Last week, developer Marco Arment suggested in a blog posting that if Apple were to fail to grasp the potential for voice-based Artificial Intelligence to change the nature of smartphone demand, the company's core revenue generator could suffer the same fate as RIM's Blackberry, which a decade prior had similarly failed to see the importance of iPhone's advanced multitouch experience until it was too late to do anything about it.

Before the iPhone, Samsung had to copy RIM's Blackberry

Arment's think piece described Blackberry (which a decade ago was known as RIM) as the "king of smartphones" prior to the iPhone's introduction in 2007, writing that "they were the best and most successful at what most smartphones were for at the time: email and phone calls."

He then posited that "today, Amazon, Facebook, and Google are placing large bets on advanced AI, ubiquitous assistants, and voice interfaces, hoping that these will become the next thing that our devices are for. If they're right — and that's a big 'if' — I'm worried for Apple."If Carson had put some thought into critically examining what Arment wrote, she might have realized how fragile the entire idea actually was

He added "... if Google's right, there's no quick fix. It won't be enough to buy Siri's creators again or partner with Yelp for another few years."

There are some core problems with piece, but the biggest one is that Biz Carson of Business Insider latched onto it to drive a fear mongering amplification for her own clickbait audience.

If Carson had put some thought into critically examining what Arment wrote, she might have realized how fragile the entire idea actually was. Instead, she just replicated it for her own audience next to her site's own ads (a sort of Google Verbatim Appropriation, you might say).

Peak iPhone Panic

Stories of panic that paint a credible path to Apple's rapid demise have always been popular as link-bait, but today the attraction is simply off the charts, due to the fact that the Internet has shifted from an alternative way for print and television journalists to distribute their ideas into an ad-supported trough where the dumbest ideas which can generate the most outrage best serve as co-conduits for paid messages.

Welcome to Google's ad internet, where the New Content is ads and the headlines are just tricking you into reading them! This problem is tightly bound to another problem: a complete ignorance of why Apple, not Google, is generating so much free cash flow and how Apple ever got to its current position when everyone knows, via Google's ad supported news channels, that Android is winning!

Fortunately both ideas are so tightly bound together that they can be dissected in one article.

Peak iPhone? The consumption of computers is not over

There appears to be a broad consensus among pundits that iPhone growth is going away, and that without selling increasing volumes of iPhones each quarter— and without Steve Jobs to invent some new product category— Apple will be unable to maintain its position as the world's largest and most valuable tech company.Once you begin taking a closer look at the history of Apple and RIM, the surface comparison begins to implode under the weight of facts

The idea that Apple could become a Blackberry is therefore a provocatively attractive one. However, once you begin taking a closer look at the history of Apple and RIM, the surface comparison begins to implode under the weight of facts.

First, take a look at where Apple was prior to the iPhone. Coincidentally, criticism of Apple back then was shockingly similar to where it is again today. One might say this all happened before.

Remember Peak iPod?

A year or two prior the point of Peak iPod— which in retrospect we know actually occured in 2008, based on unit sales figures— the storyline of Apple's impending demise began to orbit around how poorly positioned the company was because in comparison to iPods its Mac business almost didn't matter anymore (iPods were outselling Macs by 10x), and the core value of iPods at the time was centered on their ability to play MP3s, a feature that an emerging number of smartphones (and even feature phones) had already begun to deliver.

Apple is going to be stuck trying to sell iPods to a market already satisfied with their MP3-playing phones, pundits claimed in near perfect unison. Additionally, they claimed that Apple had no ability to enter the phone business because the market already had many experienced, entrenched players who were much larger than Apple and would offer fierce competition to any new upstart trying to muscle into their territory.

In hindsight, and equipped with our knowledge of how remarkably well Apple entered and then mastered the phone business, the idea that Apple would remain wedded to the past and fail to translate its past success into the future seems so wrong that it's almost hard to believe that anyone ever thought that.

Apple had previously made a series of transitions that were virtually unprecedented in the industry. It had switched the Mac's chip architecture twice already, once to PowerPC and then to Intel. It had also shifted its Mac platform OS from an embedded System Software to a "modern" Unix based OS using advanced developer frameworks and a futuristic vector graphics compositing engine.

