In-depth review: can Amazon's Kindle light a fire under eBooks?

Amazon Kindle

3.0 / 5Amazon's new Kindle ebook reader is billed as the iPod for digital reading. Will it inspire a new era of mainstream electronic reading, just service a dedicated niche of hard core readers, or simply fizzle out into failure? We put the new device through its paces to find out.

The deck isn't stacked in Amazon's favor. Unlike Apple's iPod, which only improved upon the technology and design of music players that already enjoyed an established market, the Kindle attempts to outmaneuver existing ebook devices that have never really achieved mainstream popularity. The Kindle faces the daunting task of cultivating ebook adoption in the scorched soil that failed to yield sustainable growth for earlier ebook vendors over the last decade.

If anyone could make ebooks work, it's likely to be a company like Amazon with the clout and connections to line up content and reach a wide market of avid readers. Last year, Borders, the second largest US book vendor, similarly partnered with Sony to sell its new Reader. Barnes and Noble, the number one bookseller, turned down the offer to participate, telling the Associated Press, "We have sold e-readers before and they haven't done particularly well."

Despite its partnership with Borders, the Sony Reader hasn't been a big hit over the last two years of trying. Unlike Sony, Amazon has no relevant experience in developing and delivering consumer hardware. That makes the Kindle hard to compare against the the success of the iPod, because Apple's improvements over existing music players back in 2001 were largely technology improvements.

Apple used a smaller form factor hard drive to make the iPod more compact than direct rivals and give it more capacity than Flash devices. It chose high speed FireWire to make it sync much faster than USB 1.0 models, and it commissioned an intuitive user interface that made using it simpler. Unlike devices designed by Sony and Microsoft, Apple also made the iPod DRM-optional and allowed users to add their existing music. Apple didn't start offering its own content until 2003.

Amazon's primary value add is in lining up commercial content for the Kindle and delivering it through an innovative partnership using Sprint's cellular network. Amazon also leverages its existing online store to integrate a user's account with the unit, making it easy to find, order, and manage content. Since most users don't already have a library of ebooks waiting to be read, Amazon isn't really following the footsteps of the iPod at all.

Technical Hurdles for eBooks

As with the devices already on the market, the Kindle faces some significant engineering challenges. Readers expect ebook devices to meet or at least approach the experience of reading physical books. That requires a high resolution display that is at least close to the size of a paperback book. However, high resolution LCD screens are expensive and large enough displays to be easily readable eat up power too rapidly.

Those factors force the Kindle to use E Ink, a different display technology that offers high resolution density for sharp text and longer battery life despite its generous 6" display. Everything from the iPod to the iPhone to laptops and flat panel displays use LCDs, which use a matrix of liquid crystals that change shape when electricity is applied. As they change, they form patterns that are nearly invisible, but using a bright backlight, they can be illuminated to create a bright, colorful display.

E Ink works using colored particles. When an electric current is applied, the light and dark particles are aligned into patters that are clearly visible without a backlight. That results in much greater power efficiency, but introduces some limitations of its own. Essentially, an E Ink display is a bit like an electronic Etch-a-Sketch or the magnetic beard of Wolley Willy: it redraws the screen one page at a time as an original creation. E Ink displays can't rapidly update though, resulting in very slow and clumsy animation of the user interface; animation is an important feature in navigation and user feedback to signal progress and changes. In addition, on the Kindle and most other ebook readers, E Ink is limited to four shades of grey.

The result is a sharp, monochrome display that requires ambient light to read but which requires so little power than it can coast for days without recharging. That makes E Ink perhaps the best technology to use as a book replacement. However, the technology also severely limits E Ink's applications outside of acting like a book. The image below contrasts the Kindle's E Ink display against the backlit LCD display of a laptop.

Interface and Navigation

The biggest problem for E Ink is that it can't redraw rapidly enough to support animation such as a mouse cursor or smooth page scrolling. Kindle attempts to work around this limitation using a scroll wheel to navigate between options on the page.

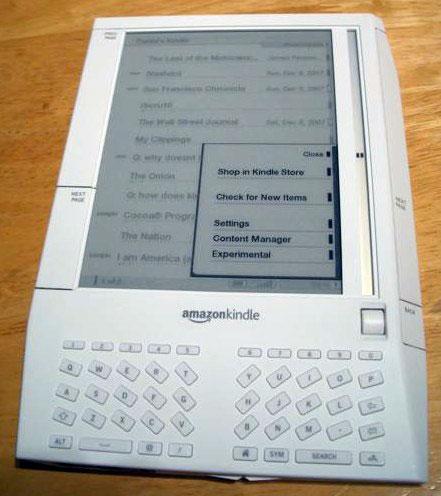

Dialing a small roller up and down animates a silvery block cursor in an independent track that uses its own display that can update rapidly (above). This navigation track allows the user to select between options presented on a page, or to select a line of text which might include multiple hyperlinks within it. Once selected, a push down on the roller brings up a menu, typically including options to:

- select from one of the hyperlinks in the selected line.

- lookup a word in the selected line.

- jump to the Home page.

- visit the Kindle Store shopping page.

- navigate within the existing document to its front page, table of contents, a specific location, a sections listing, or user specified bookmarks.

- add notes to a document, highlight a selection, and access earlier notes.

- create bookmarks.

- save a selected page as a digital text clipping that can be output to a computer.

The right and left edges of the unit each have two large buttons: next and previous page buttons on the left, and next page and "back" buttons on the right. It seems logical that "back" and "previous page" would do the same thing, but that is not always the case. Sometimes back returns to a previous section, for example. It isn't consistent enough to really be intuitive or predictable, however.

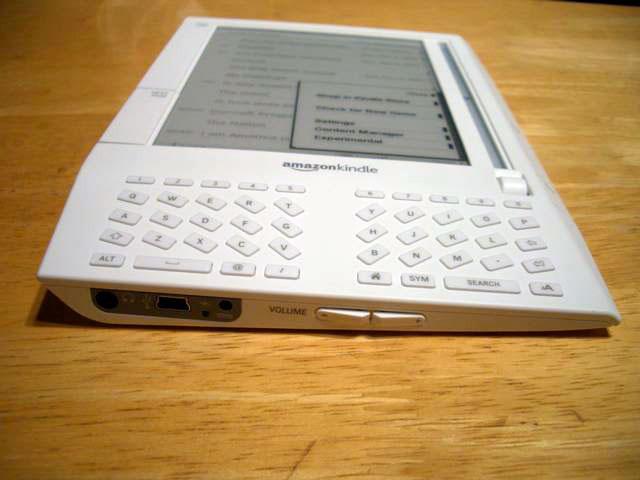

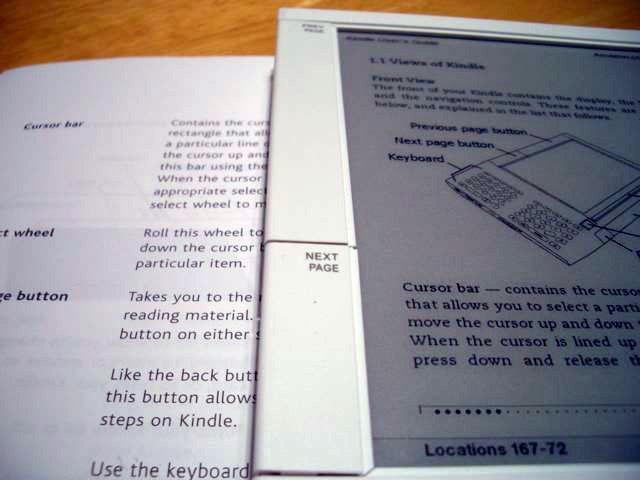

There is also a full keypad below the screen for entering text, along with alt, symbol, and search function keys and a button that brings up a menu to change the text display size used when reading a document. Between the E Ink display and the roller wheel cursor track, it's quite easy and usually intuitive to figure out how to navigate around, but the slow page refresh is a significant problem that severely taxes navigation speed, as every menu presented involves a flash and a pause.

