Cellebrite — the firm thought to be responsible for helping the FBI extract data from the iPhone of San Bernardino shooter Syed Rizwan Farook — is doing "lawful unlocking and evidence extraction" from Apple devices through the iPhone 6 and 6 Plus, according to the company's Forensics Research director.

"Cellebrite's CAIS now supports lawful unlocking and evidence extraction of iPhone 4S/5/5C/5S/6/6+ devices (via our in-house service only)," Shahar Tal said on Twitter. CAIS refers to the company's Advanced Investigative Services division, which offers data extraction for criminal investigations even when devices are encrypted or damaged.

The firm's website still only promises "the physical extraction of data" from the iPhone 4S, 5, and 5c. Farook's phone was a 5c.

It's not clear why Cellebrite is unable to handle the iPhone 6s or 7 — at least officially — but the limitation appears to be the processors involved, topping out at the A8 used in the iPhone 6 line. Similarly-equipped iPads are allegedly within reach.

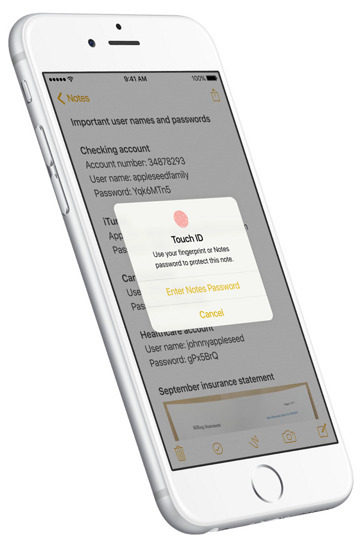

The A7 and A8 should in theory make Apple devices difficult to hack physically, since they include a Secure Enclave that stores Touch ID data. Indeed people who tried updating an iPhone 6 to iOS 9 ran into error messages if they'd had unauthorized repairs affecting the Touch ID system.

On Monday, three major news organiztions — the Associated Press, USA Today, and Vice — insisted that the U.S. government disclose basic information about the tool used to unlock Farook's iPhone, including the source company and how much it cost. The Justice Department has offered very few details, claiming anything more might result in groups developing "countermeasures" against the FBI.

The Department initially sought to persuade Apple to build a backdoor into Farook's phone, but relented when it found third-party help. Apple argued that it couldn't be compelled to write new code, and that doing so in this case would permanently weaken iOS security.

Roger Fingas

Roger Fingas

Thomas Sibilly

Thomas Sibilly

Wesley Hilliard

Wesley Hilliard

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

-xl-m.jpg)

10 Comments

It would be funny if they put "lawful" in quote in their press release, perhaps followed by a [nudge nudge, wink wink]. Almost anything can be "lawful" if you do it in the right country.

"The A8 should in theory make Apple devices difficult to hack physically, since it includes a Secure Enclave that stores Touch ID data." Just to note: Secure Enclave debuted in A7 for iPhone 5S.

Apple should try to buy this company.

So much for needing to force Apple,

to build in a back doors. ….Never ever ever. Please!

If anything, Apple needs to keep improving their security, and staying ahead of

Los Federales.

And No, ….I Use 100% Nothing of Google, Facebook, etc.

my online persona, is 100% tied to "an online persona email address". …that I never ever use.