The long wait for official third party apps on the iPhone is over. From the moment the original iPhone was released, critics complained about Apple's closed platform and insisted that it could not meet their definition of "smartphone" because it couldn't run software created by other companies. In this segment, we'll take a look at the Apple's iPhone software development kit, the App Store, and iPhone 2.0's third party apps themselves.

Inside iPhone 2.0: the new iPhone 3G Hardware (Last Thursday)

Inside iPhone 2.0: iPhone 3G vs. other smartphones (Last Friday)

Inside iPhone 2.0: the new iPhone 3G Software (Monday)

Inside iPhone 2.0:Â iPhone OS vs. other mobile platforms (Tuesday)

Inside iPhone 2.0: the new iPhone App Store (Today)

Inside iPhone 2.0: MobileMe push messaging (Tomorrow)

The road to the iPhone SDK

Shortly before the release of the first iPhone, Apple announced a standards-based web platform for creating relatively simple, interactive web apps. Developers hoping to tap into the full power of the iPhone wept bitterly, although some took advantage of the web platform to deliver impressive or useful iPhone web apps, such as Facebook (below left) and the MuniTime NextBus client (below right), required in San Francisco because transit here operates with the frequency of a solar eclipse.

For the next several months, the only way to add more significant applications to the iPhone was to "jailbreak" it, which worked around Apple's security features to enable other arbitrary code to be copied to the unit and run. However, jailbreaking the iPhone also complicated every software update, as Apple continuously made changes to its software and addressed general security holes that the jailbreak community had been exploiting to enable third party apps.

Jailbreak apps potentially undermine the security, reliability, and battery life of the iPhone, although Apple's own iPhone 2.0.0 software has done a bang up job of violating all of those things itself as well. Unofficial apps will likely continue to exist, in part because they do not require approval from Apple and therefore are not limited by the policies the company has set up to protect users, its partners, and the usability and reputation of the iPhone itself.

Most users will likely stick with those apps officially available through Apple's iTunes Apps Store because it's simply much easier and requires no diddling. Most developers are also going to be more interested in getting paid for their efforts than handing them out for free with complicated support instructions. Still, there are a variety of apps that are currently only available outside of Apple's official Apps Store, either because they directly access hardware in ways that are not supported by the official iPhone SDK (such as video recording, or the NES games console emulator) or because they offend Apple's policies, such as the NetShare tethering app that was pulled from the Apps Store, presumably due to contention with AT&T's mobile service agreement.Â

The iPhone developer program

Apple's official iPhone software development kit (which also works with the iPod touch; we'll refer to it as the "iPhone SDK" just to make things simpler) supplies enhancements to the company's existing Xcode integrated development environment that allow developers to write, debug, test, optimize, and compile software that runs on both handhelds.

The tools work nearly identically to those used to develop applications for Mac OS X, which is no surprise because the iPhone OS and its development frameworks are a fraternal twin birthed from the same corporate womb. The main difference is that while Apple does not limit anyone from churning out Mac OS X apps, it has taken steps to prevent open distribution of iPhone apps; they're officially only available via iTunes and through the Apps Store on the iPhone itself.

In order to get apps into Apple's official store for distribution, developers must apply for participation in Apple's iPhone developer program, pay a nominal $99 fee, and submit their applications to Apple for approval. Apple gets to approve (and revoke) all apps in its store, and takes a 30% cut of the proceeds in consideration for marketing and handling the distribution and billing of all iPhone software.

iPhone SDK vs. other smartphone platforms

This has raised considerable ire from pundit critics who have tried to suggest that the iPhone SDK was a draconian plot dreamed up by Steve Jobs to deprive users of free software and profiteer upon the backs of participating programmers. Those critics were apparently unaware of the fees charged by every other smartphone development program on Earth, as well as the common understanding that mobile devices simply can't reliably or securely run software from unknown, untrusted sources.

The PC desktop is a malware mess because it's simply too easy to distribute malicious (or incompetent) code, and there's no real way for users to trust software they find. While Apple gained lots of attention for its efforts to deploy mandatory certificate signing on all iPhone software, every other reputable mobile platform vendor is also trying to deliver the same thing. They just charge developers more while offering them less in terms of marketing and merchandizing than Apple does.

For example, Microsoft charges Windows Mobile developers closer to $500 to participate, and then takes half of their revenues. Developers can also take their Windows Mobile apps to other mobile software distribution stores, but Microsoft's recommended Handango takes at least 40%, and expects larger developers to pay it 60 to 70% of their revenues. Most other online mobile software distributors charge developers around 50% of their revenues to sell their work for them.

