In 2010, Steve Jobs introduced the first iPad as a new product category between the smartphone and notebook. Born into ridicule, there's still a widespread misunderstanding of what iPad actually is, seven years later. Here's a look at why.

This segment follows part 1, which focused on the relationship between Apple's Mac and iPad products, and Apple's emerging strategy of marketing iPad as being "better than a computer."

A depressing start for iPad

Tech media contempt for iPad was intense enough to make it into Jobs' biography, which captured him as feeling "annoyed and depressed" by bloggers' snipes at its debut.

"I kind of got depressed today. It knocks you back a bit," Jobs confided with his biographer.

Hours after the iPad's unveiling, the phrase "iPad a disappointment" became a "spicy" trending topic as ranked by Google. Bloggers offered top ten lists of "reasons not to buy" the iPad. Adobe later launched a grousing campaign against iPad because Apple intentionally avoided inclusion of Flash middleware into iOS.

Other competitors bent over backward to marginalize its importance. Microsoft and its partners created dismissive talking points that regarded iPad as "not running a real operating system" and being only fit for "consumption," despite the fact that Apple immediately outsold its entire decade-old Tablet PC platform in a year and embarrassed the clunky new Slate PC Microsoft had just introduced in partnership with HP.

Beyond annoyed spite from affected competitors, there was another reason for all the naysaying of iPad: it was new, and forced users to change their expectations. This was by design.

Steve Jobs and the "uneasy" transformation of PCs to iPad

Jobs' vision for iPad, as articulated on stage at "All Things Digital" in 2010, suggested that tablets would have an increasing impact on computing in the future, inciting "unease" among existing PC users.

Asked if tablets "would ever replace the notebook," Jobs instead answered the question of what relationship tablets would have with PCs in general, using an analogy that described conventional PCs as trucks (oriented to their original use on the farm), and tablets as cars (put to use in urban centers in much higher volumes).

"Truck" PCs weren't going to go away, Jobs predicted, but "car" tablets would find a place among a larger number of users.

"This transformation is going to make some people uneasy," Jobs said. "People from the PC world, like you and me. It's going to make us uneasy."

While journalists were focused on the "tablet" form factor, Jobs' comments indicate a deeper thinking about what iPad was offering as a transformation of computing that would spark "unease." It wasn't just a conventional PC experience in a thinner, handheld device. Fortunately for Apple's fortunes, its competitors failed to grasp this, too.

iPad clones didn't copy the magic

Google and its Android licensees worked to create the impression that they would quickly displace Apple in tablets via a faster pace of open community innovation. Samsung rushed to put out an iPad-like device by the end of 2010, and announced shipment figures that were used to suggest Apple's "market share" was already greatly threatened, despite the fact that Apple kept selling more iPads.

Samsung's Galaxy Tab was later revealed to be a total flop in secret sales data revealed during the Apple vs. Samsung trial.

When Google's official tablet version of Android shipped in 2011, Android fans were quick to assume that premium widescreen tablets (with Adobe Flash support!) would leave Apple's iPad behind. Google itself expected its partners to sell 10 million Honeycomb tablets by the end of 2011. Instead, Apple's iPad kept selling while large, expensive Android 4.0 Honeycomb tablets from Motorola, Samsung and others failed to find interest.

After big, expensive Android tablets failed, Google sought to build incredibly cheap, small tablets. That effort was also a wash. Next the company put Android software on Pixel C hardware originally intended to run ChromeOS, resulting in a hybrid netbook like device that critics panned as unfinished. The company is now seeking to reanimate ChromeOS netbooks with Android apps. These shifting strategies haven't resulted in sustainable profits or in creating a viable tablet software platform for consumer or business apps.

Palm's HP TouchPad and Blackberry's PlayBook were also launched as attempts at getting in on iPad action, but both ended in failure. Amazon reanimated Blackberry's design with its own fork of Android, creating a vehicle for salvaging some of the work invested in its Kindle "iPod for books" and its later Fire Phone disaster. However after five years Kindle Fire has been neither significantly profitable nor developed a strong apps platform.

The worst tablet disaster, though, has to be Microsoft. It spent a decade trying to build a Tablet PC market by effectively creating a conventional PC notebook with stylus support. It then refreshed its efforts with Slate PC, which iPad stomped on right out of the gate. It has since tinkered with Windows tablets using a Zune touch interface, even crafting its own hardware business that's far less profitable or important than Apple's iPad.

The fact that Microsoft couldn't wield its Windows monopoly power to influence any leadership in tablets, and that Google and licensees of its "popular" Android platform couldn't figure out how to make any money from tablets either, raises the question of why buyers around the globe continued buying 40-60 million iPads every year at premium, non-discounted prices.