Physical Features

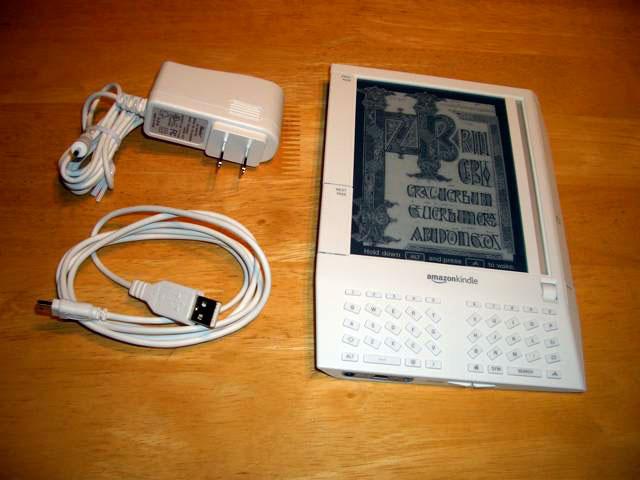

The unit ships with a USB cable and a power adapter (below). The adapter automatically handles worldwide voltage differences, so to use it overseas you only need a physical plug adapter, not a more expensive transformer. The Kindle's cellular wireless features only work in the US, however.

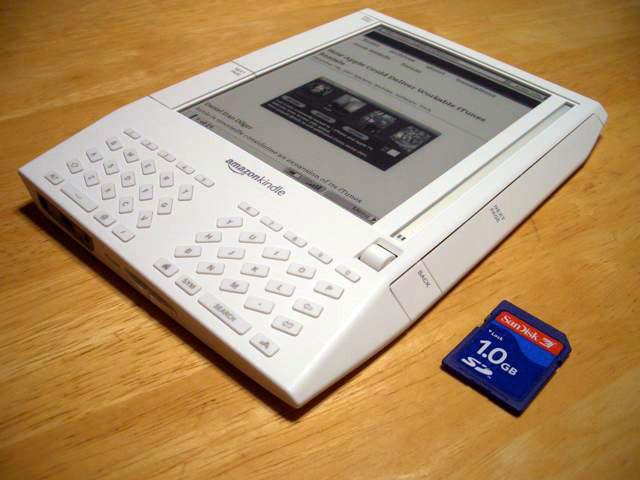

The Kindle itself is oddly wedge shaped. The left edge is 0.7" thick, and slopes down to the right so that even when laying flat, the display is at an odd angle. Apart from the top and bottom edge, every side, surface, and corner of the unit is beveled at odd angles and surface planes. The device looks like a blandly modernist building of the mid 80s trying to stand out solely through quirky, unexpected lines.

It must have been designed by a committee that deliberated long and hard over input from lots of people, because clearly a lot of compromises were brokered, and there's just too many odd mistakes for it to have come from the mind of one lead designer.

On top of its strange shape, the eggshell white plastic unit looks extremely cheap, from its roller navigation control wheel to its chintzy keyboard. The Kindle almost feels purposely cheesy, as if it was designed to look fashionably tacky as a nostalgic nod to early 90s electronics. Within its price target, it blindly blows past any previous example of shoddy looking electronics gear to attain a level of unsophisticated ugliness that would seem difficult to rival.

At the same time, it doesn't really matter that the Kindle's hardware looks silly because it's not designed to show off or admire, but rather to be used. Being sexy or fashionable isn't of prime importance for an ebook reader; looking sharp certainly hasn't helped Sony's Reader, an ultra slim metal tablet that has been largely ignored by the public. The Kindle's cheap white plastic makes it a neutral looking frame for the text you're reading, as opposed to the shiny black or silvery metallic finishes popular on many ebook readers.

The bottom edge of the unit sports volume controls, a power plug adapter, a mini USB port, and a headphone jack (above). Two slider switches on the back turn the unit on and optionally activate its wireless service. A dark grey rubberized cover slides off the back to reveal a standard SD Flash RAM slot for extending memory and a removable battery pack (below).

The odd styling of the Kindle makes it clumsy to hold. I'm right handed, and typically would hold a book in my left hand and turn pages with my right. I instinctively picked up the Kindle with my right hand, but found it extremely unwieldy to hold that way because the center of gravity is on the thicker left side. That forces you to hold it in your left hand. I found the Kindle a bit clumsy to hold every way that I tried; it's also difficult to handle without inadvertently hitting the page turning buttons that make up most of the right and left sides.

On page 2 of 5: Judging the Kindle by its Cover; The Amazon Content Connection; The Depth and Breadth of Amazon Content; and Thinking Outside the Book.

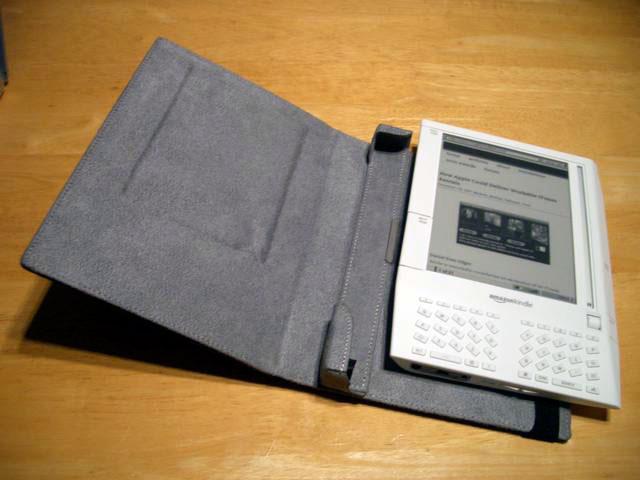

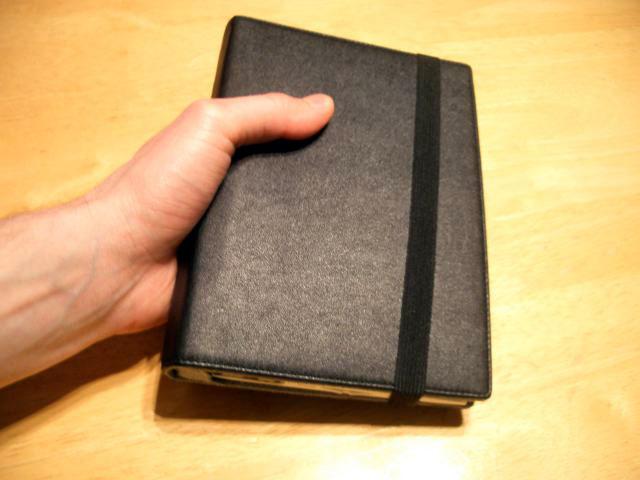

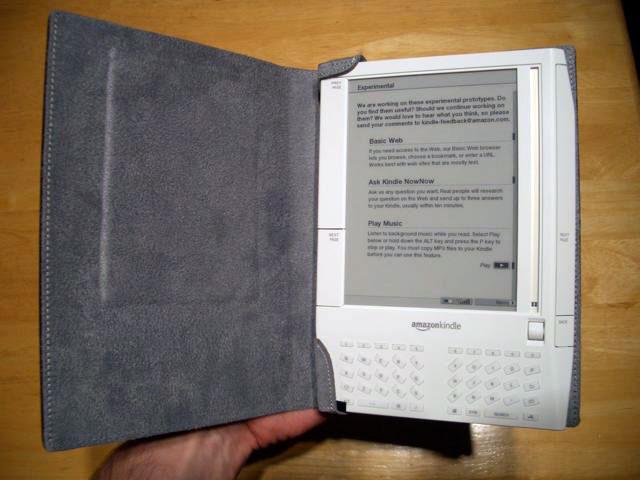

It seems the Kindle was only designed to be used with the included leather cover, which turns it into a hard bound virtual volume. The cover itself seems well built and is more attractive looking than the Kindle itself. It includes a padded area to protect the Kindle's screen (visible below top) and has an elastic band that holds the cover closed when not in use (below bottom).