RIM, Symbian, Java, and Qualcomm's BREW all have their own certificate signing programs, which cost more to get started with, are more complicated and expensive to use in signing apps, and frequently involve high testing fees that can in some cases approach $1000 per application submitted. Apple does not charge any additional fees on a per app basis.

Instead, Apple has set up its iTunes software store to merely pay its own way, following the same strategy that made reasonably-priced audio and video content available for the iPod and the Mac. Apple operates its iPhone software store as a tool to foster high quality, low cost apps for the iPhone so users will have additional reasons to buy Apple's hardware. Company executives have even expressly stated that they do not run the store with the goal of making big profits on software sales.

Apart from RIM's BlackBerry and Danger's Sidekick (now owned by Microsoft), most mobile platform vendors do not share Apple's hardware-centric business model and therefore have to pay for their operating system development and platform maintenance by charging developers lots of fees. That's bad for developers, and in turn impacts end users with higher prices.

The iPhone Apps Store

Using the iTunes Store to deliver iPhone apps is both clever and convenient, as most iPod users already have an account and are familiar with how it should work. You can buy apps individually or in an iTunes shopping spree using a cart. If you buy apps through the Apps Store app (below left and middle) on the phone itself, you have to enter your iTunes password for each new transaction (below right), which is pretty much identical to the process for browsing and buying other media from the iPhone's WiFi Store.

If an app is marked as mature, you are also somewhat comically warned "this product contains material that may be objectionable to children under 17" (below left). We found this warning while downloading iPint, a free mini-game that involves sliding a beer down a bar to your friend (below middle), and then pretending to fill up your iPhone's screen with beer so you can pretend to drink it in celebration (below right).

On page 2 of 3: This just in: software updates; Early adopter app kinks; What you can expect from third party apps; and How much does it cost?

The unique aspect of software is that it gets updated frequently, and Apple's mechanism for updating apps is very slick, at least conceptually. Currently, every time you update an app it deletes the old version and then annoyingly installs a new icon in some other random place in your phone's pages of app icons, rather than replacing the old icon with the new one. Hopefully, this behavior will be fixed soon, as having to rearrange your icons every time there's an update really gets irritating. This behavior was not fixed in the 2.0.1 update that just came out, but it does make it slightly easier to fix your icons after they are messed up, as it now allows you to drag an app's icon across multiple pages in one step. We'd rather it just replace the old app with the new one though.Â

When the iPhone finds that new updates are available for any of your installed apps, it throws a numbered badge on the Apps Store icon. The only way to remove the badge is to install the updates. This can also be irritating as notification badges really scream for attention; it would be great to have a way to ignore updates you'd prefer to install later. At the same time, the app notification and updating process is extremely useful and well designed, addressing the problem of version control in a simple and intelligent way. It's like having VersionTracker built into your computer. From the App Store's Updates tab, you can browse a list of apps that have updates available (below left), pull up their information page to see what has changed (below right), and install each individually or mass update them with a click on Update All.

While the update process seems to work pretty well, there are interface bugs in iTunes that often result in an incorrect number of apps being listed as having updates available. Many times the apps remain highlighted as needing an update even after you've downloaded them all. Sometimes an app will appear in the update list twice, as it did with WordPress and then AIMÂ (below). The iPhone's App Store icon also seems prone to fall out of sync in the update count after performing all updates through an iTunes sync. Despite the interface glitches, the updates themselves seem to install properly.Â

Early adopter app kinks

Apart from those niggling update issues, the main issues with using third party apps relates to the fact that developers have only had their apps in the wild now for three weeks. Several apps seem buggy or erratic or prone to crash on startup, while others begin to install and then disappear, or conversely reappear after you try to get rid of them. iTunes sometimes also fails to copy over apps sometimes, but usually can get things moving on the second try. The 2.0.1 update has greatly improved the overall experience however. Many third party apps that seemed very flakey work fine under 2.0.1.

In the case of dysfunctional apps that won't open on the device, deleting the offending app and re-syncing it over from iTunes usually helps, but make sure you have done a backup of your iPhone after buying any apps from the unit directly, or else you'll have to write Apple to request the ability to download any purchased apps again. The iTunes Store does not recognize that you've already bought an app and allow you to download it again, it only asks if you're sure you want to purchase it again. On the device itself, purchased apps in the Apps Store are badged with an "installed" tag rather than any install option, but still can't be downloaded again.Â

Similarly, if you have upgraded an original iPhone to the 2.0 software and purchased apps, you'll need to upload those purchases to iTunes before you can copy them to the new iPhone 3G, and of course the same applies to purchases made on an iPod touch. This process would be simpler if Apple allowed users to download any apps they have purchased on demand at any time.

