While tech pundits have long insisted that Apple and Google are growing more alike as rivals in smartphone and tablet computing, this week's WWDC should provide clear evidence that Apple is on a completely different track compared to the Android train operated by its formerly close iPhone services partner.

Apple and Google have charted very different courses over the past several years, and the results of those different trajectories are evident in the current status of iOS and Android in the areas of hardware innovation, security, privacy, and most importantly, their ability to both make money and achieve their stated objectives. Here's a comprehensive look.

Approaching the end of the first decade of iOS

2015 is now the ninth year of iPhone, a relatively short period of time that revolutionized personal computing with "Post-PC devices" that are not just mobile, but much more powerful than the previous generation of desktop personal computers in new ways.

Post-PC devices can be location aware and payment savvy, with ubiquitous mobile Internet access, advanced imaging features and motion sensors (just to name a few) exposed to app developers in a way that facilitates entirely new kinds of interaction, analysis and technical capabilities.

The resulting App Economy has radically transformed the balance of power from the few monolithic software developers of expensive, large applications in the 1990s (such as Adobe and Microsoft) to a wide variety of indie and startup firms creating radically new ways to connect socially; to share everything from photos to live video to rides and apartments; and to provide creativity and productivity tools that are specialized, evolve rapidly in response to user demands and quickly take advantage of powerful new OS platform features.Indisputably the world's greatest beneficiary of this massive shift toward mobile computing has been Apple

Indisputably the world's greatest beneficiary of this massive shift toward mobile computing has been Apple, the company that ignited the Post-PC revolution with iPhone, extended it even deeper with iPad, and is now aspiring to expand its influence with Apple Watch: a wearable new device that links into Siri, HomeKit, Health, Continuity, Passbook, Messages, Maps and iCloud in an ambitious effort to maintain Apple's lock on the role of being the central architect of new personal technology.

Why Apple won & why nobody believed it could

Apple's business model attaches its profit margins to the most valuable slice in the Post-PC ecosystem: the device itself. Mobile apps can be very valuable; data service can more than exceed the cost of hardware and mobile ads and cloud services can both add additional revenues, but — speaking with the omniscience of hindsight — Apple clearly extracted the most value from the Post-PC economy with the least competitive pressure, selling premium hardware.

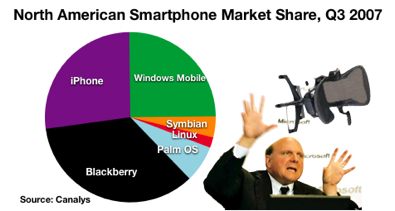

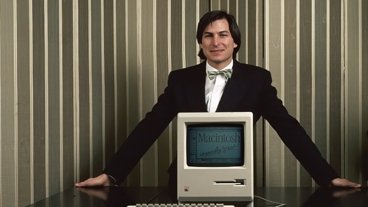

Nine years ago, virtually no one believed this could be possible, largely because the world was still impressed with Microsoft's coup d'état in appropriating and then banishing Apple's Macintosh from the mainstream market in the mid 1990s with Windows PCs.

By the time iPhone debuted in 2007, there was compelling evidence provided by six years of Apple's iPod sales that the rules of engagement had changed and Microsoft was no longer capable of routing Apple's hardware business with a flick of its software licensing pen, but those facts were ignored in favor an earlier set of data from 1995.

In part, that was because a large segment of the tech industry had been built around the feudal concept of a central software monopoly that handed out minor profit scraps to an ecosystem of beggars (Microsoft's hardware partners) in exchange for their fealty. Because Microsoft used its power to destroy anyone who didn't play along (from IBM's OS/2 to Linux), everyone else played along, licensing Windows and thus paying out most of their profits to Microsoft.

Over the first three years of iPhone, the tech media — backed up by data from Microsoft's loyal research groups — continuously propagated predictions that at some point reality would kick in and the "Law of Commodity" would necessitate that iPhone would go the way of the mid 90s Macintosh.

However, by 2010 Apple's iPhone had quite shockingly devastated not just Microsoft's Windows Mobile, but also every other mobile platform following a similar licensing model: Palm, Nokia's Symbian, various Mobile Linux distributions and Sun's JavaME (of which RIM's BlackBerry was a licensee).

Apple's Post-PC iOS had not only beat Microsoft in mobile, but everything else that looked anything like it.

Why Android was supposed to win & why everyone believed it could

Rather than recognizing that the industry's rules were being changed, the tech media and much of the rest of the industry rapidly shifted their support in 2010 to the only thing that was left: a hobbyist platform that most closely copied Apple's iOS, while at the same time promising to be free and open. Google's Android promised to be as successful as Windows in creating a communal confederation of licensees all working together; as open and flexible as Linux and as technically superior as Apple's iOS, if not more so.

Google's Android promised to be as successful as Windows in creating a communal confederation of licensees all working together; as open and flexible as Linux and as technically superior as Apple's iOS, if not more so.

Before proving any of that, Android was immediately crowned the successor of Microsoft and inherited most of Microsoft's fans, most Linux fans and even some iOS fans.

