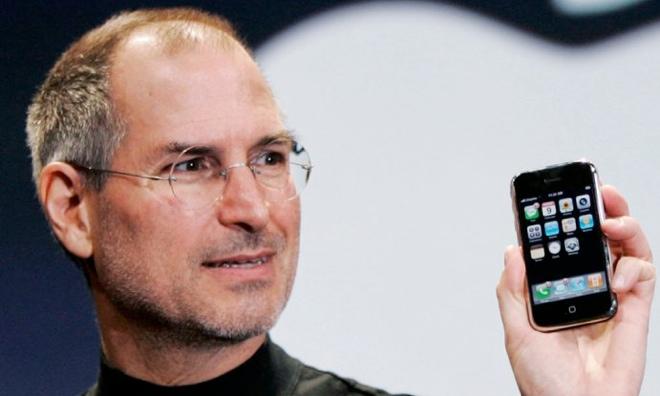

While Steve Jobs was on stage unveiling the first iPhone for the world, the engineers behind the device were in the audience halfway drunk, says a new report that takes a look behind-the-scenes of the development of the most popular smartphone in the world.

The engineers and managers were downing Scotch in the fifth row of the Moscone Center as Apple's co-founder demonstrated an aspect of the iPhone. According to a new write-up in The New York Times Magazine, they were all quite nervous that the still-incomplete iPhone prototype would fail to perform some task during the demonstration, and whoever had been responsible for that feature prior to the demo would later have to suffer the wrath of Jobs.

The Times' look back at the development of the iPhone reveals a process filled with setbacks, glitches, and obstacles. Andy Grignon, a senior radio engineer at Apple, contributes a first-hand perspective on the process, one filled with stress and high stakes.

“At first it was just really cool to be at rehearsals at all — kind of like a cred badge,†Grignon said of the rehearsals that preceded the actual iPhone unveiling. “But it quickly got really uncomfortable. Very rarely did I see him become completely unglued — it happened, but mostly he just looked at you and very directly said in a very loud and stern voice, ‘You are [expletive] up my company,’ or, ‘If we fail, it will be because of you.’ He was just very intense. And you would always feel an inch tall.â€

Before those rehearsals, Apple was on lockdown. Apple is well known for its culture of secrecy, and the development of the iPhone was no different. Engineers were asked to sign non-disclosure agreements before they could even be told what they were working on, and then they were asked to sign documents reaffirming the previous agreements. "Rockstar" employees began disappearing from their departments, only to be seen later entering rooms with badge scanners and multiple other levels of security. The secrecy was aimed at preventing any leaks of what employees would soon find out was a "moon shot" of sorts for the then-iPod maker.

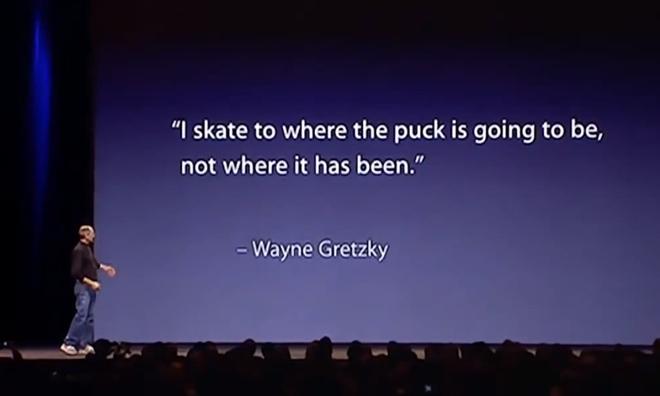

"It had been drilled into everyone’s head that this was the next big thing to come out of Apple," Grignon said, as the iPhone was essentially the only big, new product Apple had been working on at the time. “It was Apple TV or the iPhone... And if he had gone to Macworld with just Apple TV†— a new product that connected iTunes to a television set — “the world would have said, ‘What the heck was that?’ â€

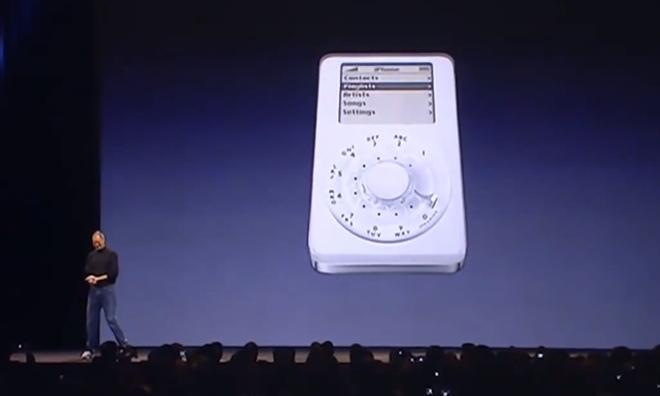

The iPhone project — which would eventually cost $150 million to create, by some estimates — produced a number of prototypes. Among them was a device that looked like a joke slide Jobs showed before introducing the real iPhone: an iPod with a rotary dial in place of the click wheel. That design was rejected, as it "was not cool" in the way Apple wanted its products to be.