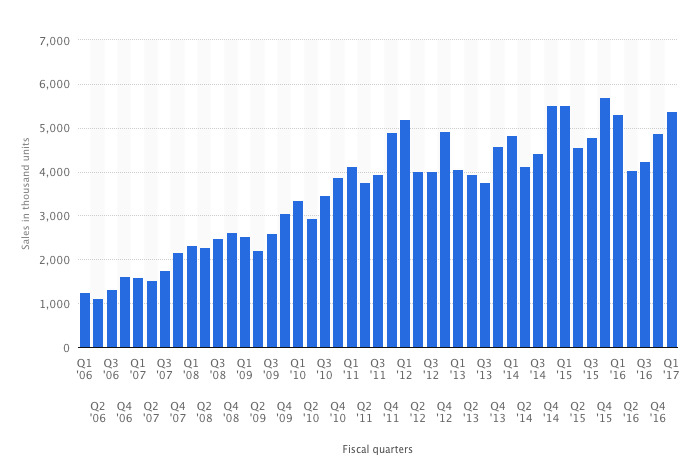

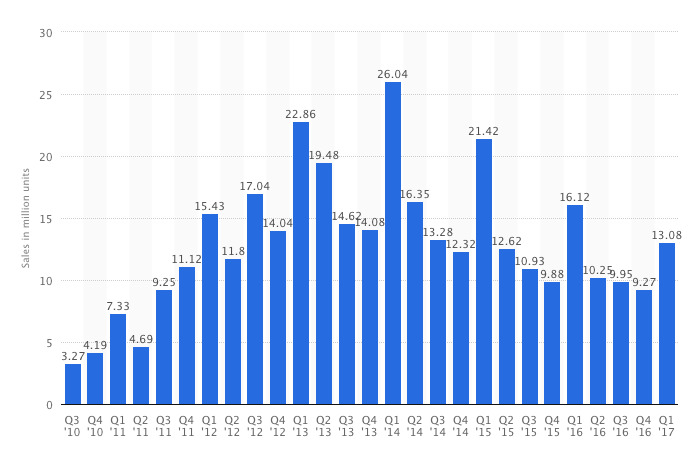

iPad outpaces Mac sales

The success of iPad is not only noteworthy in contrast to the trajectory of failed copies, but also when compared next to Apple's existing Mac computing platform.

Apple introduced iPad just as its Mac sales hit a quarterly peak of 3.3 million units. Its first reported quarter of iPad sales was nearly identical in units: iPad instantly doubled Apple's sales of computers.

While Mac sales continued to grow, they have consistently hovered between about 4 million and 5.5 million units each quarter since 2010. iPad sales rapidly ramped up into sales of 10 to 20 million units per quarter, peaking in 2014 with quarterly sales of 26 million.

iPad sales stopped growing after the release of larger iPhones in 2014, but the installed base of iPad users kept growing a much faster pace than conventional Macs. Since the beginning of 2015, Apple has sold 92.82 million iPads alongside sales of 38.93 million Macs.

While critics have scrambled to craft statics to portray iPad sales as troubled and failing, the reality is that iPad has sold many more units than Apple's Macs, generally generating more money at the same time. Apple obviously seeks to increase iPad sales, but its tablet sales remain the largest of any vendor and it continues to generate tablet profits that are the envy of the industry.Most remarkable about Apple's iPad sales is that they are augmentative to growing Mac sales

Unlike previous hardware "fads," notably netbooks and tweener Android tablets (like Google's Nexus 7), iPad sales have not only generated real hardware profits but have also created a real app deployment base that helps fuel the app sales that account for most of Apple's Services business growth— now itself a $7 billion business that's larger than iPad hardware.

Most remarkable about Apple's iPad sales is that they are augmentative to growing Mac sales. Rather than trading its high end conventional PC sales for lower end tablets (as many PC makers have inadvertently done), Apple has effectively tripled its total computer sales by selling iPads to new users or for use in new roles, while also cultivating Mac sales among users who prefer its more complex, powerful and flexible environment.

While commonly praised as an inevitable and desirable outcome, the hybrid "two in one" convergence products that Microsoft and many of its licensees are trying to sell actually compromise in the wrong areas, resulting in products that are heavier and more complex than an ideal tablet but also can't command the same premium as a performance-oriented PC.

