baseband chips (shown above) it purchased from Infineon to solder into the logic boards of its iPhone 4 (shown below) and iPad 2.

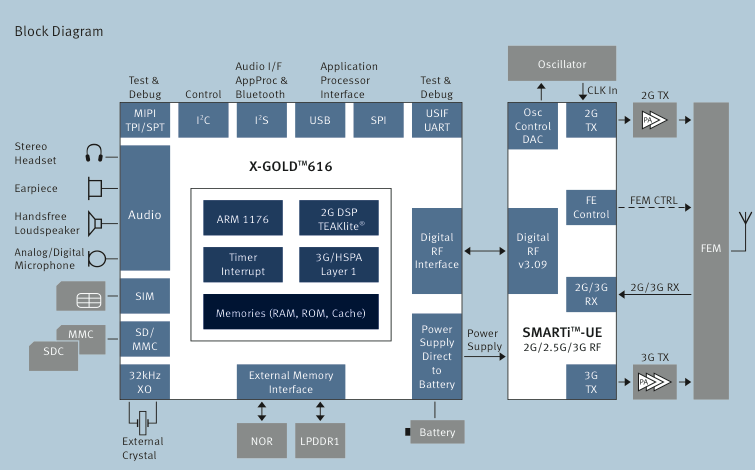

On the iPhone 4 and iPad 2 models Samsung was targeting, Apple's iOS runs the A4 Application Processor (AP) while a second, embedded operating system (Nucleus RTOS, sold by Mentor Graphics) runs the Baseband Processor (BP). The two chips communicate like a PC connected to an external modem via a serial cable.

The Application Processor is the main SoC, such as the iPhone 4's A4, which incorporates an ARM CPU core, a PowerVR GPU core and additional integrated logic. This "brain" also has RAM attached to it externally.

The Baseband Processor is a computer unto itself which handles the device's mobile radio and analog audio processing (diagramed below). On the GSM iPhone 4 and iPad 2, this is Infineon's PMB9801, branded as "X-GOLD 616" and identified as 337S3833 on the chip itself. It has its own ARM microcontroller, RAM and integrated ROM firmware and talks to the AP, the antenna's radio chip and the SIM card.

In 2010, iSuppli estimated the iPhone 4's A4, which is manufactured by Samsung, to cost $10.75, while it estimated its Infineon baseband chip to cost $11.72.

Every year, Apple's mobile devices get a new generation of more powerful and capable chips. While Apple has called attention to the AP, beginning with the A4, followed by the A5 in iPhone 4S featuring dual core CPUs and dual core GPUs and the A6 in iPhone 5 with custom, dual "Swift" core CPUs and triple core GPUs, the BP also gets a big upgrade every year.

For example, the new baseband chip in iPhone 4S enabled it to jump from a maximum 7.2 Mbps HSDPA in 3G data downloads to 14.4 Mbps HSDPA, while iPhone 5 introduced a baseband chip capable of 42 Mbps DC-HSDPA.

Samsung demanded $16 for patents already licensed within a $11.72 chip

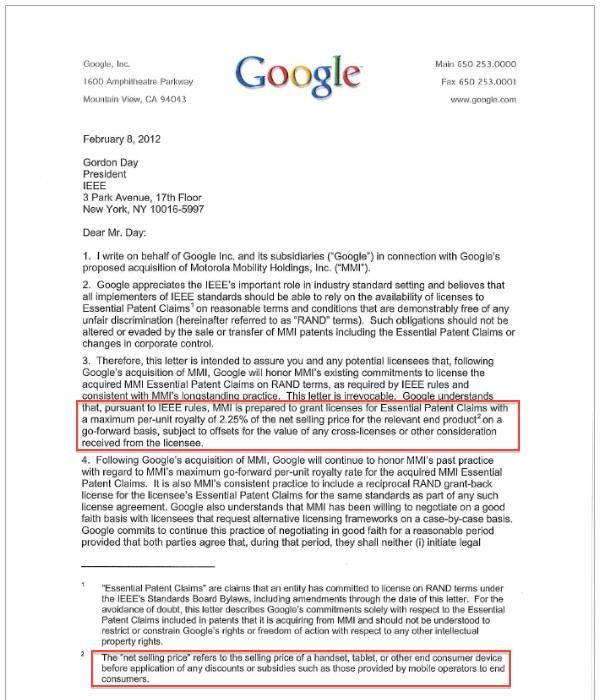

In its hardball negotiations with Apple last year, Samsung demanded a 2.4 percent royalty to cover the use all of its Standards Essential Patents (SEPs) pertaining to 2G/3G GSM/UMTS technologies used in the baseband chip.