Un-Rewriting the history of Android

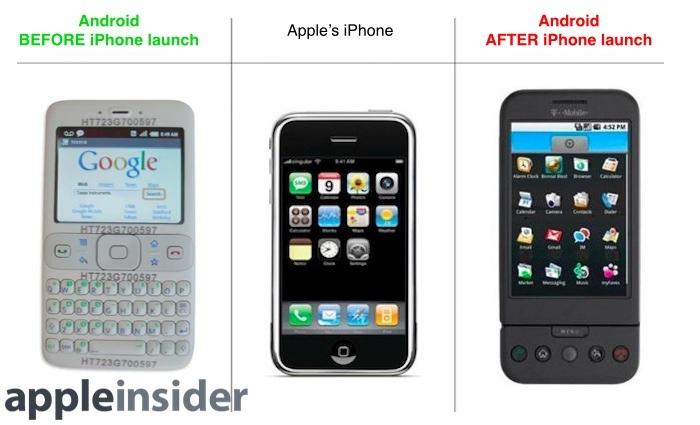

Rather than being a pioneering contemporary of Apple's iOS, it's useful to remember that Android didn't even become a significant, mainstream option until around 2010, at which point Windows Mobile, Palm, RIM and Nokia had already received their fatal blows by iOS.

That year, the industry— embarrassed by its failure to come up with anything that could actually rival Apple's iPhone— rallied around Android as its savior and launched a hype cycle orchestrated by Google, its new hardware partner Motorola and America's largest carrier Verizon Wireless (the primary competitor to the iPhone's then exclusive provider, AT&T).

Those partners collectively promised that Apple's iPhone would be savagely beaten back and relegated into a niche obscurity the same way that Microsoft and its Windows PC partners had mugged the Macintosh back in 1995.

That's a far cry from what Google is promising today: that it expects Android will continue to provide cheap phones in developing countries while Apple makes all the money creating the new technology that Android will eventually copy, poorly, without really making Google much money at all.

Back in 2010, the tech media (and the market research firms feeding it) were already exhausted and embarrassed by their own failure to anoint an iPhone killer over the previous three years as Apple's larger and far more established and higher capitalized competitors turned out one dud after another, from Symbian and Windows Mobile offerings by Samsung and Sony to the BlackBerry Storm and Palm Pre.

According to today's historical revisionists, Android was a real competitor to Apple from the very beginning, even though it actually remained a hobbyist curiosity until the mobile industry ran out of iPhone assassins and had to seize upon whatever was left after Symbian, Windows Mobile, WebOS and BlackBerry OS failed to display any lethal moves of their own.

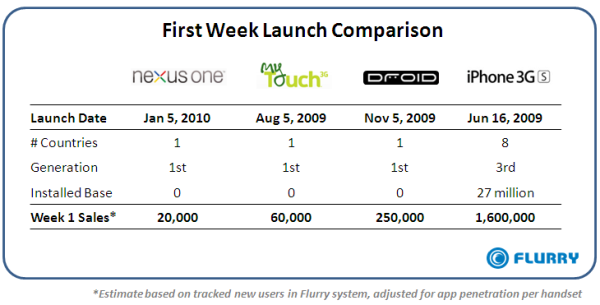

Wikipedia, for example, suggests that Android originated in 2003, because an unrelated project of the same name was experimenting with digital camera software. The first Android phone didn't actually appear until the second year of iPhone (largely because it took Google and its partner HTC that long to figure out how to get from the simple JavaME-button phone Android had been working on to a direct copy of the far more sophisticated design of Apple iPhone). Google didn't launch its own plans to "Windows 95" the iPhone until 2010's Nexus One.

Apple & Google's two very different visions for mobile devices

So really, it was three years into the iPhone's history that Google began claiming Android would quickly take the place of iOS, not just as free software competing with Apple's actual product, but in the form of Google's own new Nexus vision for an easy to buy, more flexible and "free" (as in speech) device that could access apps from a variety of sources unconstrained by Apple's restrictive iOS Walled Garden of oppression.

Google's first Nexus One also took aim at Apple's iPhone with a combination of new hardware (including a more advanced mobile chip from Qualcomm, a higher megapixel camera, a PenTile AMOLED screen claiming a higher resolution— albeit with poor image quality— and the illuminated trackball Google had been promoting as Android's superior alternative to iPhone's multitouch navigation) combined with the search giant's own cloud services (principally voice recognition for dictation and Google Maps with navigation).

Google claimed its Android software would be so open that anyone could modify it as needed. While Google expected Nexus One to sell, it also expected its hardware partners to build similar products to promote Android as a superior platform to iOS, benefitting from lots of industry-wide experimentation that would provide Google with a mobile ad platform unconstrained by Apple's rules and restrictions designed to protect users' privacy.

Overall, Google's strategies for Nexus and Android were promised to result in a faster pace of innovation than Apple could maintain, all at lower prices, again modeled upon the idea of Windows 95 facilitating PCs that were cheaper and faster than Apple's Macs had been in the mid 1990s, with some Open Source ideology thrown in to boot.

Apple keeps doing what it had been

Apple, on the other hand, maintained a strategy of a tightly curated app ecosystem for iOS, enabling the company to rapidly iterate new iOS features and architectural changes that could be quickly deployed across the installed base at regular intervals. This, Apple predicted, paired with iterative but constrained new generations of iPhone hardware, would result in a superior product experience for users.

