The forensic tool known as 'GrayKey' has grave privacy and security implications, a report into the iPhone-unlocking tool suggests, as it has the potential of being misused by thieves and other criminals if the compact device is stolen from members of law enforcement.

The recently surfaced 'GrayKey' tool from startup Grayshift offers a way for government agencies and members of law enforcement to gain access to an iPhone without sending it off for analysis by security analysts. The tool is marketed as being able to extract the full filesystem from an iPhone, and is able to perform brute-force passcode attacks against the device in a short period of time.

An anonymous source of MalwareBytes Labs reveals it to be a small gray box, measuring four inches square by two inches deep, with two Lightning cables on the front of the device allowing two iPhones to be connected at the same time.

The iPhones can be disconnected from the unit after about two minutes, but after disconnection, software will continue running on the iPhones to crack the security, later showing the passcode and other details on the iPhone's screen. The source advised the time for this process can vary from two hours for shorter passcodes up to three days or longer for six-digit versions.

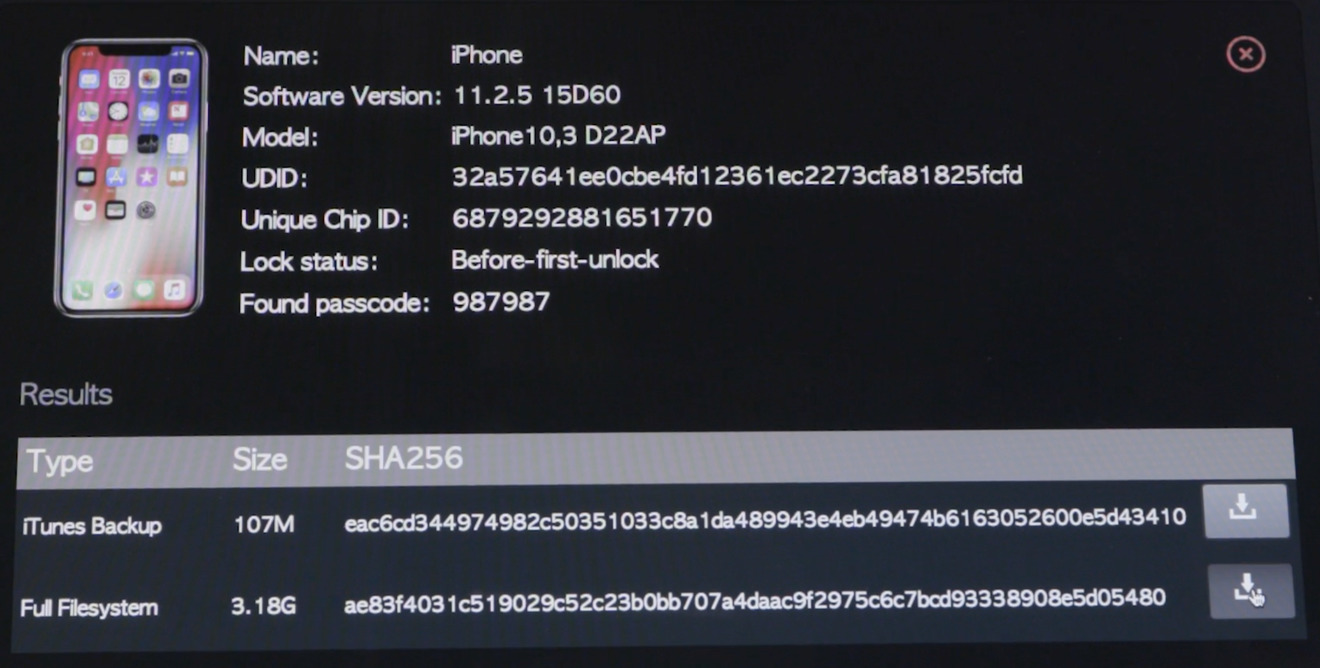

After unlocking, the iPhone can be connected back to the GrayKey device to download the full contents of the filesystem, which are accessible through a web-based interface on a connected computer. This includes the unencrypted contents of the iPhone's onboard keychain.

Screenshots supplied to the report reveal it will work with newer iPhones, including the iPhone X, and will work on iOS releases up to 11.2.4.

Two versions of the GrayKey are offered, starting from $15,000 for a model that is strictly geofenced and requiring Internet connectivity to function, as well as having a limit to the number of unlocks it can perform. The $30,000 version has no unlock limit and doesn't require an Internet connection to function, though it does use token-based two-factor authentication instead of geofencing for security, meaning it can be taken to different locations and used practically anywhere.

MalwareBytes notes that given the tendency for people to ignore security protocols for the sake of convenience, like putting a password on a sticky note attached to a monitor, there is a good chance the token used to secure the more expensive version will be kept relatively nearby the GrayKey itself.

This complacency could make the GrayKey and its token far easier to steal, and be used by criminals, the report hints, due to the small pocketable size and the ability to continue working offsite. The hardware could potentially fetch a high price on the black market, due to being able to unlock stolen iPhones for resale, and to access highly valuable personal data of their owners.

The report also posits the possibility that the GrayKey could be using some sort of jailbreak to gain access, questioning if it remains jailbroken if the iPhone is returned to the owner, further adding the possibility of remote access to it by others.

While suspects are the likely targets for the tool, the state of the iPhone after the process may also be an issue for witnesses providing their devices to law enforcement with their consent. If a passcode isn't given by the witness, the technician extracting the data may elect to use GrayKey instead, which could leave the iPhone in a vulnerable unlocked state when it is returned.

The security of the network-limited version is also unknown, with further questions asked about whether it can be remotely accessed, if the data can be intercepted in transit, and even if the phone data is stored securely once acquired.

As it is unclear if sales are just limited to law enforcement in the US or to other agencies in the rest of the world, the report raises the prospect of its misuse by "agents of an oppressive regime." It is also suggested the device could end up being reverse engineered, reproduced, and sold by an enterprising hacker at a cheaper price to any criminal who wants their own unit.

"The existence of the GrayKey isn't hugely surprising, nor is it a sign that the sky is falling," sums up the report. "However, it does mean that an iPhone's security cannot be ensured if it falls into a third party's hands."

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

-m.jpg)

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

Mike Wuerthele

Mike Wuerthele

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

Wesley Hilliard

Wesley Hilliard

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

17 Comments

This is bad, a lot of police enforcement is corrupt & linked to theives. There must be a shield for the good.

I want to know more about this. How does it deal with 10 failed attempts and erase? Do we have proof this works or is even a real thing?

I am confident that the bad guys have already gotten their hands on these. However I am even more confident that Apple has, or shortly will, get ahold of one and figure out a way to block it from working. EDIT: I just had a thought. What will happen is that these will fall into the hands of criminals. Within a couple of weeks cheap black market copies out of the far east will flood the market. The value will crash and the original developers will end up making little if anything off of their invention. I'll be back here LMAO

The good thing is it takes more than 3 days for a 6 digit number password. So using a longer password with numbers and text will massively increase the time and therefore making it worthless.