A lot has been made about Apple's possible shift to the A-series processor in the Mac starting in 2020 — but this isn't the first time that Apple has convinced a generation to change hardware architectures.

A pair of reports from Bloomberg's Mark Gurman in the last six months have discussed the possibility of at the very least a permeable membrane between iOS and macOS from the software side. On the outside, the latest reports suggest a shift to the ARM-based A-series processor in at least some Macs, starting in 2020.

While shouted from the highest mountain-tops by mainstream media and tech publications alike, these aren't earth-shattering revelations by any means. The writing on the wall portending a shift to Apple's A-series ARM-based processor has been there for at least three years.

This migration is being bandied about as something unparalleled, and that makes no sense. Apple has convinced its devout to shift to new hardware architectures in the Mac itself twice. But, it's actually hurdled the potential marketing nightmare of large shifts for users many times — and at least one AppleInsider staffer was there for all of them.

Apple II to Mac

Apple's first big product for consumers was the Apple II series. Without delving too deeply into the history of the foundational device, the line spanned six major releases with around six million made in total since the Apple II launch in 1977 and the final discontinuation in 1993.

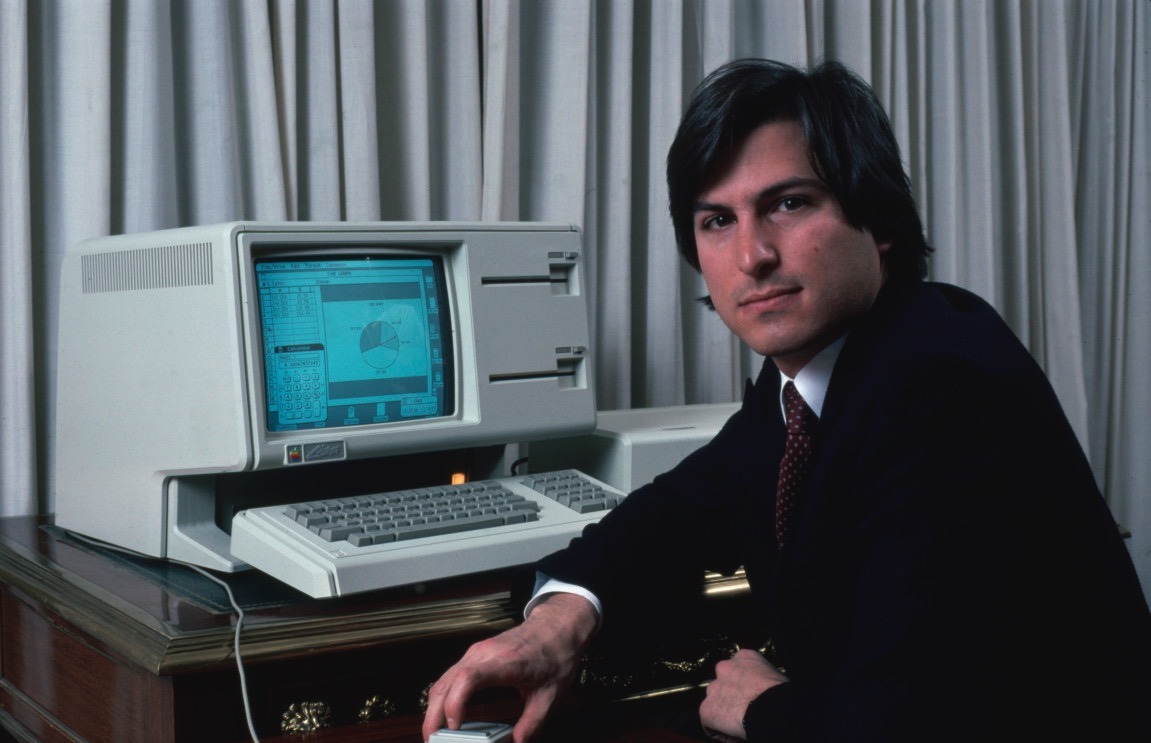

But, in 1983, Apple saw the future. It was the Lisa, and then the first Macintosh in 1984. The Mac and the Apple II series continued in parallel for a while, but by the late '80s, it was clear where Apple's focus was going.