Rather than modeling its mobile vision upon Macs of the 1990s, Apple was iterating a strategy modeled upon what it had been achieving with Macs and iPods more recently in the 2000s. Apple had been releasing nearly annual updates for Mac OS X, making it incrementally easier for developers to build software for its platform. At the same time, Apple had been rapidly introducing new generations of iPod devices, establishing operational and design savvy in hardware.

Apple had also been building a media and software ecosystem for iPods (and Macs) within iTunes, experimenting with third party software distribution in the form of iPod Games that would pave the way for mobile apps that were easy to buy and so simple to manage, update and monetize that a high volume market could be established on the back of impulse sales of low cost titles. Previously, Palm, RIM, Symbian, Java, BREW, Windows Mobile and other mobile platforms had all failed to create sustainable, high quality mobile software markets.

One other significant difference between Apple's carefully considered iOS strategy and Google's whimsically chaotic brainstorm-fantasy for Android was that Apple intended to make most of its revenues the same way it had been for the past three decades: principally via sales of premium hardware.

Google, on the other hand, had been making virtually all of its revenues from ad search placement for the past ten years. That clearly influenced the company's decision to release Nexus hardware at near loss leader prices, a practice the company continued over the next four years. It also encouraged its Android partners to compete with iPhone primarily on price, exactly as Windows PC makers had done.

While Apple's diehard fans frequently hoped the company could remain viable selling iPhones, virtually everyone in the tech media (even many of those who generally tilted toward Apple's approach) agreed that there would be no stopping Google's alliance of vendors making cheaper, faster and more open Android devices powered by Google's own advanced services and subsidized by Google's hegemony in online ads.

By the end of Android's first year of uncontested hype in 2010, however, it was clear that everything Google and its Android partners and fans had been promising as indisputable and unstoppable were actually quite easy to dispute and increasingly appeared to, in fact, be vulnerable to a series of problems associated with issues Google hadn't quite thought out in sufficient detail.

By the middle of 2010, Nexus One sales had been so poor Google discontinued it, and it mothballed its online support for the phone before the year had even ended. By that time, Verizon was ready to begin selling Apple's iOS devices, because Android hadn't attracted the same high quality demographic of subscribers that iPhones had for AT&T. Android's giddy cycle of hype fell apart within a year.

Google's Android kills iOS competitors

Android's primary achievement was something nobody predicted. While research groups like IDC were busy producing fact-guesses that assumed Windows Mobile would sputter back to life and assassinate Apple's iPhone to the delight of the very vendor who desperately needed such good news to be written and republished by the tech media without criticism, something else happened instead: Android sucked up all the little available oxygen outside of iOS.

While Apple's iPhone had critically wounded every mobile platform in existence at its arrival, the subsequent widespread adoption of Android by the vendors who had failed to compete with Apple while using Symbian, Windows Mobile, Java and Linux meant that there would be few scraps available to any Android alternatives, including Nokia's new open-source Symbian, Microsoft's efforts to reanimate Windows Phone, or the various Linux distributions in gestation at Nokia, Intel and later Samsung.

Android's success in suppressing any competitive alternatives outside of Apple's iOS threatened to cohesively align the entire industry against Apple, following (as virtually everyone had predicted) the history of Microsoft Windows. However, a variety of things had changed between 1995 and 2010 that altered how things would play out.

Why 2010 wasn't like 1995

Back in 1995, Apple had been desperately trying to emulate the Windows PC world, simplifying and cheapening Macs to work more like lower end PCs while embracing the concept of "cloner" hardware licensees. Apple had also attempted to sell new versions of its Mac OS software just like Microsoft had been with Windows. Rather than copying Microsoft's success, this all contributed toward Apple's growing irrelevance and an abandonment of what had previously made Apple a superior option at the premium end of the market.

By 2010, Apple didn't have any of those problems, largely because Steve Jobs had reversed the course of the company from following pundit wisdom to instead charting out a carefully considered executive strategy. Rather than stripping Macs of expensive features, the new Apple had been pioneering the implementation of market leading industrial design while aggressively introducing new technologies, resulting in premium products that could demand a premium price.

Apple also began leading proprietary operating system design, and shifted from giving away its Mac software to licensee-competitors to instead essentially gifting it to its end users who were actual paying customers. With the introduction of iOS, Apple increasingly designed every facet of its software to benefit the users who were paying a premium for its hardware. That meant securing their privacy and working to close security vulnerabilities rather than aspiring to permissively open everything up to "see what happens" as Google would with Android.

Additionally, Apple began applying its operational prowess to acquire components and manufacturing capacity on a vast scale— subsidized by the company's higher profit margins— which enabled it sell higher quality products at competitive prices. When Apple introduced iPad in 2010, even companies that were larger, better capitalized and more experienced at building and designing tablet devices struggled to match it.

Samsung, Motorola, HP and other Android partners had to introduce thicker, slower devices with smaller displays just to match Apple's price. Further, the low cost hardware vision of Google's Android promoted the creation of inferior, low end devices that established the platform as a third rate option for buyers on a budget.