Snugly fit into the cover, the odd Kindle shape makes more sense. Reading is still a bit foreign, as it feels like you are forever stuck on page one of a hard cover book, but the page turning buttons reflect how you'd turn real pages: tap the right edge to page forward or reach over to touch the upper left to flip back. Kept inside the cover, the Kindle quickly begins to feel natural, although it can still be easy to bump the page turning buttons accidentally.

Being inside the cover doesn't make the keyboard fell any less cheap, but the Kindle is designed primarily to read information, not to enter significant amounts of text. Taking the Kindle outside of its cover is a bit like taking a snail out of its shell: it lethally converts its plucky, slow crawl into an ugly mess you don't want to have in your hands. Used as intended however, the Kindle seems to work well within its intended purpose as an electronic reader.

Reading Between the Lines

Because the screen isn't backlit, you can't read in the dark. In bright light, the Kindle's display looks like very much like light grey, unbleached paper printed with a good quality inkjet printer (below, in contrast with paper). In dim light where paper books are still very readable, the Kindle's contrast and readability falls dramatically; it's like reading a wet newspaper: black on dark grey.

That limitation comes with the territory for devices using E Ink. The upside is that the Kindle lasts forever on a battery charge. It's rated for two days of use with the wireless antenna turned on, and a week if you turn it off. The wireless service, called "Whispernet," is used to order and receive content, and can also be used to access Wikipedia and experimentally browse the web. The store and ebook download service is exceptional, but the other online features sound more attractive than they actually are.

For a number of obvious reasons, directly competing against paper with a digital reader is quite impossibly difficult. For the serious reader, Kindle offers a variety of very compelling features that weigh against the inherent limitations of replacing paper with electronics. In sufficient light, the Kindle is about easy to read as paper; unlike the printed page however, you can select from six levels of type size on the Kindle, which range from what looks like a compact but readable 12 point type to a large, oversized 24 point font. That makes it an enabling technology for readers who require larger type.

Being digital also means that the Kindle can hold scores of volumes and periodicals without consuming space or filling landfills. Once fitted into the cover, it generally works well enough to serve as a stand in for a real book and makes it possible to read text-oriented books, magazines, and newspapers without waiting for or paying for shipping, and without unfolding a tabloid or broadsheet paper.

The Amazon Content Connection

The main reason this oddly shaped plastic gadget absolutely wipes the floor with Sony's sharper looking Reader is that fresh content for the Kindle is literally a few clicks away. Unlike the iPod or iPhone, you don't need a PC or or any software equivalent to iTunes in order to use the Kindle, although it does include a USB cable that allows you to manually drag files to the device as if it were a Flash memory card.

There's also that standard SD Flash RAM slot on the back that can be used to store additional document files on the device, or to manually transfer content from another system. Plugging the Kindle into a Mac or PC via USB presents both the internal Flash and the SD card as mounted volumes. It does not however provide any access to its internal system software, which happens to run a version of Linux, just like Sony's Reader. Incidentally, running Linux doesn't necessarily mean the device is functionally open; there is not currently any way to extend its features. Additionally, all Kindle purchased content is protected by DRM.

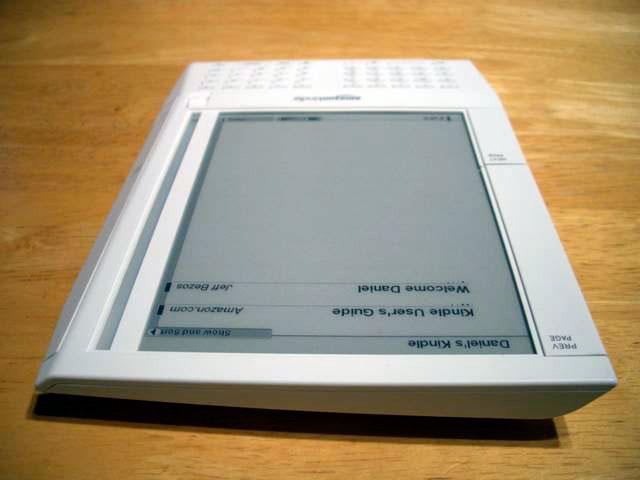

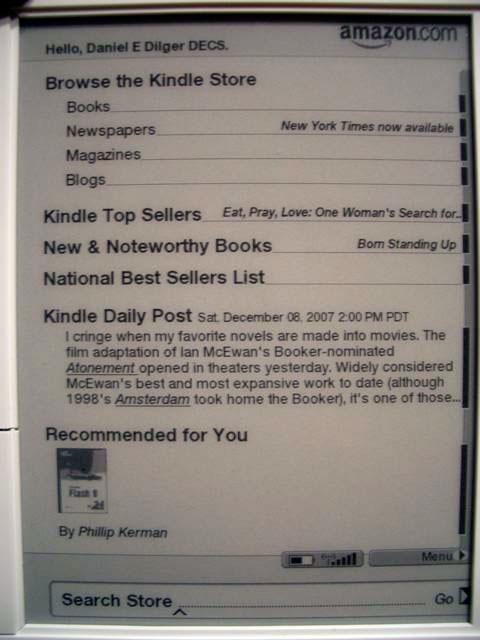

The exceptional new wrinkle introduced by the Kindle is its wireless features. Amazon links the unit to your account before mailing it to you, so it shows up personalized with your name when you turn it on. Amazon also activates EVDO mobile data service for you, which is included in the price of the unit and the content you buy. EVDO is the 3G mobile data service offered by CDMA2000 providers such as Sprint and Verizon Wireless, as opposed to the GSM network providers AT&T and T-Mobile in the US. EVDO is also what wags have in mind when they complain about the iPhone's mobile data service not being 3G. As described in How AT&T Picked Up the iPhone: A Brief History of Mobiles, EVDO is significantly faster than AT&T's "2.5G" EDGE, but is much slower than WiFi.

The Depth and Breadth of Amazon Content

Since the digital books and periodicals Amazon delivers are all relatively small, EVDO is plenty fast enough to download content. It typically arrives before you can actually navigate back to the home page to look for it. Issues of the Wall Street Journal appeared to be about 500 - 700 KB, and books seemed to be on average about the same size as long as they didn't include illustrations.

In the 180 MB of free space available, Amazon estimates you can hold about 200 books. If you need more than that, you can drop in a cheap 1 GB SD card and carry around a thousand more books. That type of capacity offers digital book readers another major reason to take the plunge. But where does one get it, and how much does it cost?

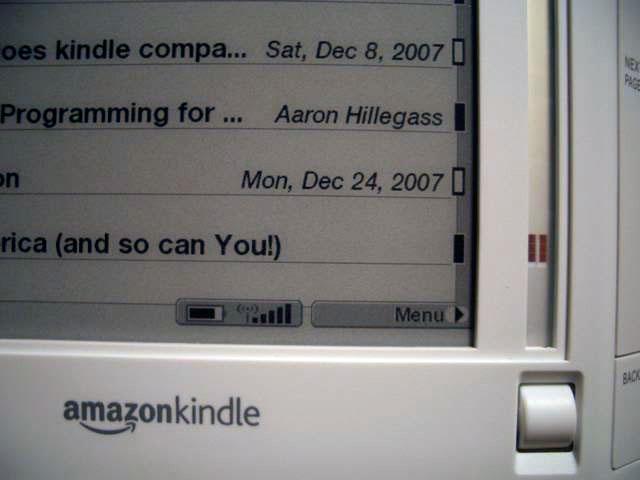

Books from the Amazon store (above) cost around $10 for bestsellers and new releases, or a couple dollars for public domain books. Other books are discounted significantly from list prices. For example, Aaron Hillegass' "Cocoa Programming for Mac OS X" lists for $44.99, but is offered at $29.96 as the Kindle download. The paper version is listed on Amazon's website at $31.49. Oddly, Amazon listed the full "print list price" as $49.99 on the web, suggesting a greater discount percentage online despite actually being cheaper as a download.

