There are a lot of hidden files and folders in macOS, which you can still access if you know the method. Here's how to see the invisible files.

Hidden files in macOS Ventura

There's a lot of additional functionality beyond basic Finder use. Mac users love their machines for their clean, simple design, ease of use, and minimalist UI, but underneath all that elegance is a full-blown powerful UNIX operating system.

UNIX was invented at Bell Labs in 1969 and was originally designed to run on mainframe computers with time-sharing terminals. In 1997 when Steve Jobs returned to Apple, the company decided to transition the Mac to a new modern UNIX-based system based on the NeXTSTEP OS, which was developed at Steve's other company NeXT.

NeXTStep and Mac_OS_9 were combined to create Mac OS X, which Apple shipped in 2000 - now simply called macOS.

The original UNIX filesystem was complex, containing hundreds of directories, thousands of small programs, and a variety of other tools, including a terminal shell and scripting languages -- nearly all visible and routinely accessible to the user.

Today on macOS, most of the original UNIX system is still present but hidden away from the user, who rarely needs to see it.

There are various reasons why you might want to view the invisible parts of the filesystem on your Mac. These include installing 3rd-party UNIX tools, installing developer tools and packages, changing login scripts, removing hidden preferences, or removing files installed by macOS 3rd-party installers.

You might also want to hide files and folders in invisible locations for security reasons.

Before we dive into how to show all invisible files on your Mac, be aware that moving, deleting, or renaming invisible parts of the filesystem can render your Mac unbootable, so proceed with caution. Accessing invisible parts of the OS is not recommended unless you know what you're doing.

Toggling Invisible Files in Finder

The simplest and easiest way to toggle invisible files on or off in the macOS Ventura Finder is to press the Command-Shift-period keys simultaneously.

You can also open a Terminal window and type:

defaults write com.apple.Finder AppleShowAllFiles true

Afterwards, press Return. This tells the Finder to show all files on the filesystem.

You will need to restart the Finder for the changes to take effect. To do so you can either Force Quit and Relaunch the Finder in the Force Quit window from the Apple menu, or you can right-click or Control-Option-click the Finder icon in the Dock and select "Relaunch" from the popup menu.

When you force quit the Finder, any running Finder operations, such as file copies, will be immediately canceled.

In Terminal, you can toggle invisible files off later with the same Terminal command but with the value set to false:

defaults write http://com.apple.Finder AppleShowAllFiles false

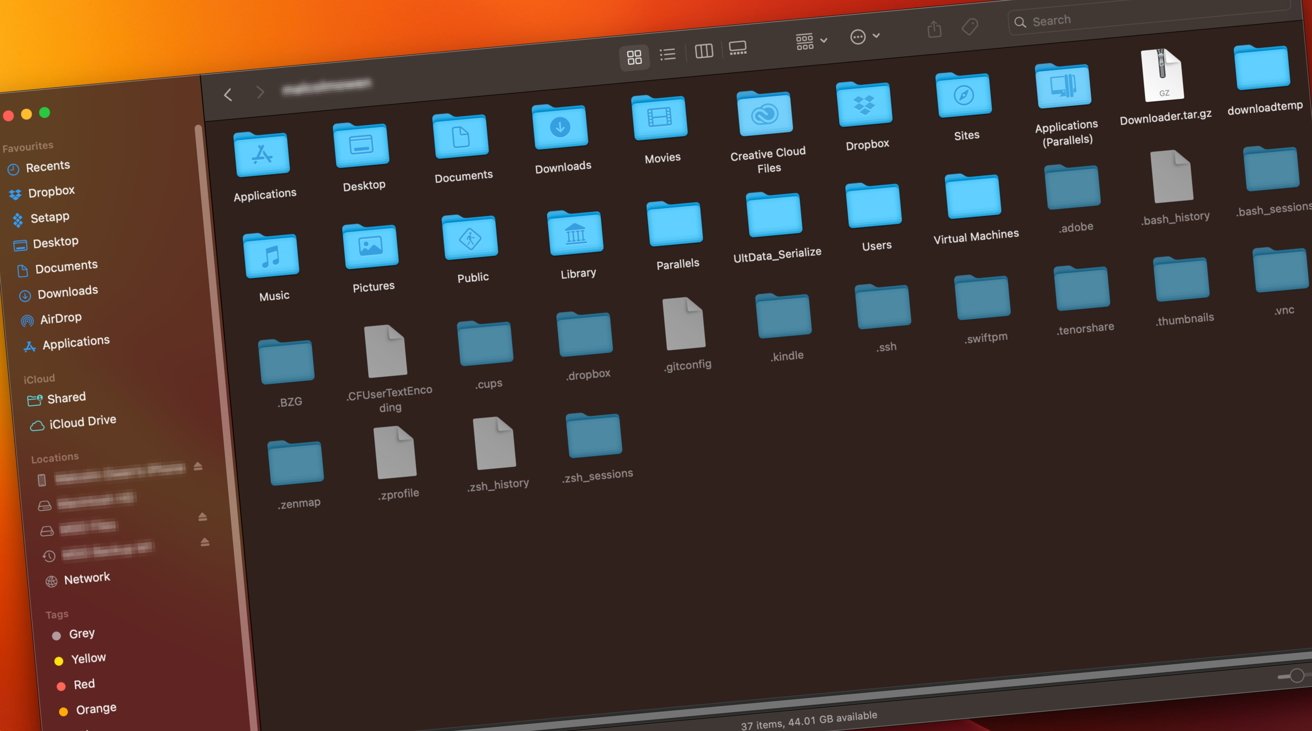

Once you've shown invisible files and relaunched the Finder, you now have full access to all parts of the filesystem on all mounted volumes on all storage devices on your Mac.