Google's Android begins to fail in its efforts to win at being cheap

The ceaseless promotion of cheap hardware by the majority of the tech media initially resulted in some defections from iOS to Android. However, an earlier consumer trend toward buying premium Macs and iPods in favor of cheap PCs and basic MP3 players also began taking hold among smartphone and tablet buyers.

While industry research groups like Strategy Analytics relentlessly advertised Apple's plummeting "market share" of total devices, a more accurate reality was becoming evident in Apple's quarterly earnings: despite the faster volume growth of low margin commodity products, Apple was making far more money than the rest of the industry by focusing on the valuable segment of the market, the same way that most of the money in cars, clothing, food and other consumer markets occurs in higher quality tiers, not at the high volume, low end of the market.

While this was evident even before the iPhone appeared, Google and its partners continued to double down on cheapness, with Google Nexus products reaching impressive lows in retail pricing while Samsung initiated an internal strategy of winning among "carrier friendly, good enough" phones in a bid to emulate HP's success in selling high volumes of PCs while making less money than Apple.

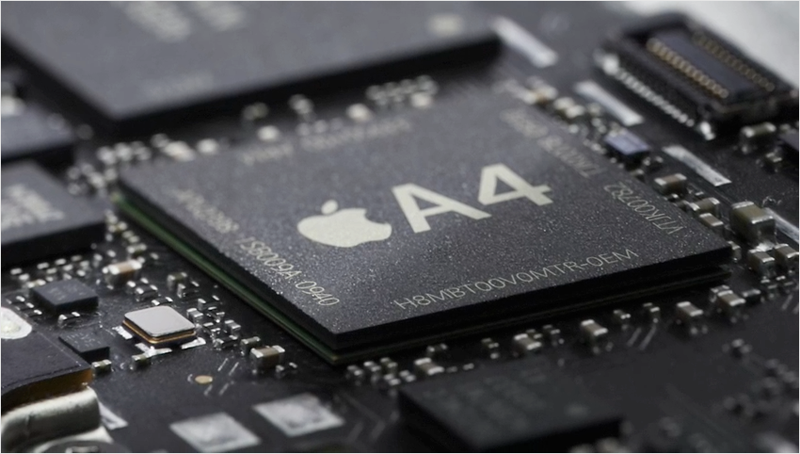

Cheapness was starving Android, even as Apple began to rapidly invest its earnings into developing superior technology. Six months after iPad was introduced, Apple leapfrogged Android in smartphones with iPhone 4, using the iPad's same proprietary A4 processor design. It also introduced not just a nominally higher resolution display, but one that was demonstrably superior and easier for developers to take advantage of in way that enhanced the iOS platform.

iPhone 4 also introduced Apple's first foray into providing a very good camera, a strategy that has developed into the primary feature Apple has been using to market today's iPhone 6 (note that's its ability to take great photos, not its larger screen size).

Google's Android fails at hardware innovation

Google experimented with Android's LED trackball for two years and then abandoned it (and other buttons) to more closely copy Apple's hardware designs. That's a move Nexus— and Google's Android partners— have also replicated in the areas of SDCard support, removable batteries and other tactics once advertised as Android's compelling, differentiating features. At the same time, Apple spent years developing its own Maps and Siri in a bid to match Google's services bundled with Nexus.

The media gave a pass to Google's Android hardware failures, but assailed Apple's first attempts to take on Google's cloud services, despite the reality that Google's original hardware experiments have routinely ended up as abandoned failures while Apple's initially flawed services have matured into very competitive offerings that have indisputably helped to sell iOS devices at the expense of Google.

For years Android's supporters— including many so-called journalists— have been insisting that up is down and black is white, then suddenly growing silent when all evidence shows that they were wrong.

In the ninth year of iPhone, Apple's latest iPhone 6 has maintained a strong lead with its advanced A8 processor, superior camera and excellent screen quality— albeit at a lower pixel resolution that improves its graphics performance— eviscerating the notion that Android would facilitate the world's hardware vendors to innovate faster than Apple could.

The only Android licensee even approaching Apple's success is Samsung, a company that strives to copy Apple's industrial designs, its feature implementations and its initiatives ranging from Passbook to Touch ID to Apple Pay. Despite all that, Samsung is making a fraction of Apple's earnings despite churning out more devices, most of which are lower end products with poor user satisfaction ratings.

Samsung was already achieving moderately successful mediocracy before Android appeared in the market. And even worse for Android: Samsung is aggressively working to replace Google's Android with its own Tizen platform.

Google's Android fails at platform competency

Being bad at hardware hasn't been the only problem affecting Google's platform. Google was also clearly inexperienced at Apple's second core competency: maintaining a software development platform.

While initially promoting "openness" in the availability of apps from any source and in the open sourcing of the underlying software itself, Google has backpedaled upon both concepts.

In 2011, Google closed access to Android 3.0 source to prevent the very experimentation it claimed would make Android a superior platform.

It has also implemented most of its own client software and many of its development tools and libraries as closed source. If Google were honest about its devotion to open source, it wouldn't be copying Apple's proprietary software development in the areas that matter to the company's bottom line.