You can download a sample of a book for free to try it out; I sampled Hillegass' Cocoa book, which included the first three chapters, roughly 10% of the entire book. If you buy a book on accident, you can immediately undo your purchase. You can't sell or giveaway your ebooks when you're finished with them, as they are tied to your account just as most iTunes media downloads are. Rather than paying for a paper copy of a work that wouldn't be easy to duplicate, you're licensing a digital copy that— without DRM— would be trivially easy to mass duplicate and distribute.

The Kindle store lists around 94,000 titles broken down into two dozen categories. Those titles will likely expand rapidly as Amazon continues to line up new content. That sounds like a lot of books, but there's still significant gaps caused by publishers leery of entering the ebook business, and there were a number of duplications. For example, under "Computers and Internet," the store listed nearly 5000 books, but two of the top ten were "iPod and iTunes for Dummies," the latest version and an old edition from 2004. I find it difficult to believe that many people are actually buying a three year old edition of a "how to" book that was published prior to 90% of the iPods ever sold.

The Kindle ebook selection looks more like what Amazon could quickly wrangle the digital rights to distribute, not necessarily a listing of the most popular or most significant books. There were no Harry Potter books, but there were eleven books explaining, attacking, or defending the Harry Potter books. On the other hand, there are five books by Ann Coulter, who has only written six, and at least one of them was filed under the reference section. The Kindle catalog and selection needs some work, but it's still impressive that it's already both larger and lower priced than Sony's "thousands" of Connect ebooks and Mobipockets' library of 40,000 ebooks.

Thinking Outside the Book

Amazon is also offering the Digital Text Platform, which allows writers to publish and sell their work as ebooks for a retail price between a quarter and $200. Amazon pays the author 35% of the proceeds based on the price set by the author. That move makes for an interesting addition to Amazon's existing retail business, and a new opportunity for self-published works.

The Kindle store also offers digital editions of daily newspapers that range from $6 to $15 per month, with a current selection of just 8 US papers: the Wall Street Journal, New York Times, San Jose Mercury News, San Francisco Chronicle, Investor's Business Daily, Seattle Times, and Atlanta Journal-Constitution, as well as the Irish Times, the French language Le Monde, and German Frankfurter Allgemeine.

There's also a selection of digital versions of magazines at $1.25 to $3.50 per month. Currently, the offerings are limited to the Atlantic, Time, Fortune, Forbes, Readers Digest "express", the Nation, Slate, and Salon. Each issue feels a bit abbreviated, but there's also no advertising, so it makes for dense reading.

On page 3 of 5: Other Alternative Content: Blogs, Audiobooks, and Other Documents; A Decade of eBook Failure; Amazon Kindle vs Amazon Mobipocket; Kindle eBook Content Management vs Sony Reader, iTunes; and Kindle vs the iPhone or iPod Touch as a Document Reader.

For a couple dollars a month, you can also subscribe to one of 310 different blogs. Some of these blog options make more sense than others. For example, one option is Slashdot, which is primarily valuable for its user comments, not its half dozen paragraph synopses posted every day. If you subscribe to it, you end up having to follow its links into the Kindle web browser to read either the originally linked story or the comments.

Other blogs have longer text entries that might make more sense to subscribe to, but the Kindle also allows you to directly access the web for free, so it seems hard to understand why you'd pay to subscribe to blogs unless the web browser version of a site just didn't work well on the Kindle browser. Reading blogs through the subscription service is nearly as slow as navigating the web. In fact, any time you venture outside of text-centric book reading, the limitations of the Kindle immediately begin to punch you in the face. As long as your primary use of the Kindle sticks to reading longer passages of text, the Kindle is rather friendly. Amazon's broad portfolio of books and periodicals is a good start to keep you happily occupied with reading.

It's also possible to manually copy over plain text files and unencrypted Mobipocket books, Audible audiobooks (formats 2, 3, and 4, which are the same are those sold in iTunes), and MP3s. Amazon also offers an automated email service for converting HTML or Word documents into the Kindle format, as well as for graphic files such as JPEG, GIF, PNG, and BMP. It will either mail them back to you for free to manually upload using your computer and the included USB cable, or wirelessly send them to the Kindle directly for a ten cent delivery fee.

A Decade of eBook Failure

Amazon's Kindle rollout suggests that the company just invented the ebook. In reality, the concept had already danced into the public consciousness several in the last decade. Each time, rivals dramatically fought over the stage and then walked out mid-performance after finding lackluster participation from the audience.

Back in 2000, the French Mobipocket introduced an ebook format and subsequently rolled out Mobipocket Reader software for a wide number of handheld PDAs including Palm, Pocket PC/Windows Mobile, and a various other smartphones.

The same year, Microsoft introduced Microsoft Reader for its WinCE-based Pocket PC, and later followed with support for Windows tablet PCs and UMPC devices. Like its other efforts, it was centered around tying an emerging industry to Windows; it introduced a new proprietary ebook format, loosely based on Microsoft's HTML Help format.

In contrast to the DRM efforts to sell ebooks commercially, Project Gutenberg began working to release plain text versions of the world's books. The group's efforts accelerated after setting up a non-profit organization in 2000, and it has collected and published over 22,000 ebooks to date. However, Project Gutenberg formats its texts using a hard returns to wrap text every 65-70 characters, rather than letting it flow an be resized by the reader. That nearly ensures that its ebooks won't look good on any handheld ebook reader, and won't support alternative text sizes very well.

By 2005, Microsoft had lost its interest in the ebook business after it became clear there was no easy money in selling them, and that there was no credible demand for WinCE-based, LCD devices as ebook readers. Mobipocket had also found tepid interest in commercial ebooks, but it worked to stoke interest by offering free downloads of public domain books. Unlike Project Gutenberg, Mobipockt's format allows text to flow and be resized.

Amazon bought Mobipocket in 2005. Although it never began selling Mobipocket books through its online store, it did brand Mobipocket's website with the Amazon logo and continued the practice of offering free reader software for Windows, Palm, Windows Mobile, Nokia and UIQ Symbian phones, Blackberry, and other hardware. It does not provide any Mac support however.

After the first wave of ebooks crashed, Sony floated a new ebook reader in the Japanese market called the LIBRIé in 2004. It followed up with the 2006 introduction of the Sony Reader for the US market. The Reader lacks the keyboard of the original Japanese version, so there's no support for adding notes. Like other Sony hardware, it was tied to the Windows-only Sony Connect store for content, which was oriented around Sony's own BBeB proprietary format. As was the case with Sony's ATRAC audio players, those factors helped to assure that the Reader would never take off.

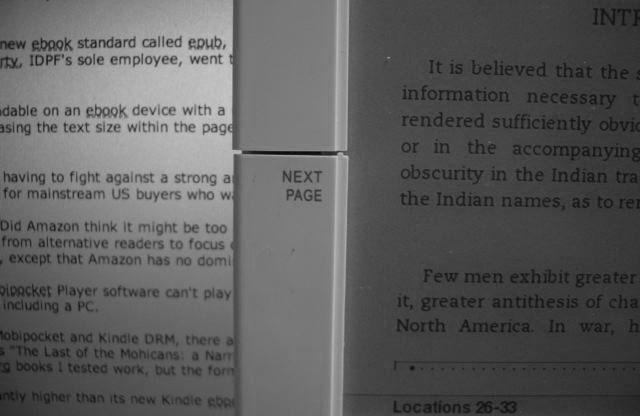

Earlier this year, the officious sounding International Digital Publishing Forum announced a new ebook standard called epub, which included support for PDF. The IDPF had a single employee and a single gold sponsor: Adobe. Following the announcement, Nick Bogarty, IDPF's sole employee, went to work for Adobe, which now markets epub support in InDesign and other Adobe products.

Because most PDFs are formatted for a letter sized document, they often aren't readily readable on an ebook device with a 6" monochrome E Ink display that can't support real time zoom. PDF is also a presentation format, not a content-oriented format, so increasing the text size within the page isn't among its strengths either.

