Eight years ago today, Steve Jobs introduced iPad, positioned as a new device category between the highly-mobile iPhone and conventional Macs. Some critics were disappointed that it wasn't a Mac in tablet form; others were upset it wasn't a telephone, that it wasn't smaller, that wasn't larger— or that it effectively was a larger iPod touch. All critics have since agreed that iPad is a disastrous, disappointing problem Apple should feel bad about despite it being the most popular, most profitable, most influential new form factor in personal electronics since iPhone itself.

A Pad, born without a viable route to market

By 2003, Apple's iPod was on its way to becoming a blockbuster hit franchise. The new music player had shifted the company from being a specialized PC maker into a new force to be reckoned with in consumer electronics. Internal development subsequently began on an even more ambitious project: a lightweight tablet device oriented around Apple's new Safari web browser, internally referred to as "Safari Pad."

Work on thin, light ultra-portable network computers had been going on in labs outside of Apple for many years, but most of these were based around the idea of a server-hosted UI displayed on a highly mobile, dumb terminal connected by a fast wireless network. By the early 2000s, WiFi was solving the problem of a fast-enough network. However, the concept of tethering tablets to a remote server doing the heavy lifting hadn't taken off.

Apple's approach with Safari Pad followed a familiar strategy for the company: making the local device smart enough to work on its own, rather than being just a dumb video screen blasted with updates over the wire. However, one obvious problem for Safari Pad was that Apple's customers were already accustomed to using the rather heavyweight Mac UI, based on a precise mouse pointer and keyboard. Selling them on a feature-reduced tablet powerful enough to do some tasks but lacking the horsepower of a typical Mac was seen as a stretch, particularly at the price such a device would require.

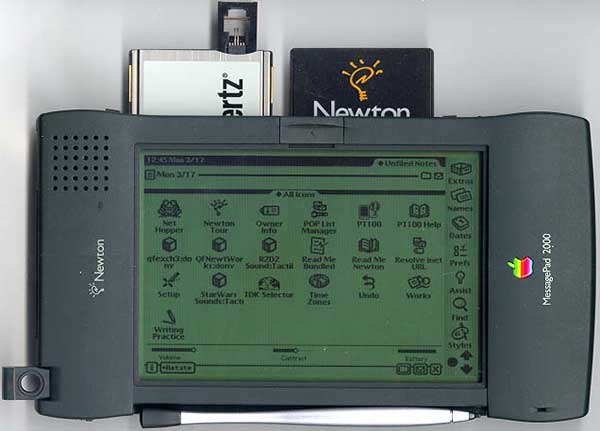

Apple's Newton Message Pad 2000 with expansion slots. | Source: Aaron Eiche

Apple's Newton Message Pad 2000 with expansion slots. | Source: Aaron EicheApple had the failure of its Newton MessagePad (which Jobs finally canceled in 1998 after four years of unimpressive sales) fresh in mind. The state of the art in developing a "smart screen" handheld tablet that attempted to sort of be a smaller desktop computer simply couldn't deliver enough valuable functionality and performance at a price attractive to the mainstream market. A simpler, cheaper PDA (such as a Palm Pilot) was good enough for many, and for everyone else it made more sense to buy a fully-capable notebook computer.

In parallel, Microsoft had been attempting to get its PC partners to sell Tablet PCs: essentially Windows notebooks either in a stylus-driven slate format without a keyboard, or a "convertible" notebook with a complex hinge that tried to coax a standard old laptop to jump through new hoops. But these had all repeatedly failed, wave after wave, as buyers saw too little new functionality at too high of a price compared to the basic bog-standard PC notebook.

Scaled down to scale up

Work on Safari Pad at Apple was instead identified as an ideal starting point for developing a more sophisticated mobile phone rather than a scaled-down notebook Mac in the shape of a tablet.

Prior to iPhone's debut in 2007, "smartphones" were barely capable of running simple Java applets, playing a limited number of MP3s, sending simple text messages and pulling up the "baby Internet" of simplified mobile web pages using WML, iMode or WAP to spoon-feed content to anemic devices.

By scaling down its macOS frameworks and core OS to run well on a newly-emerging class of ARM chips, Apple was able to launch iPhone as a huge leap in mobile performance, capable of browsing and navigating actual web pages; sending and receiving standard emails with attachments; organizing, playing and buying music and videos— and even browsing Google Maps using a new mobile interface designed by Apple to make Google's maps for the web into a flawless, multitouch experience equally impressive to its Safari, Mail and iTunes apps.

iPhone rapidly vaulted from a ballsy bet into a massive success, cloning the iPod's successful iTunes Store into a new iOS App Store where third party, powerful mobile iPhone apps could be developed for a rapidly expanding audience of enthusiastic buyers.

