2024: Apple's 40 year old Macintosh survives another year

As 2024 springs into reality, it's a fresh opportunity to look at what Apple can do to to stay alive and remain relevant as its core Mac platform reaches the ripe old age of 40.

If Apple's Macintosh were a person, it would likely be suffering a receding hairline, a stiff neck for no apparent reason, and a troublesome inability to lose weight. It would be finding itself virtually invisible to young people and, at the same time, struggling to remain relevant in the workplace as fresher faced workers run circles around its productivity and demonstrate a leaner, more ambitious drive to remake the world.

Of course, Apple isn't really a person. It's a legal entity that's now made up of over 160,000 people worldwide.

And while its fun to personify the company and even the Macintosh, the reality is that unlike a physical human, the corporation and its core products are actually dynamic ecosystems of activity that can evolve and change and refresh in ways that our far more frail bio-chemical bodies can't.

The Mac's troubled teens

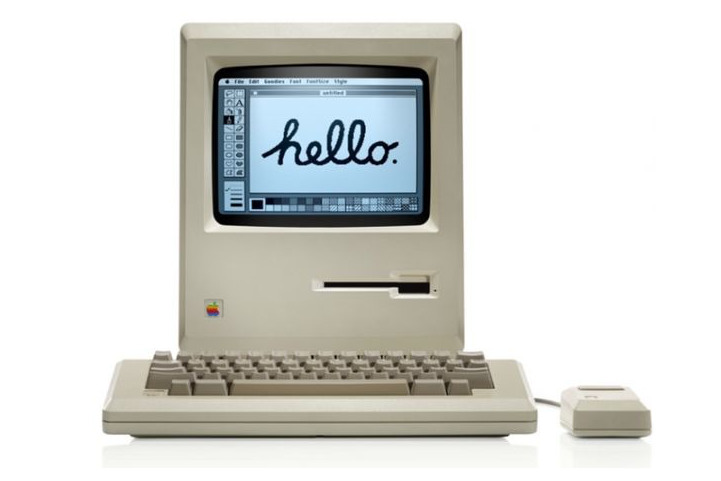

This last year I turned the ripe old age of — gasp — 50! I was barely ten when the Macintosh arrived and changed how we think about personal computing. The original Mac was powered by the 68000, which at the time was an advanced chip developed by Motorola that could for the first time deliver the late 60's pipe dream of graphical computing driven by a mouse, allowing ordinary people to leverage the the power of personal computing with an intuitive Human User Interface that depicted the arcane world of digital files as a virtual desktop with windows and folders of document icons.

The Apple of the late '80s increasingly became a premium priced, marketing-driven company that struggled to compete with generic PC makers that could leverage vast economies of scale. Apple struggled to differentiate itself from these other white boxes. As the Macintosh turned 10, it found itself pitted against Microsoft, its closet software partner. Windows 95 appeared to appropriate virtually all of the core value Apple had created.