Amazon Kindle vs Amazon Mobipocket

That history leaves the Kindle facing little effective competition in hardware and free from having to fight against a dominant rival offering a strong and entrenched ebook format. Combined with Amazon's popular online book business, it appears that the Kindle is the only viable option for mainstream US buyers who want to read commercial ebooks.

It is also interesting that the Kindle wasn't integrated into Amazon's Mobipocket business. Did Amazon think it might be too complex to market its own hardware while also servicing reader software for other platforms, or did it just want to syphon attention away from alternative readers to focus on Kindle? Either way, the situation looks a lot like Microsoft's rival and intentionally incompatible ventures with PlaysForSure and Zune DRM, except that Amazon has no dominant ebook rival like iTunes to battle against.

To clarify: Amazon's Kindle can't use Amazon's Mobipocket DRM books, and Amazon's Mobipocket Player software can't play the new Kindle DRM books. Amazon also does not offer any reader software that allows Kindle books to be used with any other devices, including a PC.

Amazon doesn't seem to make much mention of it, but despite the odd chasm between Mobipocket and Kindle DRM, there are 10,000 free English Mobipocket, public domain, DRM-free books that do work fine on the Kindle. I downloaded James Fenimore's "The Last of the Mohicans: a Narrative of 1757" from Mobipocket and had no problems copying the file to the unit and reading it in various text sizes. Project Gutenberg books I tested technically work, but the formatting is terrible at any text size because of the fixed line length.

Amazon's existing, commercial Mobipocket ebook offerings are commonly priced significantly higher than its new Kindle ebooks. The same Cocoa book noted earlier at $31.50 at Amazon and $30 on Kindle is a full $49.99 for the Mobipocket version. One reason Amazon introduced a new format for the Kindle might likely relate to distribution contracts and Amazon's desire to offer Kindle books at a more attractive price than earlier ebook ventures and their publisher agreements accommodated.

Kindle eBook Content Management vs Sony Reader, iTunes

Despite its cheaper looking hardware, the Kindle functionally matches the technology of Sony's competing Reader and raises the stakes with an integrated wireless distribution service tied to a larger and easier to use library of commercial ebooks.

Sony requires Windows-only Connect software to download content to the Reader. It uses Sony's own BBeB DRM format for ebooks, but also directly supports text, RTF, and PDF documents on the Reader, and includes a converter to save Word documents as RTF. It also directly supports standard graphic formats and plays both MP3 and AAC audio, but has no support for Audible audiobook DRM like the Kindle. Sony's Connect store also offers 20 blog RSS feeds, but lacks the ability to update feeds directly.

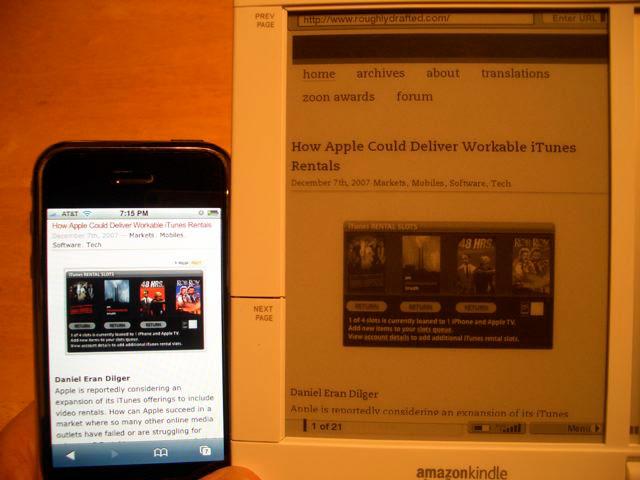

Rather than offering desktop software to manage the Kindle comparable to Sony's Connect or Apple's iTunes, Amazon has tied the Kindle to its online service in a way that doesn't require the user to even own a PC. This is an interesting strategy, and makes sense for Amazon because its user base already has online accounts with the company. Rather than interacting with desktop software, the Kindle acts as a wireless thin client to Amazon's web store, similar to the new WiFi iTunes Store on the iPhone and iPod Touch.

Among other things, this frees Amazon from having to develop client side software of any kind. That explains why it offers an email conversion service rather than a conversion utility, and also allows Amazon to support users of any operating system: Mac, Linux, or even users without a PC.

The Kindle's Whispernet service makes ordering new content easy, and delivers fresh content fast. Amazon links and archives everything you purchase against your Amazon account, so even if you delete ebooks from your device, you can download them again from Amazon. That's more convenient than iTunes, which only allows you to download purchased content again if you call in and plead a hard luck story.

The underlying reason for the difference is that Amazon's $10 digital books are around 1MB or less, making them about a third the size of iTunes' 99 cent songs, or roughly 1/300 the size of iTunes' $2 TV half hour episodes, or a thousandth the size of a $10 hour long iTunes movie download. Amazon doesn't have to deliver nearly as much data as Apple every time users want to download their entire purchased library over again. From that perspective, Amazon's ebook content is small enough to not require a more sophisticated desktop application.

Kindle vs the iPhone or iPod Touch as a Document Reader

Apple hasn't signaled any intention of entering the ebook market, although it does sell audiobooks in iTunes. It has the ability to sell PDFs from the iTunes Store, but currently isn't selling any outside of offering free digital booklets with certain album downloads, distributing PDFs alongside other content in iTunes U, or within its iTunes Apple Developer Connection. There's certainly no technical barrier that prevents Apple from flipping a switch and offering a library of digital books.

Unlike typical ebook readers using E Ink displays, the LCD display of Apple's iPhone and iPod Touch can zoom in and out of documents, skirting the limitations of PDF or heavily formatted Word documents that commonly confound Kindle and the Sony Reader. The iPhone can also handle other documents, from Excel files to full color graphics and fluid video.

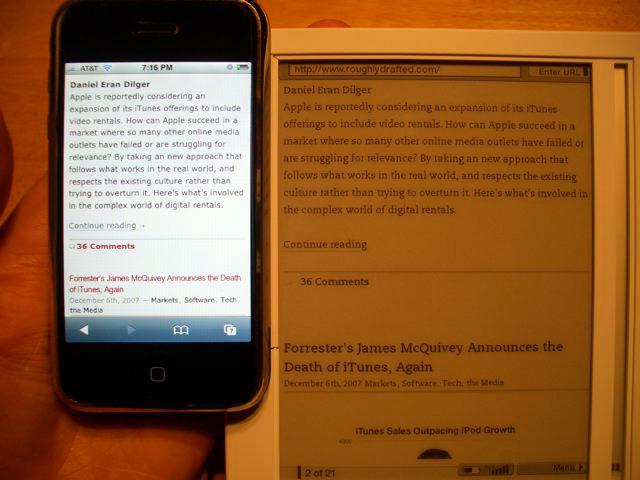

While the iPhone's display is significantly smaller— about half the visual area of the Kindle and roughly a quarter the resolution (320x480 vs. 600x800)— it's just as sharp (160 pixels per inch vs the Kindle's 167 ppi), it's backlit for reading in the dark, it's full color, and most importantly it has no slow refresh cycle. The downside is that the iPhone doesn't last nearly as long on a charge, particularly if you're actively using it to read documents or browse the web.

Despite the larger screen size and resolution of the Kindle, both show about the same amount of content, even when the iPhone is zoomed in for reading text and the Kindle is set at its smallest text size to show the most content possible (below). The Kindle can only show a small set view of the page, while the iPhone can zoom out to see the entire page overall.

Few people will find themselves trying to decide between the Kindle and the iPhone, because they are very different products. However, many will ask themselves whether the Kindle's E Ink advantage of reading for a week without power makes it worth considering on top of their existing mobile phone or media player. At $400, the Kindle is a significant investment in reading, and the small discount offered on many Kindle digital books certainly doesn't outweigh the upfront cost of the unit. The Kindle is a premium service compared to buying paper books, but does end up being a bit cheaper than most other ebook offerings.

For readers who consume books and want to sample from a fair selection of regular new content, the Kindle is a great match. For users who want to occasionally take digital copies documents with them but get most of their information from online sources, the Kindle is far behind the iPhone or iPod Touch, which make it so much faster to navigate between and within documents that the speed advantage of the Kindle's 3G EVDO is easily wiped away by the half as fast EDGE or embarrassed by the far faster WiFi when a hotspot is available.