After creating a platform of mobile iOS users that was significantly larger than the installed base of its Mac buyers, Apple was now in the position to sell its new iOS users an expanded tablet-sized device that its conventional Mac users initially would not have seen as powerful enough to do their familiar tasks.

And sure enough, when Apple launched iPad in 2010 it was dismissed and critiqued by many Mac users as not being powerful enough, but enthusiastically adopted by people who were relatively new to iPhones and eager to use their familiar apps on an even larger canvas.

A success story expressed as a crisis

Sales of Apple's new "big iOS device" were far higher than analysts had expected. They looked at existing tablet customers, mostly a small niche of people drawn to various fragments of Microsoft's Tablet PC project, and saw very limited potential for a new tablet. They looked at existing PC and Mac users and saw audiences who expected tablets to match the features of a "full desktop OS," including things like rendering Adobe Flash content on the web and working with application documents in multiple overlapping windows.A primary reason why analysts are so frequently wrong about Apple is that they look at the company through the distorted lens of the status quo

A primary reason why analysts are so frequently wrong about Apple is that they look at the company through the distorted lens of the status quo, expressed in the generally unsuccessful (either by lack of ambition or giddy credulity) new product attempts of its rivals, or the basic commodity offerings they've been selling on a runway that leads toward lethal price erosion.

iPad was broadly seen as a failed attempt to replace the Mac, something it doesn't attempt to do, and which would be foolish for Apple to aspire to do. Apple was quite clearly familiar with the fact that it was selling far more iPhones than Macs. While it was doing everything it could to expand Mac sales, iPad offered an opportunity to sell a new type of computing device to users familiar with iPhones but not Macs.

The idea that Apple was trying to shift its Mac customers (who every few years were paying around $1000 to upgrade their device) to instead buy a tablet priced at around $500 or less is simply asinine. iPad was targeted expressly at iPhone users who wanted to expand their iOS experience.

This strategy clearly paid off. Sales of the new large iOS devices boomed and then boomed again with the introduction of iPad mini, which delivered the same "larger iOS experience" in a lower priced package. However, after reaching a peak in 2014, sales of large iOS devices with iPad branding began falling.

Apple's latest reported FQ4 unit sales of iPad have fallen by 26 percent since the Q4 peak back in 2014. The company will announce its holiday quarter sales next week, and those numbers will clearly be far below the all-time quarterly high reached in the winter of 2014: a whopping 26 million iPads sold in just three months.

The same people who opined from their soapbox blogs that iPad needed to be more like a Mac to attract buyers like themselves subsequently congratulated themselves for outlining why iPad would fail as they predicted. But they were wrong on both accounts. iPad sales went down because Apple began offering a "large iOS experience" integrated into its larger-screened iPhones starting with iPhone 6 and 6 Plus.

This wasn't a problem for Apple because iPhone buyers tend to replace their phones faster than the typical refresh cycle for iPad. Apple didn't force buyers to shift from using an iPhone and an iPad to a larger iPhone Plus; it simply offered a wider variety of options to attract as many different kinds of buyers as possible.

However, Apple didn't ever scale down its Mac lineup to make a macOS tablet, or to bring windowing or other desktop Mac legacy to iOS. The most obvious reason for Apple's one-way expansion is that the Mac users base is (relative to iOS) quite small and is only growing very slowly. There's simply very little great potential to spawn new product categories from the stalk of that user base.

The premise of iPad

The key value of iPad is that it delivers a larger canvas for familiar iOS apps (and is easy for existing iOS developers to target). It accomplishes this by focusing on what makes smaller iOS devices great: they are simple to use and aggressively manage battery and memory use to deliver extended battery life on an affordable, highly mobile device.

Layering on the complexity of the more sophisticated Mac UI— which was designed to be dependent upon a larger power supply and the assumption of a faster processor and availability of more RAM and copious storage— is how Apple would strip value from iPad, rather than being a way to improve it.

By keeping its iPad and Mac lines distinct, Apple has set clear expectations for each, and made each very good at different things. There is some overlap; writers can type on either; musicians can compose and perform songs on either; artists can paint and sketch on either and business people can present, chart and message on either.

