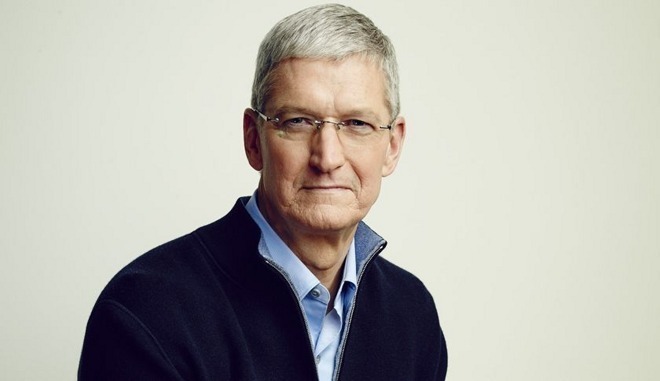

The U.S. Congress should implement comprehensive federal privacy legislation to protect and empower customers against "data brokers," Apple CEO Tim Cook has declared, calling for lawmakers to introduce landmark reforms that fundamentally change the rules by which companies should abide regarding the collection and storage of user data.

Continuing his calls for greater oversight regarding the handling of consumer data, Cook has written an essay to push for changes to privacy legislation in the United States. Cook starts with a call to action by telling the reader, "In 2019, it's time to stand up for the right to privacy — yours, mine, all of ours."

The major data collection efforts of companies like Google and Facebook are highlighted as a continuing issue, with the amassing of "huge user profiles," data breaches, and "the vanishing ability to control our own digital lives" said to be a solvable problem. The essay, published by Time, suggests "realizing technology's potential depends" on fixing the problem.

"That's why I and others are calling on the U.S. Congress to pass comprehensive federal privacy legislation - a landmark package of reforms that protect and empower the consumer," writes the CEO.

Cook references four principles he laid out to a global body of privacy regulators in 2018 that should guide legislation. The principles included the right to have personal data minimized with companies stripping identifying information or avoiding its collection, the right for consumers to know what is being collected and why, the right to see and make changes to personal data, and the right to security.

"But laws alone aren't enough to ensure that individuals can make use of their privacy rights," Cook asserts. "We also need to give people tools that they can use to take action."

Cook goes on to discuss the concept of a "data broker," a company that collects data from a retailer or other firms providing products and services, which are then compiled and sent to another buyer for other uses, usually without the customer's knowledge. For example, this data could be used to further advertising campaigns, or in the more extreme case of Cambridge Analytica, be allegedly used to influence elections by targeting individual voters.

The amount of data compiled by such firms is immense. A 2014 report by the Federal Trade Commission found one broker's database had "information on 1.4 billion consumer transactions and over 700 billion aggregated data elements," while another covered over one trillion dollars in consumer transactions and a third added three billion new records to its databases each month. Considering the age of the report, it is almost certain the level of data acquisition has increased considerably in the interim.

"The trail disappears before you even know there is a trail," suggests Cook. "Right now, all of these secondary markets for your information exist in a shadow economy that's largely unchecked — out of sight of consumers, regulators, and lawmakers."

Comprehensive federal privacy legislation should "shine a light on actors trafficking in your data behind the scenes," and not just to put consumers in control of their data. While some state laws are moving in that direction, Cook notes there is no federal standard version that protects U.S. citizens in the same way.

It is suggested the FTC should "establish a data-broker clearinghouse, requiring all data brokers to register, enabling consumers to track the transactions that have bundled and sold their data from place to place, and giving users the power to delete their data on demand."

"We cannot lose sight of the most important constituency: individuals trying to win back their right to privacy," urges Cook. "Technology has the potential to keep changing the world for the better, but it will never achieve that potential without the full faith and confidence of the people who use it."

The issue of data collection is being looked at by Congress in a number of different ways. In November, a pair of senators on a subcommittee of the Senate Commerce, Science, and Transportation Committee are working on a draft bipartisan bill that could arrive sometime in 2019.