Apple had a few problems with this, as noted in an April 30, 2012 letter from Apple's intellectual property licensing director Boris Teksler, addressed to Seongwoo Kim at Samsung, released during the trial last fall and published by Florian Mueller of FOSS Patents.

First, it disputed whether Samsung's SEPs were even valid. Second, it doubted whether they were even in use within the components it was buying. Third, the baseband components Apple was buying, initially from Infineon and later Qualcomm, had already licensed Samsung's technologies on behalf of their customers.

This "first sale" doctrine means that if you buy a product from a company that has legitimately licensed the use of the technologies it employs, the original patent owner can't go "double dipping" and demand more patent royalties from the end user, just as a landowner can't lease their property to a hotel chain, then come back and demand rent from anyone who comes to stay there.

Most egregiously, however, Samsung wasn't just demanding a double-dipping royalty for questionable patent claims on the baseband chip. It was demanding a royalty percentage of the full retail price of the finished product. With an average selling price of $660 in 2012, that amounted to around $15.84 per iPhone and iPad Apple was selling.

"Can Samsung provide Apple with any evidence of any company paying Samsung a royalty similar to the 2.4% of ASP [Average Selling Price] terms that Samsung has requested from Apple?" Teksler asked in the letter.

An even larger $18 figure was cited by the LA Times as being the amount Samsung was asking from Apple per device, apparently connected to 2.7 percent rate Samsung had earlier asked.

With Apple's annual sales of over 180 million affected devices in 2012, those figures would amount to between $2.7-$3.2 billion for Samsung SEP licensing fees, a figure that would go up every year. With that much money on the line, Apple was prepared to fight Samsung in court if it refused to negotiate a more reasonable rate.

The problem with paying Samsung insane fees for invalid patents that were already licensed

Apple also knew that if it had agreed to such an insane demand from Samsung, the floodgates would open and everyone who could lay claim to a technology that might be in use within any one of the components installed in any its products would start demanding a second scoop of huge fees of their own. Nokia already had started similar demands in late 2009, and HTC and Motorola were also in line for a fat cut of Apple's iPhone profits.

With gross margins of around 40 percent, it would only take 16 patent trolls lining up at the trough demanding the same 2.4 percent cut to turn Apple from the most profitable company in smartphones into a Motorola Mobility. Further, Samsung didn't even represent 1/16 of the intellectual property appearing on the baseband chip.

The code that Samsung claimed its patent related to amounted to "far less" than 1/100th of what was installed on the baseband chip. Remember, this wasn't even Apple's code; it was embedded on a finished product, and the related patents had already been licensed for resale by Infineon.

Dr. Nils Rydbeck, former Chief Technical Officer at Ericsson, testified in a related case that Samsung was demanding similar amounts of money for SEPs related to what he called "trivial functionality" within the UMTS stack.

He was cited in a report by FOSSPatents, where he explained, "in total, the accused portion of the UMTS standard accounts for about 0.0000375% of that standard. [...] And Samsung only contributed to a portion of that 0.0000375%. [...] That technology is a relatively unimportant portion of the UMTS standard that has not received any significant mention in the press or other publications regarding the UMTS standard."

On top of that, Samsung's huge royalty demands only covered patents related to 2G/3G UMTS. Samsung hoped to return for another huge helping to cover any patents related to 4G LTE.

In report by the Korean Times that appeared immediately after Samsung lost in court last fall, the company said it plans to not only appeal the jury's findings of its willful infringements, but also to pursue new patent litigation related to 4G LTE networks.

The paper stated that "Samsung confirmed that it will immediately sue Apple if the latter releases products using advanced long-term evolution (LTE) mobile technology," despite the fact that Apple already had released the iPad 3 with 4G LTE six months earlier.

With FRANDs like these, who needs enemies?

In its letter to Samsung, earlier this year, Apple also questioned Samsung's hypocrisy in demanding rates that were 626 percent to 880 percent more than Samsung itself was willing to pay in its own FRAND patent cases.