In 1991, Apple released the Apple IIe card for the Macintosh LC series as a stop-gap measure to help school migrate. It was produced until mid-1995 after the Power Macintosh was released.

Apple didn't have to do much in the way of public relations damage control, given the relatively small computer user base at the time. It was mostly done by fiat — but the IIe card for the Macintosh LC was Apple's nod in the direction of necessary migration tools.

The Usenet, and dial-in bulletin boards of the day were relatively aflame with complaints about the shift, and Apple's abandonment of them. The "Apple II Forever" movement, originally started by Apple, picked up some steam, and a few die-hards are still fans of the hardware, and are updating at least the Apple IIgs operating system and ProDOS to this day.

68k to PPC

Mac users saw a lot of changes in just a decade, starting with the 68000-based Mac 128. The Mac II with color shipped in 1987 for about $5500 with a monitor, with the "wicked fast" IIfx shipping in 1990 for nearly $10,000 giving users 40Mhz of blistering speed in a 68030 processor. The Quadra line with the 68040 capped the line in 1991, and ended in a big shift.

Just a decade after the first true Macintosh, Apple announced the Power Macintosh 6100, 7100, and 8100 — and a new hardware architecture. The new machines launched with System 7.1.2 and emulated 68K processor code, and as a result were a fraction of the speed of the native speeds possible on the Quadras of the day.

As expected, this caused some AOL-communicated drama. The nascent internet helped with this transition, as it was getting easier to download patches for software.

Software distribution was handled both by the emulation of older hardware, plus a "Fat Binary" where 68K and PowerPC code existed in the same executable. This had an impact on storage measured in megabytes, and a pocket-industry popped up for apps that would strip the binary you didn't need out of the app.

The last operating system release for the 68K-series Macs was MacOS 8.1. Technically, the Classic environment in Mac OS X maintained support for 68K code, but other considerations with the system software and other hardware considerations like larger displays precluded early, old software from running properly.

OS 9 to OS X

Just a few years after the shift to Power PC, a lot of publicity swirled around Copland, which never saw the light of day, and Apple's acquisition of NeXT. Also at about this time, users were deriding the stability of OS 9, Steve Jobs came back and killed a large array of Apple products.

The first Mac OS X Developer's preview launched in May 1998. The evolution of the iMac continued with the iMac DV — which was really the first iMac suitable for Mac OS X.

A public beta of Mac OS X came along in September of 2000, with the first full release, codenamed Cheetah, in March of 2001. Mac OS X 10.1 Puma came along less than a year later.

Steve Jobs famously put OS 9 in a coffin in 2002. It wouldn't be completely put to pasture until Mac OS X 10.5 in June 2006. PowerPC hardware was finally left behind with the release Mac OS X 10.6 Snow Leopard in June of 2008, but the software soldiered on for a bit longer.

Apple made a big move in 2003, ensuring future transitions would be a bit easier. It essentially mandated Xcode as the one true developer's platform. Apple clearly had a plan, as it was later required to develop software for iOS — which was in the very, very early stages of conceptualization at that time.

