The iPhone 14 Pro has a new segmented Adaptive True Tone flash that can adapt to a camera's focal length. Here's how a small change helps photography.

The iPhone 14 Pro and iPhone 14 Pro Max received the lion's share of updates from Apple in the 2022 refresh. As usual, along with introducing things like the always-on display and crash detection, Apple made considerable changes to the camera.

However, while most of the attention landed on adding a 48-megapixel camera and the Photonic Engine, Apple used its event to briefly mention a more minor but quite significant change -- Apple updated the camera flash too.

While Apple continues to use the tried and tested True Tone flash in the iPhone 14, it has switched to what it calls an Adaptive True Tone flash. As explained by iPhone product manager Vitor Silva during the presentation, the new flash has a "new adaptive behavior based on the focal length of the photo."

In plain terms, it has updated the flash to change how it fires based on how zoomed in or zoomed out the camera is when it's taking a photograph. If it's zoomed in, it will concentrate the light with minimal spread to the sides, while for wide-angle shots, it will spread the light out as wide as possible.

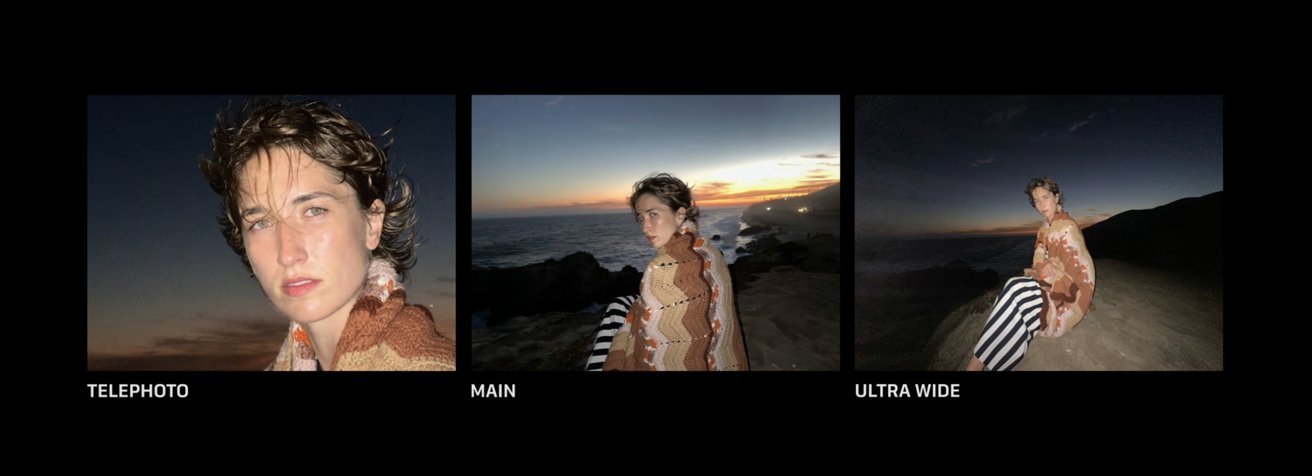

Apple demonstrated the Adaptive True Tone flash during its September 7 event.

The iPhone camera also does this while making the light as uniform as possible, spreading that light as evenly as it can.

What Apple has done with the flash is something experienced photographers have used for quite a few years already. It follows the same principle in different ways.

Speedlites and light management

Flashes come in all shapes and sizes, but they all have the same task: casting light in a specific direction for a particular period of time. At the same time as dealing with how light is emitted at a subject or background, the photographer also has to manage where the light doesn't need to illuminate at all.

To explain what Apple's doing, it's best to consider the speedlite. A speedlite, generally speaking, is a cheap and compact flash that can be an essential tool in a photographer's collection.

An example of a speedlite, a compact flash used by photographers.

The top half of the speedlite is the flash head, which consists of an empty tube that contains the main flash unit. At the top is a lens with a pattern of ridges, used to control how light exits the flash, including how light falls off toward the edges.