Teksler wrote, "Samsung's demand would imply approximately a 44% aggregate royalty burden on UMTS products. This is far above the 5-7% range that Samsung argued (in its earlier litigation with Ericsson and InterDigital) was the appropriate range for aggregate royalties."

Apple stated that it was willing to pay Samsung FRAND rates for its UMTS portfolio, comparable to what it paid to license technologies like H.264. However, it was only prepared to pay a total of 5-7 percent royalties for baseband chip patents, and only on the value of the chip itself. Samsung's share of those total royalties would have to be proportional to its contribution. In return, Apple would offer Samsung a reciprocal arrangement on its own UMTS patents. Samsung didn't like any of this.

"Apple is willing to license its declared-essential UMTS patents to Samsung on license terms that rely on the price of baseband chips as the FRAND royalty base, and a rate that reflects Apple's share of the total declared UMTS-essential patents (and all patents required for standards for which UMTS is backward-compatible, such as GSM)— provided that Samsung reciprocally agrees to this same, common royalty base, and same methodological approach to royalty rate, in licensing its declared-essential patents to Apple," Teksler wrote.

Rather than negotiate reasonable licensing fees, Samsung began a world tour of simply testifying in various jurisdictions that it "had offered to negotiate with Apple to license the patents on fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory (FRAND) terms," according to a report by MacWorld.

“Our position is Apple has refused to engage in negotiations," Samsung attorney Neil Young was cited as telling the court in Australia.

Samsung was banking on being able to shakedown the entire industry, leveraging the value of its UMTS patent portfolio along with another weapon that appeared very promising: ITC import bans. Rather than dragging everyone into court, Samsung thought it could simply file cases alleging infringement of various patents and obtain import bans that would kill its competitor's capacity to sell anything until they agreed to whatever terms Samsung could invent.

Samsung had already observed other companies making broad demands covering their own patent portfolios. Google and Motorola initiated plans to sue everyone over H.264 patents, demanding similar 2.24 percent royalties on the entire cost of any device that made any use of them. For example, Motorola launched an effort to shakedown Microsoft for 2.24 percent of, not just Windows, but the full retail value of any finished PCs sold with Windows.

Microsoft was also on its own patent licensing expedition, hoping to make up for the failure of Windows Phone by shaking down Android licensees to pay for its mobile patent portfolio. Samsung had already signed up to pay Microsoft licensing fees for Windows Phone, so it decided to agree to pay it for Android licensing as well.

And now that Apple was asking for steep licensing fees to cover Samsung's appropriation of its iOS devices, Samsung expected to be able to similarly monetize its own patent portfolio. Additionally, Samsung wanted Apple to throw in a full license to its entire patent portfolio, not just wireless patents. That was a sticking point because Samsung had little of value to offer in return.

Samsung's worthless patents

Due to its history as a component and featurephone manufacturer, Samsung didn't have many valuable smartphone user interface, operating system or device design patents, but it did have patents on lower level mobile radio and other component-related technologies.

However, Samsung was also manufacturing many of the components in Apple's iPhone and iPad, including its AP, DRAM and flash memory, parts accounting to over $50 of the total $187.51 bill of materials estimated by iSuppli.Samsung therefore had to focus on the patents it could allege against the technology in one of the parts it wasn't already suppling Apple with: the baseband chip.

Samsung therefore had to focus on the patents it could allege against the technology in one of the parts it wasn't already suppling Apple with: the baseband chip. Most of the patents Samsung asserted in the U.S. case, and in the more than 50 lawsuits worldwide raging in at least 9 different countries, are related to 3G UMTS technologies built into the baseband.

That includes patent 7,362,867, which Samsung almost successfully used to block sales of Apple's older products in the ITC case last week.

If the Obama administration hadn't intervened, Samsung's import ban wouldn't have stopped sales of Apple's modern iPhone and iPad, but it would have disrupted Apple's operations and taken away the cheapest iPhone option on AT&T, a carrier that, according to Kantar, is already pushing more entry level Android phones to new smartphone users than it is iPhones.