And in iPods, it had also transitioned from high end hard-drive based designs to new generations of solid state flash storage, deftly conquering new segments of the market. And while doing that, it fended off competitive threats from much larger companies, ranging from the Walkman-originator Sony to Microsoft and its Windows Media Player licensees, which were almost universally expected to gobble up Apple's iPod sales via commodity devices.

Apple should have earned at least a little benefit of the doubt. Today however, that's even more true.

VR, AI and Peak iPhone

Yet virtually the exact same scenario is playing out today, where we are increasingly told that "everyone who wants an iPhone already has one," (even though that is obviously false) and that the future will be delivered by companies who are working on Virtual Reality and/or Artificial Intelligence concepts in public view, companies that have already shown some initial prototypes and even delivered consumer products fit for early adopters.In 2006, there were a broad array of profitable smartphone makers; building smartphones was considered to basically be picking money off trees. Today, most of the smartphone makers are losing money

Those same companies also previously introduced NFC payments, fingerprint scanners, music subscriptions, voice services and a variety of other concepts years in advance of Apple, without actually holding on to their lead once Apple began competing in those same fields. In part, that's because Apple worked on its own solutions in private, and delivered them once they were ready.

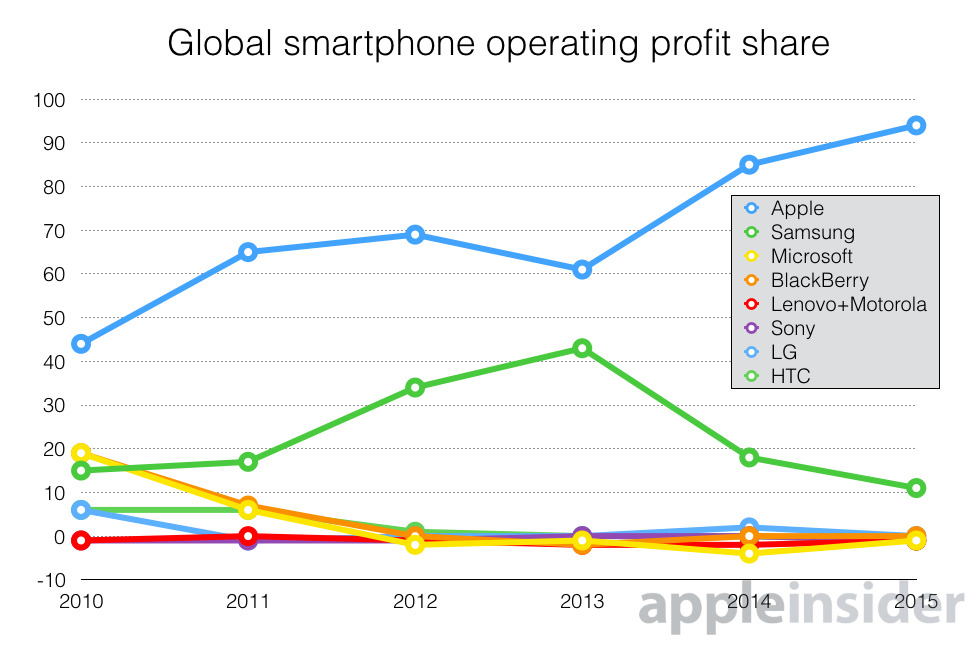

There are some other key differences between today and decade ago. This time around, Apple is bigger and more powerful than every other company in the industry, even while it remains unique in its ability to make money (in PCs, phones, tablets, smartwatches, Apple sells virtually all of the products that are actually profitable).

In 2006, there were a broad array of profitable smartphone makers; building smartphones was considered to basically be picking money off trees. Today, most of the smartphone makers are losing money.

Apple doesn't look like Blackberry at all

Also, the product that is now supposedly going to turn Apple into a Blackberry is not an existing device that virtually everyone already owns but which Apple does not make (a 2006 mobile phone), but rather an application of the device that everyone owns and which Apple already makes.

Apple's iPhone overwhelmingly dominates premium smartphone sales. No previous competing feature has ever threatened that, despite many being clearly valuable (such as having support for LTE mobile networks, a feature Apple belatedly joined years after its rivals). A key reason is Apple's vast scale.

