Shortly after Apple introduced its first custom A4 Application Processor in 2010 to power the original iPad, rumors began to suggest the company could eventually migrate its Macs from Intel x86 processors to ARM chip designs of its own. However, there's a series of significant hurdles the company would need to jump first.

Why today's Macs use Intel chips

Since 2006, Apple's new Mac models have used Intel x86 CPUs, often paired with a dedicated GPU from Nvidia or AMD (or Intel's own basic GPUs used on many entry level models).

Mac software can handle diverse GPU architectures via OpenGL. However, OS X apps and the operating system itself are currently compiled to run on Intel's x86 CPU architecture specifically.

Apple delivered two major versions of OS X (10.4 Tiger and 10.5 Leopard) with software compiled for both PowerPC and Intel CPUs, enabling Macs to run whichever set of code they required. However, since the release of 10.6 Snow Leopard in 2009, Apple has only distributed OS X code for Intel Macs.

It would certainly not be impossible for Apple to deliver OS X in a similar Universal Binary form that could work on either Intel Macs or new Macs using its own ARM processors, but such a move would be an ambitious undertaking involving serious technical hurdles and important market considerations.

How a move to ARM would differ from previous migrations to PowerPC, Intel

Between 1994 and 2005, Apple's Mac OS and software titles generally targeted PowerPC instead, which used CPUs with an entirely different architecture from Intel's x86 chips. Prior to that, the first decade of Macs used four generations of an earlier chip architecture by Motorola called 68k (the 68000, 68020, 60030 and 68040).

Apple's first transition, from 68k to PowerPC, was intended to jump to a new generation of more sophisticated and modern processors designed with the ability to scale upward into 64-bit computing. PowerPC was so much faster than 68k that the new chip could emulate existing 68k code. Many years after the initial transition, PowerPC Macs were still emulating lots of old 68k code.

Apple's second transition, from PowerPC to Intel, was not purely a leap upward. PowerPC chipmakers (IBM and Motorola/Freescale) had essentially abandoned the PC market for embedded roles in automotive and video game consoles because Apple was their last remaining client and fewer than 4 million Macs were being sold every year.

On the other hand, every Windows PC used Intel x86 or a compatible architecture by AMD. Apple's 2006 move from PowerPC to Intel was a leap from a dead platform to a healthy ecosystem where economies of scale were enabling rapid advances in technology.

However, Intel's affordable x86 Core chips were initially 32-bit, a regression from the 64-bit PowerPC processors Macs had been using since 2003's PowerMac G5. Apple had to transition down to Intel's 32-bit Core, then moved back up to 64-bit Intel with the Core 2 family at the end of 2006.

There were also other architectural disadvantages in moving to Intel, but these were greatly overshadowed by Intel's large market and rapid pace of new development. While not dramatically faster than PowerPC from the beginning, Intel's x86 Core chips were fast enough to emulate most PowerPC code reasonably well via the Rosetta technology Apple acquired and further developed to smooth its Intel transition. The move to Intel's x86 architecture meant that Macs could now natively run Windows

Additionally, the move to Intel's x86 architecture meant that Macs could now natively run Windows (or Linux, or other x86 operating systems). Back in 2006, this dramatically broadened the market for Macs, enabling many new users who had a specific need to run certain Windows apps to consider buying a Mac.

Apple's Boot Camp allows booting Windows directly from a drive, while third party software can run Windows hosted within a window on the Mac desktop. Both options are far faster than emulating Windows' x86 code on PowerPC, the only option Mac users had before the move to Intel chips.

Why Apple might consider replacing Intel chips

The primary reason for Apple to consider developing Macs using a non-Intel processor is cost. Intel makes its money developing advanced processors that are hard to copy or compete against, so it can charge prices padded with a steep profit margin.

While it's hard to determine exactly how much Apple pays Intel for its chips, or how much it costs Apple to develop and manufacture its own ARM Architecture designs, IHS iSuppli estimates that the Intel Core i5 used in Microsoft's Surface Pro costs "4 to 5 times" the ARM chip used in the Surface RT, contributing towards a bill of materials $180 higher and a retail price premium of $300 (note that the CPU is not the only difference).