Why Samsung's 7,362,867 patent only targeted older devices

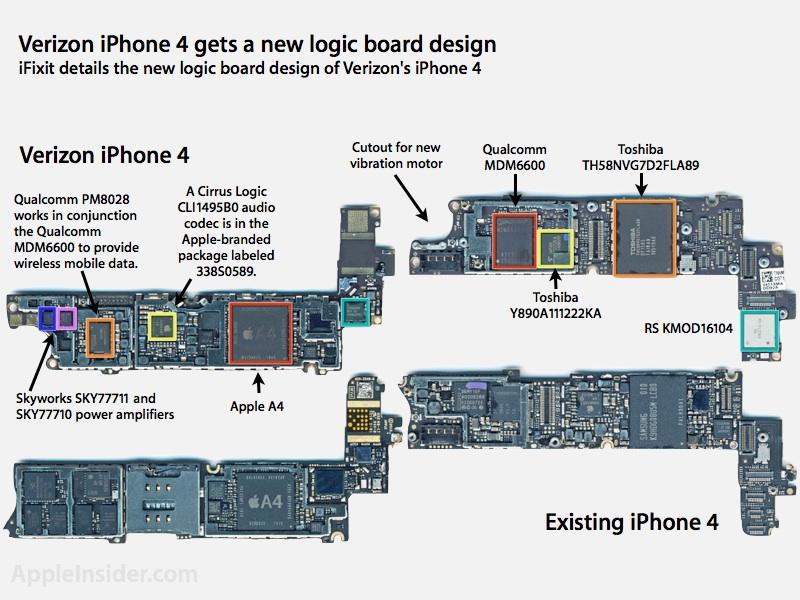

Apple had been using Infineon's family of baseband chips since the iPhone first shipped in 2007. Infineon was acquired by Intel in August 2010. Immediately afterward, word leaked that Apple was planning to ditch Infineon's chips for Qualcomm baseband components instead, which it did the next spring.

While this was initially interpreted to be related to supposed problems between Apple and Intel (which haven't materialized since), in retrospect it's crystal clear why Apple made the switch: Qualcomm supported CDMA cellular networks and Infineon didn't.

In order to produce an iPhone 4 model that could work on Verizon Wireless (which subsequently launched February 2011), Apple needed a baseband chip capable of CDMA as well as UMTS used by AT&T and other GSM carriers worldwide. The solution was Qualcomm's MDM6600.

Support for CDMA also allowed Apple to eventually sell an iPhone 4/4S to Sprint and Japan's KDDI (October 2011) and on the CDMA portion (i.e. the vast majority) of China Telecom's network, which was first served by a specialized new CDMA version of iPhone 5 in December 2012.

Samsung had originally filed patent '867, for "a scrambling code generating apparatus of a downlink transmitter in a UMTS mobile communication system," in 2000. It was granted in 2008, but Samsung only began alleging infringement by Apple in 2011, in response to Apple's suit against it.

The ITC import ban Samsung initiated (separately, in parallel to Judge Koh's U.S. Federal Court case) only managed to successfully allege infringement by Apple of '867 on products using Infineon chips, which Apple had begun phasing out the previous fall in a move toward a "global" iPhone compatible with CDMA networks.

Apple's shift to Qualcomm baseband chips fortuitously limited the potential fallout of the ITC ban that was eventually granted in June 2013, before being vetoed over the weekend prior to the first business day when the ban was slated to go into effect.

The most insane part of the ITC ban

Apple wasn't forced to stop using the UMTS technology Samsung had patented. Qualcomm, the vendor of Apple's current baseband chips, had licensed the use of the patent from Samsung. The ITC recognized that this "exhausted" Samsung's ability to sue Apple for "using" the patent on modern devices with Qualcomm chips. Samsung managed to convince the ITC that Infineon's license was no longer valid once Apple bought the chips and began using them.

But Infineon had also licensed Samsung's patents. The difference was that Samsung managed to convince the ITC that Infineon's license was no longer valid once Apple bought the chips and began using them.

To do this, Samsung invented a specious legal argument that insisted that, despite Infineon having a legitimate license to Samsung patents, and despite Intel, which had bough Infineon, also having secured a license to Samsung's patents, and despite having signed agreements with a UMTS standards body that barred it from being able to arbitrarily revoke its license in order to extort higher licensing fees, that it could revoke its license anyway and insist that Apple had to pay, not just FRAND licensing fees, but anything Samsung could imagine, a veritable blank check.

