As expected, Apple intends to argue its First Amendment rights as part of a multi-pronged legal strategy designed to flout a court order compelling the company unlock an iPhone linked to last year's San Bernardino shootings.

Theodore Boutrous, Jr., one of two high-profile attorneys Apple hired to handle its case, said a federal judge overstepped her bounds in granting an FBI motion that would force the company to create a software workaround capable of breaking iOS encryption, reports the Los Angeles Times.

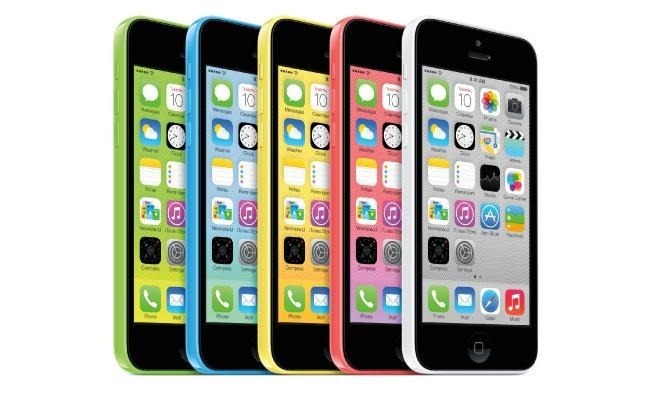

Specifically, U.S. Magistrate Judge Sheri Pym last week ordered Apple to help FBI efforts in unlocking an iPhone 5c used by San Bernardino shooting suspect Syed Rizwan Farook, a directive that entails architecting a bypass to an iOS passcode counter. Government lawyers cited the All Writs Act of 1789 as a legal foundation for its request, a statute leveraged by the FBI in at least nine other cases involving iOS devices.

While the act itself is 227 years old, lawmakers have updated the document to cover a variety of modern concerns, most recently as applied to anti-terrorism operations. In essence, All Writs is a purposely open-ended edict designed to imbue federal courts with the power to issue orders when other judicial tools are unavailable.

A 1977 Supreme Court reading of the All Writs Act is often cited by law enforcement agencies to compel cooperation, as the decision authorized an order that forced a phone company's assistance in a surveillance operation. In Apple's case, however, there is no existing technology or forensics tool that can fulfill the FBI's ask, meaning Apple would have to write such code from scratch.

"The government here is trying to use this statute from 1789 in a way that it has never been used before. They are seeking a court order to compel Apple to write new software, to compel speech," Boutrous told The Times. "It is not appropriate for the government to obtain through the courts what they couldn't get through the legislative process."

Boutrous intimated that the federal court system has already ruled in favor of treating computer code as speech. In 1999, a three-judge panel of the 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals, which covers California, ruled that source code relating to an encryption system was indeed protected under the umbrella of free speech. That opinion was later rendered moot, however, meaning there is no direct legal precedent to support Apple's arguments.

The comments expressed by Boutrous echo those of Apple CEO Tim Cook, who earlier this week called for the government to drop its demands and instead form a commission or panel of experts "to discuss the implications for law enforcement, national security, privacy and personal freedoms."

Apple is scheduled to file its response to last week's order on Friday.

Mikey Campbell

Mikey Campbell

-m.jpg)

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

Mike Wuerthele

Mike Wuerthele

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

Sponsored Content

Sponsored Content

Wesley Hilliard

Wesley Hilliard

41 Comments

The better argument is the 4th Amendment, unreasonable seizure (of property). It takes employee (highly paid employee) time to produce a workaround for each of 17000 phones, and we are not going to give you the keys to our kingdom......

If a civilian or gov't wants to find a security hole in the code and then exploit it legally, go right ahead, but to have a private company build you a backdoor option into a every device they make is just too ridiculous to imagine.

Political free speech has more protection from the courts (Bill of Rights) than other speech. I think the judge's order to Apple violates the Takings Clause (5th Amendment) by requiring Apple to provide resources for public use without just compensation. Just compensation may require not only that Apple be reimbursed for its out-of-pocket expenses in writing new software for the FBI, but also damage to its reputation and lost earnings. It seems little doubt the FBI is asking the judge to override the Takings Clause. The actions of the terrorist left the iPhone 5c in a state where Apple was able to render assistance (legally) to the FBI, but after that the owner of the iPhone -- under the FBI's direction -- changed the iPhone's password and placed it in a different state where Apple was no longer able to render assistance. Therefore, the FBI insists that Apple hack a device neither owned, nor possessed nor password-protected by a terrorist, but by the FBI. Thus, the judge's Writ empowers the FBI to commandeer Apple resources to aid in a programming problem of its own creation.