PowerPC to Intel

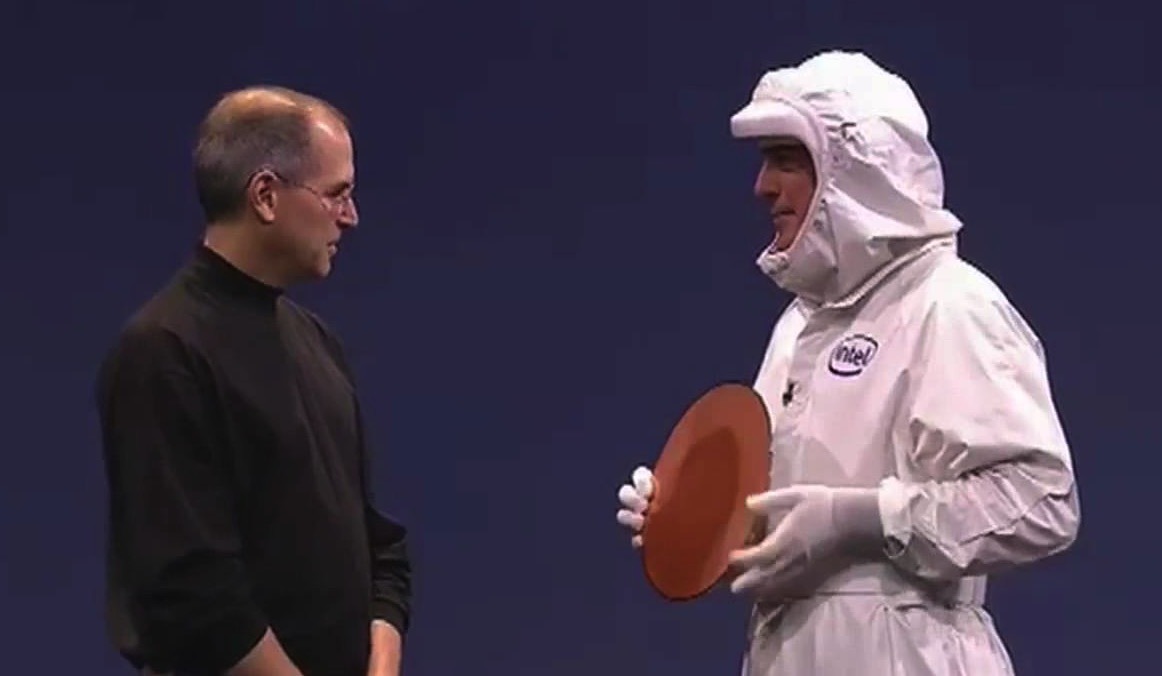

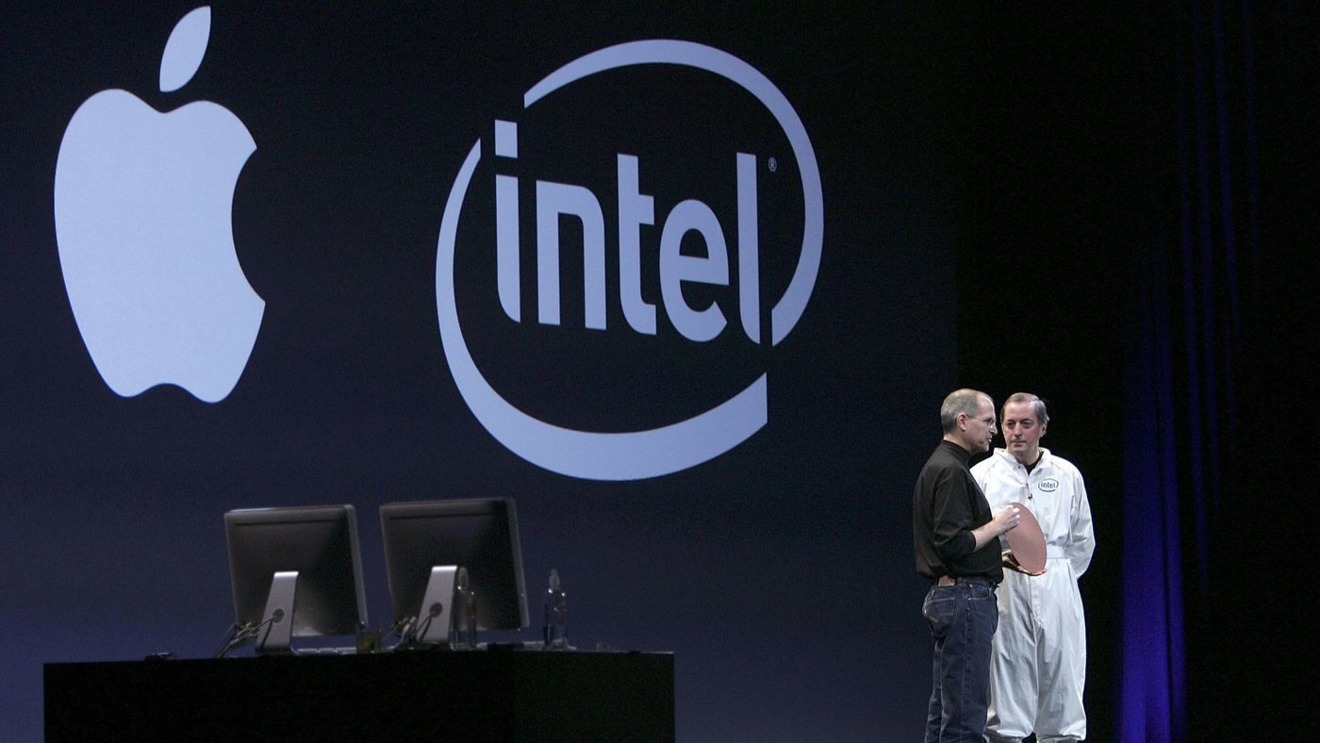

Rumors started in 2002 that Apple had a version of Mac OS X that ran on Intel's processors. These rumors persisted until June 2005, when Jobs announced at the WWDC that just 11 years after the last major hardware shift, new Macs going forward would use Intel processors.

PowerPC-only code ran for a while on Apple's emulation layer called Rosetta. Once again, applications shipped with binaries containing code for both Intel and PowerPC, but this time around, they were called for a brief period of time in the beginning of the shift "Fat binaries" before settling on "universal binaries" for the remainder of the transition.

The first nail in the PowerPC coffin was the release of Snow Leopard. The final was the extermination of Rosetta in MacOS Lion, released on July 20, 2011.

Convincing Mac buyers to buy the iPhone and iPad

Again, after about a year of rumors, Jobs launched the iPhone — the platform that would launch the company into the stratosphere. But, first, it had to convince the long-time Apple faithful, buoyed by the iPod, to buy the device.

Originally based on the OS X Kernel, the diminutive device didn't run any software that ran on the Mac, and still launched the iOS App Store gold rush. Early reviews cited software incompatibility as a weakness, as did some AppleInsider readers — but the phone was solid enough that it didn't matter.

A bit later on, when the pre-iPad rumors started flying about, a common refrain was that it would be a Mac OS X-based device, and run Mac software, and cost about $1000. None of that came to pass, with the iOS-based tablet retailing for $499.

Microsoft tried the same approach with Windows RT on the Surface, but it didn't pan out at all.

The future