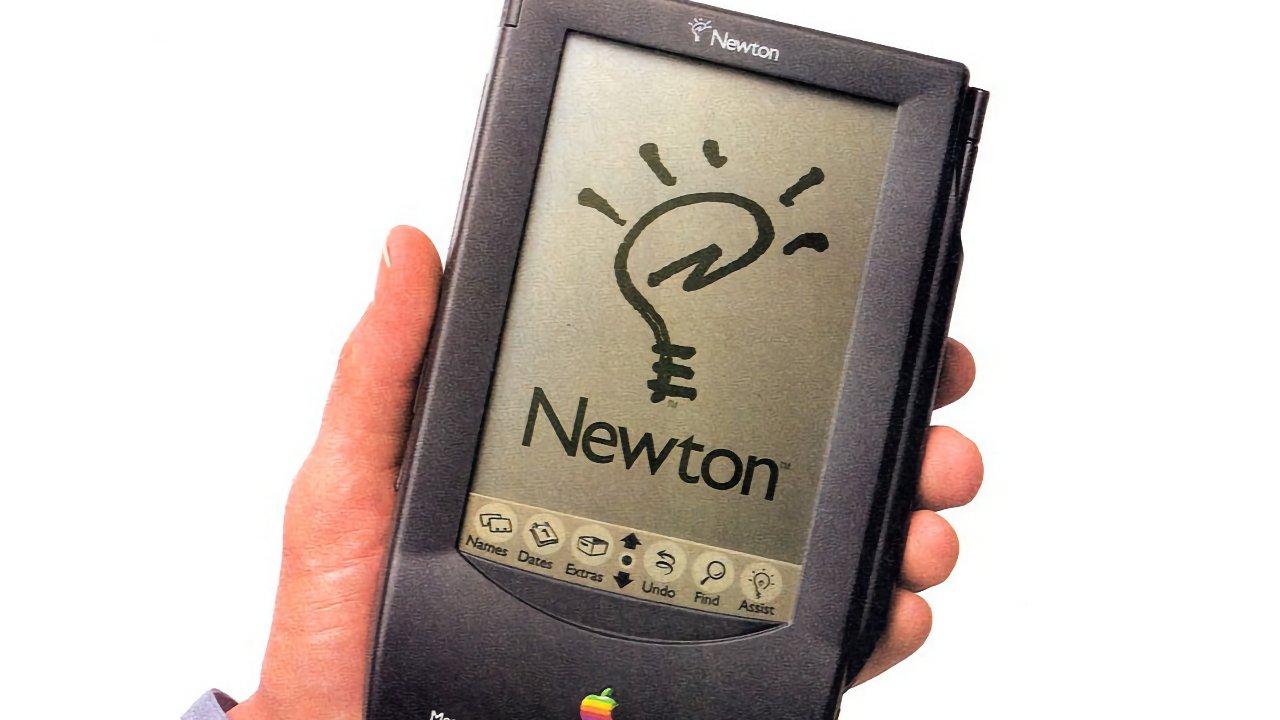

Across the '90s, Apple struggled to find its footing as its Macintosh pursued uncertain markets in hypertext and multimedia. It also struggled to launched its new Newton MessagePad, a handheld computer that was intended to be even easier to use, styled as a "personal digital assistant."

Before the Newton could develop into a useful tool it was undercut by much cheaper alternatives including the Palm Pilot. It didn't help that Newton wasn't really finished and shared little in common with the Mac as a platform in hardware or software.

Apple also tried to introduce digital cameras in partnership with Kodak, and it attempted to find ways to monetize the then-exciting potential of CD-ROM mass storage and the emerging importance of internet connectivity. Apple's pratfalls across that decade relegated it to niche markets and earned it the humiliating badge of being a "beleaguered" dinosaur has-been.

On top of its struggles to identify its next big thing in hardware, Apple was also plagued with core deficiencies in its aging Macintosh system software as well as its software development tools that made a series of backtracking strategic errors.

New Jobs for an old Mac

As luck would have it, the company was saved from oblivion in the late '90s by shaking things up under new management ushered in by Steve Jobs. As the new century started, Jobs' Apple reintroduced the Mac as a more affordable computer oriented towards consumers and prosumers who wanted a simple way to browse the web, do basic desktop work, and organize their digital music and photos.

It was Jobs' Apple that hammered out a new era of exciting potential built upon industry standards, open source code, and perhaps most importantly, a cohesive strategy for delivering constant refinements that delighted the Mac faithful and enticed away Windows users tired of viruses, spyware, incessant adware, and the other perils of PCs.

