Just three weeks after Bluebox Security first announced the discovery of a key flaw in Google's Android with the potential to turn devices into a "zombie botnet," Symantec has reported finding rogue apps that take advantage of the vulnerability.

Source: Symantec spots new signed malware that Android can't

At the beginning of July, Bluebox went public with news of the flaw, which affected virtually every Android device in use.

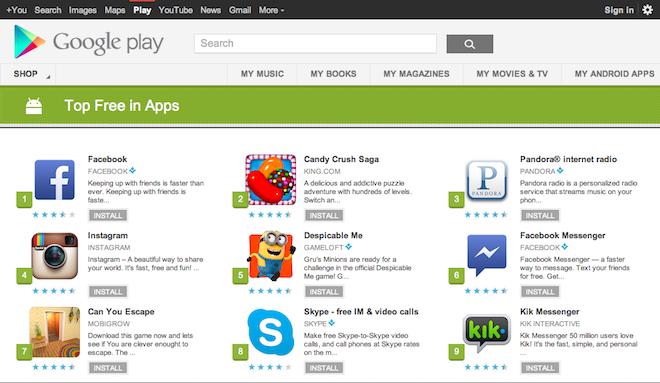

Google "declined to comment on the matter," but quickly acted to block distribution of apps seeking to exploit the issue in its own Google Play market. However, one of the primary key features of Android is the "openness" to allow users to install software from other stores.

That freedom has now morphed into a liability. While researchers quickly released "test tube" apps demonstrating how the vulnerability can be exploited, Symantec has now identified the first malware in the wild that's seeking to take advantage of the flaw, and Google's extreme difficulty in patching millions of vulnerable devices.

There's a role in Post-PC devices for Symantec after all

In a new report, Symantec stated, "we expected the vulnerability to be leveraged quickly due to ease of exploitation, and it has.""They can freely hijack legitimate applications and even an astute person could not tell the application had been repackaged with malicious code." - Symantec

The company has been scanning Android apps from "hundreds of marketplaces" using its Norton Mobile Insight tool, and initially discovered two on Tuesday.

Both (show above) were "legitimate applications distributed on Android marketplaces in China to help find and make doctor appointments."

The next day, Symantec identified another four contaminated apps, "infected by the same attacker and being distributed on third-party app sites." The exploited apps included "a popular news app, an arcade game, a card game, and a betting and lottery app," all targeting Chinese users.

The discovered malware apps are secretly modified versions of legitimate apps that most Android devices can't detect as being contaminated, thanks to longstanding flaws in Android's security system that all the eyes of the open source community failed to detect.

Weaponized for malware monetization, facilitated by flaws

Symantec earlier explained that "Injecting malicious code into legitimate apps has been a common tactic by malicious app creators for some time."

However, "they previously needed to change both the application and publisher name and also sign any Trojanized app with their own digital signature."

These modifications would render the contaminated apps easy to spot, thanks to app signing. "Someone who examined the app details could instantly realize the application was not created by the legitimate publisher," the security firm explained.

With the newly discovered Android flaw, "attackers no longer need to change these digital signature details," meaning that "they can freely hijack legitimate applications and even an astute person could not tell the application had been repackaged with malicious code."

While iOS apps can also be hacked, Apple's app signing security works to identify and block contaminated apps from working. Apple's App Store also serves as the only source for third party software outside of custom development that requires organizations to distribute their own security credentials to sign the secure encryption of such apps.

Android malware authors party like its 1999

Android apps routinely demand vast, unnecessary and inappropriate permissions to a wide range of capabilities prior to installation, in a process most users click through without examination.

The malware in the wild that Symantec has discovered has modified both apps with code "to allow them to remotely control devices, steal sensitive data such as IMEI and phone numbers, send premium SMS messages, and disable a few Chinese mobile security software applications by using root commands, if available."

The firm subsequently discovered the the malware payload, dubbed "Android.Skullkey," is also designed to send a spam text message to all phone numbers in the device's contacts, directing them to a malware website URL in a customized message that addresses the recipient by name.

Apple's iOS 6 does not allow apps to access contacts or message users without the permission of the user, but Android apps routinely demand vast, unnecessary and inappropriate permissions to a wide range of capabilities prior to installation, in a process most users click through without examination.

Android is the platform of wide open marketing research

Examples of such broad and unnecessary permissions demands start at the top: Facebook for Android, the platform's most popular app, demands access to a broad range of permissions before installation, including the ability to observe phone numbers in contacts and on calls in progress.

Earlier this month, the popular app was caught harvesting users' entire phone books for upload into the social network's vast graph, without notice, and subsequently "sharing" information with other users "having some connection to them" on the site.

Samsung, the largest Android licensee, also launched a "free" Jay Z app this month promoting its flagship "SAFE" Galaxy S4 and Note 2 phones, but with conditions that demanded access to users' precise GPS location, access to users' contacts and or social network accounts, and stats on what apps they used and what phone numbers they were calling.

Facebook and Samsung are both simply using Android the way Google intends for its platform to work. Earlier this year, after it was reported that Google Play was sending third party developers that name, physical address and email of anyone buying their apps, with "no indication that this information is actually being transferred."

Google's response was to take offense at journalists' characterization of the matter as a "flaw" and lean on publishers to remove any unflattering description of the practice from their headlines, stories, and SEO on the subject so that users simply wouldn't be aware of the issue and unable to search for information about it.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

-m.jpg)

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

Andrew O'Hara

Andrew O'Hara

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Mike Wuerthele

Mike Wuerthele

Bon Adamson

Bon Adamson

-m.jpg)

124 Comments

Both (show above) were "legitimate applications distributed on Android marketplaces in China to help find and make doctor appointments."

The next day, Symantec identified another four contaminated apps, "infected by the same attacker and being distributed on third-party app sites." The exploited apps included "a popular news app, an arcade game, a card game, and a betting and lottery app," all targeting Chinese users.

In other words these applications are being distributed on third-party app stores in China. This is akin to crying wolf about malware being distributed via Cydia. So stick to Google Play and you will be fine then.

So two chinese apps?

Not in the google play or amazon store.

Reminds me of this vid.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NO04VXBIS0M

Yay open! Oh. Wait.

DED seems quite desperate to engineer this into a big issue and stir up a panic.

So two chinese apps?

Not in the google play or amazon store.

Reminds me of this vid.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NO04VXBIS0M

They don't care. They don't realize that if you keep you never change your standard security features that this can't happen. That you have to go in the security setting and bypass the warning that pops up. That Google scans every app in it's app store using the same tools that Symantec does. That Google's nexus phones have already been patched. None of this matters to them. They just want to hate.