Why iPad outperformed other attempts at transforming the PC

Critics initially worked to portray Apple as poised to lose out in the "tablet transformation," as PC and phone makers threatened to produce more Windows or Android tablets than Apple could sell. They were wrong, as Apple kept making more money at tablets than anyone else.

As tablet sales plateaued and then began to fall, critics began dismissing the entire tablet category as an irrelevant, technological dead end. Rather than simple tablets, they insisted that people wanted whatever Microsoft was selling, which now happened to be laptop-tablet hybrids or "two in ones."

However, that was not really true either. Microsoft's own Surface line has struggled for years to build a hardware business as its smartphone efforts failed; it has hit a ceiling of dollars and units that hasn't appreciably grown over several years. Microsoft's Surface ceiling was far lower than iPad's.

A vocal minority likes to talk about why they prefer Surface as a product, but globally it's clear that Microsoft's vision for the future of computing is far less captivating than Apple in terms of both units and dollars.

When Apple launched iPad Pro it took direct aim at the premium "highly mobile" tier occupied by Microsoft's Intel-based Surface Pro. It immediately outsold Microsoft's hybrid offerings, generating greater sales at higher profits.

Microsoft shoots at mobility, misses

Microsoft's initial competitive effort targeting iPad envisioned an ARM-based Windows PC (Surface RT), which turned out to be a huge flop.

Particularly over the last year or two, Microsoft has shifted away from Surface comparisons to iPad and repositioned Surface Pro as a MacBook alternative. Microsoft supporters were quick to double down on the retreat back to conventional PCs by belittling Apple's ultra light MacBook Pro introduction while expressing delight with the "innovation" Microsoft served up in an ultra premium new Surface Studio PC introduced with a new physical dial UI controller.

Such a subjective, emotional comparison is necessary to flatter Microsoft because by any factual, objective comparison— of sales units, revenues, profits, or market platform power or ecosystem value— Surface is a huge, expensive failure while iOS continues to gain relevance and revenues in the enterprise and among consumers.

In its launch quarter, Microsoft shipped about 30,000 Studio PCs, and its total Surface revenue has hovered at or below $1 billion for years. That barely qualifies a hobby in the global market for computers.

IBM and SAP are both creating vast global consultancies centered around the development of new tablet-oriented iOS business workflows for their enterprise clients. Very little is happening in the Surface world apart from PR.

Microsoft's attempt to target Mac notebooks with Surface is reminiscent of its earlier efforts to clone Apple's iPod with Zune while missing the larger picture of what was going to happen with iPhone and iOS.

However, looking only at Apple's own transformation, it's easier to understand how iPods evolved into iOS devices than to visualize how Macs could stick around as trucks while iOS tablets outpaced the sales volumes as the new post-PC computer.

Its also easy to lose awareness of what's happening because so many Apple critics are desperately shouting that tablets are dead— so vocally that they fail to see what's actually happening in personal computing.

A better car without some truck parts

Jobs' cars and trucks analogy also depicted the development of new features (including an automatic transmission) that made more sense to car buyers than truck users. This was a very apt detail that many missed at the time.

That's because so many critics were blindly focused on criticizing features that iPads lacked that they failed to consider that cars lack a lot of the features of trucks by design. Trucks for farm use might include a winch and a towing hitch, and make cargo bed space a priority, for example. Those things are not very important to cars tasked with moving people.

Some features developed for car buyers have eventually trickled into truck development, particularly interior comfort, radios, climate control, navigation, automatic transmissions and so on. Others features have migrated in the opposite direction, such as trucks' four wheel drive and raised "command seating" making their way into hybrid passenger cars. Apple's clear separation of iPads and Macs as product categories is unique among its competitors

That cross pollination is also evident in Apple's development of features for iOS and macOS. However, Apple's clear separation of iPads and Macs as product categories is unique among its competitors. Apple has resisted calls for full "hybridization" and cross over of many legacy Mac features to iOS.

This isn't arbitrary; it's facets of a strategy that caters to users who aren't interested in learning to navigate the complexity of a conventional computer. It requires understanding the parts of the PC UI that are inscrutably confusing to non-technical people and simply eliminating them. It also involves starting from scratch in some areas to build a better design.

The Post PC processor

Microsoft's original goal for Surface was oriented around moving Windows from Intel to ARM chips, copying Apple's migration from Intel Macs to ARM iOS devices. However, Microsoft skipped over Apple's radical rethinking of the user interface, preferring instead to simply sell its existing Windows Metro UI on new ARM devices.

This failed spectacularly (as we noted it would) firstly because it confused users with why legacy software wouldn't run on Surface RT products, and secondly because it disappointed with slower apparent performance on ARM chips compared to Intel-based PCs.