When Apple launches a new iPhone, it now sells about 70 million during its launch quarter (most of those are the newest model; all of them are premium smartphones). When Apple's next largest competitor launches a new Galaxy S, it ships out 10 million or fewer in the launch quarter, along with a huge volume of devices that are not premium smartphones capable of demanding a significant profit.

Samsung's premium smartphone sales peaked a few years ago and its IM Mobile profits haven't recovered since. Samsung has experienced two years' worth of quarters where profits haven't come close to what they once were at Peak Galaxy, a fact that nobody likes to talk about (because why kick a company when its down?).Even with a temporary drop in quarterly sales, Apple still makes more money than the rest of the smartphone industry combined. That's an important detail

Apple has had one quarter that was down from its year-ago surge related to the mega-launch of iPhone 6. It's currently impossible to write about Apple without noting that Apple's Q1 sales (and perhaps its next quarter of sales) were down, the first time this has happened since something like 2003.

But it's okay to kick Apple because it's not really down. Even with a temporary drop in quarterly sales, Apple still makes more money than the rest of the smartphone industry combined. That's an important detail.

Apple's sales would have to collapse by about 75 percent for Apple to even be at the level of Samsung. A few years ago, Samsung Mobile shipped twice as many phones as Apple but made about the same amount of money. Today it sells about half again as many more, but brings in profits that are a quarter of Apple's.

Apple is not in a downward spiral. Comparing Apple with its current competition and looking for ways Apple could be outmaneuvered requires some seriously naive leaps of logic, simply because Apple is not just larger, but also far better managed, focused and competent at delivering its objectives.

Five years of iPhone

That's a radically different competitive environment from 2006. Back then, Apple's annual profits were $2.4 billion, and the company was valued at around $60 billion, roughly equal to Dell. Blackberry maker RIM was valued at $16 billion, almost seven times [correction: just over a third] more than Apple.In 2006, Blackberry maker RIM was valued at $16 billion, almost seven times more than Apple. It wasn't because Blackberry had the best phones or was the "king of smartphones."

Blackberry didn't have the best phones nor was it the "king of smartphones." Blackberry's devices were also not "the best and most successful at what most smartphones were for at the time."

What the company uniquely had was the Blackberry Enterprise Server (BES), a proprietary messaging infrastructure that made its devices very sticky to enterprise customers. That's where most of the company's profits came from.

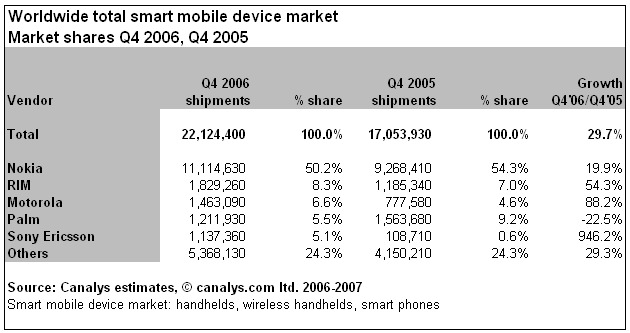

RIM's share of the 2006 smartphone market was just 8.3 percent, not all much larger than Motorola or Palm.

Today, Apple sells nearly twice as many iPhones per quarter in its slowest quarter than all smartphone vendors combined did back in 2006. Apple didn't just convert RIM users to iPhone users; it dramatically expanded the smartphone market by making iPhones attractive to vast new audiences.

Source: Canalys

Source: CanalysThe real king of smartphones was Nokia, with a market cap of $100 billion— nearly as big as Google at $120 billion. Microsoft (whose share of smartphones was scattered among its licensees) was valued at almost $240 billion. Looking at those numbers, it's not extremely hard to understand why nobody expected Apple to replicate its iPod magic in phones, given the size of its rivals.

Apple's primary apparent competition was not really Blackberry, but rather Nokia's Symbian and Microsoft's Windows Phone platform— which was benefitting from its connection to the successful Windows PC platform (and a recent deal that had converted about half of Palm's users to Windows Mobile-powered Palm smartphones).