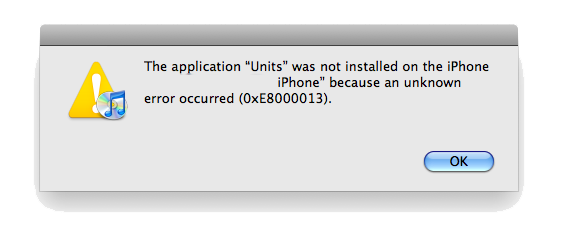

We also noticed that after uploading lots of apps up to iTunes from one device, syncing them down to another iPhone resulted in a mixed up jumble of icons on the second device, rather than an orderly set of home pages that matched our first phone. One app even failed to copy over on the first try, presenting an error message instead (below). It copied over on the second attempt. While most users are unlikely to have multiple iPhones, being able to keep icon positioning in sync between devices would be a nice touch.

What you can expect from third party apps

Of the 500 apps that appeared at launch, several were quite impressive and there was a good number of useful free programs. The number of available apps has since surpassed 1000, but the initial selection is certainly still a mixed bag however.Â

Despite the fears that Apple would disallow everything apart from apps from major partners such as Sega, EA, AOL, and other large developers, the Apps Store is littered with junk apps, including a number of nearly worthless utilities (such several "apps" that offer to turn the iPhone into a flashlight), a variety of light duty programs that act mainly as advertisements, a series of "apps" that are just public domain ebooks or static transit maps, and several others that are nothing more than a glorified (or in some cases, simplified) web page.

Outside of the junk, there are a few standout apps that really shine and make the iPhone dramatically more valuable. There are an increasing number of impressive, console-style games; a great selection of social networking clients; lots of very useful utility apps; and a good selection of news and information apps. Most of these look great and behave like slick iPhone apps rather than the ugly junk applets available for most smartphones.Â

Additionally, the update mechanism and general understanding that updates will be free means that good apps are continually refined into great apps. Developers seem to be paying close attention to user comments and feedback and are using these to regularly improve their iPhone offerings. This in turn enables smaller developers to start a project and incrementally advance it while receiving ongoing support, rather than having to underwrite a massive, speculative software project without any real input from users. This new model is a refreshing change from the annual tweaks to big software suites on the desktop.

How much does it cost?Â

Even more impressive is the fact that most of the best apps are free, as they're often related to service and are more interested in lots of eyeballs than in collecting a few bucks. Loopt, Facebook, MySpace, and Yelp all offer free clients that are handier than browsing those sites on the web. Evernote also has a free client for uploading notes, audio recording and photos into its server based notebook archives. The free Shazam listens to songs playing in the surrounding environment and lets you identify and find them. AP, Bloomberg, Getty Images, and the New York Times all have free clients for browsing news and current events. AOL Radio and Pandora provide free clients for finding and listening to online radio streams.

Paid iPhone apps are rarely more than $10, and many are less than $5. EA, Sega, and independent Mac developers have churned out a number of highly addictive games for $10 or less with impressive graphics, sound, and intuitive accelerometer controls. Other high quality games are inexplicably free, such as the difficult to put down Aurora Feint, which takes a basic screen clearing puzzle and turns it into a resource collecting game where you level up and buy new abilities that change the game as you play.Â

Apple set the tone for pricing by releasing its excellent iTunes Remote app for free and selling its high quality Texas Hold'em card game for $5. Remote turns the iPhone or iPod touch into a remote controller for Apple TV and Macs or PCs running iTunes, allowing you to start, pause, skip through audio or video playback, search and browse playlists, view cover art, and adjust the volume, all without any delay or hesitation. It even acts as a WiFi wireless keyboard when used with Apple TV.

Texas Hold'em is an enhanced version of Apple's popular iPod game. It still costs the same $5 as the iPod version, setting a low threshold for typical pricing in the Apps Store even for classy, professionally designed software. While the company wants apps to be priced low, it also encourages developers to charge something for their apps, in order to keep developers financially motivated to introduce new apps, and of course so Apple itself can earn something for publishing and marketing their apps.

On page 3 of 3: A smartphone software price comparison; iPhone as a handheld game console; and What about the web?

The first 40 iPhone apps we downloaded cost us a grand total of $32. In comparison, a quick look at Windows Mobile software offerings found $444 worth apps at the top of the charts that simply aren't necessary with the iPhone:

- $110 of popular titles that are completely unnecessary on the iPhone, including a memory manager for optimizing the tiny bit of RAM installed on those phones, a system cleanup and maintenance tool, a file backup utility, and interface patches for correcting problems in Windows Mobile itself.