However, the two products are aimed at very different types of uses, without a mingling of expectations that would only complicate the decision of whether high mobility or full performance is clearly more important to a specific task. Hybrids in mobile electronics are typically worse than a product designed to be optimized for a specific task, an idea conveyed by Tim Cook using the phrase "refrigerator-toasters"

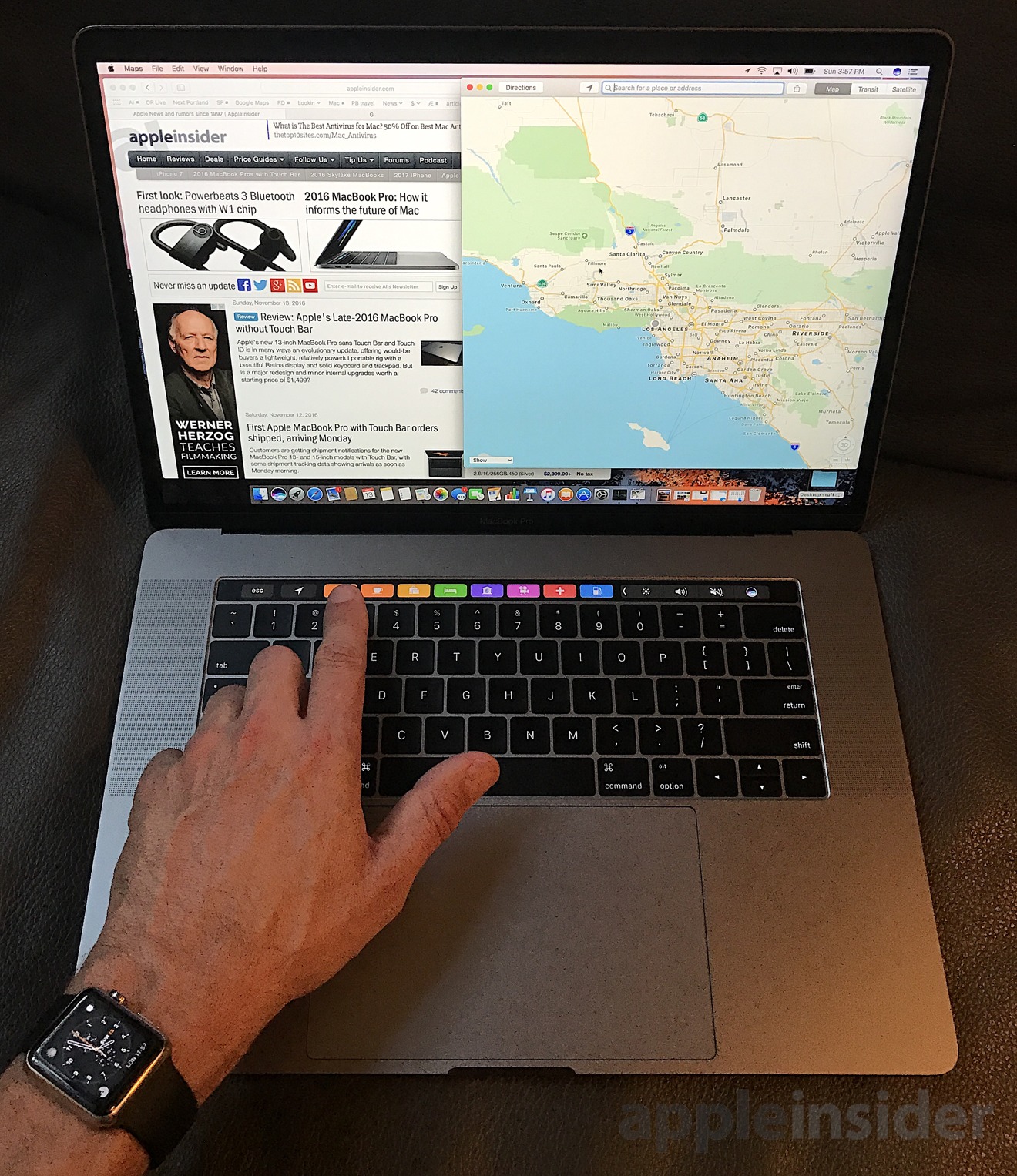

Starting at the end of 2015, Apple released iPad Pro. Rather than being a transition or convergence of iPad and Macs, it followed the same pattern Apple initiated in making a new, larger and more powerful version of its existing, popular iOS device. Apple separately enhanced its MacBook and MacBook Pro lines to focus on improving what makes Macs great, but it didn't ever mingle the two together to create a hybrid.