The Mac was in the works in varying forms for four years before it launched. The PowerPC shift effort started in 1988 with the "Jaguar" project under Apple executive Jean-Louis Gassee. It ultimately merged with other efforts, and evolved over the next six years into the final product.

Apple had builds of Mac OS X for years before it made the shift to Intel. It also set the table for iOS with Xcode — which is now the primary means of developing for the Mac, iOS, tvOS, and watch OS.

In every shift, including less profound ones like Serial to USB, and USB-A and Thunderbolt 2 to Thunderbolt 3, Apple has provided backwards compatibility when necessary. It has not left a technology to die by the side of the road when something new comes along.

The first two times that the Mac shifted to a new architecture, third-party developers got about six months warning before it started happening — and there were many more viable development environments than we have now. With a simple software update to Xcode, Apple could make its software do most of the heavy lifting here.

There has also been a lot of drama about the lack of BootCamp. For some, probably even most, Mac users, it won't matter one bit.

For the rest, there are two ameliorating factors. The shift won't be immediate, and will likely start on Apple's low-end, like the MacBook and possibly a Mac mini migration. Additionally, Microsoft has Windows on ARM now, with a 32-bit software compatibility layer, so virtualization or even Windows on top of one of these new machines isn't out of the question.

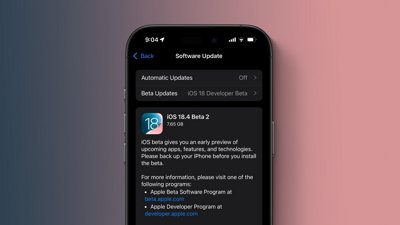

More complaints are swirling about Apple's software. While it is true that Apple could use a little help with quality assurance, users who think that the last version of any Apple software was the best ever have a short memory.