The team behind the iPhone's development came to realize that their earlier idea that building the device would be like building a small Mac was quite off the mark. Issues arose with battery life, the multitouch interface, and even build materials. Jobs and Apple design guru Jony Ive initially designed an iPhone made entirely from brushed aluminum; they had to be gently let down by Apple's antenna experts that such a design would block radio waves, rendering the device "a beautiful brick."

“And it was not an easy explanation," said Phil Kearney, a former Apple engineer. "Most of the designers are artists. The last science class they took was in eighth grade. But they have a lot of power at Apple. So they ask, ‘Why can’t we just make a little seam for the radio waves to escape through?’ And you have to explain to them why you just can’t.â€

By the time the actual device was unveiled in San Francisco, nerves were frayed throughout the development team. The process was fraught with slammed doors, shouting matches, and exhausted engineers quitting in a huff, only to return once they had gotten a few nights' sleep. When the finale came — and it worked along with everything before it, we all just drained the flask.

The device that Jobs actually took onto the stage with him was actually an incomplete prototype. It would play a section of a song or video, but would crash if a user tried to play the full clip. The apps that were demonstrated were incomplete, with no guarantee that they would not crash mid-demonstration. The team eventually decided on a "golden path" of specific tasks that Jobs could perform with little chance that the device would crash in the actual keynote.

Jobs took the stage on January 9, 2007 in his trademark black turtleneck and jeans, saying "This is a day I have been looking forward to for two and a half years," before showing off Apple's revolutionary take on the phone. Grignon, by that time, was drunk, having brought a flask in order to calm his nerves. As Jobs swiped and pinched, some of his staff swigged and sighed in relief, each one taking a shot as the feature they were responsible for performed without a hitch.

"When the finale came," Grignon said, "and it worked along with everything before it, we all just drained the flask. It was the best demo any of us had ever seen. And the rest of the day turned out to be just a [expletive] for the entire iPhone team. We just spent the entire rest of the day drinking in the city. It was just a mess, but it was great.â€

Kevin Bostic

Kevin Bostic

-m.jpg)

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

Andrew O'Hara

Andrew O'Hara

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Mike Wuerthele

Mike Wuerthele

Bon Adamson

Bon Adamson

-m.jpg)

47 Comments

I guess SJ just didn't want to wait for 3 years to tell the world about iPhone then.