That's because hybrids in mobile electronics are typically worse than a product designed to be optimized for a specific task, an idea conveyed by Tim Cook using the phrase "refrigerator-toasters." There are probably not a lot of hardcore Mac users who rushed out to buy an iPad Pro to replace their notebook. That product was intended to be a more powerful iOS experience, not a way to down-sell Mac users.

In retrospect, it's hard for an intelligent and informed person to criticize Apple's strategic course, given its trajectory. While plenty of people insist that Apple should be following their advice, the fact is that Apple's approach has sold the most tablets and the most premium notebooks. Microsoft, which is often deluged with praise for following a different path from Apple in offering its Surface tablet-hybrid notebooks, has not come even remotely close to achieving similar sales.

At some point, if you're advising the winner of a game to follow the tactics of the loser, you have to stop and admit that your advice is really stupid, even if you manage to deliver your ideas in a way that is influential to people who read your work and nod along with you without any capacity for critical thinking.

Contempt of competence

The volumes of irrational hatred, contemptuous derision and frothy scorn that have been sprayed in the direction of Apple's iPad are quite incredible, given that actual buyers immediately began adopting Apple's modern vision of highly-mobile, slate-sized computing, and that those sales have consistently maintained a lead over all other rivals for a solid eight years, the entire span of time that tablets have sold in meaningful volumes.

From its original launch, criticisms were fired at nearly every aspect of Apple's new tablet. A review of the media's coverage of the new iPad in 2010 makes it clear that very few members of the media (or financial analysts) saw even a sliver of the real potential of the new product, and they didn't come around until Apple began reporting its sales figures.

Expressing a rare standout opinion, David Pogue of the New York Times noted of naysayers at its launch, "That [criticism] will last until the iPad actually goes on sale in April. Then, if history is any guide, Phase 3 will begin: positive reviews, people lining up to buy the thing, and the mysterious disappearance of the basher-bloggers."

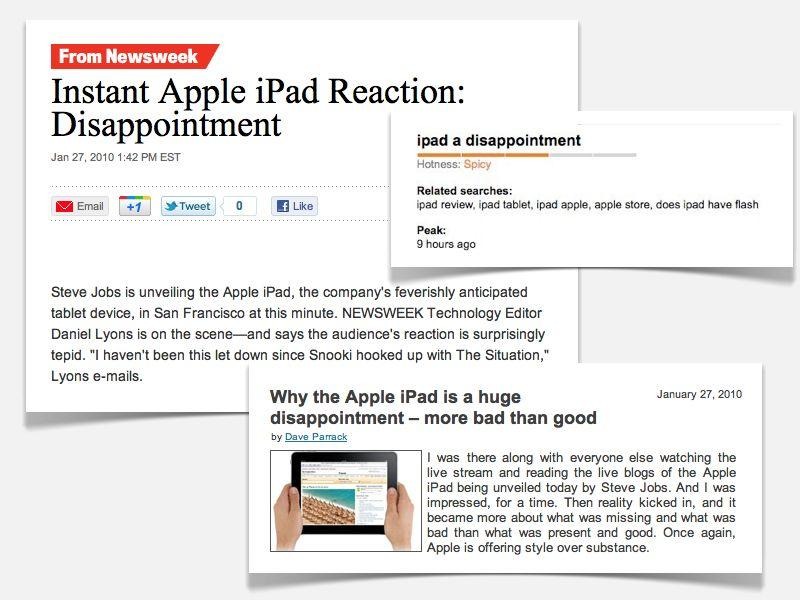

But by and large, the iPad was equated with Microsoft's Tablet PC and Amazon's Kindle and mocked as "over-hyped and under-delivered," while pundits demanded 2.0 features a year early. Hours after the iPad's unveiling, the phrase "iPad a disappointment" became a "spicy" trending topic as ranked by Google. Bloggers offered top ten lists of "reasons not to buy" the iPad.

Dan Lyons, then employed by Newsweek, had built a career of mocking Jobs. While he had plenty of nice things to say about free equipment Microsoft sent him to review, at the launch of the original iPad he sniped, "I haven't been this let down since Snooki hooked up with The Situation," adding in his "insta-reaction" that "Jobs himself seems tired and low-key. Speculation about his health, and its impact on Apple's ability to innovate, may only increase after today's event."

It's been so long, it's hard to remember that the people who today say that Apple can't innovate without Steve Jobs were less than a decade ago saying Apple couldn't innovate because of Steve Jobs. The best way to convincingly lie is to incessantly repeat overtly preposterous nonsense billowing from a crowd of other aligned liars, because those people will occasionally include an endorsement of your credibility among the lies they spew.