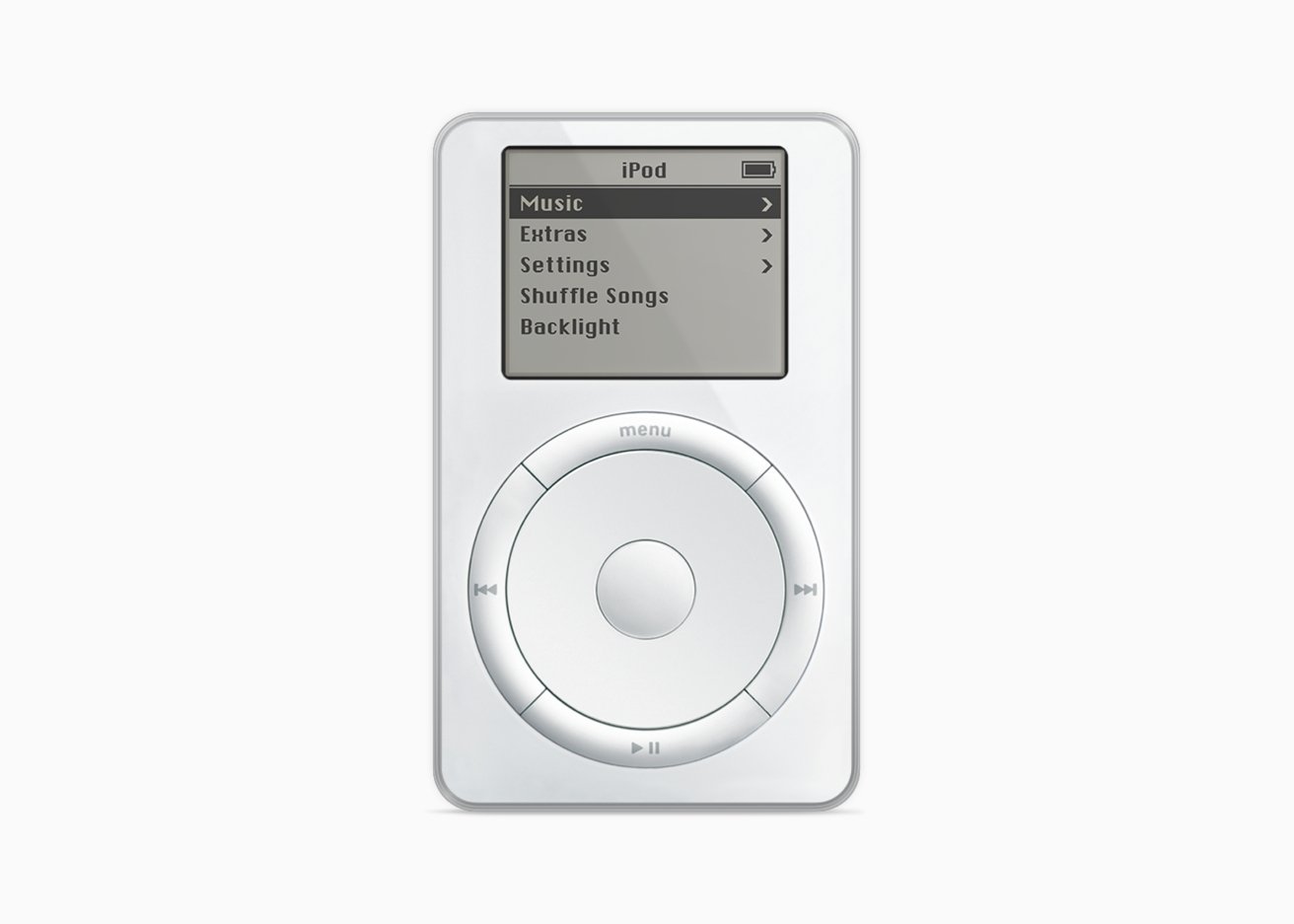

As a young tech professional in the 2000s, I grew enamored with Apple's efforts to deliver products that jettisoned legacy and boldly shifted towards a clean and fresh future where things "just worked" and where new tech products like 2001's iPod and the 2006 Intel-based MacBook felt stylish, solid, fast, and functional in a world dominated by techy complexity often delivered in cheap flimsy packages intended to make their profits from accessory sales and software.

