Apple's new MacBook and MacBook Pro models contain more innovation than just their case design, graphics, and the improved accessibility of their internals. Here's a look at other details related to FireWire, USB, and the new NVIDIA-based controller that replaces Intel's chipset.

Only the MacBook Pro supports FireWire; it supplies the faster FW800 (800Mbps) standard, which is backwardly compatible with the original FW400 (400Mbps). A FW800 port can handle a chain of devices running at either 400 or 800Mbps, and manages data transfers over the bus at the top speed of the device. FireWire does not slow the entire bus down to the speed of the slowest device attached.

The complete lack of FireWire on the standard 13" MacBook means it can't be used in Target Disk Mode, as USB lacks the bus intelligence to support such a system. This also means that MacBook users will need to use the Ethernet-based Migration Assistant developed for the MacBook Air to import files and settings from their previous system, although in the case of the MacBook, this will be considerably faster due to its support for Gigabit Ethernet; the MacBook Air is limited to 10/100 Fast Ethernet, and that is only available when using the optional Ethernet dongle. Out of the box, the Air only supports importing files from an older Mac using Migration Assistant over wireless networking, which many reviewers reported to be very slow and problematic.

Gigabit Ethernet (1000Mbps) is nominally faster than FireWire 400, although it also incurs more overhead related to Ethernet networking than FireWire does. It is far faster than wireless 802.11n, which has a comparable throughput throughput maximum of 300Mbps, a feat that can only be approached in ideal wireless signal conditions.

Another alternative to FireWire Target Disk Mode is the use of Migration Assistant with a USB-connected Time Machine backup, or a direct import from a USB volume containing the previous system's files. This may require removing the hard drive from the old system and installing it into a USB hard drive enclosure. Of course, that's far less convenient than booting it up into FireWire Target Disk Mode.

To perform the reverse (exposing the data from the new MacBook's internal drive as if it were in Target Disk Mode), users will have to remove the MacBook's hard drive and insert it into a USB hard drive enclosure that supports a mini-SATA drive connection. Note that many cheap USB disk enclosures only support notebook drives with mini-ATA connectors, or full size PATA or SATA connectors.

While there are some workarounds to the MacBook's lack of FireWire Target Disk Mode, the missing port is also a problem for users with FireWire peripherals. FireWire is used by musicians to patch together audio equipment and by video filmmakers to connect to FireWire camcorders for video import. Apple's push for FireWire adoption was successfully thwarted by Intel's USB 2.0, leading to a market reality where high volume PC manufacturers overwhelmingly aligned behind the simpler, cheaper USB in favor of adopting the more functional, intelligent, and faster, but subsequently more expensive, FireWire standard.

Apple was forced to respond by first adding USB support to the iPod, and has since removed FireWire support entirely on the iPod and iPhone to cut costs and complexity. Its removal from the MacBook will force users who need FireWire to consider the old white MacBook on the low end, or the full size MacBook Pro on the high end. The MacBook also lacks an ExpressCard expansion slot to add FireWire features as an aftermarket option. Likewise, the MacBook Air lacks FireWire as well and any way to add support for it. The promise of FireWire was not only derailed by USB 2.0 on the low end on most peripherals, but has also been supplanted by SATA and eSATA on the higher end in hard drive applications, leaving FireWire with an increasingly small niche.

USB

Both the MacBook and MacBook Pro supply two USB 2.0 ports, of which Apple's documentation says that only one of which is "high powered." In the USB 2.0 specification, high-powered means suitable for powering certain peripherals that require more than 100mA. Any device that draws significant power or charges itself over USB, such as an iPod, a USB hard drive, or a USB scanner lacking a power source, needs to be plugged into a high-powered USB port.

A low powered port is fine for keyboards, mice, or other passive devices, as well as any devices that supply their own power, such as a printer or full sized USB hard drive that has its own power adapter. An external, powered USB hub will supply the necessary power when using either USB port. However, both USB ports actually supply at least 500mA, enough to each power and charge an iPhone or similar product at the same time.

The two ports are two separate, 480Mbps high speed USB 2.0 busses. The front port is shared internally with the built-in iSight camera. Apple's documentation says the first USB device to be plugged in that demands more than 500mA will get 1000mA, and other devices will all be limited to 500mA or less. This indicates that users will have nothing new to worry about; anyone using higher-powered devices may need to use a powered USB hub, but this does not represent a change for MacBook Pro users.

Internal Busses

As with earlier MacBooks, the slower 12Mbps USB 1.0 is used internally to drive the keyboard, trackpad, Bluetooth, and IR remote sensor, none of which have any need for a faster USB 2.0 connection. As noted above, the internal iSight camera connects internally to one of the faster USB 2.0 busses.

AirPort wireless networking is interfaced with the NVIDIA 'chipset on a chip' via PCIe, and all other peripherals, drives, audio, video, and RAM are similarly managed by the same chip. While most Intel-based PCs use two primary support chips to interface the various components, the new MacBooks use one. The MacBook Pro uses the same architecture while also supplying an additional, dedicated NVIDIA GPU.