On Wednesday, Senator Marco Rubio announced he was putting forward a bill that would task the FTC with suggesting new rules that Congress could implement, with the potential of the FTC being granted powers to make up and enforce its own rules.

The full essay follows:

In 2019, it's time to stand up for the right to privacy— yours, mine, all of ours. Consumers shouldn't have to tolerate another year of companies irresponsibly amassing huge user profiles, data breaches that seem out of control and the vanishing ability to control our own digital lives.This problem is solvable— it isn't too big, too challenging or too late. Innovation, breakthrough ideas and great features can go hand in hand with user privacy— and they must. Realizing technology's potential depends on it.

That's why I and others are calling on the U.S. Congress to pass comprehensive federal privacy legislation— a landmark package of reforms that protect and empower the consumer. Last year, before a global body of privacy regulators, I laid out four principles that I believe should guide legislation:

First, the right to have personal data minimized. Companies should challenge themselves to strip identifying information from customer data or avoid collecting it in the first place. Second, the right to knowledge— to know what data is being collected and why. Third, the right to access. Companies should make it easy for you to access, correct and delete your personal data. And fourth, the right to data security, without which trust is impossible.

But laws alone aren't enough to ensure that individuals can make use of their privacy rights. We also need to give people tools that they can use to take action. To that end, here's an idea that could make a real difference.

One of the biggest challenges in protecting privacy is that many of the violations are invisible. For example, you might have bought a product from an online retailer— something most of us have done. But what the retailer doesn't tell you is that it then turned around and sold or transferred information about your purchase to a "data broker"— a company that exists purely to collect your information, package it and sell it to yet another buyer.

The trail disappears before you even know there is a trail. Right now, all of these secondary markets for your information exist in a shadow economy that's largely unchecked— out of sight of consumers, regulators and lawmakers.

Let's be clear: you never signed up for that. We think every user should have the chance to say, "Wait a minute. That's my information that you're selling, and I didn't consent."

Meaningful, comprehensive federal privacy legislation should not only aim to put consumers in control of their data, it should also shine a light on actors trafficking in your data behind the scenes. Some state laws are looking to accomplish just that, but right now there is no federal standard protecting Americans from these practices. That's why we believe the Federal Trade Commission should establish a data-broker clearinghouse, requiring all data brokers to register, enabling consumers to track the transactions that have bundled and sold their data from place to place, and giving users the power to delete their data on demand, freely, easily and online, once and for all.

As this debate kicks off, there will be plenty of proposals and competing interests for policymakers to consider. We cannot lose sight of the most important constituency: individuals trying to win back their right to privacy. Technology has the potential to keep changing the world for the better, but it will never achieve that potential without the full faith and confidence of the people who use it.

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

-m.jpg)

Chip Loder

Chip Loder

Wesley Hilliard

Wesley Hilliard

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

26 Comments

I get the sentiment but regulations like this only make barrier to entry that much higher and Google and Facebook that much more powerful. Which is probably why Zuckerberg supports federal regulations. And of course Apple makes the majority of its revenue and profits from selling hardware so it’s easy for Cook to take this stance. But honestly the reason all this data collection exists is mostly because people don’t want to pay money for software/services. If they did, Facebook would be charging users a monthly fee vs being an ad business.

Be careful what you ask for.

Call me cynical, but I have faith that any such legislation will have clauses requiring data collectors to collect even more data and provide it to the government at any time.

That's just the way these politicians work.

There were suggestions in Brussels during the years leading up to it that Apple was against GDPR. Funny how these things move on isnt it.

Meanwhile, how are those new iMacs, Mr Cook?

There’s a big difference between selling ads, and selling your data.

It’s the difference between me using Google, and me never using Facebook. (I do have a VPN, but I shouldn’t need one)

I have my doubts about Google keeping it clean, so I welcome legislation to enforce it. HUGE penalties please for violations.

I think Facebook is rotten to the core.