Even more problematic than Android's infidelity to its supposed commitment to open source, however, is its backtracking on the subject of "open software markets," something the company once touted as a primary reason to pick Android.

Early on, Apple insisted that third party software on a mobile device would expose a series of serious potential problems that would need to be addressed with comprehensive security strategies to regulate what apps could do. Central to that goal of security was Apple's intention to only allow users to install signed software that had passed a stringent quality control examination. Apple's critics and proponents of Google roundly mocked and belittled Apple's efforts to erect a "Walled Garden," but a comparison of the end results of both approaches shows they were unmistakably wrong.

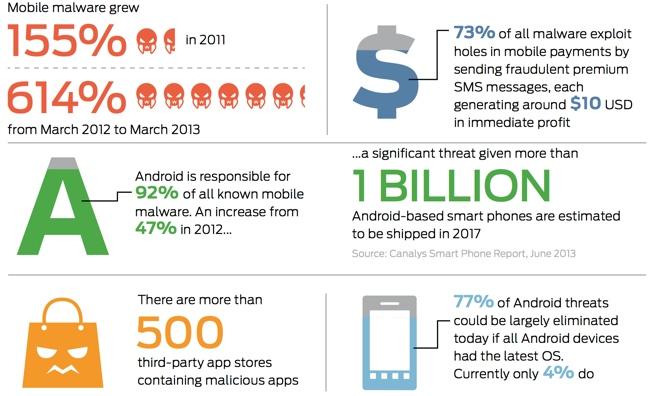

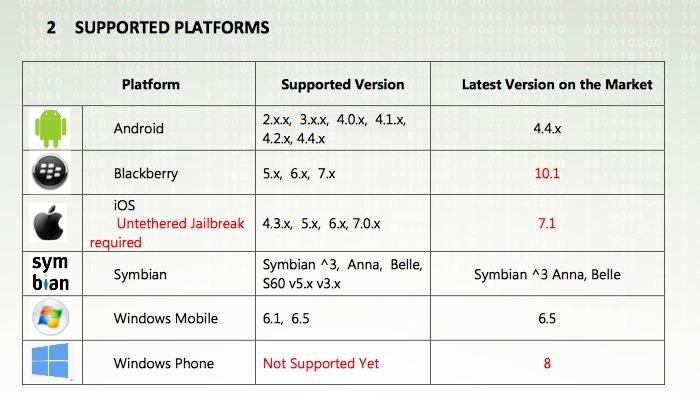

The ability to sideload apps from any source— particularly with such ease that users can easily be tricked into installing apps simply by clicking a link— has resulted in a security nightmare for Android. It has kept the platform out of serious enterprise deployments, and has caused widespread victimization of nontechnical users who have been left on the hook for SMS payment scams worldwide and has caused broad and extensive botnet infections, adware and other malware attacks ranging from annoying to disastrous.

Government agencies and university researchers began issuing warnings about Android's insecure-by-design nature almost immediately, and over the past four years of Android, a series of leaks and security reports have shown that it is incredibly easy for anyone to monitor and track the majority of the Android installed base.

Vendors openly sell law enforcement surveillance tools that are easily obtainable by anyone (even on Google Play), which are capable of listening into Android users' conversations, accessing documents on their devices, tracking their location, and taking over full control of their phones.

These aren't potential vulnerabilities; they are actively exploited flaws that are directly related to Google's rejection of Apple's security policy for iOS. These same tools regularly state that they can not be used to gain similar access on iOS devices unless they have been "jailbroken," a purposeful security system bypass that Apple has worked to block.

A recent report by NBC News warned the "93 million Americans with an Android phone" how easy it is for spies to gain virtually complete access of their devices.

Sophos security researcher James Lyne demonstrated how in just seconds he could hack into a reporter's Android phone, grabbing photos as he took them, tracking his location as he walked around Las Vegas, listening into his phone conversations and tracking his browsing history while stealing his contacts and downloading a listing of the calls he placed.

Lyne even demonstrated his ability to hack into the phone's microphone to listen into his conversations made even while not even talking on the phone.

The report quoted Google in responding to the report as saying that "security is improving each month," while offering the advice that users "should only download apps from Google Play," the same line of reasoning Google has mocked for years as it likened Apple's App Store policies to the brutal regime in control of North Korea.

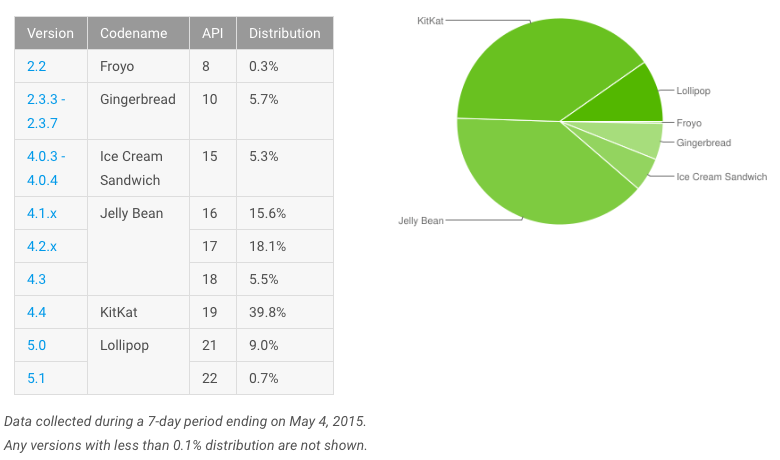

Google also recommended that Android users should keep their apps and operating system "up to date," even though Google itself routinely fails to make updates available to its users on a timely basis. The company has abandoned support for its own Android Browser, exposing millions of users— the majority of its installed base— to a wide range of open vulnerabilities because continuing to support those low value users would be too much work for the company.