Of course, the other key feature of the Kindle is its walled garden of content. While you can read online newspapers and other content on the iPhone via Safari at no additional fee over your existing mobile data plan, you can't currently download ebooks and magazines apart from ebooks offered in plain text or PDF. That won't change until Apple either wades into the ebook market in iTunes, third party developers offer Mobipocket or Kindle DRM for the iPhone, or Amazon opens its Kindle format up for other devices. If Amazon can sell its Kindle hardware profitably, the latter is unlikely to happen.

On page 4 of 5: Audible DRM Support; Kindle MP3 Playback; Amazon vs Open Formats; Kindle Readability; A Real Page Turner; and The Kindle's Experimental Periphery: iPhone Territory.

While the Kindle advertises support for Audible audiobooks, it requires a PC to handle the Audible DRM; you have to download Audible's Windows-only AudibleManager software to authorize your Kindle before using it with Audible content. Once that happens, you can then copy over your audiobooks purchased from iTunes or elsewhere and play them.

Since Amazon advertises Audible support, it should offer an authorization feature within the unit itself so users don't have to do that step manually. Apple's iTunes invisibly handles this step for users of iPods and the iPhone.

The Kindle might serve as an occasional audiobook player, but it makes no sense to use it primarily as an audiobook device. The iPod Nano, outlined in Winter 2007 Buyer’s Guide: Microsoft Zune 8 vs iPod Nano, costs half as much and is nearly invisible compared to the diary-sized Kindle. It also holds 4 or 8 GB of audio, rather than less than a quarter GB of Flash RAM on the Kindle.

A two hour audiobook file is about 30 MB, and a full book such as John Hodgman's "The Areas of My Expertise," involves three files. That means two full audio books could easily wipe out the entire capacity of the Kindle. Using the SD slot, you can add more capacity, but doing so wouldn't make the Kindle a cost effective or reasonably sized device for listening to audiobooks.

Kindle MP3 Playback

On the subject of audio, while the Kindle includes a tiny speaker on the back of the unit and supports headphones, it doesn't offer much for sound quality. If you like to listen to fair quality audio while you read, it's there, but don't expect much from it as an audio player.

It currently only supports MP3 files that you manually copy over via USB, and again, it only ships with 180 MB of free space. It also only plays back songs in random order. There's no playback controls and no way to select a specific song to listen to while you read something else. The Kindle also can't yet play back standard MPEG AAC, the format iTunes uses to rip CDs by default; the Sony Reader and other modern audio players can. If you use iTunes, as most people who use audio on computers do, you might find that you don't have as many MP3s as you might think.

I did a search on my laptop for an MP3 to test, and all Spotlight unearthed was a bizarre test file hidden in "ringtone samples" that shipped with Adobe GoLive CS2. It sounded like Erasure yodeling. Please don't look this file up, and certainly don't play it on your system, or you'll be scarred for days with the kind of terminally catchy, candy bells CGI sound that is so hard to purge from playing inside your head once you've heard it. You have been warned.

In any event, the Kindle's inability to play AAC means you might not have much music to copy to it unless you purposely transcode it back to the older MP3 format. Inability to play AAC is probably not a huge problem for the Kindle, as its not much of an audio player anyway. The fact that Amazon has launched a parallel effort in selling DRM-free audio in the old MP3 format might also play into why Kindle doesn't support the newer and less restricted AAC format.

Amazon vs Open Formats

Amazon seems to be intentionally limiting the Kindle from playing back popular open formats— including PDF, rich text, and AAC music and podcasts— that might compete against what it hopes to sell to Kindle users itself. These limitations might be explained away as efforts to ship the Kindle; Amazon might likely expand the supported file types in the future.

Nobody should expect the Kindle to play back rival DRM-encrypted ebook formats from Sony, Microsoft, and Adobe, but it is bizarre that Amazon isn't even supporting its own Mobipocket DRM format, which works on various other systems. That sure makes it look like Amazon hopes to own a closed system for ebooks that prevents users from using Kindle DRM files anywhere else but the Kindle itself.

In addition to the Mobipocket Reader software for PDAs and smartphones, there is also a variety of competing ebook devices that handle commercial content in the Mobipocket DRM format. By not supporting this on the Kindle, Amazon is signaling what appears to be an intent to abandon existing Mobipocket devices such as the Bookeen Cybook and the iLiad, made by Philips spinoff iRex.

Imagine if Apple had— after establishing iTunes in the market— released the iPod as a new device didn't play either MP3 or FairPlay music sold in the iTunes Store, but rather introduced a new format that could only play on the iPod itself, and expected everyone to repurchase their music in FairPlay II. This would have resulted in a blogger Armageddon. It will be interesting to see if Amazon licenses its new Kindle DRM format for use on these other systems, which largely serve markets outside the US. Regional book licensing agreements may also play a factor in complicating how Amazon can distribute its ebooks. Kindle sales are currently limited to the US, just as Apple's iTunes sales were at its launch.

The situation with Amazon differs from iTunes in that Apple is primarily a hardware company; it opened the iTunes Store in order to ensure that commercial content would remain available for the iPod at a time when Microsoft posed an overwhelming threat to competition in media with PlaysForSure and Windows Media, as described in Universal vs Apple in the iTunes Store Contracts. Amazon is the direct opposite: a content retailer entering the hardware business in order to drive sales of its content in a way that existing hardware makers can't compete against or participate in.

Kindle Readability

Realistically, most users in the Kindle's target audience won't be fretting over open standards and interoperability, but will look primarily at whether the ebook reader works as advertised. Is the Kindle practical as a reading device? It certainly is, but how useable it is depends a lot upon what you want to use it for.

Like a diesel engine, the E Ink technology in the Kindle is best suited to readers who want to plow through long hauls of sustained reading. Reading full length books are its strongest point, magazines are also quite practical, but newspaper articles lie on the edge of suitability. The more you plan to read content out of order, skip between sections, and scan over short articles, the less practical the Kindle becomes, largely because of the slow display technology. Each page turn on any E Ink system involves a brief flash that repaints the display. If you're reading a book, this pause isn't any more of a problem than flipping a page, and feels quite natural after a while.

However, while I like the idea of reading newspapers digitally rather than waiting for the delivery of a dead tree version, the Kindle rapidly bogs down when reading news. Its navigation design is about as good as once could hope for, but the page turning delay at every navigation, every skip, and every skim over a headline and section can quickly become frustratingly slow.

A Real Page Turner

It's also too easy to go back when you intended to go forward, as a Next Page button lies along most of the right edge, and also along the lower left edge. The Previous Page button is on the top left. The Back button on the lower right commonly goes back a page as well, unless the context suggests to go back some other way, which is often the case (back to a previous heading, for example). This cross positioning of the hair trigger page buttons frequently led to my hitting the wrong thing, either by targeting the wrong one by mistake, or accidently bumping an edge when i had no plans to leave the current page at all.

The result is a pause and an unexpected page turn, which requires first deducing which direction you actually went and then deciding how to get back to where you intended to be. When that happens, the page flash refresh pause is far more distracting, particularly if you hit the wrong button again. There's no animation suggesting which way the page turned, so its easy to get lost as to what's happening when a page refreshes unexpectedly.

The Kindle also redraws the page twice in a row on occasion, with a delay between the two. This happens in particular when loading graphics; one refresh gives you the text, a second redraws the page with full graphics. When that happens, its easy to be left wondering if you're still on the correct page or if you've accidently triggered a page turn and need to be somewhere else.

The Kindle's Experimental Periphery: iPhone Territory

Once you stop reading long passages and begin skipping through content and rapidly navigating around, you reach the line between where the Kindle falls apart and the iPhone takes off. While the Kindle offers a longer battery life and a larger reading area more suited to extended reading sessions, the iPhone's direct contact interface, immediate zoom and instant scrolling simply leaves the Kindle gasping to keep up in tasks outside of the Kindle's dedicated reading niche.