The new Apple was not only cranking out distinctive hardware, but was also delivering fresh annual upgrades to its revamped Mac OS X operating system. I had started writing about Apple and the changes occurring within the company and the overall industry as the 2000s started, with particular attention devoted to the vast disconnect between what Apple was actually building and the narrative of naysayers who frequently assumed that Apple's trajectory would necessarily be undercut and disrupted by others.

Mac life begins at 20

Apple's iPod rapidly grew into a huge business, thanks in large part to the company's new retail stores that aptly demonstrated how much better technology could be if it were delivered as a solution that served customers' needs rather than as a way to benefit media companies. It was this backdrop that enabled Apple to launch iPhone in 2007 as a handheld computing device that could also serve as a cellular phone and work as a familiar iPod.

What was less obvious to many in the tech industry was that iPhone was effectively a scaled down Mac, leveraging its familiar development tools but packaged as a much simpler to use device that didn't need a system administrator to manage. It didn't even need an instruction manual.

It was also less apparent to many tech observers that Apple was devoting monumental efforts to make this possible. In the same way that the company had spent significant efforts to reinvent personal computing with the Mac in the early 80s, iPhone in the early 2000s invested extraordinary work to deliver a complete solution that targeted the pain points of existing mobile devices.

Competing phones, music players, and other gadgets didn't do this, expecting instead to best Apple primarily in pricing with devices that were either much simper phones or more complex and technically encumbered PCs in a smaller package. But thanks to the work Apple had already done to build a mass market consumer electronics business with iPod and a retail powerhouse across hundreds of retail stores that provided support and assistance, iPhone was able to fend off rivals. By 2010, effectively all of Apple's 2006-era competitors in smartphones were suffering an existential crisis.

Apple had turned the tables in the technology world, with the ability to leverage vast economies of scale that enabled it to build faster, more functional and easier to use mobile devices. This also allowed the company to introduce iPad as an alternative way to approach computing in a way that brought the power of desktop computing to a massive new audience.

Alive and adapting

Five years later, it wasn't exactly shocking that the narrative-driven Wall Street Journal was opining that Apple should ditch its venerable Macintosh to focus on the "modern future" represented by its mobile iOS devices. Of course, this idea was absurd because while iPad appealed to new kinds of users with simplified needs, the Mac was still demanded by a growing base of users who required a more powerful desktop.

While Apple was demonstrating a new willingness to allow its product introductions to cannibalize existing markets the way iPod sales were effectively upgraded into iPhones, the company also made strategic efforts to sell its streamlined new tablet alongside conventional Macs as complementary tools. Other companies failed to do this. Android tablets, Google Chromebooks, Linux devices, and Microsoft's various attempts to spawn Windows-based attempts to make "no compromises" by selling one Jack-of-all-trades PC with a stylus or a tablet-like touch screen all failed spectacularly.

Apple entered the 2010s selling not just more individual devices, but essentially different classes of Macs each targeting very clear use cases. Across the last decade, Apple also branched out in selling Apple TV as an even more simplified iOS product that only did a few things, but did those few things really well with effortless simplicity. It also launched Apple Watch as a similarly tiny computer you could wear.

These devices are all specialized branches of the old Macintosh, each paired with a custom interface targeting a unique use case. At every new introduction, Apple's critics boldly claimed that the rest of the world could outpace its development by delivering their own take on tablets, wearables, and various other product categories. They were suckered by pitches that claimed that consumers really wanted something that wasn't a Mac.

Certainly, Apple's expanding array of iOS devices are not sold as "Macs" but they carry forward the same kind of bit mapped display with a powerful platform of software apps, built on the same evolving core. Microsoft once tried to launch its own smartphone without a focus on apps, largely because it couldn't get its developers to make enough.