The same firm generates reports (again, of unknown accuracy) that suggest that A6 chips cost Apple around $25 per iPad, but that it pays Intel somewhere around $180-300 for the Intel chips that power Macs. The tantalizing idea of Apple replacing $200 Intel processors with one or two of its own $25 chips is the primary fuel powering the Mac/ARM rumors.

However, those two examples compare very different chips; today's ARM tablet chips are far less powerful than even entry level Intel Core i5 processors. Microsoft's failed experiment in porting Windows to ARM for the Surface RT highlights the vast computing power difference between modern Intel processors and the fastest ARM chips.

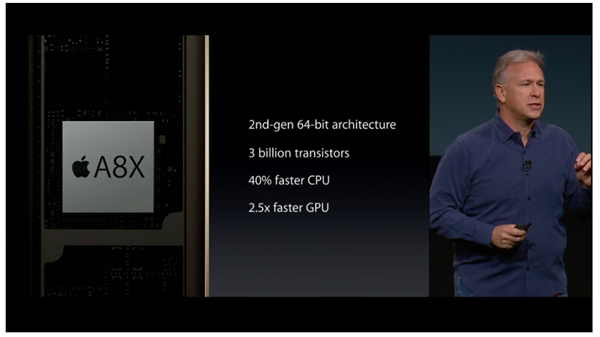

Second: Apple could design much faster ARM chips, if it wanted to. Apple has been aggressively ramping up the sophistication and processing power of its Ax-series processors, financed by the tremendous economies of scale it achieves in selling nearly 70 million iPads and almost 170 million iPhones every year.

This year, Apple could have made even faster A8 chips, if it were not constrained by the thin form factors, limited battery size and thermal envelope of its iOS devices. The company made it clear that energy efficiency was a primary design goal for the A8X, in order to enable it to power the thin iPad Air 2 using an even smaller battery than before, without giving up battery life or performance.

In a Mac mini or even a MacBook Air, Apple would have far fewer constraints on power consumption and heat dissipation, allowing it to clock its chips faster and design them with more cores and other specialized logic hardware and equip them with more RAM and larger caches.

All things considered, were Apple indeed interested in moving even a specific new Mac product (such as the oft-rumored "low cost" MacBook Air) to a custom new ARM chip, it certainly isn't far away from being able to match Intel's low end desktop processors at an attractive price. ARM is already beating Intel's mobile x86 Atom chips.

Before Apple moved to Intel chips, it was building around 4 million Macs per year. This year, it is building nearly 20 million Macs per year, roughly as many as the number of iPads Apple sold over its first four quarters. Apple considered Intel's x86 Atom chips when designing iPad, but decided to go with ARM instead (and that was before Apple expected to sell 20 million iPads in its first year).

That suggests the volume of Macs now being sold is at least in the range of what could be considered feasible to sustain a non-Intel architecture, resulting in the potential for substantial cost savings.

Third: Apple might want to own the core silicon technology in Macs. As it has done with its custom ARM chips for iOS products, Apple might have compelling reasons to optimize its processors to run OS X, eliminating any general purpose logic that Apple doesn't use and adding custom silicon to provide differentiated, hardware-accelerated features such as fast encryption, audio processing or video encoding.

Getting Macs and iOS devices on the same chip architecture would potentially allow easier cross pollination of such hardware technologies, just as having a very similar OS and APIs allows Apple to share software-level technologies between its iOS mobile devices and Mac computers. If Apple were to leave Intel's x86 for its own, custom ARM architecture in Macs, it would have a much greater impact on Intel than is apparent in comparing the actual units involved

Further, by developing advanced proprietary technology that is only available in its own Ax chips, all the investments Apples makes would only benefit the company itself. Currently, the profits Apple pays to Intel for its Mac processors indirectly benefit the rest of the PC industry, because they enable Intel to build better chips that everyone else can use, too, with cost savings from the economies of scale that Apple's volumes generate.