- $334 of top selling Windows Mobile apps supply functions included on the iPhone for free, such as a world clock, a "real email client" for replacing Microsoft's Pocket Outlook, a photo browser, a contacts app, an MP3 player, a movie player, a TV player, a calculator, a full screen keyboard, a PDF reader, and a notes application.

Even worse, there was really very little exceptional software available for Windows Mobile, particularly among anything that was free. Other platforms have similar problems with overpriced, underwhelming software. Qualcomm and Verizon try to sell low quality BREW applet games to their mobile users for a monthly rental fee. Palm OS titles range from $15 for a basic Soduko game to $37 for the "Pocket Tunes" MP3 player.Â

The problem with mobile software is that there has never been a functional market to pay developers enough to keep them interested in refining their apps or doing anything really valuable. When useful mobile apps have appeared, they end up being very expensive because developers have to recoup the most they can from those with no price sensitivity because everyone else simply steals their work. The DRM Apple uses in iTunes allows developers to set low prices that bring in a reasonable return when titles are sold in volume, and virtually eliminates casual piracy. That means users and developers both win, at the expense of thieves who would prefer to steal apps instead. Â

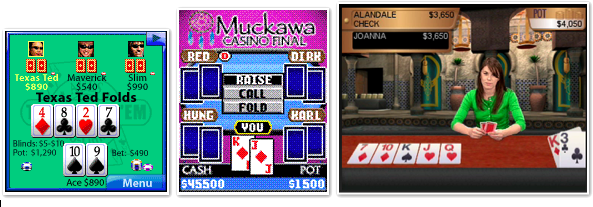

As an example of what you get compared to what you pay for, here's Texas Hold'em for Palm ($20, below left), for Verizon BREW ($8.50, below middle) and for the original iPod ($5, below right).

iPhone as a handheld game console

The iPhone version of Texas Hold'em costs the same $5, but plays in both portrait mode with video of animated characters (below left), or in landscape in a table view (below right). You can swap between game styles by tilting the device. It also supports multiplayer gameplay.Â

The iPhone's apps (and in particular games) are really well beyond the league of most smartphones, and can readily be compared to handheld console games. That idea the the iPhone would be a competent alternative to the Nintendo DS, Sony Playstation Portable was received as highly controversial just a few months ago, but gaming legend of John Carmack of id Software recently described the iPhone as "more powerful than a Nintendo DS and PSP combined," and has noted that his company has multiple titles in development.

That being the case, the typical $5 to $10 price point for iPhone games is particularly amazing when compared to existing handheld console games, which usually sell for closer to $20 to $40 or more, and can rarely be downloaded over the wire for immediate gameplay.Â

Sega's Super Monkey Ball, a popular $10 game for the iPhone, was at least $20 for the sidetalkin' NGage (Nokia's failed attempt at delivering a hybrid game console and mobile phone), but NGage reviewers still complained, "The choppy animation and lack of analog controls really suck the fun out of the game." The game costs $40 on the Sony PSP and $20 on the Nintendo DS. The game's graphics on the iPhone (below middle) are similar to the PSP console version (below bottom) rather than being in the league of other smartphone games like the NGage (below top left) or the simplified "Super Monkey Ball Tip N Tilt," $10 mini-game version that plays on regular Symbian smartphones such as the Nokia N95 (below top right).

Â

What about the web?

The greatest disappointment in the Apps Store is that it only lists standalone Cocoa Touch apps. While it's certainly nice to be able to install new apps that can work offline, many or perhaps most of the iPhone apps require (or desire) a network connection. That makes them only slightly more advantageous than the wide selection of free web apps available for the iPhone, which remain unlisted in the Apps Store.Â

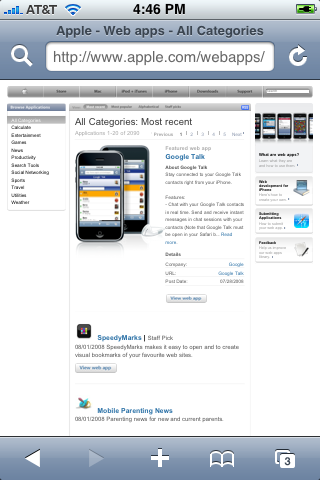

Even more oddly, Apple only provides a listing of these 2,000 web apps on its strangely non-iPhone optimized web apps page (below), which can be somewhat clumsily browsed via Mobile Safari on the iPhone, but not with the slick polish of the Apps Store.Â

Apple should immediately add a listing of these highly functional apps to a special web section of the Apps Store, making it easier to setup links to these useful, iPhone-savvy web pages. Doing so would fill out some missing holes and might remove some of the interest in dumping junk apps into the App Stores' paid listings.Â