Amazon tried to promote its concept of "Voice First" Alexa smart speakers because that's what it had spent so much on developing in an attempt to beat Apple and own the future of computing. Google tried to launch Chrome OS and various forms of Android devices that could rival the app platforms of the Mac and iOS App Stores. I no longer have to argue that these efforts aren't good enough.

A future at 40

As the Mac as a platform prepares to blow out the candles of 40 years of birthdays, it has not failed to grow as so many had predicted. It has not merely been eclipsed by modern iOS devices; it has spawned them.

Because they use the same development tools, the dramatically larger base of iOS apps has breathed new life into the Mac. Apple's big investment in developing its own processors not only kept its mobile devices ahead of rivals in past years, but also resulted in the recent convergence of custom Apple Silicon across Macs and iOS, iPad OS, and watchOS devices.

All these years later, Apple continues to market and report device sales separately for its Mac desktops, mobile, tablet, wearable and other new categories. This year, Apple will introduce Vision Pro as another new app platform, custom designed to serve a new solution for immersive computing. It remains to be seen how many units Apple will ship, but in useful terms, the legacy of this new iOS-related device is quite literally another new form factor and implementation of the soul of the Mac.

It's tempting to contrast Apple's developments with Microsoft's one-time goal to bring "Windows everywhere." In reality, that strategy only meant stretching the one computing model it had appropriated in the early 90s from Apple and copy-pasting this windowing desktop model across everything from office copy machines to personal media players and the smartphone. This didn't work out successfully anywhere.

Apple did the work to determine how to bring the utility of the Mac everywhere in a form appropriate to the solution it was creating. Apple Watch, Apple TV, iPhone, iPad, and the upcoming Vision Pro don't share the Mac's look and feel. They share its core functionality, paired with a custom human interface appropriate to their use. In hindsight, that's clearly the right approach.

Apple's prowess in birthing new children to the Mac that don't just lazily replicate and spread its original 1980s interface, but instead develop and adapt to fit new environments and uses demonstrate how important it was for the company to spend exhaustive efforts to study how to create and build new solutions that will appeal to customers. This is a model Apple can keep pursing into the future.

At the same time, the company is also fleshing out new peripheral devices ranging from AirPods to AirTags and HomePods that can provide accessory functions. CarPlay isn't a device but rather another use-appropriate interface driven by your iPhone. Further advances are coming thanks to the shared technology of silicon and software platforms that will continue to add value to the Mac and its progeny.

It's an exciting time to be alive as Apple takes raw technologies and crafts functional solutions from it. So don't sweat the Mac getting middle aged. It looks like it will outlive us all.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

Charles Martin

Charles Martin

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Mike Wuerthele

Mike Wuerthele

Chip Loder

Chip Loder

29 Comments

Excellent perspective. I'm glad to see your articles again!

I’m the same age as the author. It constantly amazes me to think of where Apple is today compared to the 70s-90s. The Apple of our youth was truly an underdog that almost didn’t make it. I bet there are a lot of parallel universes in which they didn’t make it.

I'm about 18 years older than the author. If there are alternative universes, there are likely a few where Xerox went after the mass market, rather than allowing Apple and Microsoft to capitalize on the Xerox Alto graphical user interface. There could be one or two alternative universes where H. P. did not rebuff Job's request to have H. P. build microcomputers for Apple. There could even be an alternative universe where Intel manufactured chips for the iPhone.

If Apple Mac were a person I’d recommend he (she?) move to The Philippines, where age is respected and the weather is warm. Lol

My first Apple product was an Apple ][ with 4K of RAM and basically nothing else which I purchased in 1977. Today I am walking around with an iPhone 15 Pro Max with 8GB of RAM and 512GB of storage. My laptop is a MacBook Pro 16” with 32GB of RAM and 2TB of storage. My phone has 2,000,000 times the RAM of my Apple ][ and my laptop has 8,000,000 times the RAM.