From the bio, hope this is not plagiarism: [quote]Three Revolutionary Products in One An iPod That Makes Calls By 2005 iPod sales were skyrocketing. An astonishing twenty million were sold that year, quadruple the number of the year before. The product was becoming more important to the company’s bottom line, accounting for 45% of the revenue that year, and it was also burnishing the hipness of the company’s image in a way that drove sales of Macs. That is why Jobs was worried. “He was always obsessing about what could mess us up,” board member Art Levinson recalled. The conclusion he had come to: “The device that can eat our lunch is the cell phone.” As he explained to the board, the digital camera market was being decimated now that phones were equipped with cameras. The same could happen to the iPod, if phone manufacturers started to build music players into them. “Everyone carries a phone, so that could render the iPod unnecessary.” His first strategy was to do something that he had admitted in front of Bill Gates was not in his DNA: to partner with another company. He began talking to Ed Zander, the new CEO of Motorola, about making a companion to Motorola’s popular RAZR, which was a cell phone and digital camera, that would have an iPod built in. Thus was born the ROKR. It ended up having neither the enticing minimalism of an iPod nor the convenient slimness of a RAZR. Ugly, difficult to load, and with an arbitrary hundred-song limit, it had all the hallmarks of a product that had been negotiated by a committee, which was counter to the way Jobs liked to work. Instead of hardware, software, and content all being controlled by one company, they were cobbled together by Motorola, Apple, and the wireless carrier Cingular. “You call this the phone of the future?” Wired scoffed on its November 2005 cover. Jobs was furious. “I’m sick of dealing with these stupid companies like Motorola,” he told Tony Fadell and others at one of the iPod product review meetings. “Let’s do it ourselves.” He had noticed something odd about the cell phones on the market: They all stank, just like portable music players used to. “We would sit around talking about how much we hated our phones,” he recalled. “They were way too complicated. They had features nobody could figure out, including the address book. It was just Byzantine.” George Riley, an outside lawyer for Apple, remembers sitting at meetings to go over legal issues, and Jobs would get bored, grab Riley’s mobile phone, and start pointing out all the ways it was “brain-dead.” So Jobs and his team became excited about the prospect of building a phone that they would want to use. “That’s the best motivator of all,” Jobs later said. Another motivator was the potential market. More than 825 million mobile phones were sold in 2005, to everyone from grammar schoolers to grandmothers. Since most were junky, there was room for a premium and hip product, just as there had been in the portable music-player market. At first he gave the project to the Apple group that was making the AirPort wireless base station, on the theory that it was a wireless product. But he soon realized that it was basically a consumer device, like the iPod, so he reassigned it to Fadell and his teammates. Their initial approach was to modify the iPod. They tried to use the trackwheel as a way for a user to scroll through phone options and, without a keyboard, try to enter numbers. It was not a natural fit. “We were having a lot of problems using the wheel, especially in getting it to dial phone numbers,” Fadell recalled. “It was cumbersome.” It was fine for scrolling through an address book, but horrible at inputting anything. The team kept trying to convince themselves that users would mainly be calling people who were already in their address book, but they knew that it wouldn’t really work. At that time there was a second project under way at Apple: a secret effort to build a tablet computer. In 2005 these narratives intersected, and the ideas for the tablet flowed into the planning for the phone. In other words, the idea for the iPad actually came before, and helped to shape, the birth of the iPhone. Multi-touch One of the engineers developing a tablet PC at Microsoft was married to a friend of Laurene and Steve Jobs, and for his fiftieth birthday he wanted to have a dinner party that included them along with Bill and Melinda Gates. Jobs went, a bit reluctantly. “Steve was actually quite friendly to me at the dinner,” Gates recalled, but he “wasn’t particularly friendly” to the birthday guy. Gates was annoyed that the guy kept revealing information about the tablet PC he had developed for Microsoft. “He’s our employee and he’s revealing our intellectual property,” Gates recounted. Jobs was also annoyed, and it had just the consequence that Gates feared. As Jobs recalled: This guy badgered me about how Microsoft was going to completely change the world with this tablet PC software and eliminate all notebook computers, and Apple ought to license his Microsoft software. But he was doing the device all wrong. It had a stylus. As soon as you have a stylus, you’re dead. This dinner was like the tenth time he talked to me about it, and I was so sick of it that I came home and said, “**** this, let’s show him what a tablet can really be.” Jobs went into the office the next day, gathered his team, and said, “I want to make a tablet, and it can’t have a keyboard or a stylus.” Users would be able to type by touching the screen with their fingers. That meant the screen needed to have a feature that became known as multi-touch, the ability to process multiple inputs at the same time. “So could you guys come up with a multi-touch, touch-sensitive display for me?” he asked. It took them about six months, but they came up with a crude but workable prototype. Jony Ive had a different memory of how multi-touch was developed. He said his design team had already been working on a multi-touch input that was developed for the trackpads of Apple’s MacBook Pro, and they were experimenting with ways to transfer that capability to a computer screen. They used a projector to show on a wall what it would look like. “This is going to change everything,” Ive told his team. But he was careful not to show it to Jobs right away, especially since his people were