Five years later, after the launch of iPhone and iPad, Apple's profits had ballooned to more than $16 billion annually, and its market valuation had soared to $323 billion. RIM's valuation had only grown slightly, to less than $26 billion.

It's not hard to understand how the once-important Blackberry failed to replicate Apple's iOS when it finally woke up years later and began assembling the components of its own QNX-based BB10 starting in 2010. By that time, it was less than a tenth Apple's size, and it had wasted four years in me-too surface competition.

The companies investing in AI today are not ten times bigger than Apple, and they haven't successfully deployed a universally attractive new product that Apple has ignored for the last four years.

Apple's iPhone disrupted RIM's BES

Additionally, Apple didn't disrupt RIM by launching an iPhone with apps. Blackberry had apps. RIM didn't fail to recognize the importance of a third party app store.

Blackberry OS had been a Java Mobile platform, similar in some respects to Nokia's Symbian. Windows Mobile had apps. Palm OS had apps. All of those platforms could run Java apps. Apple didn't invent the idea of a smartphone and outsmart companies who didn't see the value of running third party software. Apple was actually late to that party.

But when Apple did arrive, it brought a vastly more powerful operating system, more powerful development frameworks and more powerful hardware to run them, delivered as the premium-priced iPhone. Blackberry, Nokia and Microsoft literally laughed off Apple's approach, until they belatedly realized it was working.

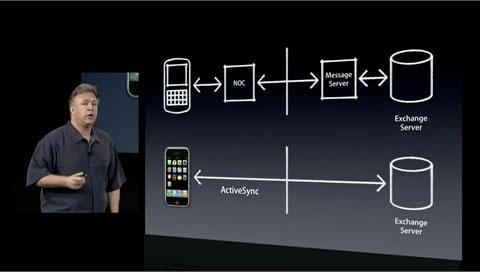

What Apple did do is target where RIM was making its money: BES. It did this by partnering with Microsoft to deliver ActiveSync push messaging, along with its own push notifications and MobileMe (remember that huge failure that pundits like to mock?) to erase the value BES was providing to Blackberry users.

That factual context is lethal to the idea that Apple is fated to experience Blackberry's demise if it fails to join Google in talking about its plans for AI. Apple didn't just introduce a new way to interact with smartphones. It radically revolutionized how phones were sold, who was in control of the user experience, and how money could be made in the industry. That's something its competitors, including Blackberry, failed to grasp soon enough back then, and it's something Apple's smartphone rivals still haven't matched.

The Apple of 2010

Across those same five years of iPhone (and iPad) that earned Apple a market cap of $323 billion, Google's valuation had only grown to $172 billion, and Microsoft had actually fallen backward to just below $220 billion. Nokia, once the leader of smartphones globally, had collapsed to just above $30 billion.

Apple's development of iOS, and its successful deployment of it on a phone and a tablet, wasn't just a successful event. It radically changed the playing field. The much smaller Blackberry failed to similarly radically turn the industry around, and even Microsoft completely bungled two attempts to match the iPhone and iPad: first in porting its own Windows to ARM to battle the iPad with Surface RT, and secondly to establish Windows Phone as a contender on phones.

The ability for a new company to break into phones and radically change the landscape (and steal away a significant portion of Apple's premium market) was even by 2011 an exponentially more difficult leap than Apple's own play in turning its advanced OS X development tools and the iPod's high volume premium hardware business into mass market hit.

Android: today's Netscape

Apple's iPhone so devastated the existing players in the smartphone market that the only technology anyone else could use ended up being Google's poorly managed, technically inferior Android experiment, which was run like an arrogant pirate startup so assured of its victory that it laughed off its most serious competitor as a befuddled relic stuck in an anachronistic Walled Garden.

Android became the Netscape of the 2010 decade. Back in 1996, Netscape had similarly expected to destroy Microsoft's ubiquitous Windows platform by simply showing up and offering an "open" alternative, with only a weak idea about how it would fund that initiative if it gave away its web browser.

Despite the fact that Microsoft had initially completely failed to recognize the rise of the web, once it identified the much smaller Netscape as a threat it decisively leveraged its size, power and position to obliterate its rival and turn the web into another feature of Windows via Internet Explorer— which was an acquisition of the sort that Arment imagined today's Apple will be unable to similarly master in the realm of AI.