The version of UNIX macOS is based on is called Berkeley Sockets Distribution, which itself was a merger of AT&T System V UNIX and a TCP/IP socket layers developed at the University of California Berkeley in the early 1980s. When NeXT was developing NeXTStep, it chose FreeBSD as the core of the system because of its networking capabilities.

When Apple bought NeXT in 1997, it modified the core OS slightly and called it Darwin - which is still the basis of macOS and iOS today. At their cores, these OS'es are full, powerful UNIX systems. Darwin is full-on UNIX.

If you open your Mac's Startup Disk, after showing invisible files, you'll see additional folders beyond the standard Applications, System, Library, and Users folders.

The key invisible folders are:

- bin

- etc

- sbin

- tmp

- usr

- var

Apple chose to move 3 of these folders (etc, tmp, and var) into a new folder called private.

Hence the etc, tmp, and var folders at the root of your Startup Disk are really just aliases. Most single-file UNIX binary tools are stored in bin, sbin, or usr/local/bin, or in usr/local/sbin

To confuse matters more, there are also usr/local/etc and usr/local/var directories.

There are 3rd-party Mac UNIX tools managers such as Homebrew, which manage the installation/removal of additional 3rd party UNIX tools into these locations for you.

There is also the traditional UNIX home folder at the root of your Startup Disk, but in macOS, it's not used as in most other UNIX systems because Apple decided to move the home folders for all local users to the macOS-only Users folder instead.

Another important invisible folder at the Startup Disk's root is Volumes. In keeping with traditional BSD storage subsystem arrangements, Volumes contains all the UNIX mount points for all the mounted volumes on your Mac.

The details of the system mount points and technology are quite complex and beyond the scope of this article.

In modern versions of macOS, Finder windows now also display a small Eject arrow icon next to each mounted volume in the Volumes folder. Pressing the Eject icon ejects the volume next to it.

You can also view each volume's creation date and last modification date in the Volumes window.

Making Files and Folders Invisible Normally

When hidden files are turned off in the Finder, you can make any file or folder invisible by prepending its name with a period. This hides the item, and you won't be able to access it again until you turn invisible files back on or access it via the Terminal.

For example, storage volumes on your Mac store their custom Finder icons, if any, in a file at the root of the volume named .VolumeIcon.icns. The Finder reads this file, if present, when it mounts the volume and uses the icons it finds in it as the volume's desktop icon.

If you delete VolumeIcon.icns, the Finder uses a generic system icon for each volume. When invisible files are off, you don't see the VolumeIcon.icns file, but it is there nonetheless. .dmg disk images use a similar scheme for their mounted volumes.

Home Folder, Preferences, and Application Support

When you turn on invisible files in the Finder, you'll also notice a slew of invisible files and folders in your home folder. Third-party tools may store settings in invisible files or folders here, but macOS has a few of its own system configuration files in the user's home folder as well:

- .cups (UNIX printing)

- .ssh (SSH public and private keys)

- .zsh_sessions (zsh shell session records)

- .bash_profile

- .bash_rc

- .profile (login configuration scripts)

- .inputrc.sh (more Terminal session info)

- .zlogin

- .zsh_history, and .zshrc (more login scripts).

When your Mac starts and you log in, or when you log out and log back in, the system runs whatever is stored in bash_profile, .bash_rc, .profile, .inputrc.sh, .zlogin, and .zshrc.

Preferences are stored in 3 places in the macOS filesystem:

- /System/Library/Preferences

- /Library Preferences

- ~/Library/Preferences

In UNIX, the "~" character means the user's home folder.

Most of the preferences files are visible normally, but some are invisible and can only be viewed in the Finder by turning invisible files on. The same goes for Application Support folders located at /Library/Application Support and ~/Library/Application Support. Most 3rd party developers and Apple store additional files needed by apps in these 2 locations.

Occasionally while viewing your System, Library, or home folder in the Finder with invisible files on, you will see some folders with a small badge on the lower right corner - these are system-restricted folders and should not be tampered with:

If you try to double-click one of these folders, the Finder will throw an alert saying you don't have permission to open it.

Don't change the permissions on these folders to view their contents unless you know exactly what you're doing. Setting incorrect permissions on system-restricted folders can render your Mac unbootable, and can prevent the Finder from operating correctly.

You can view and change each folder's permissions in its Finder Get Info window or in Terminal, but be extremely careful. UNIX file permissions are fickle, and it only takes one mistake to prevent your Mac from working correctly.

UNIX is a very powerful operating system, and we've barely scratched the surface. By using invisible files and folders in the Finder, you can do things on your Mac you can't do otherwise.

For the more-technically-minded, the definitive book on FreeBSD is The Design and Implementation of the FreeBSD 4.4 Operating System by McKusik, et. al, but be warned: it's an extremely technical postgrad-level textbook. You can also read it online at the FreeBSD website.

One last small historical tip: if you want to see what the original NeXTStep OS was like, you can run it today in Oracle's VirtualBox or other virtualization app. AdaFruit has a cool little guide for doing so.