If Apple were to leave Intel's x86 for its own, custom ARM architecture in Macs, it would have a much greater impact on Intel than is apparent in comparing the actual units involved: roughly 20 million Mac units would disappear from the roughly 300 million PCs sold in total. Not all of those PCs bear Intel chips, but Apple's Macs have cornered the premium PC market for Intel chips, and represent a huge proportion of total PC profits, globally.

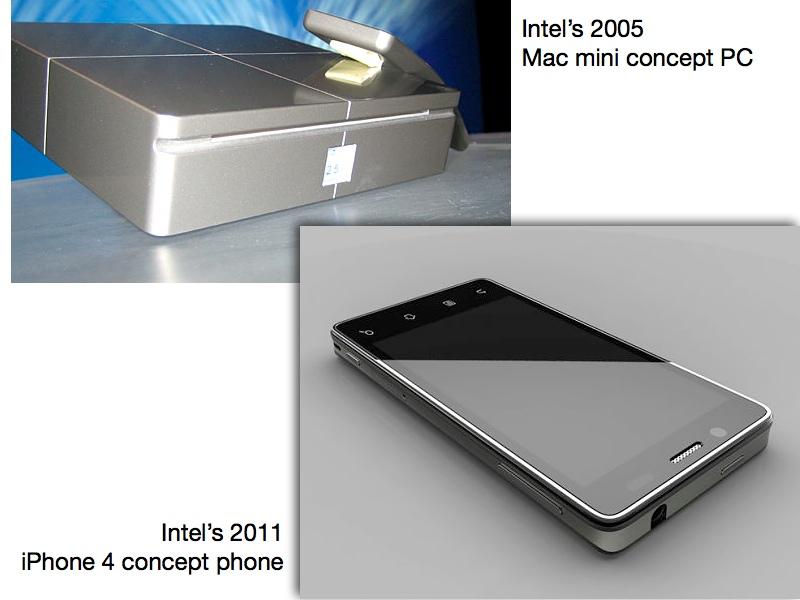

Without Apple, the Intel PC market would see its Average Selling Prices plummet. Given how poorly Intel has performed in getting PC makers to build Ultrabooks, Mac mini clones and Android Atom tablets (let alone its failure to participate in the smartphone market at all, despite its efforts to get PC makers to clone Apple's designs), the loss of Intel Macs would be nothing short of disastrous for Intel and everyone else who uses x86 chips.

Why Apple might not want to replace Intel chips

Apple originally moved to Intel for good reasons. In 2006 Apple didn't have any significant in-house chip design team and it didn't have vast capital to go out and develop its own chip technology. Leveraging the work Intel had already done— and had available to sell— not only made sense, but was by far the best of the very few options available to Apple at the time.

While Apple is now one of the world's leading mobile chip design firms and has $150 billion in cash to embark upon ambitious new projects, remaining a customer of Intel still makes sense for a number of reasons.

First, Intel currently offers world-leading chip technology and fab production capabilities that Apple can afford. By remaining an Intel client, Apple's Macs can inherit the broad and deep engineering work Intel has invested to serve the world's PC needs, and benefit from all of the future investments Intel will be making to remain the world's most advanced PC chip maker.

Apple has to pay the Intel premium for this technology, but of all PC makers worldwide Apple has the most capital to afford it. Further, Apple's profitability and relative scale (it's not a volume-leading Intel PC maker, but is within the top five) enables it to enjoy priority chip selection and volume discounts. Apple's Mac margins remain relatively astronomical among PC makers, despite paying Intel for its chips.

Historically, while Apple doesn't waste money frivolously it does not appear to have a problem in paying a premium to gain access to superior technology. Apple buys the best display panels it can source, it paid a premium to acquire AuthenTec, and it licensed the real Helvetica. Microsoft and Google are notorious for accepting low quality displays, both passed on the idea of expensive fingerprint scanners and both sourced second-rate knockoff versions of Helvetica: Arial for Windows and Roboto for Android.