Targeting the profit center

Microsoft erased Netscape's power by effectively targeting its profit center: sales of web servers. Microsoft's own "good enough" IIS web server was bundled for free with Windows, sort of like how Apple bundled its own Maps and Spotlight search in iOS, erasing Google's ability to get paid for supplying search results. Apple has far more power to leverage its platform of a billion active devices to cut the advertising pipe supplying Google's revenues than Google or other AI vendors have in trying to get users to leave iOS

And really, if you want to talk about potential for disruption, Apple has far more power to leverage its platform of a billion active devices to cut the advertising pipe supplying Google's revenues than Google or other AI vendors have in trying to get users to leave iOS for a new platform with a verbal interface talking them through paid placement results.

Apple doesn't even have to do this on its own. European carriers are already looking at filtering out mobile ads on the network level in response to the massive data impact that surveillance-based advertising and user-tracking places on their networks.

Ten years of iOS

Fast forward to today— another five years later— and Apple's market cap is now about $540 billion (and that's over $200 billion less than its peak valuation reached last year, thanks to the current irrational stock panic cycle). The former RIM is now valued at less than $4 billion. Google's valuation is $503 billion (just $30 billion from its peak), and Microsoft is valued at $411 billion.

Those are all market caps, which reflect the mindset of investors and short term traders. Looking at revenues and profit, Apple brought in $227.5 billion over the last four quarters, and earned over $50 billion. Despite having a valuation near Apple's (and having briefly passed it on two occasions over the past quarter), Google only brought in $78 billion, and earned just $17 billion over the same period, close to 1/3 of Apple's actual profitability and revenues.

Microsoft earned just over $10 billion on sales of almost $87 billion. That's a fifth of Apple's profits, despite carrying a valuation three-fourths of Apple's. Also, Microsoft has slightly more employees than Apple's 110,000, while Google has roughly 55 percent as many.

Overall, that tells us that Apple has maintained a decade of solid growth while maintaining a rapidly expanding platform of mobile devices. No other vendor of smartphones or tablets or more conventional PCs has performed anything like Apple has over the past decade.

Google's incompetent handling of Android

While Android enthusiasts like to talk about Google maintaining some important share (or even market dominance!) of smartphones with Android, the reality is that Google has failed to benefit very much from the trend toward mobile devices over the past decade, both as an advertiser and most certainly as an aspiring hardware maker— a role it has performed so poorly at that it has all but abandoned its hardware hopes.

For Google to really transform the demand for smartphones, it needs to have some real power in the industry. But what it has done is actually fail repeatedly to deliver its ideas, first with Nexus, then using Motorola, then Android Silver and most recently Android One. Google's software platform exerts very little of the power Microsoft Windows had over PCs.

Over the past year, Google failed to even roll out its latest Android Marshmallow software to even a tenth of its users. Offering an AI app isn't going to dramatically shift its licensees' hardware from low end "carrier friendly, good enough" devices into profitable hardware on the level of iPhone.

Facebook and Amazon's epic failures in smartphones

Facebook and Amazon, two other AI espousing companies, feature stratospheric valuations and very little real profitability, but more importantly have dramatically failed to sell hardware or influence the smartphone market as intended. Facebook Phone and Facebook Home for Android were spectacular failures, and Amazon's own flopped effort to launch Fire Phone was just as poorly executed.

Even if Facebook, Amazon, Google or another competitor were able to launch a new product that did manage to begin changing the smartphone market and seriously threatening Apple's iPhone business, Apple would have years and scores of billions of dollars to leverage against them.

Did anyone notice what just occured in the "smartwatch" business? Apple showed up two years late and obliterated Android Wear and Samsung Tizen with its own much more expensive Apple Watch, paired with fashion styling that nobody in the commodity hardware business even thought about.

The future of computers

A decade ago, Apple was increasingly seen as "the iPod maker," to the point where Apple itself ditched "Computer" from its corporate name in 2007 when it introduced iPhone. Since the rise of iPhones, Apple has increasingly taken on the identity of the iPhone maker, and indeed iPhones now account for the majority of Apple's sales.