In every operating system Apple has ever shipped, there have been show-stopping bugs. We just have more users beating on Apple's offerings than ever before, so any problems will be found sooner, much like the theoretical infinite monkeys working on typewriters, with one generating the works of Shakespeare given enough time.

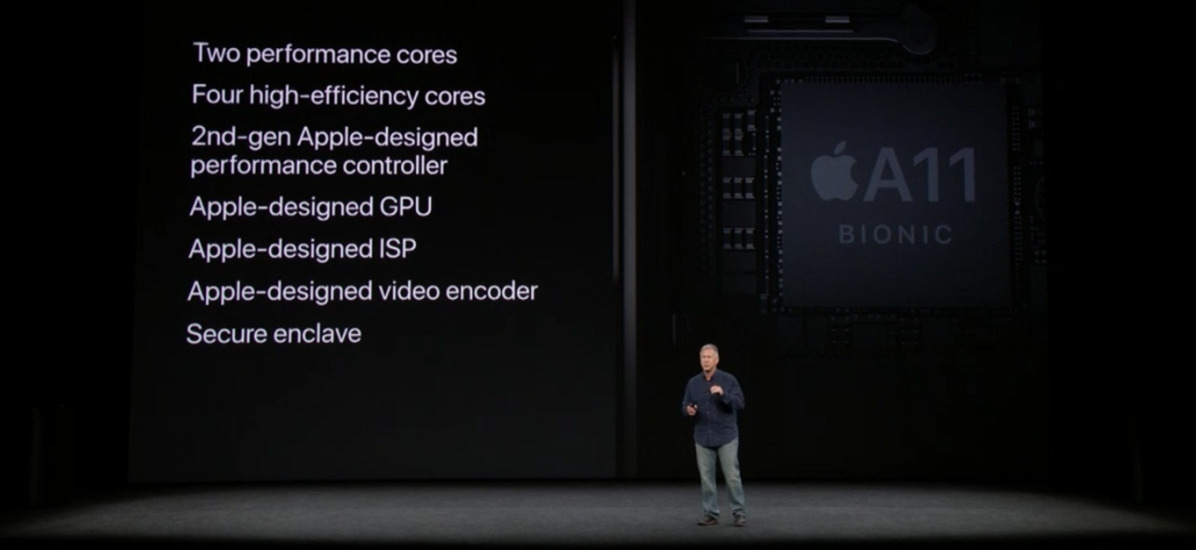

What we'd get with a new Apple-build ARM processor is a new processor architecture not bogged down with literally three decades of legacy routines. We'd get new architecture, with an architecture that can handle LPDD4 RAM, allowing for up to 64 gigabytes of RAM and four times the bandwidth that LPDDR3 and conventional DDR4 can handle.

Yes, we'd lose some devout, like we always have at every shift. But, what the remainders would get is a superior architecture for the future, not beholden to Intel's continued tock, with no signs of a tick that would be beneficial to Mac users coming in a timely fashion.

We've done this as users before. When the dust settles, there will be Intel-devout, when it was talked about as akin to the end of days, the same as the shift to the Mac, and the shift to PowerPC. Plus, your old hardware won't spontaneously combust when the shift is announced, and you can in all likelihood wait until your favorite software is ARM-native to buy new gear.

So, don't fear the shift. There's no need to panic.

Mike Wuerthele

Mike Wuerthele

-m.jpg)

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

Wesley Hilliard

Wesley Hilliard

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

245 Comments

Not panicking at all. I'm eagerly looking forward to this!!!!

Can't wait! people are crazy for panicking with such great news!

Will this be a step towards uniting iOS and OSX?

Is that transition going to be completely seamless and easy? Maybe actually knowing Apple. And if not who cares. How many transitions have we gone through and the complaining has been over the top. iphone. iOS 7 UI, 64-bit CPU’s, Touch ID. Face ID, the iOS control panel animation lol. Battery life for a week, cheaper, faster computers. I’ll take the risk that a couple apps may take a few months to convert over. And if they don’t then I’ll use something else. Let the change of improvement reign