A distributed denial of service (DDoS) attack that on Friday severely impacted internet access for many U.S. web denizens was found to be in part enabled by a botnet targeting unprotected "Internet of Things" devices. For Apple, the revelation vindicates a controversial walled garden approach to IoT borne out through the HomeKit protocol.

As detailed yesterday, unknown hackers set their sights on Dyn, an internet management company that provides DNS services to many major web entities.

A series of repeated attacks caused websites including The Verge, Imgur and Reddit, as well as services like HBO Now, and PayPal, to see slowdowns and extended downtimes. Follow-up waves played havoc with The New York Times, CNN, Netflix, Twitter and the PlayStation Network, among many others.

Though Dyn was initially unable to nail down a source, subsequent information published by security research firm Flashpoint revealed the targeted attacks involved a strain of the Mirai malware, reports Brian Krebs. Krebs has firsthand experience with Mirai, as the malware was deployed in a DDoS attack that brought down his website, KrebsOnSecurity, in September.

Mirai searches the web for IoT devices set up with default admin username and password combinations, Krebs says. Once discovered, the malware infiltrates and uses poorly protected hardware to facilitate a DDoS attack on an online entity, in this case Dyn.

Poor security practices are nothing new. Uninitiated or lazy end users have for decades left factory default settings untouched on routers, networked printers and other potential intrusion vectors. But this is different.

DVRs and IP cameras like those made by Chinese company XiongMai Technologies contain a grievous security vulnerability and are in large part responsible for hosting the botnet.

According to Krebs, DVRs and IP cameras made by Chinese company XiongMai Technologies, as well as other connected gadgets currently flooding the market, contain a grievous security vulnerability and are in large part responsible for hosting the botnet. As he explains, a portion of these devices can be reached via Telnet and SSH even after a user changes the default username and password.

"The issue with these particular devices is that a user cannot feasibly change this password," said Zach Wikholm, research developer at Flashpoint. "The password is hardcoded into the firmware, and the tools necessary to disable it are not present. Even worse, the web interface is not aware that these credentials even exist."

To prevent another Mirai attack, or a similar assault harnessing IoT hardware, offending devices might require a recall, Krebs says. Short of a that, unplugging an affected product is an effective stopgap.

By contrast, Apple's HomeKit features built-in end-to-end encryption, protected wireless chip standards, remote access obfuscation and other security measures designed to thwart hacks. Needless to say, it would be relatively difficult to turn a HomeKit MFi device into a DDoS zombie.

Announced in 2014 alongside iOS 8, HomeKit debuted as a secure framework onto which manufacturers of smart home products can lattice accessory communications. Specifically, the system uses iOS and iCloud infrastructure to securely synchronize data between host devices and accessories.

Apple details HomeKit protections in a security document posted to its website (PDF link), noting the system's reliance on public-private key pairs.

First, key pairs are generated on an iOS device and assigned to each HomeKit user. The unique HomeKit identity is stored in Keychain and synchronized to other devices via iCloud Keychain. Compatible accessories generate their own key pair for communicating with linked iOS devices. Importantly, accessories will generate new key pairs when restored to factory settings.

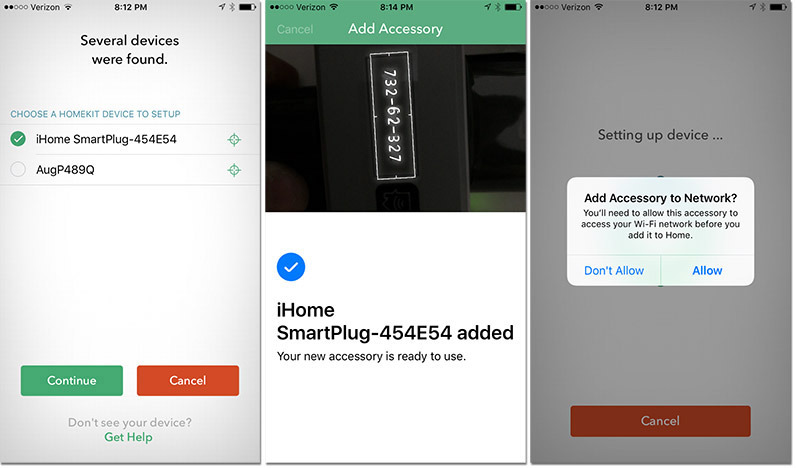

Apple uses the Secure Remote Password (3,072-bit) protocol to establish a connection between an iOS device and a HomeKit accessory via Wi-Fi or Bluetooth. Upon first use, keys are exchanged through a procedure that involves entering an 8-digit code provided by the manufacturer into a host iPhone or iPad. Finally, exchanged data is encrypted while the system verifies the accessory's MFi certification.

When an iPhone communicates with a HomeKit accessory, the two devices authenticate each other using the exchanged keys, Station-to-Station protocol and per-session encryption. Further, Apple painstakingly designed a remote control feature called iCloud Remote that allows users to access their accessories when not at home.

Accessories that support iCloud remote access are provisioned during the accessory's setup process. The provisioning process begins with the user signing in to iCloud. Next, the iOS device asks the accessory to sign a challenge using the Apple Authentication Coprocessor that is built into all Built for HomeKit accessories. The accessory also generates prime256v1 elliptic curve keys, and the public key is sent to the iOS device along with the signed challenge and the X.509 certificate of the authentication coprocessor.

Apple's coprocessor is key to HomeKit's high level of security, though the implementation is thought to have delayed the launch of third-party products by months. The security benefits were arguably worth the wait.

In addition to the above, Apple also integrates privacy safeguards that ensure only verified users have access to accessory settings, as well as privacy measures that protect against transmission of user-identifying or home-identifying data.

At its core, HomeKit is a well-planned and well-executed IoT communications backbone. The accessories only work with properly provisioned devices, are difficult to infiltrate, seamlessly integrate with iPhone and, with iOS 10 and the fourth-generation Apple TV (which acts as a hub), feature rich notifications and controls accessible via Apple's dedicated Home app. And they can't indiscriminately broadcast junk data to the web.

The benefits of HomeKit come at cost to manufacturers, mainly in incorporating Apple's coprocessor, but the price is undoubtedly less dear than recalling an unfixable finished product.

Mikey Campbell

Mikey Campbell

-xl-m.jpg)

-m.jpg)

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Chip Loder

Chip Loder

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

-m.jpg)

29 Comments

Happy to read this. The high price one pays for Apple products, and apparently its inbuilt security, not only protects the owner but others as well.

Sounds like these vulnerable devices are the Takata airbags of the IoT world.

The biggest complaint I've seen about companies wanting to use HomeKit is Apples requirement for encryption and using a specific processor for this. I bet those companies will not feel the same now.

I could see Apple working this into their keynote on Oct 27th and talking up theirs security/privacy. I could also see companies selling HomeKit compatible devices using this in their advertising. This was a real and significant problem that affected a lot of people, and was traced to a very specific cause (cheap home devices with little to no security).

This can only be good for Apple, but they need to promote it better.

I have ordered upgraded wifi hardware for my heating system to make it compatible with HomeKit. The manufacturer has recently informed me there will be a delay with supply as it is taking longer than expected to get the hardware appooved. I guess this means Apple are not approving quickly. If Apple are serious about HomeKit then they need to put more resources into supporting hardware manufacturers. A similar view has been expressed about ApplePay in that Apple should be doing more to get the retailers on board.

Apple should lead the band wagon to get these devices recalled and ban similar devices.