And if Apple refused to give Samsung whatever it demanded, Samsung would tell everyone that Apple was refusing to pay licensing fees and refusing to negotiate while also publicly insisting that Apple was "infringing its patents."

Samsung somehow managed to convince the ITC that Intel's license was only valid in the United States, and that Intel's American sales of Infineon chips to Apple in California was not a transaction it recognized to be in the United States.

Writing about the ITC's decision, Groklaw gleefully reported last October that Administrative Law Judge E. James Gildea had "utterly and definitely rejected Apple's FRAND allegations and completely exonerated Samsung."

The full text of the ITC's bizarre stance in support of several egregious Samsung patent abuse issues is only overshadowed by the premature celebration by Groklaw to its Android-community audience over the prospect that Samsung might get away with not just stealing Apple's work, but could even use sales injunctions as a way to further abuse the patent system in an effort to extort billions in exchange for worthless patents that have already been sufficiently licensed.

That's still not the crazy part yet.

When Apple filed its first U.S. Federal Court complaint against Samsung in April 2011 (alleging infringement of 3 technology patents and 4 design patents), Samsung returned fire with five patents of its own. By October, the list had ballooned on both sides to include 26 different Apple patents and 17 for Samsung, prompting Lucy Koh, the judge overseeing the battle, to demand both sides narrow their cases significantly.

Judge Koh was also throwing out some claims entirely, issuing summary judgments of non-infringement of asserted patent claims on both sides. Among the patents thrown out as obviously non-infringing was Samsung's 7,362,867 patent. It was thrown out last summer.

This weekend the industry watched with tense anticipation to see whether the U.S. President would intervene to stop an import ban on a patent Samsung knew was invalid for the last year. And in response, Samsung stated:

"We are disappointed that the U.S. Trade Representative has decided to set aside the exclusion order issued by the U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC). The ITC's decision correctly recognized that Samsung has been negotiating in good faith and that Apple remains unwilling to take a license."

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

-m.jpg)

Bon Adamson

Bon Adamson

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

-m.jpg)

129 Comments

First degree extortion by Samsung should come as no surprise. There should be laws against that. Samsung is crooked to the core... http://news.cnet.com/8301-13578_3-57571837-38/samsung-hires-judge-who-ruled-against-apple-as-legal-expert/ How the ITC blew it... http://tech.fortune.cnn.com/2013/08/05/apple-samsung-itc-pinkert/?source=yahoo_quote Not a single drop of dignity in Samsung.

"... who irrationally refuse to settle their legal disputes rather than innovate and compete in the market,..." Apple is inventing and reinventing. Samsung copies and adding features. There is a vast difference between two.

Nice write up but the fact still remains the ITC found Apple guilty of infringing on the patent. So did the ITC not have all of the facts listed? I would really hate too believe a governing body like the ITC acted Willy Nilly. I also really don't like to see the leader of a country overturning it's own courts, what's the use of having them when all it takes is a veto to overturn them. I don't know, I'm just asking, is this normal in America? When Apple and Samsung tried to sue each other in our court systems both were denied. That and it's really not worth suing here as we cap the damages to 200,000 for suffering and payment of property for individuals and I think 1,000,000 for damages plus the amount of proven revenue lost for company's. Big reason why Swiss Rail would have sued in America if not for the settlement.

[quote name="poksi" url="/t/158880/samsungs-vetoed-push-for-an-itc-ban-against-apple-inc-in-pictures#post_2373974"]"... who irrationally refuse to settle their legal disputes rather than innovate and compete in the market,..." Apple is inventing and reinventing. Samsung copies and adding features. There is a vast difference between two.[/quote] Well yes Samsung has lost patent suits in America and Germany(later overturned) but were thrown out in UK, Japan and Korea. Samsung also has 20 times the amount of patents filed then Apple. So it's all about prospective, in the US yes Samsung might seem like nothing but a cheap rip off artist, the rest of the world, not so much.

The baseband processor doesn't live in isolation. It needs to talk to the application processor and it's therefore possible for a manufacturer to infringe on low-level comms from the AP side. The chip's patent license almost certainly doesn't cover any software written by Apple on the AP side. How likely an infringement is on the AP side really depends on the baseband processor though. Some baseband processors talk to the AP at a very low level, others (especially those from Qualcomm) hide a lot of the complexities and data structures from the AP. How would Samsung ever know though? It must have been 100% guesswork on their part.