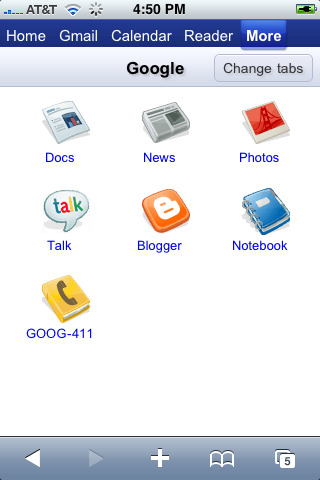

Among the iPhone-optimized web apps available are nearly all of Google's online offerings, including a Docs reader, Talk IM, News reader, RSS feed Reader, Gmail, Calendar, and Photos (below). There's also plenty of unit and currency converter tools and specialized calculators; over 500 online games; a variety of mobile-optimized news and sports sites; lots of dictionary and reference sites; and plenty of search, shopping, travel, webcam, and weather related sites.

With iPhone web app utilities, you can test your Internet access speed, track packages, and O2 (but not AT&T) even provides an MMS reader. Setting up a web app doesn't require any fees or approval from Apple, and properly developed web apps should work on any standards-compliant web browser (not just the iPhone). Why the pundit community has blackballed iPhone web apps is nearly as puzzling as why Apple has hidden them behind a really poorly conceived, iPhone-hostile web page that users have to seek out.

We'll be reviewing individual iPhone apps in greater detail in the future. Coming up next, we'll look at the last major feature unlocked in iPhone 2.0: push messaging.

Prince McLean

Prince McLean

-m.jpg)

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

Wesley Hilliard

Wesley Hilliard

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Sponsored Content

Sponsored Content

22 Comments

Great overview, but one point: The App store certainly does remember that you've already bought an app.

I accidentally deleted Crash Nitrokart ($9.99) and WordPress (free) mysteriously disappeared as well (not sure why). They were not in the app tab in my iTunes, so I went to the store for the free wordpress app first, and after going through the whole process, it says "you have already purchased this item, do you want to download it for free again"

Then I went for the 9.99 Crash Kart game, and sure enough, it remembered that I bought it before and offered me a free download.

Great overview, but one point: The App store certainly does remember that you've already bought an app.

I accidentally deleted Crash Nitrokart ($9.99) and WordPress (free) mysteriously disappeared as well (not sure why). They were not in the app tab in my iTunes, so I went to the store for the free wordpress app first, and after going through the whole process, it says "you have already purchased this item, do you want to download it for free again"

Then I went for the 9.99 Crash Kart game, and sure enough, it remembered that I bought it before and offered me a free download.

I think Prince was just saying that the iPhone Software does not remember the placement of application icons on the iPhone's home screen after each maintenance update. This means you have to continually reorganize your icon placements after individual app updates are installed.

Best,

Kasper

I think Prince was just saying that the iPhone Software does not remember the placement of application icons on the iPhone's home screen after each maintenance update. This means you have to continually reorganize your icon placements after individual app updates are installed.

Best,

Kasper

Great article! Once again shows re. costs charged to developers on other platforms, how Apple is thinking different. Loving my 3G and awaiting new MPB announcement.

I think Prince was just saying that the iPhone Software does not remember the placement of application icons on the iPhone's home screen after each maintenance update. This means you have to continually reorganize your icon placements after individual app updates are installed.

Best,

Kasper

Oh yeah, he said that too, and I agree with him. But he also said the following, and I think it's important to clarify it, because we don't want to give the Apple haters fuel for their fire!

... make sure you have done a backup of your iPhone after buying any apps from the unit directly, or else you'll have to write Apple to request the ability to download any purchased apps again. The iTunes Store does not recognize that you've already bought an app and allow you to download it again, it only asks if you're sure you want to purchase it again. On the device itself, purchased apps in the Apps Store are badged with an "installed" tag rather than any install option, but still can't be downloaded again.*

To clarify: it does recognize that you've purchased an app before, and it offers a free download when you go to replace a missing app, and I've already had to test this with Crash Kart. Now, whether you can do this multiple times or not is another question, I haven't tried it.

RIM, Symbian, Java, and Qualcomm's BREW all have their own certificate signing programs, which cost more to get started with, are more complicated and expensive to use in signing apps, and frequently involve high testing fees that can in some cases approach $1000 per application submitted. Apple does not charge any additional fees on a per app basis.

Symbian's certificate signing program is optional. It's not mandatory like Apples.

edit: I forgot you can also 'Self sign' your apps - cost zero.