If you want to read books and periodicals straight through, the Kindle should suit you well. If you want to browse newspapers and use the web, Kindle's E Ink technology makes it at best a third rate alternative; it works acceptably in a pinch if you're reading long passages of text on the web, but it is nearly worthless for general purpose web browsing, despite its fast 3G Internet connection. Unlike a PC browser, the weakest link for the Kindle isn't connection speed but its slow display, which makes navigation a delicate affair that can be undone with a single accidental tap on the Back button.

Sometimes, back means go back a page; other times it returns you to the main menu, which is particularly annoying if you are in a web page. It forces you to navigate to the Experimental menu, look up the web site, and then find your place again, with each step plagued by a series of slow page turns. This kind of thing makes using the Kindle web browser about as frustratingly challenging as building a house of cards on a lazy susan in a small room with a kitten and a puppy, during an earthquake.

It also highlights why Apple didn't wait for 3G data service on the iPhone. Browsing the web using EDGE on the iPhone is faster, more efficient, and far more enjoyable than the 3G Kindle, simply because the iPhone's Safari web browser is speedy and so much easier to use. EVDO also has a dramatic impact on battery life, sucking down a week's worth of battery life in less than two days, whether you're actively using wireless services or not.

In Kindle's Advanced mode of the web browser, the page layout of a variety of common websites— including Wikipedia, oddly enough— is rendered unusable because many sites assume users have at least a 1024x768 display. On those sites, text wraps beyond the edge of the screen, and there's no way to scroll over horizontally to read it. Switching into Basic web mode (which is the default), I could at least read the full text of Wikipedia, blogs, and other sites, although the formatting was scraped away in a way that was distracting. Common punctuation was missing, including dashes and quotation marks, and subheadings that were supposed to be in bold were not. The inability to scroll while browsing the web is a major handicap. Looking at the web one page screen at a time feels like a trip back to 1995, browsing the web via Lynx on a command line terminal.

As noted above in the comparison to reading documents on a device like the iPhone, despite having less resolution than the Kindle, the iPhone easily shows more content on the screen in its web browser (below, with the Kindle browser in Advanced mode). Its Safari web browser can pan around or zoom out to view the entire page as it was intended for a larger screen. The Kindle is set frozen in a 800x600 page view with one font of text, no ability to scroll horizontally, and can only navigate one page at a time vertically.

The default font size for the web browser is set by default in the middle (setting 3 of 6), which roughly matches the smallest size (setting 1 of 6) of text when reading ebooks (which is the default setting for documents). While you can adjust the web browser font smaller than 3, doing so makes the text on most websites illegible. At setting 1, the letters are about the same size as the iPhone when zoomed in to a similar scale (above), but kerning and letter forms on the Kindle degrade rapidly at small sizes in the browser, either because of inherent limitations of the E Ink display or Kindle's limited font smoothing software. Which ever is the case, it makes the first two size settings impractical. When reading ebooks, all of the text sizes are very readable.

Another problem with the Kindle browser is that graphics can frequently fall on the edge of two rendered pages, making them difficult to view. There's no way to repaginate the web on the Kindle apart from fiddling with the text size, which involves three slow page redraws as you navigate through the text size menus. The four shades of grey also leave a lot to be desired when viewing the web.

The limited nature of the web experience explains why Amazon charges a nominal monthly fee for "reading blogs," a service that delivers content from a variety of internet sites in a format similar to a periodical. While you can enter the Experimental menu and try out the web browser for free, some might want to pay to not have to struggle with the troublesome browser. Realistically, as long as the Kindle uses an E Ink display, web browsing is not going to improve dramatically. Most of the painful experience of web browsing relates directly to the screen technology, and there's little Amazon can do to dramatically improve things with software browser improvements.

On page 5 of 5: Also Filed Under Experimental: NowNow; A Calamitous Keyboard; Searching for the Words; Room for Improvement; Love It and Hate It; Will the Kindle Catch Fire?; and Rating.

The Kindle's limited MP3 playback features are also filed under the Experimental menu, along with an answer service that sends automated search results to natural language questions you enter. Called NowNow, the free service gives you "up to three" answers to questions you type, "usually within ten minutes."

No, the three answers aren't yes, no, and maybe. I asked it "how does the Kindle compare with Sony Reader" and received three replies within a couple minutes, two of which cited Gizmodo blog postings, and a third referenced an enthusiastic endorsement of the Kindle by another blogger who gushed about its advertised features but admitted she hadn't actually received it yet. Somewhat ironically, she also apologetically praised its unrealized potential by noting that "future versions show promise (much like the Zune)."

Unlike the Zune, the Kindle is actually a pretty good product right now for the role it was intended, and Amazon has carefully danced around all of the pitfalls described in Why Microsoft’s Zune is Still Failing. It compares well against leading ebook readers, doesn't push expiring DRM subscriptions, and offers wireless features that sap the battery but actually do very useful things. While it's not sharp looking, the Kindle is at least functional and makes the most of its limited scope technologies.

NowNow also asked me to rate the answers it sent me as great, good, insufficient, or junk ("off topic or inappropriate"). I also received the answers from NowNow on my computer via email. Of the other questions I asked, some answers sounded like customer support replies based on bulletin board posts based on Wikipedia articles based on blog entries: informal, unauthoritative, and representative of the fact that a lot of people have spare time on their hands to copy and paste text around. Is Amazon harnessing this idle volunteer workforce, or just faking it with smart algorithms? It wasn't obvious whether NowNow is completely automated, tied into Amazon's Mechanical Turk, run by dedicated staff, or some hybrid of all those things.

Amazon has been working to muscle its way into search since starting the A9.com search engine several years ago. Through early 2006, A9 had been powered by Google. Amazon then partnered with Microsoft's Live search. Late last year, A9 downsized and discontinued more of its services. Curiously, when I asked A9 the same question I'd asked NowNow, I got entirely different answers, and Gizmodo wasn't even in the top ten.

When I asked A9 about NowNow I found out that Amazon also offers the same NowNow service online, although it is currently limited to a private beta. It appears that NowNow may eventually replace Amazon's marginal A9 search efforts. NowNow is currently only available to the general public from the Kindle.

A Calamitous Keyboard

Typing in queries brings us to the Kindle keyboard. It has the same "real" mini keys that smartphone pundits like to recommend over the iPhone's touch interface, although the Kindle keys have more spacing and are larger and easier to hit than most mobiles' keyboards. The keys themselves cover an area about as large as the iPhone's screen itself. The keyboard is extremely horrible to a degree that's hard to overstate.

Entering long passages of text isn't a strong point of the iPhone either, but it easily outclasses any text input features of the Kindle. This tends to make any Kindle features that require any text entry borderline impractical. While it's easy to select pages as clippings or bookmark them, don't expect to enjoy annotating passages in your ebooks. Entering text on the Kindle is about as silly as editing Office documents on a tiny key cell phone without a touchscreen.

Sony's Reader dropped its keyboard for the US market, apparently assuming that text notations were impractical for ebook reader users. While it's really not very practical to type in notes, it is important to have some mechanism for entering text, even if the keyboard is absolutely dreadful to use. Amplifying the really bad physical design of the Kindle keyboard is the slow display, which can't refresh fast enough to keep up with even the slowest typing.

That makes it impossible to see what's begin entered as you enter text quickly, and by "quickly" I mean getting in four characters between the slow page redraws. The keys themselves are fiddly chicklet things that require a significant press and make a plastic snap sound as you hit them. It's an experience comparable to clacking out text with an tape label embosser. Don't expect to be writing emails, entering web comments, or jotting significant notes in your books. They keyboard is really that bad.

Searching for the Words

The keyboard does comes in handy for entering short bits of text, such as when searching local content, searching the online store, asking short questions of NowNow, or searching Wikipedia. That last feature, which is a free part of the Kindle package, is slightly more useful than general web browsing, but is still hampered by the single page navigation limitations of the display.

