As Apple and Google work to build out a so-called "Exposure Notification" API and accompanying operating system-level assets to help monitor the spread of COVID-19, health experts argue the companies' overly stringent privacy policies will render the solution useless out of the gate.

Experts in the field, including those currently building digital contact tracing apps for government health authorities, expressed concern about the Apple-Google system in Friday expose published by The Washington Post.

Specifically, officials are concerned about data sharing restrictions that are baked into the Exposure Notification API. Without access to geolocation data and other important user information, public health agencies building apps on the framework are at a disadvantage, some experts say. Further, Apple is preventing access to iPhone's Bluetooth communications stack, meaning contact tracing apps are forced to run in the foreground to be effective.

Though they decry the Apple-Google solution, it appears that interviewed experts have little to no knowledge of how the system is designed to function.

For example, Helen Nissenbaum, a professor of information science and director of the Digital Life Initiative at Cornell University, called the companies' leveraging of consumer privacy in defence against PHA access to smartphone technology a "flamboyant smokescreen." Nissenbaum said it was ironic that two tech firms who "for years tolerated the mass collection of people's data" are now preventing access to information that could be vital to public health, according to the report.

"If it's between Google and Apple having the data, I would far prefer my physician and the public health authorities to have the data about my health status," Nissenbaum said. "At least they're constrained by laws."

Apple and Google have consistently positioned user privacy as a guiding feature of the Exposure Notification platform, an asset that the companies contend will lead to greater adoption.

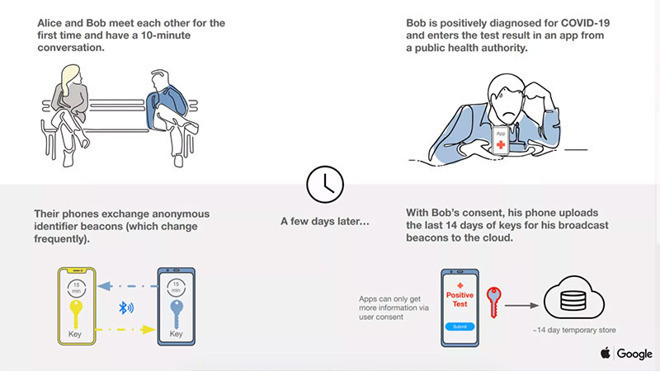

The system does not store data on central servers run by Apple or Google, but instead silos anonymized Bluetooth beacons -- contact information -- on user devices until participants elect to share the information with an outside party. If and when a user is diagnosed with COVID-19, they can opt to upload a 14-day list of recent contacts (again, anonymized) to a distribution server, which matches beacon IDs and sends out notifications alerting those individuals that they came in close contact with a carrier of the virus. Doctors can also peruse the data, if such access is granted.

Indeed, governments have bemoaned Apple and Google's reluctance to store Exposure Notification data on centralized servers, a decision made in part to protect sensitive information and in part to prevent potential mission creep. Britain's NHS, for example, is testing its own contact tracing app with a centralized data storage scheme. Without Apple and Google's help, however, the system has encountered problems.

Matt Stoller, director of research at the American Economic Liberties Project, is another critic quoted by The Post.

"They are exercising sovereign power. It's just crazy," Stoller said, adding that Apple and Google have "decided for the whole world that it's not a decision for the public to make. You have a private government that is making choices over your society instead of democratic governments being able to make those choices."

Both Apple and Google are operating within strict telecommunications and trade regulations and offer the COVID-19 tracking initiative as a service to customers. Here, Stoller does not seem to have a base understanding of the technology industry or the apparatus that controls it. He appears to be advocating for an alternative that would, by proclamation, enlist the companies to open aspects of iOS and Android to overarching government oversight.

The report also mentions North Dakota's efforts to augment traditional contact tracing programs with digital logs stored on a user's smartphone. State officials initially hoped the Apple-Google solution would provide a boost to the app, but restrictions have prompted developers to start from scratch. Instead of a single piece of software, the state is building one app for contact tracing teams and another that integrates the Exposure Notification API.

"Every minute that ticks by, maybe someone else is getting infected, so we want to be able to use everything we can," said Vern Dosch, contact tracing liaison for North Dakota. "I get it. They have a brand to protect. I just wish they would have led with their jaw."

The report goes on to suggest that, despite causing issues for PHAs, the privacy protocols might be for naught. Some health officials, like assistant professor of medicine at the University of California at San Francisco, Mike Reid, are dubious that tech companies can maintain high levels of privacy protection. Reid is training contact tracers in California.

"We go to pains to minimize the amount of data we take from people and we ask consent from people we're talking to on the phone. We go to considerable lengths to ensure there are strong technical controls to ensure the anonymization of our platforms," Reid said. "Can you say the same thing about these big tech companies? I'm not sure."

Distilling the complexities, and perhaps misunderstandings, surrounding the Apple-Google initiative is a somewhat contradictory statement from former chief technologist of the Federal Trade Commission, Ashkan Soltani.

"We've overcompensated for privacy and still created other risks and not solved the problem," Soltani said. "I'd personally be more comfortable if it were a health agency that I trusted and there were legal protections in place over the use of the data and I knew it was operated by a dedicated security team."

Apple and Google released initial APIs for their Exposure Notification system in late April ahead of a public launch expected for mid-May.