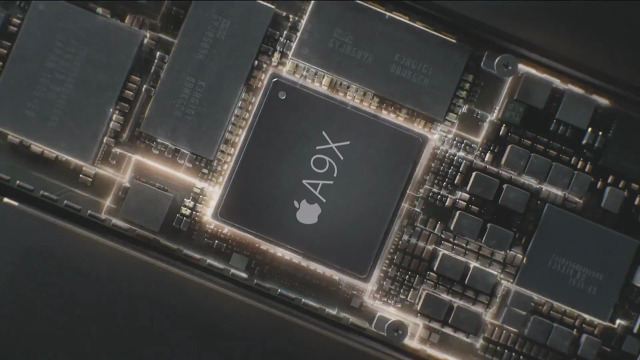

Apple's migration to "cars" with iPad radically rethought the user experience to recalibrate the expected performance of its tablet. It did less, but on purpose. This now allows Apple to boast that its ARM-powered iPads are "faster than most Intel-based notebooks." iPads also cost a lot less to build, can use simpler cooling systems and require much less RAM, contributing to better battery life.

This is comparable to the transition from trucks to crossover SUV cars: rather than delivering a truck chassis for a car (which would deliver terrible fuel efficiency and an uncomfortable truck-like ride), luxury crossovers built truck-like SUV experiences on a car chassis. This isn't as "powerful" as a truck in many respects, but delivers a new experience that can be better than a truck (in comfort, handling and efficiency) and superior to a car (in cargo capacity and raised seating).

In the automotive world, successful new vehicle categories (such Chrysler's minivan or BMW's luxury SUV) are quickly copied by rivals. In the tech world, copying Apple is complicated by the fact that other vendors are largely dependent upon a third party OS vendor, either Microsoft Windows or Google's Android, and therefore can only follow the limited vision of those alternative platforms.

Microsoft couldn't figure out how to support Windows on ARM, while Google has rushed to support Android on everything, resulting in fractionalization issues and dead ends of support for architectures like Atom. Apple's iPad and iOS are not only highly optimized exclusively for Apple's own A-series Application Processors, but those chips are also specifically optimized exclusively for iPad and iOS.

The Post PC user Interface

Another aspect of "truck PCs" that Apple correctly left behind when building its "iPad car" involves the user interface. Apple actually developed an entirely new user interface for iPhone built around multitouch rather than the precise mouse pointer of desktop computers like the Mac.

Both Microsoft and Google found it hard to shake free from legacy PC user interface concepts. Windows Mobile was a small PC. Google's early Android prototypes were initially button-oriented, then shifted to a trackball interface. By 2011, Google was reintroducing a Windows-like desktop on tablets.

PC maker Samsung thought it was novel to add a stylus pointer to its Note mini tablet. Microsoft added a keyboard and stylus to its Surface machines, and its latest Surface PC added a physical dial control to navigate interface menus.

Apple has staunchly resisted mixing the legacy mouse pointer into iOS for navigation purposes. Precise text input (via 3D Touch press on the iOS virtual keyboard) & Apple Pencil are examples of adding mouse-like pointer control to iOS in ways that are independent from navigating the user interface.

When it developed tvOS for Apple TV and watchOS for Apple Watch, it similarly rethought the interaction model for each, avoiding the mistake of simply merging a PC with a TV or wearable. Contrast the failure of Google TV and its keyboard remote control, or the nutty button controls and keyboard input on Android Wear watches.

Strict design of an appropriate user interface for a new product category— and resistance to carry forward an old interface model that doesn't really make sense anymore— is part of the "uneasy" transition Jobs described back in 2010 for PC users new to iPad.

It's like moving from a manual shift to an automatic transmission. It can require more sophisticated technology, but it also results in a user interface that is more broadly accessible to new types of users, even if existing users might scoff at the "simplicity" of the easier-to-use system.For a new generation of users familiar with iPhone, iPad is readily accessible in ways that conventional PCs (including Macs) simply aren't

For millions of PC users, iPad may similarly seem too simple and not "powerful" enough. But for a new generation of users familiar with iPhone, iPad is readily accessible in ways that conventional PCs (including Macs) simply aren't.

In particular this applies to employees in the enterprise, where new workflows on easy-to-use, power-efficient tablets make far more sense than general purpose notebook computers, which are good at doing "more" but less capable at being simple to use and almost effortless to manage.

The Post PC display resolution

Apart from its navigation and interaction decisions, Apple's choices for the iPad display are also noteworthy. Both Google and Microsoft have advanced wide screen tablets oriented more for television and movie watching, or as a holdover from the legacy PC notebook. Apple went with a more square format that better replicated a notepad or magazine.