working on it in their spare time and he didn’t want to quash their enthusiasm. “Because Steve is so quick to give an opinion, I don’t show him stuff in front of other people,” Ive recalled. “He might say, ‘This is shit,’ and snuff the idea. I feel that ideas are very fragile, so you have to be tender when they are in development. I realized that if he pissed on this, it would be so sad, because I knew it was so important.” Ive set up the demonstration in his conference room and showed it to Jobs privately, knowing that he was less likely to make a snap judgment if there was no audience. Fortunately he loved it. “This is the future,” he exulted. It was in fact such a good idea that Jobs realized that it could solve the problem they were having creating an interface for the proposed cell phone. That project was far more important, so he put the tablet development on hold while the multi-touch interface was adopted for a phone-size screen. “If it worked on a phone,” he recalled, “I knew we could go back and use it on a tablet.” Jobs called Fadell, Rubinstein, and Schiller to a secret meeting in the design studio conference room, where Ive gave a demonstration of multi-touch. “Wow!” said Fadell. Everyone liked it, but they were not sure that they would be able to make it work on a mobile phone. They decided to proceed on two paths: P1 was the code name for the phone being developed using an iPod trackwheel, and P2 was the new alternative using a multi-touch screen. A small company in Delaware called FingerWorks was already making a line of multi-touch trackpads. Founded by two academics at the University of Delaware, John Elias and Wayne Westerman, FingerWorks had developed some tablets with multi-touch sensing capabilities and taken out patents on ways to translate various finger gestures, such as pinches and swipes, into useful functions. In early 2005 Apple quietly acquired the company, all of its patents, and the services of its two founders. FingerWorks quit selling its products to others, and it began filing its new patents in Apple’s name. After six months of work on the trackwheel P1 and the multi-touch P2 phone options, Jobs called his inner circle into his conference room to make a decision. Fadell had been trying hard to develop the trackwheel model, but he admitted they had not cracked the problem of figuring out a simple way to dial calls. The multi-touch approach was riskier, because they were unsure whether they could execute the engineering, but it was also more exciting and promising. “We all know this is the one we want to do,” said Jobs, pointing to the touchscreen. “So let’s make it work.” It was what he liked to call a bet-the-company moment, high risk and high reward if it succeeded. A couple of members of the team argued for having a keyboard as well, given the popularity of the BlackBerry, but Jobs vetoed the idea. A physical keyboard would take away space from the screen, and it would not be as flexible and adaptable as a touchscreen keyboard. “A hardware keyboard seems like an easy solution, but it’s constraining,” he said. “Think of all the innovations we’d be able to adapt if we did the keyboard onscreen with software. Let’s bet on it, and then we’ll find a way to make it work.” The result was a device that displays a numerical pad when you want to dial a phone number, a typewriter keyboard when you want to write, and whatever buttons you might need for each particular activity. And then they all disappear when you’re watching a video. By having software replace hardware, the interface became fluid and flexible. Jobs spent part of every day for six months helping to refine the display. “It was the most complex fun I’ve ever had,” he recalled. “It was like being the one evolving the variations on ‘Sgt. Pepper.’” A lot of features that seem simple now were the result of creative brainstorms. For example, the team worried about how to prevent the device from playing music or making a call accidentally when it was jangling in your pocket. Jobs was congenitally averse to having on-off switches, which he deemed “inelegant.” The solution was “Swipe to Open,” the simple and fun on-screen slider that activated the device when it had gone dormant. Another breakthrough was the sensor that figured out when you put the phone to your ear, so that your lobes didn’t accidentally activate some function. And of course the icons came in his favorite shape, the primitive he made Bill Atkinson design into the software of the first Macintosh: rounded rectangles. In session after session, with Jobs immersed in every detail, the team members figured out ways to simplify what other phones made complicated. They added a big bar to guide you in putting calls on hold or making conference calls, found easy ways to navigate through email, and created icons you could scroll through horizontally to get to different apps—all of which were easier because they could be used visually on the screen rather than by using a keyboard built into the hardware.[/quote]

[quote name="mubaili" url="/t/159938/behind-the-scenes-details-reveal-steve-jobs-first-iphone-announcement#post_2411536"]based the check from this site [URL=http://iphone-check.herokuapp.com/]http://iphone-check.herokuapp.com/[/URL], it only seems the 16G grey one is readily available, which is a good thing. It means people do want and are willing to pay at least $100 more for more capacity, which boost Apple's margin, cause a 16GB more storage cost way less than $100. Hooray!!! [/quote] It's $20 for the extra 16GB for Apple, $29 for the additional 48GB in the largest model. Maybe I should start that line with 'supposedly'

It's hard to believe where we've come in just six short years, thanks to Apple!

[quote name="PhilBoogie" url="/t/159938/behind-the-scenes-details-reveal-steve-jobs-first-iphone-announcement#post_2411538"][/quote] Leander Kahney had a bio of Jony Ive coming out in November. He says he got a number of current and former Apple employees to talk. It will be interesting to see how much of that book jives with Walter Isaacson's bio or other stories we've head over the years. I heard Kahney talk about his book on a podcast once and I got the impression that the way things have been recounted over the years weren't always accurate. At least according to the employees he interviewed.