Second, moving to ARM would eliminate AMD as a potential x86 supplier. Migrating away from Intel would eliminate a second potential supplier option that Apple hasn't yet exercised: AMD's compatible x86 chips.

Apple already buys Mac GPUs from both AMD (which acquired ATI) and Nvidia, switching back and forth as each releases new technology or offers better prices. Apple can do that thanks to OpenGL, which makes moving between the two GPU vendors easier.

Apple hasn't made any effort to play AMD against Intel in the x86 CPU market, but it potentially could were Intel to drop the ball and if AMD launched some significantly superior, less expensive chips for running x86 code in Macs. Moving Macs from Intel to ARM would erase Apple's option to more cheaply and effortlessly move from Intel to AMD.

Third, a partial move to ARM might not save Apple much money at all. Nobody believes Apple currently has the ability to realistically replace Intel chips across its entire Mac lineup, particularly on the high end with Mac Pros and MacBook Pros, where Apple makes much of its profits and retains a loyal customer base with little real outside competition.

Even if Apple were to only produce a single new model of ARM-based Macs, it would reduce its bargaining clout with Intel for the remaining x86 chips it needs to buy, potentially increasing its costs to the point where it wouldn't be saving any money on its partial move to ARM.

Just because something can be done doesn't mean it will work out well, even if there appears to be very good reasons supporting the effort. Microsoft's porting Windows to ARM didn't attract any real new business, didn't result in a product the market found superior to other alternatives, harmed Microsoft's relationship with Intel and consumed two years of work at Microsoft that potentially could have been applied to more fruitful efforts.

Intel reacted by announcing (even if ultimately ineffectually) support for Google's Android and Meego/Tizen. It spent billions subsidizing tablet makers' use of Atom, a move that directly targeted the same demographic that Microsoft expected to consider buying its Surface RT.

Parts of Microsoft's Windows RT for ARM may be salvageable for use in other efforts, but it was clearly not successful in saving Microsoft and its PC makers money. Of course, money savings was not Microsoft's primary goal; the project aimed to leverage the superior energy efficiency of ARM chips over Intel's desktop x86 or mobile x86 Atom alternatives. But that advantage was undermined by the reality that existing Windows apps couldn't work on ARM hardware.

Surface RT wasn't Microsoft's first commercial failure related to porting Windows. It had previously tried to port Windows NT from Intel x86 to a variety of alternative chip architectures in the late 1990s (it briefly ran on MIPS, the DEC Alpha and PowerPC), and also ported its mobile Windows CE to work across a variety of mobile chip architectures (including x86, MIPS, SuperH and ARM).

That diversity primarily just increased costs and complications, and was eventually abandoned to standardize upon x86 Windows PCs (in 2000) and ARM Windows Phones (in 2010).

Apple (along with NeXT) has a long history of successfully porting software to new architectures. However, despite its proven ability to support diverse hardware the company has generally worked to finish transitions quickly and migrate its installed base to a single standard to avoid the hardware fragmentation problems apparent on platforms such as Android.

Fourth, developing a Mac-class ARM chip would incur significant risk. In addition to direct costs, such a move would also involve an expensive opportunity cost: the distractions and complications that might slow development of Apple's mobile chips targeting iPhones, iPads and other new products.

Apple sold over 244 million iOS devices in the last fiscal year, compared to "just" 18.9 million Macs. Mobile devices also make up the majority of Apple's revenues and profits. Prioritizing a risky Mac transition over the advancement of its bread and butter could allow other mobile device makers to catch up faster than if Apple were to focus its efforts where it makes its money.

Unless Apple has tons of engineers just sitting around with free time to solve new problems, it doesn't seem like it would make sense to spread its chip design team so thinly across both its highly mobile iOS devices and the completely different designs required by conventional Macs, unless there were a tremendous benefit in the short term. Beyond alienating a key supplier, Apple would also risk confusing its own customers and tarnishing its brand

Beyond alienating a key supplier, Apple would also risk confusing its own customers and tarnishing its brand. Microsoft certainly lost credibility with customers when it launched Surface RT, a product that portrayed itself as an "uncompromising" Windows computer, without actually being able to run Windows software and with severe design compromises related to the limited horsepower of its ARM chip. Mac buyers have even higher expectations for new Macs.