After several generations of failures, Google's abandonment of its wide screen to instead copy iPad's more square ratio (in Nexus 9, and then Pixel C) says something about Apple being right from the beginning. Simply picking up a Surface and trying to use it as a tablet is also a quick reminder that iPad got the ratio right and Microsoft just wanted to try new things.

Apart from the display shape, Apple also made a smarter use of increased resolution. While Android and Windows had been using higher resolution screens to show an increased "desktop area," Apple made a major, novel jump to Retina Display resolutions where the same user interface was simply rendered in more crisp detail.

iPad mini also introduced a smaller form factor that didn't shrink "the desktop" (as tweener Android tablets did), but rather scaled down the standard iPad display into a smaller device, rendering existing iPad tablet apps identically on a smaller screen. iPad Pro similarly increased the form factor, enabling new screen splitting features that put multiple apps on screen at once.

This year, it appears Apple will again scale the 12.9 inch iPad Pro down to a roughly 10 inch "Pro mini" form factor, again retaining easy compatibility with existing apps. These changes are all intended to respect the iPad's app development guidelines, making it easy to deploy apps to the iPad platform even across new device types.

In both Windows and Android, an infinitely scalable array of hardware screen sizes and ratios means that developers have to account for all this variation, making it easy to just ship a phone app that "autoscales" to fit tablets without actually taking full advantage of the tablet's larger screen. That's helped to keep Android tablets from growing into a real app platform.

Key to Apple's ability to sell tablets is that it isn't selling iPad as a PC device, but as a new platform.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

-m.jpg)

Wesley Hilliard

Wesley Hilliard

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Andrew O'Hara

Andrew O'Hara

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

37 Comments

"Jobs' vision for iPad, as articulated on stage at "All Things Digital" in 2013, suggested that tablets would have an increasing impact on computing in the future, inciting "unease" among existing PC users."

Steve Jobs passed away in 2011, The D8 conference was in 2010. The video linked was posted on youtube in 2013.

You cannot compare iOS to Mac. The second is so much, much, much more better (flexible and powerful in all software and hardware, including ports).

IMO The "post PC" world is still chaotic and playing out what it will be. In the US, trucks and SUV are still the best sellers. Will "post PC" turn out less so than imagined? For most people I know the iPad is the go to home internet communicator(email/internet)/work reference document reader device(PDF,form filler-outer). Voice /text device is iPhone/Samsung etc, which seems to be reaching a plateau in what they can do... i.e. the churn rates will grow longer before upgradea(ala iPad?). For 'work product' it is still the PC/Mac. But also... are not schools more and more turning to Chromebook devices? Then there is the video consumption devices like Apple TV/ Roku. Then there are what seems like 'home services devices' like Echo.

What all this means... don't have a clue... but it seems to me if someone can consolidate this to a few multipurpose devices... or just one main device(computer, server like storage, wifi broadcaster, house services device) with some ancillary interface devices... they may have a winner. IMO Apple is best(if not the only one) positioned to do all that, if that is a better "post PC" path. I also find it interesting Warren Buffett has bought a lot of Apple stock... has he seen behind the curtain? Why is he so sure iPhone will keep Apple revenues so high for the long term investment he is famous for?... interesting times.

whew... what happens when you have a bout of insomnia.

OK... The cars vs trucks analogy was appropriate 10 years ago. Times have changed. Connectivity has progressed to the point of making DVD drives obsolete and a variety of ports unnecessary and plus, fanless processors are now multicore and 64bit and they rival the power of low end Intel processors. Today, the only reason that an IPad cannot perform the same tasks as a MacBook are restrictions placed on its OS by Apple as well as the lack of a USB-C port. Otherwise, simply adding a touchpad to the IPad Pro's keyboard would pretty much knock the low end MacBook right out of the water.

Siting execution failures by Google and Microsoft says nothing about the concept of a 2 in 1 device. That's what Google and Microsoft do best: fail.

The appropriate analogy is Jobs' statement that users did not want a big bulky phone. He was right. But, as the technology progressed, his phone became less of a phone and more of a computer and users DID want a big bulky "phone". It's not that Jobs' was wrong. He wasn't. But, he was talking about the state of things as they existed. Times change.

I strongly doubt that Jobs' would have held on so tenaciously to a 4" IPhone like Apple did until the '6+' finally came out. Likewise, I doubt that he would be using his 'cars and trucks' analogy today. Instead he would have Dylan on stage singing about times and how they are a changin.