The latest major version of Android 5, released last fall alongside Apple's iOS 8, is still not even available for most Android phones, and less than ten percent of the active users on Google Play have it installed, according to the company itself. Apple says that 82 percent of active iOS users have installed iOS 8.

That's a situation that simply isn't getting better across several years of Google's management of Android as a platform. Real-world security on Android is getting worse because spies are getting better at exploits faster than Google is getting less complacent about Android's security issues.

Google's Android fails at privacy

It's not just platform security that Google is poor at managing. Because the company makes most of its revenues from selling ad placement rather than selling software (as Microsoft did with Windows) or hardware (as Apple always has with Macs, iPods, iPhones and iPads), Google is financially motivated to design its products to collect and share users' data, behaviors, preferences and activities.

Apple has recently drawn increasing attention to its protection of user privacy. While Apple aggregates users' App Store purchases in a way that allows iAd advertisers to target specific demographics of iOS users (enabling developers to market games to users who actually play games, for example), Google collects and monetizes data on a completely different level.

Google recently raised eyebrows by claiming perpetual rights to use any photos uploaded to Google Photos in its own advertising, royalty free. And while it failed to copy Facebook's success in its own Google+ initiative, its efforts in that regard show that it makes poor decisions when unilaterally setting aside users' expectations of privacy to serve its own whims, associating a user's accounts and advertising personal information in ways that user wouldn't expect.

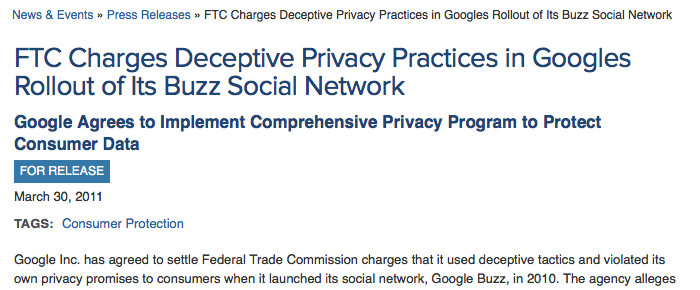

When Google attempted to copy Twitter with Google Buzz, it sucked up users' contacts and automatically shared them publicly. That's not a privacy policy most people would expect to be the default, but for Google, sharing other people's data is done automatically without really thinking about the consequences.

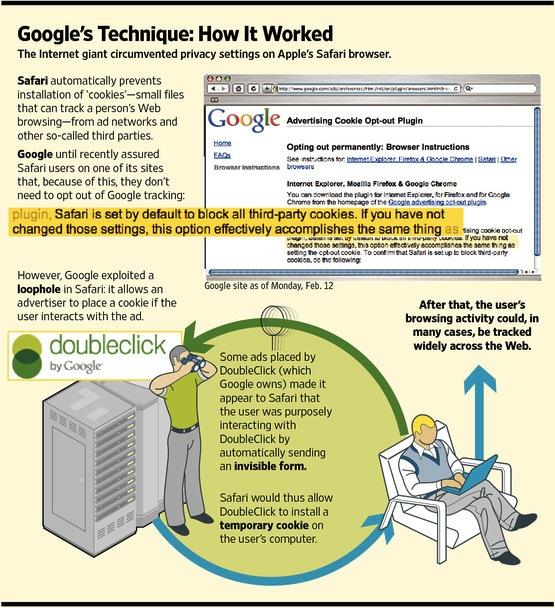

Sometimes Google does think carefully about privacy. When it found that Apple's Safari browser was restraining it from grabbing more liberal access to users' web behaviors (as allowed by its own Chrome browser), it developed sophisticated tricks to bypass user preferences and track and monetize users' behaviors on the web anyway, then misrepresented what it was doing, at least until it was caught doing it. Google not only has zero respect for its users' privacy, it also has zero respect for government regulators

And Google did this less than a year after it supposedly "agreed to settle Federal Trade Commission charges that it used deceptive tactics and violated its own privacy promises to consumers when it launched its social network, Google Buzz," agreeing to a settlement that supposedly "bars the company from future privacy misrepresentations, requires it to implement a comprehensive privacy program, and calls for regular, independent privacy audits for the next 20 years."

Google not only has zero respect for its users' privacy, it also has zero respect for government regulators seeking to curtail its privacy-violating behaviors and its misrepresentations of those violations, despite a series of firm slaps touching its wrists.