Fifth, ARM incompatibility with x86 would require significant first and third party adaptation. Apple has significant experience in porting its own OS, frameworks, apps and development tools to new hardware architectures. It moved Mac OS from 68k to PowerPC, then ported NeXT software from Intel to PowerPC to deliver OS X, when it then ported back to Intel. iOS is essentially OS X ported to ARM, with significant optimizations for mobility.

Apple certainly knows how to deliver an ARM version of OS X and it would be relatively straightforward to build the tools to help developers recompile their Mac apps for ARM. However, it would still be a lot of work, and would require significant effort from developers.

The costs (and opportunity costs) involved with creating new Mac/ARM app ports and a converted ecosystem might outweigh the value in doing so, particularly if Apple continues to sell fewer than 20 million Macs in total.

Apple TV a case study in migrating to ARM

In addition to Microsoft's Surface RT, Apple TV provides a second recent example of processor migration. The original Apple TV sold between 2007 and 2010 was essentially a scaled down Mac, running a modified OS X on an Intel x86 processor and Nvidia CPU.

In late 2010, Apple released a "second generation" successor running a version of iOS on its own A4 processor (incorporating the same GPU cores iOS devices use). That shift (involving a complete hardware architecture overhaul) helped Apple to drop the price from $299 to $99.

Apple TV is certainly a special example. The company long regarded it as a "hobby" and continues to sell it as a strategic product rather than seeking to make it a profit center. Its margins are very thin, it still sells in relatively small volumes and it doesn't run third party apps.

Migrating Apple TV to iOS and ARM was essentially a no-brainer. There was essentially no real market for a $300 TV box, while at $99 Apple TV turned into a billion dollar annual business (including the media it helped to sell). By 2010, Apple had a source of unusable A4 (and later A5) chips unfit for iPads that it could essentially recycle as Apple TV boxes. It was an ideal candidate for ARM migration.

ARM MacBooks an unlikely move for Apple in the short term

Turning to conventional Macs, the question of moving to ARM isn't about whether it's possible for Apple to replace Intel, but rather whether it makes sense commercially and if it's the best thing Apple could be spending its time and resources to accomplish.

If Apple were indeed trying to deliver a netbook-like MacBook Air that could be sold very cheaply, it would make lots of sense to dump Intel's expensive Core i5 chips and build a low cost iOS or scaled down Mac/ARM product. That's very similar to what Microsoft did with Surface RT, and could also be compared to the ARM-based Chromebook products being sold by HP and Samsung (powered by Samsung's Exynos ARM chips).

However, there's little compelling evidence that Apple is imminently interested in selling cheap, low power notebooks. It is currently selling record numbers of Macs at its existing price points ($900-$3000), and it already has iPad to serve as a lower price computing product in the $200-$800 range.

While Apple's FY 2014 iPad sales were down slightly (4 percent) from the previous year, it's not as if iPad sales are "collapsing" and in need of a replacement form factor. In reality, it appears that Apple has upgraded potential iPad sales into full blown Mac buyers, a much more lucrative achievement compared to turning Mac users into iPad customers.

The negative reviews and user disappointment achieved by low powered but cheap netbooks including Microsoft's Surface and Chromebooks from HP and Samsung are not exactly what Apple has ever aspired to accomplish.

However, the tech industry is always changing and frequently disrupted by new products that cost less while doing less. Apple's iPhone, iPad and Apple TV are all examples of new products that sold for considerably less than the "smartphones," tablets and set top boxes that preceded them, often bearing "features" that Apple eliminated to invent an attractive, affordable new product category.

ARM-based Macs, other the other hand, would largely disrupt Apple's own premium Mac business. Conceptually, Apple could create a low cost MacBook/ARM specifically targeted to, say, education, but that's a very small market, and one where Google is currently dumping Chromebooks at cost.