Notably, the flash isn't fixed in place. The flash element can move back and forth inside the chamber, from almost touching the front lens to as far back as possible inside the device.

The movement of the flash, referred to as "zoom," is somewhat similar to that of a camera's zoom.

At a low zoom level, such as 20mm, a camera would take a wide shot, and a speedlite would disperse its light over a wide area. Likewise, 200mm would be a telephoto or zoomed-in photograph on the camera, while the flash would narrow the light coverage to match.

You can see the flash element when it is close to the lens on a speedlite.

The 20mm wide zoom level positions the flash element very close to the lens to spread light as much as possible. At 200mm, that same element is far from the lens, so light is directed more directly forward.

To see this effect for yourself, shine a small flashlight through a tube, with the bulb close to one of the ends, then as far back so it has to shine through the entire tube length. As the torch bulb descends the tube and further away from the opening, you'll see the spread where the light exits the tube narrows down.

For photographers, the speedlite's bulb intensity on the photo target is a known quantity and doesn't change through any other effect than the positioning of the bulb. Along with the duration it's lit, photographers can manage the light's zoom or coverage area.

The iPhone 14 Pro's flash has the same ultimate result of shaping the light to match different levels of zoom. However, it goes an alternate route.

Same concept, different technique

The technique used by speedlites requires the flash to travel back and forth from the lens and the opening. This is not an option for an iPhone, which has to share its 0.31-inch depth with other elements like a display.

Since it cannot move the light source to change how it covers an area, Apple used what remained to pull off a similar trick. It managed the light source itself and the lens.

The easy bit is the lens assembly since it's built and fixed in place. Apple had to settle on a design that could handle light in a specific way, depending on the position where the light shines from.

Apple's Adaptive True Tone flash uses multiple lenses and nine LEDs.

During the event, Apple hinted that it was a multi-part lens, with the outermost layer looking like a Fresnel lens. This is a ridged circular design used in many applications, including torches, spotlights, and lighthouses, to focus the light in a narrow or defined coverage area.

The trickier bit is the light, as Apple had to alter how the light shines through the lens assembly to create different zoom levels without physically moving it.

To accomplish this, Apple uses an array of nine LEDs below the lens stack in a three-by-three grid. The power of each LED can be individually adjusted and individually fired, enabling Apple to use the grid to create light patterns.

The different segments of the LEDs shine light through different parts of the lens stack and illuminate whatever it is shining on in different ways. In effect, by controlling the pattern that the LEDs fire, Apple can control the light from the flash, shaping it to better fit different levels of zoom.

Firing the large central LED on its own results in a relatively narrow beam of light exiting the flash, making it ideal for telephoto shots. Mid-range zoom can be created by firing the mid-sized LEDs in the center top and bottom, and middle left and right positions.

Lastly, firing all eight outward edge LEDs but not the central one produces a flash for wide-angle shots.

LED patterns vary the light output of the iPhone 14 Pro's flash.

Apple likely has more patterns in use than what's shown, but it's also demonstrated restraint. The wide-angle shot uses all LED segments, except the middle, on purpose.

This is because it adds a bright and focused beam of light that will affect the center of the photograph alone. That part of the image could end up being overexposed simply from the bright flash in that area.

Leaving the middle LED off for a wide shot means the surrounding LEDs can work together to create a more even image. As Silva said on stage, the flash now provides "up to three times better uniformity compared to our previous generation."

Using so many LEDs also plays into the claim that the flash can be "up to twice as bright" as the previous version. But, since Apple controls the intensity, it may not necessarily use full power for the LEDs that often.

Apple could have gone down the lazy route and used a brighter or bigger LED flash instead of going to all this extra engineering effort. Instead, Apple went the tougher road and came up with a design to give the flash results it wanted to provide its users.

It may not get as much attention as a 48-megapixel sensor, but it's a welcome feature for photographers that need just a bit of illumination for a late-night shot.