Lavish praise for imcompentent flops

A year after iPad shipped, it had immediately become the most popular tablet computing platform, handily outselling a decade of attempts by Microsoft and its partners— including HP, Dell and Samsung— to sell Windows Tablet PCs.

Yet many of the same bloggers and journalists who had derided iPad out of the gate turned around to express giddy anticipation for Google's Android 3.0 Honeycomb tablets in 2011, which attempted to deliver a similar form factor (albeit being heavier and thicker), promised functional support for Adobe Flash (without delivering, among a series of other sloppy software problems) and claimed to usher in new innovation and competition (although they really just attempted to drive prices higher), with devices that weren't even ready for sale and wouldn't be for months. Every last Honeycomb tablet was a huge flop.

Outside of Google's failed Android tablet platform, RIM's BlackBerry Playbook also basked in the giddy hopes of journalists seeking to find a dramatic rival for Apple's iPad, right up until it failed to make any real impact among the corporate users it was supposed to have wooed even before being delivered, solely on the basis of Blackberry brand recognition.

Palm's unfinished webOS TouchPad also enthralled critics, who then marveled at the potential suggested by Palm being acquired by HP. No doubt the company that had flopped around for a decade delivering tablet turds for Microsoft would be quick to pop out a wonderful TouchPad, despite webOS never making any progress as a phone.

Amazon attempted to reanimate the cadaver of RIM's PlayBook by house-branding a refreshed version of the device (from the same contract manufacturer) as Kindle Fire. Yet Kindle Fire hasn't really ignited anything and certainly didn't have the intended goal of stoking an Amazon-controlled mobile hardware platform. Further efforts by Amazon to build its own iOS with Fire Phone were a disaster, and even the remaining bits it salvaged, particularly Alexa's verbal interface, have largely delivered flash and hype without much useful heat.

More recent efforts by Google to turn Android tablets around have been profitless busywork. Intel's attempts to defibrillate Android tablets with its Atom chips failed despite incredible billions spent on subsidies. Android tablets are now nearly as forgotten as a strategic initiative as its Android Wear watches, robots and Google TV.

With new iPad Pro models expanding the capabilities of what an iOS tablet can do, with corporate partnerships expanding the use cases for mobile workflows in the enterprise and with new attention to iPad-specific productivity features in iOS 11, sales of iPads are again on the rise. And with users increasing adopting iPhone X as a more compact phone, we may see a further expansion of users augmenting their phone experience with the larger canvas of iPad.

But at no point will iPad focus on trying to be a Mac for global iOS audiences who increasingly don't know anything about the Macintosh.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

-xl-m.jpg)

-m.jpg)

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Chip Loder

Chip Loder

Thomas Sibilly

Thomas Sibilly

56 Comments

What I liked about the first iPad was it forced companies to improve their websites and most importantly those companies that had web-based applications.

I was in real estate and to use the listing service (ARMLS) or the contract/document service, etc., I had to have a Windows PC -Ugh! (I used a good, but somewhat, slow Parallels emulation SW on my iMac.)

To update the e-Key I had to have a landline in 2006! Sheesh!

Then along came the iPad on the heels of the iPhone and not only were the services more Mac friendly, but the iPad/iOS versions were a joy to use.

I think mainly, due to the fact that the apps/sw had to basically be built from scratch for iOS and b/c Apple provided the tools to build them to developers, the applications were closer to the Apple standard of elegance and ease of use. It forced the companies to 'raise their game' when it came to iOS!

That's what I remember most of the early iPad and hardly hear anyone mention it. It continues today, in that many tasks I do are easier on the iPad/iOS than on a Mac.

Great article -as usual, Daniel. :)

I watched the iPad announcement live. Not far in i said to myself, "yeah, I'm buying one of those." I did on launch day. Wasn't disappointed. I eventually moved on to an iPad mini, and use it daily. My wife loves her iPad Pro.

I said the same when I saw the Apple Watch reveal. It opened the MacBook Air I'm typing this one. Work I have to do later will be on my iMac.

I don't drive nails with a wrench. OTOH, I don't miss my Newton MP100. My recollection was it didn't work real well with my Duo230 (that I wore out in graduate school.)

It was clearly the best portable computer at the time: only a screen and touch control.

It still is.

Wasn't there also a Motorola Xoom...I remember being at a Super Bowl party and an ad came on for the Xoom and an engineer sitting next to me said, "that's the one I'm going to get." I remember thinking, nice guy but what a dumbass! :)