Conventional Intel PCs traditionally split controller chipset functions into two components, a "northbridge" that interfaces with the CPU and manages the high performance system RAM and the fast PCIe bus that typically drives dedicated video and expansion slots, and the southbridge chip, which handles the less demanding general I/O functions, including audio, Ethernet, USB, system clock, power management, and other functions that don't demand the fastest possible bus. This split helps keep the northbridge as fast as possible while allowing the southbridge to run slower, and therefore handle cheaper components.

The definition of northbridge and southbridge have shifted slightly with new technologies and between manufacturers; Intel now refers to the northbridge as the Memory Controller Hub or MCH, and the southbridge as the I/O Controller Hub or ICH.

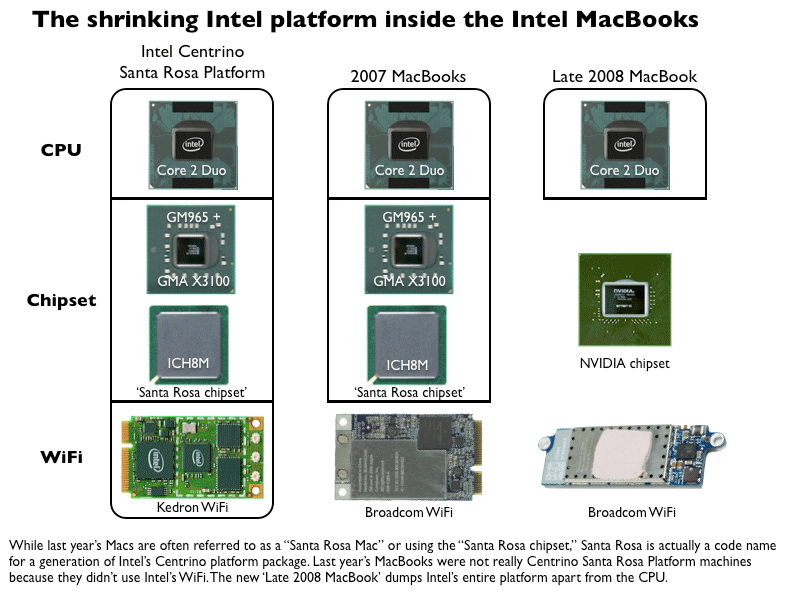

Chipsets and Platforms

When Intel talks about its "platforms," such as the Centrino Santa Rosa, it's branding a CPU, a chipset, and wireless controller under an umbrella brand. Last year's MacBooks used the "Santa Rosa" combination of Intel's Core 2 Duo Merom CPU, paired with the Intel Mobile 965 Express series chipset. That chipset included the GM965 Crestline MCH northbridge using Intel's GMA X3100 graphics technology and ICH8M southbridge.

However, the definition of Intel's Centrino-branded Santa Rosa platform also includes the Intel WiFi Link 4965AGN Kedron wireless chip. Apple didn't use Intel's part for WiFi on the 2007 MacBooks; it used the Broadcom BCM4328. The "Santa Rosa MacBook" was therefore not really Santa Rosa nor a Centrino notebook. That's why Apple never refers to it as a Santa Rosa or Centrino Mac.

Many PC makers are content to source all their components from one vendor, and Intel is obviously happy to bundle all of its components together under a brand name that suggests to consumers that "Centrino" is a feature they need. However, Apple has historically always selected the best parts available for its desired design goals. Last year, that meant skipping Intel's WiFi chip. In the year since, Apple has been plagued with reports of problems related to MacBook graphics, forcing the company to rethink its use of Intel's relatively uninspiring integrated graphics options.

Add in the fact that NVIDIA could offer a replacement northbridge/southbridge controller in one chip combined with far better integrated graphics performance, and it's no wonder why Apple dropped Intel's 2008 Montevina Centrino platform entirely for its new generation of MacBooks. The new MacBook, MacBook Air, and MacBook Pro all use continue to use Intel's Core 2 Duo Penryn CPUs, but pair NVIDIA's GeForce 9400M G chipset and integrated graphics along with AirPort WiFi supplied by a Broadcom BCM94322USA. Apple is expected to continue its expansion of using competitive components, and possibly even custom parts of its own design, rather than simply branding Intel "platforms" as Macs. This will also make it harder for observers to guess what features Apple's next Macs will have, although that's obviously not Apple's primary motivation.

Other Segments from our Inside the new MacBooks series

Apple details new MacBook manufacturing process

A closer look at Apple's move to NVIDIA chipsets, DisplayPort

Prince McLean

Prince McLean

-m.jpg)

Brian Patterson

Brian Patterson

Charles Martin

Charles Martin

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

58 Comments

Just a correction...

In your first diagram it states that the late 2008 MacBooks use DDR2 1067 RAM when in fact they use DDR3 1067

Interesting, didn't know the new MBP USB, 1 is high powered and the other is not. I wonder how is the previous MBP USB?

I think this was a very smart move. Reducing the number of chips on the logic board while increasing performance. Brilliant.

I think this was a very smart move. Reducing the number of chips on the logic board while increasing performance. Brilliant.

Get back in your cube before Steve walks by.

Just a correction...

In your first diagram it states that the late 2008 MacBooks use DDR2 1067 RAM when in fact they use DDR3 1067

Yep! Thanks a bunch. Should be corrected now.

K