A year or two from now, circumstances might change. Apple might reach the point where it finds it hard to expand its premium Mac business further. The company could develop technology that enables its ARM processor designs to aggressively move into Intel's performance range at a much lower cost.

Apple could develop hardware support for rapidly emulating x86 code on ARM, minimizing the transition costs and making it easier to rapidly migrate to ARM.

Intel could fail to deliver new breakthroughs for x86, making it more attractive for Apple invest in the development its own advanced ARM processors (or even an entirely new chip architecture) for desktop and notebook computing.

Overall, however, it appears that the conventional desktop and notebook PC market has reached a plateau. Within the finite market for PCs, Apple has been expanding its share of premium PCs now for several years, and it appears able to continue eating up rival's higher end sales without making radical changes.

Instead, it appears that there are better ways for Apple to spend its vast but finite resources rather than working to displace Intel as a supplier for a few million Mac models, at least within the next few years.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

-m.jpg)

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

Andrew O'Hara

Andrew O'Hara

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

-m.jpg)

102 Comments

A very interesting article. I'd throw in a few points here ... Not just CPUs but also Apple GPUs from Apple is key for me. Apple getting away from third party GPU vendors would (hopefully) remove one of Apple's worst Achilles heels. The cost of Intel chips would have to increase if Apple stopped or reduced using them I would think and help kill the remaining Wintel Boxes. That or Intel is doomed even sooner. Plus Intel would cease getting help from Apple in design. Apple have always managed to create a method of running legacy applications for a few iterations of a new CPU adoption to give software makers time to transfer. Apple have always provided migration help for those developers. IMHO a move is likely down the road for the reasons given in the article and all the negatives can be overcome even if it takes several years and only certain Macs go first. Lastly there is no reason Apple would make any Mac a 'cheap' Mac just because they save on the CPU costs. Apple could and should always maintain high end pricing but offer a hell of a bang for the buck in terms of quality and bleeding edge technology. No one is surely suggesting an A10 (or whatever CPU) in a MBA could make, would be a Netbook are they? Oh I nearly forgot ... and who the hell needs to run Windows these days anyway ..? ;)

Excellent story and analysis! :) The last thing I look forward to is yet another hardware transition, but if the benefits are there and we finally get true cross platform software I wouldn't mind. The question that immediately cam to mind is: Has anybody had a shot at getting the Apple TV to do anything else? It bears a resemblance to the Raspberry and other similar small scale boards with the added advantage of being ready to run with its own case, power supply and ports. Imagine if it ran iOS on a large touch screen. It certainly would meet a lot of computing needs and also be an excellent Kiosk. It could even cut an entirely new form factor, or variant on the iMac just by integrating it in a display.

The second problem is no longer really a problem, as AMD has ARM chips, both in market and in the pipeline.

True full x86 compatibility is a must. And that means Intel. Full stop.

@digitalclips I know you're being funny, but plenty of people still have to run Windows, unfortunately. Excel doesn't even compare between the platforms, and seems the Mac version can not keep up in a business environment. 3D Studio Max is still a large standard, and has yet to make its way to the Mac platform (Autodesk, get off your ass!).

I tend to agree with the article. I think ARM is a ways off. I think the AMD option argument is the most interesting of all. If price truly is the defining factor, Apple could help fund AMD to get back on track and use that as a bargaining chip against Intel.

My fear is that Intel has dropped the ball the last year, they missed their Broadwell ship time and just seem to be off lately. A sign that was quite similar to the way IBM was handling PPC towards the end of that era. I think the mobile market caught Intel off guard.

At a minimum, we have common developer tools to compile for both ARM and Intel. I don't think the transition would be much, if at all, assuming the app is on a modern codebase. Swift being released could also point to a transition path as well, though some years off which may align with an ARM transition.

Personally, I'm not a fan of it at all. I'm quite happy with Intel as a power user, and wish Intel would work something out so Apple and them could co-design mobile cpus that are both powerful and energy efficient. Intel has a lot of great minds, they need to figure something out, soon.