Apple was on the list of attendees at a secretive three-day conference last week, where heads of intelligence agencies from around the world met with private sector tech companies, security experts and journalists to discuss the ramifications of data privacy on state protection.

According to The Intercept, which obtained a copy of the event program, the summit was chaired by former British MI6 Sir John Scarlett as part of an ongoing series of conferences put on by the Ditchley Foundation. Said to discuss "complex issues of international concern," these highly confidential meetings are held at the foundation's mansion in Oxfordshire.

The guest list reads like a who's who of current and former high ranking government surveillance officials from the CIA, British signal intelligence group GCHQ, German intelligence service and many other agencies from the U.S., Australia, Canada and the EU. Apple's director of global privacy Jane Horvath and security and privacy manager Erik Neuenschwander represented the company's interests, while executives from Google and Vodafone were also in attendance.

Also present was current GCHQ chief Robert Hannigan, who recently condemned U.S. tech companies like Apple and Google as "command-and-control networks of choice for terrorists and criminals." Hannigan's stance mirrors that of his counterparts in the U.S. intelligence community who argue that access to public data is vital to national security.

Data privacy has been a hot button topic since former NSA contractor Edward Snowden leaked classified information regarding secret government surveillance programs that collect data on a massive scale. In question are collection techniques that ingest data wholesale, with everything from phone calls to social network posts scrutinized without the user's knowledge or proof of wrongdoing.

Law enforcement agencies argue that a certain level of access to private data is needed to adequately conduct criminal investigations. Specifically, justice officials sometimes request personal data logs from telephone companies, cloud service providers like Apple and other entities in a lawful procedure allowed through court-ordered warrants.

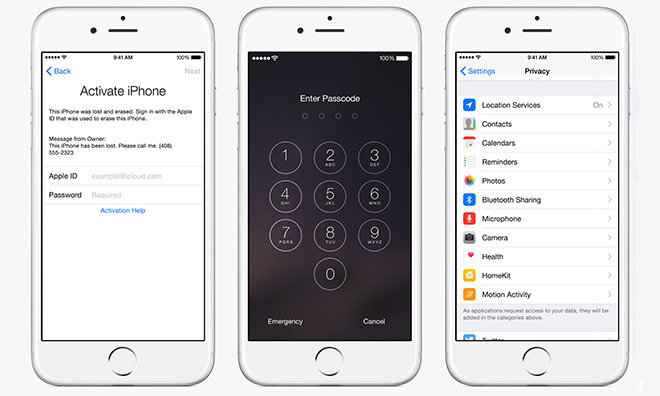

Amid the Snowden leaks, technology companies began to provide consumers with communications products that boasted advanced encryption features. Apple was one of the first big tech firms to offer consumers high-security encryption in iOS 8, claiming at the time that its system was so secure that user data would be inaccessible even with the appropriate documentation.

While Apple's efforts are not designed to expressly thwart government sanctioned snooping, CEO Tim Cook has been an outspoken advocate of consumer data privacy with a hardline stance against data sharing.

"None of us should accept that the government or a company or anybody should have access to all of our private information," Cook said during an interview in February. "This is a basic human right. We all have a right to privacy. We shouldn't give it up. We shouldn't give in to scare-mongering or to people who fundamentally don't understand the details."

Law enforcement agencies, however, find Apple's technology, as well as similar efforts from Google, counterproductive and even detrimental to time critical criminal investigations. In the U.S., some officials are pushing policy to institute mandated software backdoors for crime fighting purposes, but private companies that have an interest in keeping buyers happy are showing resistance. Most recently, Apple and other tech companies signed a letter asking President Barack Obama to disregard such measures, arguing that strong encryption is necessary to secure the "modern information economy."

The issue, then, becomes one of striking a balance between public privacy and lawful data access, a problem supposedly addressed during last week's summit. The Intercept notes the Ditchley conference is evidence that government and private companies are showing an increased willingness to discuss the matter, at least behind closed doors.

Mikey Campbell

Mikey Campbell

-m.jpg)

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

Chip Loder

Chip Loder

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

-m.jpg)

15 Comments

So... completely absent and left unrepresented in these secret meetings are the very citizens affected by these outrageous abuses of power.

So... completely absent and left unrepresented in these secret meetings are the very citizens affected by these outrageous abuses of power.

Too true !! Where are those representing us, me and you, the users. Even a cursory read of some of the stuff that Snowden has released would have us all really worried. (For once Spam you have something useful to contribute rather than your usual banal rubbish!)

> striking a balance between public privacy and lawful data access I can't see that existing. Even the smallest back door will eventually make it into the public domain for all to abuse.

"Don't hate the players (Apple, Google)... Hate the game!" --Chris Rock

The judiciary in the US has weighed in against the spy agencies... the second circuit court of appeals has deemed mass collection of data is illegal...so the spy agencies are on dubious legal terrority.