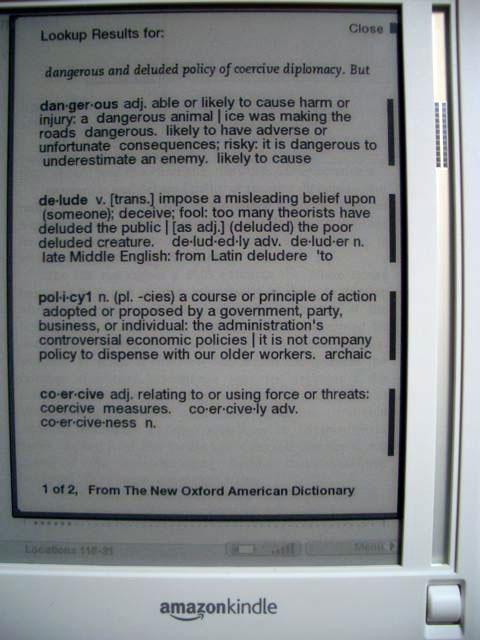

Another built in search feature that can be handy is the lookup of dictionary definitions for words in any text. From any document, you can select a line of text using the scroll wheel navigation track and then chose Lookup from the menu that appears. You are presented with definitions for every major word on that line (below). This works pretty well, although again it involves a series of slow page turning delays. At least it doesn't require using the keyboard.

Room for Improvement

It's useful to look at the Kindle as more than just an oddly shaped, awkwardly designed bit of hardware. It's also a limited use, specialized computer so Amazon will be able to roll out software updates that offer additional features. One thing that would be nice is built in activation for Audible DRM, even if the Kindle isn't that ideal of an Audible client. Amazon could also add the ability to order other items from its online store.

Amazon won't be able to significantly improve upon its slow E Ink display or tragic keyboard with software updates, but expect the company to revisit the Kindle design in a year or so with better hardware features: a less worthless keyboard would be nice, a faster display might make a slight improvement, and a more attractive form factor would broaden its appeal.

Don't dream that a dedicated E Ink book reader like the Kindle will make a good web browser any time in the next several years, however. E Ink technology isn't really morphing towards an LCD replacement, but instead is getting thinner and more flexible. Refresh update speeds are getting better, but it would have to dramatically improve in order to edge around the problems plaguing the Kindle's web browser.

Beyond the Kindle unit itself, there's a huge amount of promise associated with Amazon's overall strategy to make content available digitally, particularly if Amazon opens up its ebook format to work on other devices. As a content retailer, Amazon seems better suited to selling content that works anywhere rather than trying to exclusively push its own hardware. Amazon isn't Apple; it's making money on content. Establishing a common ebook format would likely sell content faster than limiting it exclusively to a junior engineered reader unit. For that reason, its puzzling why Amazon didn't simply repurpose its existing Mobipocket format.

Love It and Hate It

Unlike a lot of other consumer electronics devices, the Kindle isn't a love it or hate it device; it's a bit of both. The Kindle's E Ink display, which is nearly identical to every other ebook reader because there's only one company that manufacturers them, is both efficiently readable and frustratingly slow. It makes it possible to closely emulate the printed page, but at the same time also hampers the unit's potential as a web client or really anything else but a dedicated ebook reader.

Amazon couldn't do a lot toward improving the ebook experience with hardware technology, so it tied in its real expertise: an online retail store that serves up fresh content. Next to the iPhone, that makes the Kindle among the first practical applications of the networked thin client devices that were talked about a decade ago but didn't immediately materialize. It's also a harbinger of other devices that make use of the existing mobile data networks without requiring an expensive contract.

How is it that Sprint is agreeing to offer data service for the Kindle without the typical $40 EVDO data service contract typically required of smartphones? Well for one thing, the Kindle is slow enough that users couldn't possibly drag down any significant amount of web traffic even if they tried. There's no way to tether the device to relay its EVDO data connection to a computer (although that would make an excellent hack). It appears Amazon pays Sprint a commission on content sales, allowing Sprint to make enough to cover the trivial amount of data traffic the Kindle generates.

The hardware itself is cheap and plasticky to the point of being embarrassing to use. It's not so bad hidden away inside the leather cover, but the spectacularly bad keyboard still pokes you in the eye every time you have to enter any text. The limitations of the slow display also painfully yank out your hair with every menu navigation. Bring up a menu and the display slowly repaints a selection of options (below). Pick one and there's another slow refresh of another menu, ad nauseam.

Fortunately, as long as you contain yourself to reading longer passages of text, those glaring flaws fade into the background. Inside the cover, the Kindle does a pretty good imitation of an actual book, and page turns are reasonable enough once you learn to ignore the screen flash. The ability to carry hundreds of books digitally and request new content wirelessly both offer compelling reasons to sign up with the Kindle.

Content seems reasonably priced, particularly since it is both conveniently delivered and backed up for you on the Amazon site in your account. Text searching, word lookup, bookmarks, highlighting, and clippings are all additional good reasons to consider going digital.

There are also some very significant drawbacks. Text annotations are no match for scribbling notes in a book; even if you can bring yourself to type out a note of consequence using the deplorable keyboard, you're still less likely to remember your notes, and you won't be able to mark up a quick doodle in the margin. Its clumsy note taking features makes it very unlikely that— as many pundits have suggested— students will somehow be able to give up their backpack of heavy books for a Kindle anytime soon. Even worse, few of those textbooks are likely to be available in Kindle format.

Will the Kindle Catch Fire?

While the innovative and seemingly well executed Whispernet service is a key feature of the Kindle, don't expect it to serve as a PC or iPhone replacement for browsing the web. It's handy that you can access Wikipedia and web sources from the experimental web browser at all times, but it has nothing on a real web browser with an LCD display that can zoom and scroll and quickly navigate around the page and across pages. The Kindle is a book reader with some other things tacked on, and the closer you stick to reading, the less frustrating your experience will be.

If you love books, the Kindle offers a great way to pack around lots of virtual content and grab new content on an impulse buy. At $400, it's not inexpensive, but it's comparable to other ebook readers that don't offer wireless shopping and downloads. The digital books and periodicals Amazon offers are also significantly more affordable than most ebooks that have been offered before, including Amazon's own Mobipocket catalog. That might play into why Amazon created a new format for the Kindle: to leverage publishers into providing cheaper content using some hype and marketing to generate a larger ebook market than has ever existed before. In that sense, the Kindle strategy does have some similarity with Apple's iTunes Store.

Amazon has a lot riding on the Kindle and is heavily marketing it on its website. Even if the new ebook reader doesn't burn down the house with an iPhone-like fervor among book readers, the Kindle plays into Amazon's retail business strategies in a way that makes it appear very unlikely that Amazon will drop ongoing future development due to an immediate lack of interest. That's a key advantage over Microsoft and Sony, neither of which has made anything from their ebook efforts. Amazon has very little to lose in marketing a digital expansion of its book selling business, and can afford to sustain a progressive rollout over several years.

Rating: 3 of 5

Pros

- Highly legible text

- Long battery life

- Exceptional wireless store for content

- Fair prices for most content

- Good selection for an ebook store

- Experimental web features can be handy in a pinch

- No extra data plan required

- Roller wheel navigation mitigates slow display updates

- Included cover hides most of Kindle's ugly bits

- Works with lots of free, unprotected Mobipocket ebooks

Cons

- Very slow E Ink display makes navigation clumsy and slow

- Cheaply designed keyboard makes text entry unpleasant

- Won't work with Amazon's own Mobipocket DRM ebooks

- Doesn't directly support PDF, AAC, rich text, or graphics without conversion

- Thickish, junior engineered device feels and looks cheap

- Experimental web browsing features have been oversold

- Extremely limited audio playback features

- Requires Windows for Audible authorization

High-quality unboxing photos:

High-quality unboxing photos - AppleInsider.com

Where to buy:

Amazon Kindle - Amazon.com $399

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

Chip Loder

Chip Loder

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

Marko Zivkovic

Marko Zivkovic

David Schloss

David Schloss

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

William Gallagher

William Gallagher