Google's core competency is collecting and sharing other people's data, and it makes its money by doing this next to its display advertising. This makes sense for pages of information that are published on the web explicitly to be seen by everyone else. But it makes no sense to apply those same permissive web policies when Google acts as a cloud services company storing users' private documents, photos, contacts, calendar events and other data.Google has done such an atrocious job of securing Android that it really calls into question whether it can be trusted with any data that isn't explicitly public information intended for unrestricted broadcast

Google has done such an atrocious job of securing Android that it really calls into question whether it can be trusted with any data that isn't explicitly public information intended for unrestricted broadcast.

That applies not just to user data like contacts, but also user behaviors: the websites you load, the apps you use, the places you take your Android devices, where your Android Auto equipped car is parked, and so on.

While Apple's Tim Cook has continued to voice the same user privacy concerns Jobs had before him, Google's executives, most notoriously Eric Schmidt, have repeatedly articulated contempt for the notion that anyone has any right to privacy online, while at the same time flatly denying that there is any difference between Google and Apple in terms of user privacy or security. Both things can't be true.

Many of the same media sources that have perpetuated Google's false promises about Android's openness, its ability to innovate and its security have now taken the search giant's side in recommending that users just stop worrying about their own online privacy, because many people already don't care.

Individuals who should be tastemakers in technology have a responsibility to inform their readers. Instead, a broad range of columnists have turned their pulpits into soapboxes advising a full surrendering of all privacy to Google and other ad-centric companies whose primary customer is not the user, but rather the advertiser, because of the shiny baubles being dangled in front of them, for free!

A variety of Google's apologists have also insisted that Apple and Google are really the same in privacy because Apple operates its own iAd advertising service, too.

iAd does enable ad-supported apps to display ads targeted at buckets of users based on the purchase history of the user. However, Apple's iAd does not build profiles on users the way Google and Facebook do.

Apple doesn't use data gleaned from messages or mail to build up a dossier on the user's apparent interests; it doesn't link together users by scanning contact records or Likes to create a "user graph" that predicts what an individual's interests are based on who they know and where they live; Apple doesn't scan users' photos to identify their pets and friends and products they use; and Apple specifically does not harvest user data from sources including Siri and Maps requests, Health, HomeKit configurations or iPhone call history, iMessages, Contacts, Calendar or other private data.

That's a vast difference from companies whose primary business model is based upon gleaning marketing data from any user data they can get ahold of, a policy that directly supports the "free" services they offer to induce users to share their information with them.

Users may trust today's Facebook and Google, but data you allow them to compile and publish in perpetuity with an explicitly lacking expectation of privacy becomes a serious issue when those companies leak or otherwise mishandle that data, inadvertently sharing it in public as Google has, delivering it to other companies and agencies in a way that can be used against you— maliciously or incompetently— in ways similar to the history of identity thieves and credit reporting bureaus who collect false data that's subsequently difficult or impossible to correct, with material consequences.

By making its money in a straightforward, easy to understand transaction that trades your cash for a supported, secured, privacy-protected device, Apple has erased the nagging questions of how it might mishandle your data, because it simply doesn't collect that data in first place.

If Google were able to sell hardware at a similar profit, it could also abandon its data skimming business model and rapidly begin making tons more money for its shareholders, just as Apple consistently has.

Unfortunately for Google, it has struggled to gain a similar competency in selling hardware, despite years of efforts in trying to develop and market Nexus devices in repeated attempts to codevelop products with partners including HTC and Samsung; in years of failed efforts to turn Motorola Mobility around and begin developing a pipeline of desirable, profitable products; and in its most recent efforts to turn Nest around into a viable hardware business, rather than a free range Kickstarter-style think-tank that so far has only created a defective-by-design smoke detector and a very expensive thermostat.

Google IO vs Apple's WWDC

This year, Google's weak IO conference attempted to refashion Android as being even closer to Apple's iOS, throwing away more of the quirky, inscrutable engineer-centric designs that differentiated Android as a platform and instead copying everything Apple introduced last year.

While Samsung has proven that stealing designs and initiatives from Apple is the best way to be second best, there's little evidence that Google can ever massage Android into a product that attracts the same demographic that iPhones, iPads and other Apple devices attract. Further, trying to do with with a privacy-averse, advertising-first business model appears to not be a very successful path.

Last year, WWDC introduced a variety of very novel concepts that thoughtfully put existing technologies to work to make better products, a stronger platform for developers and an even stickier ecosystem for users.

When Apple introduced Continuity last year, it was readily apparent how it would immediately improve the use of Macs and iOS devices together. It wasn't until Apple Watch appeared, however, that even more of its additional potential was apparent.

In a similar fashion, there are lots of deeper, lower level technologies being introduced each year at WWDC that go on to provide a foundation for new capabilities, features and even enable new product categories. Apple is currently leading a relentless race in introducing new user technologies, now in the car, gym, home, hospitals and in research.

Apple's iOS continues to deliver— above and well beyond— the initial promises with which it was introduced on the iPhone nine years ago, as an "iPod, phone, and a breakthrough internet device." In stark contrast, Google's Android— which promised to differentiate itself as free, open and permissively liberating— simply is not.