A key aspect of the iPhone's success is that Apple built it on top of its existing computing platform. Prior to iOS, Apple's product mix included ARM-based iPods and Airport Base Stations that were essentially standalone embedded computers with a singular purpose, but iPhone was a general purpose computing platform. So was iPad.

Today, Apple is a much larger computer maker than it was ten years ago, when it was still known as Apple Computer. Instead of making around 6 million Macs and an array of simpler, peripherals (including iPod), Apple now sells about 20 million Macs, 50 million iPads and around 250 million iPhones per year, along with about 12-15 million first-year sales of Apple Watch. Those ~340 million devices are all computers based on a similar core operating system.

Who will muscle into Apple's computing empire? Microsoft has proven that it can barely sustain its partners' Windows ecosystem, and its own Surface sales are hovering around 5 million annually, after three years of trying.

Google and its Android partners have done little but copy Apple's product for sale to a lower end demographic. However, that demographic is feeding iOS because an increasing number of Android users have been migrating to iPhones.

The consumption of computers is not going to end. It may shift, as it clearly has from desktop Windows PCs to handheld mobile computers (where Android plays the broad funnel feeding Apple's premium, profitable iPhone sales) and tablets (where Apple not only leads volume sales, but also makes virtually all the available profits).

It may also change slightly in character, as it has from PCs and tablets what IDC like to call "Detachables," a "new" category that Apple has already dominated with iPad Pro sales within its first three months— in competition against Microsoft's third year of Surface.

The computing market may also expand, as it has with wearables, which Apple also dominated with Apple Watch, already an even larger market than IDC's hybrid tablet-laptops.

And now that Apple has a variant of iOS working on both on a wearable device and in a home-oriented box with Apple TV, it has the potential to identify new kinds of small, dedicated computer devices that would benefit from the app platform and development tools its owns, and the Continuity features it has already used to stitch together Macs, iPods, iPhones and Apple Watch into a connected mesh.

Radically shifting Apple's customer base to a rival platform is going to be vastly more difficult than converting basic smartphone buyers to iPhone was for Apple in the last decade, or shifting conventional PC demand to a simpler, easier to manage iPad. Nobody assumed either of those migrations were even possible, let alone could be done so decisively within just a few years.

When a competitor introduces a new product that causes Apple's revenues to collapse by 75 percent (the way iPhone 6 gutted Samsung's entire mobile unit), we can start talking about the potential for Apple to retaliate with its massive cash hoard. Until then, the idea that the world will simply stop buying computers— because that's the only way Apple could fail— is hard to take seriously.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

-m.jpg)

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

Andrew O'Hara

Andrew O'Hara

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

-m.jpg)

78 Comments

Apple is clearly too big to fail. Cook will assign various tzars to control aspects of governing the corporation, which will ensure success in their relative fields. Once he cements support from Hillary and Vladamir, he will establish a trade agreement with both India and Iran that will push control of the mobile smart-device field well into the 2020's.

Wait... What am I saying?!?

Nothing worse than Business Insider. They are even worse than a British tabloid. (and that's really saying something)

BEFORE reading this long pro-Apple article, I visited the Arment article to remind myself of the information contained in it. At the time of my initial reading of the article, which was a week or two ago, I tweeted the article had a lot of ifs. I also tweeted would anyone dare to write an article about if Google is wrong. So far no blogger has taken up the dare. Instead of taking up the dare, a lot of bloggers ignored the ifs and just wrote about Apple missing out on the AI opportunity. They all forgot how they wrote about how bad the AI chat bots are as long as they could write about Apple not being in the game. Now, it is time to read this article.

Marco and his friends also stress that apple can no longer write software that they like using. They don't like photos, music, etc.

They are VERY down on apple

The Android vs iOS argument is very weak. I agree with the author that comparing profits is really all that matters in the long run. Also, the Android platform is really only good enough if you are not a serious app user. I use Android regularly as part of my job. Once you load apps up, the phone (even the newest flagships) crawl. Cache fills up, junk all over. It is a smart phone platform for people who only need to use the web, maps, and text. Android never matched Apple in the "app polish" category. If the game changes from apps (a big IF), then Apple may have a challenge. But for now, Android is architecturally an inferior OS.