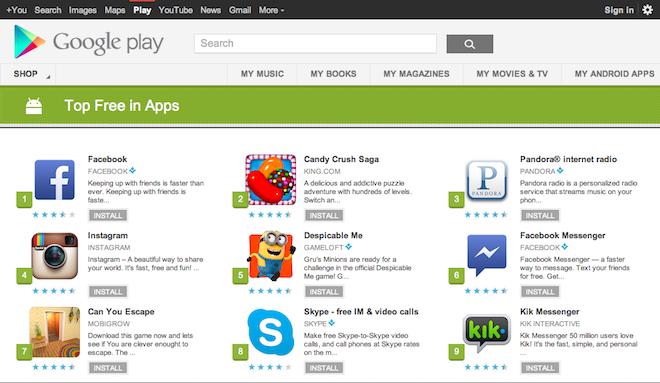

Facebook, the top-ranking free app in Google Play, has taken advantage of Android's weak platform security to collect users' phone numbers as soon as the app is installed, highlighting core differences in Apple's approach to protecting users' privacy and those of social-advertising firms like Facebook and Google.

The news of Facebook's latest "leak" was outed by Symantec after it analyzed various Android apps using its Norton Mobile Insight tool designed to "discover malicious applications, privacy risks, and potentially intrusive behavior."

Symantec didn't need to dig deep into Google Play to find pay dirt, but its researchers still noted that it "even surprised us when we reviewed the most popular applications exhibiting privacy leaks."

The firm stated, "the first time you launch the Facebook application, even before logging in, your phone number will be sent over the Internet to Facebook servers. You do not need to provide your phone number, log in, initiate a specific action, or even need a Facebook account for this to happen.""Unfortunately, the Facebook application is not the only application leaking private data or even the worst" - Symantec

Just one week ago, Facebook users found that it was possible to download private information from people who had "some connection to them," even when that data had not been intentionally shared with Facebook. That illuminated the company's efforts to secretly collect all kinds of data in its social graph to improve its advertising and friend recommendations, beyond the details intentionally shared by members.

Because the various versions of Android have no coherent security policy regarding the sharing of personal data without the user's permission, Facebook's "automatic sharing" in its Android app affects everyone, even iOS users with Android friends.

Symantec said it "reached out" to Facebook, which it said "investigated the issue and will provide a fix in their next Facebook for Android release." Facebook denied that it was collecting the data for actual use and stated that it had deleted the information from its servers.

"Unfortunately, the Facebook application is not the only application leaking private data or even the worst," Symantec noted. "We will continue to post information about risky applications to this blog in the upcoming weeks." In the mean time, the firm recommends that Android users download its tool to see which Android apps are "leaking" private information.

Apple's Walled Garden

Apple's "walled garden" approach to its mobile platform has long erected barriers for app developers, forcing them to request permission before collecting the user's location data, well before anyone anticipated that developers would broadly harvest location data.

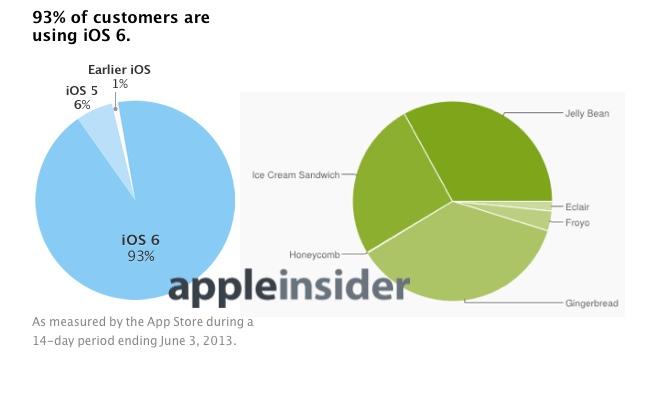

Last year, Apple's iOS 6 similarly began to block unauthorized access to Contacts after Path was found to be unloading users' address books without asking. One year later, 96 percent of iOS users are on the latest version and protected by the security enhancement.

Due to fragmentation on even new Android phones, Google's platform can't be similarly secured even if it were in Google's interests to stop app developers from sharing users' private data for advertising and social recommendation purposes.

Apple's app model on iOS has always blocked third party apps from collecting data from other apps or reading other apps' files that aren't expressly accessed by the user. The company has also worked to protect users' privacy when browsing, turning off injected cookie tracking by default in Safari.

That practice has stymied the efforts of advertising networks to build dynamic Facebook-style dossiers on individuals for ad tracking and behavior purposes, something that bothered Google so much that it simply ignored the security settings to collect data for ads and Google+, eventually resulting in the largest fine in FTC history.

Corporations' end run around Constitutional rights

Recent leaks describing corporate cooperation with government requests for private information have highlighted how businesses that collect large amounts of data for marketing, social graph or other purposes are effectively creating huge repositories for governments to tap into, often with minimal oversight in place to prevent abuses.

Public concerns about the U.S. government's spying programs have reached a fevered pitch so high that Ars recently launched an investigation into whether Apple's iMessage, an encrypted enhancement that provides far more security than plain text SMS messages, could potentially be "spied upon" by Apple itself, something the company has said it simply does not do.

"Apple has always placed a priority on protecting our customers’ personal data" the company had stated earlier, "and we don’t collect or maintain a mountain of personal details about our customers in the first place. There are certain categories of information which we do not provide to law enforcement or any other group because we choose not to retain it."

No comment was made in the article about the complete lack of messaging security on other mobile platforms where SMS messaging isn't encrypted at all, including Android and Windows Mobile.

Encryption does appear to be having an impact on government efforts to police via wiretaps however. A report this week by David Kravets of Wired cited a document by the U.S. Administrative Office of the Courts which noted:"the encryption numbers begin to highlight the government’s stated fear, and its propaganda railing against encryption — which is a standard feature on today’s Apple computers."

"Encryption was reported for 15 wiretaps in 2012 and for 7 wiretaps conducted during previous years. In four of these wiretaps, officials were unable to decipher the plain text of the messages. This is the first time that jurisdictions have reported that encryption prevented officials from obtaining the plain text of the communications since the AO began collecting encryption data in 2001."

Kravets wrote that "the encryption numbers begin to highlight the government’s stated fear, and its propaganda railing against encryption — which is a standard feature on today’s Apple computers."

He also pointed out that "97 percent of the wiretaps issued last year were for 'portable devices' such as mobile phones and pagers," and "about 87 percent of the wiretaps were issued in drug-related cases."

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

-m.jpg)

Bon Adamson

Bon Adamson

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

Wesley Hilliard

Wesley Hilliard

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

-m.jpg)

73 Comments

Pagers? Was this article written in 1993?

MSM: nothing to see here. Move along. We could rag on Facebook, but no one trusts them anyway.

Pot kettle.

This is mostly a non-story in relationship to iOS strengths VS weaknesses compared to Android. iOS has had its own cases of FUBARs in this exact type of thing as well.

The sad state is many applications use various frameworks with minimal testing going on as to what the frameworks do. Many of these are designed for analytics and, if you don't really do your homework, you can get caught with these things. This is not to excuse the behavior but iOS and Android are equally guilty with or without the fragmentation issues.

So how's that open platform thing workin' out for ya?