This week, WWDC promises to provide further proof that Apple— not Android— will be driving innovation into the future. Based on Apple's past performance— during which it had larger, more established competitors— provides some clarifying insight into how the future will play out, now that Apple is armored with massive billions in capital and is a far larger company than it was in 2007, allowing it to make even more aggressive investments in parts, people and production capabilities.

Market success as measured by money

Over the past nine years, Apple's leadership and competence with iOS has resulted in the company growing in value by more than 960 percent since the beginning of 2007. Apple now earns more money that any other tech company by a wide margin.

Over that same period, one-time PC leader Microsoft has grown by just under 56 percent, while Adobe has grown just over 93 percent (despite both companies making significant efforts to remain on top of apps as the market shifted toward mobile).

HP— the world's leading PC hardware vendor when iPhone appeared— has seen its valuation drop by nearly 20 percent over the same period as consumers and businesses increasingly shifted toward mobile computing.

At the same time, once-leading mobile device vendors Nokia and Blackberry have collapsed in valuation since iPhone debuted, with Nokia's stock down by nearly 65 percent and the former RIM imploding to a valuation almost 93 percent lower than it was before iPhone.

In fact, today's Apple— even at a market capitalization that most analysts believe to be undervalued by investors— is currently being appraised by the market as being worth more as an enterprise than Microsoft, Adobe, HP, Nokia and BlackBerry combined. Those companies in total are actually worth less than 60 percent of Apple's current $731 billion market cap.

The only way to deny that Apple hasn't absolutely trounced the PC industry while simultaneously crushing former mobile device heavyweights over the past nine years of iOS is to contrive a new definition of success where corporate efforts aren't graded by the real world results they achieve, but rather awarded by the amount of effort they claim to expend and the amount of hot air they expel in the direction of the tech industry's windmills of public relations-regurgitating content generators sometimes depicted as industry journalists.

Apple's disputed success

The job of real journalists is to record and report what is actually happening for the benefit of an informed society. However, Apple's industrial success has so thoroughly threatened the status quo that an army of naysayers have been enlisted and propped up by the company's rivals to spew fiction, fear and contrived statistics that portray up as really being down.

This non-stop propaganda suggests Apple is positioned at a dire crossroads of irrelevance and doom, while pretending that everything Apple has achieved has only been in conjunction with its competitors, even if those competitors haven't ever come close to matching Apple's financial results or technical achievements.

Take for example Google's Android. It is virtually impossible for Apple's iOS to be mentioned by the media without "and Android" being tacked onto the end, as if the two were Gemini twins locked in a symbiotic partnership sharing the same blood and making all the same moves. Nearly every media report will further add that Android is the more popular twin, with more devices worldwide shipping with some form of Android code in them.

This is a curious claim, given that over the same nine years, Google's market cap has only increased by 140 percent. Clearly, Google did not benefit from the rise of mobile to an extent comparable to Apple.

And actually, much of Google's increase in valuation occured in 2013, and Google's stock is currently lower than it was at the end of 2013.

That, coincidently, was also the year that the tech firmament proclaimed that Samsung and Google had trounced Apple and that iPads were imploding and that Apple itself was devoid of any capacity for innovation, despite the very clear reality that Samsung and Google were fighting while earning much less than Apple (particularly in tablets), and that innovation is rooted in hard work and research, not in dubiously splashy and hollow claims issued at circus-like events designed to dazzle and exploit the credulity of the tech media.

Please, dear journalists, stop lying. Stop telling people privacy doesn't matter, and that platform security is just a random result of unpredictable cosmic forces nobody can predict, and that technical competency is something to despise and ridicule, and that failure should be celebrated because it means Google was trying. We know better, and it just makes you look non-credible.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

-xl-m.jpg)

-m.jpg)

Wesley Hilliard

Wesley Hilliard

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Mike Wuerthele

Mike Wuerthele

84 Comments

We really need a clapping emoji.

And Samsung did the same in the Android market; for those reasons I want to see Google and Samsung continue to decline into irrelevance; that's better than bankruptcy.

As for the privacy claims many spout, about how people don't care, I have this: http://techcrunch.com/2015/06/06/the-online-privacy-lie-is-unraveling/

People do care. They just need someone to follow.

It’s all true, every word of it. This is not an editorial. This is a history lesson. I vividly remember the drumbeat that iOS and Apple would be dead and buried within months, not years. And before that the iPod would be crushed by cheaper music players. And before that the Bondi Blue iMac was a joke and would be a failure. And before that...

Great article. There seems to be an obsession with Apple in the news, they have to cover Apple, cause that's where the money is and that's what people click on, so they just write negative stuff to disguise their obsession. I'm excited for WWDC 15 for a number of reasons, most of them are because of technologies already in place. I think the Apple Watch, homekit, and healthkit will begin to shine. I'm very excited for Apple Watch, I think this will be a defining event for that product. It will show the direction Apple is going to take it.

Reads like a piece from Chinadaily.

Excellent chronology of the facts, but I was happy to read the following: "............but rather awarded by the amount of effort they claim to expend and the amount of hot air they expel in the direction of the tech industry's windmills of public relations-regurgitating content generators sometimes depicted as industry journalists." I hope to see more of this from true journalists as yourself. So often I hear 'it's a matter of preference' when in fact, it is about all this article mentions.