Inside Apple's new Mac mini Server

The new Mac mini server offering isn't just optimized to run Mac OS X Snow Leopard Server, but now actually comes bundled with Apple's server operating system software. Previously, home and small business users who wanted to try Snow Leopard Server needed to shell out $500 for the retail box version or opt for an Xserve bundle, which starts at $3000 and requires either a server rack or a sizably awkward 17"x30" of free space.

Prior to Snow Leopard, the unlimited user version of Mac OS X Server cost $999; that's what the unlimited user version now costs with the Mac mini server thrown in for free. The server version of the new Mac mini drops the optical drive to make room for two 500GB, 5400 RPM 2.5" (laptop style) SATA hard drives. It also supplies a capable 2.53GHz Core 2 Duo processor and 4GB of fast 1066 MHz DDR3 RAM (expandable to 8GB). This is all fit into the same 6.5" square, 2" high Mac mini enclosure, which weighs in at just 2.9 pounds.

Compared to the conventional, high end model of the revamped Mac mini lineup, you get three times the disk storage (without a built-in optical drive) for just $200 more. So essentially, Apple is now giving away Snow Leopard Server in the Mac mini server bundle just as the company always has on the Xserve. For the first time ever, this provides Apple with an entry-level server to position at the home server niche and relatively sizable small business market.

Mac vs generic PC in the mini server category

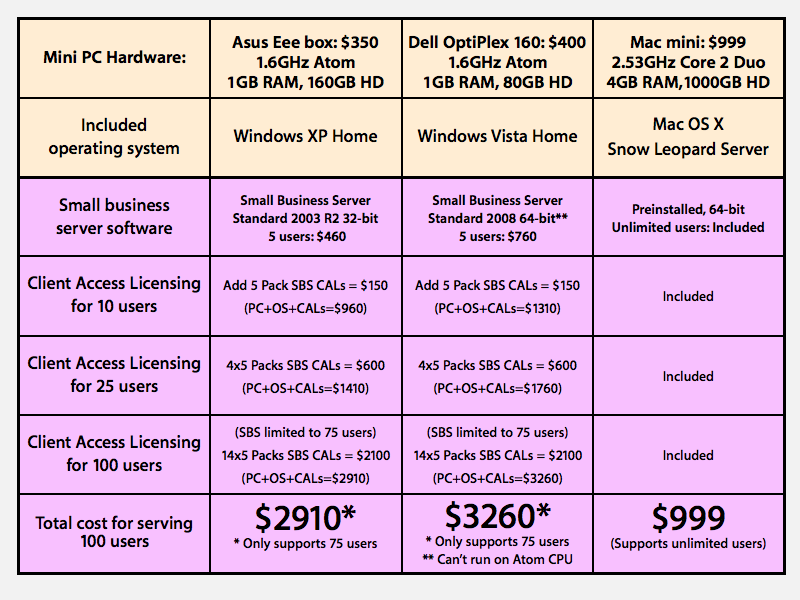

Compared to other small form factor PC servers, the Mac mini server supplies a far more powerful processor than the low-powered Atom or Celeron found in many mini computers such as the $350 Asus Eee Box (which is not sold as a server nor really designed to perform like one). That machine also supplies slower DDR2 RAM, lacks the Mac mini's FireWire 800 for fast external expansion, and hard drives top out at 180 GB.

Most importantly however, low cost small PCs typically ship with Windows XP Home in order to cut costs. That means to do "server" things, you'll have to spend at least $460 on Amazon's "Microsoft Small Business Server Standard 2003 R2 32-bit for System Builders," which includes a five user license. Licensing for additional users costs between $50 to $60 each, or can be purchased in blocks of five for $150.

Small Business Server Standard combines a copy of Windows Server 2003 with a version of Exchange Server (for calendaring, contacts and email messaging); Microsoft's Internet Information Services (web server); Windows SharePoint Services (for collaboration); Routing and Remote Access Service (for dialup access, VPN, routing, and NAT services); Windows Server Update Services (for update management across the network); and a fax server.

Microsoft's "Small Business" bundle is designed to serve small office needs without encroaching on the company's larger server business, where it makes its money. For this reason, the Small Business bundle is restricted in various ways. You can only run one instance of it on the same domain (so you can't buy and set up multiple Small Business Servers to run on the same network); it's limited from joining other domains (such as your larger corporate directories); it can only support a maximum of 75 users; and some features are artificially limited in various ways, such as the Exchange database being fixed to no larger than 18GB. That means if you have 20 users, each person's mailbox and calendar would have to be less than 1GB. The 2003 version is also limited to running 32-bit apps only and to using 4GB of RAM.

If you opt for the latest 2008 version of Small Business Server Standard, you have to shell out at least $760 for the first five users, but it allows you to run 64-bit apps and use up to 64GB RAM. Of course, all 64-bit editions of Windows require 64-bit hardware, so SBS 2008 won't run on a low end Atom, Celeron, or Core Duo processors used in most small form factor PCs.

SBS 2008 still imposes the same bundle restrictions however (along with some new ones, such as not being able to use it directly connected to the Internet as a router without an external firewall), so for unlimited, unrestricted use you'd need the full version of Windows Server, Exchange, and SharePoint, which immediately prices you out of the mini server category, as even the licensing for five users begins at a steep $5,900 and quickly inches up to $20,000 for a single server supporting 100 users.

In comparison, the version of Mac OS X Snow Leopard Server bundled on the Mac mini is the same as you'd get at retail or on an Xserve. Like Microsoft's Small Business Server package, Snow Leopard Server bundles both core server features (DNS, DHCP, directory services, and file and print sharing services with support for Macs, Windows, and other Unix/Linux clients); calendar, chat and email services (with mobile push messaging and calendaring support); web and web-based wiki, blog, and calendar collaboration features; routing, firewall, RADIUS, and VPN services; and client machine backups, software update, and group policy management features.

Mac OS X Server also supplies some unique features of its own, including Podcast Producer for automating video editing workflows from capture to delivery; Xgrid distributed processing; QuickTime Streaming Server for broadcasting media streams; and NetBoot/NetInstall for supporting diskless workstations and remote imaging client machines. The product is not restricted to a certain number of users, and any number of Mac mini servers can be set up on the same network, participate in any number of directory domains, and services can consume as much disk space as the hardware allows. Key services are also 64-bit across the board in Snow Leopard Server.

In contrast, Microsoft's lower cost appliance offering, called Windows Home Server, only offers basic file, web, backup, and media streaming services, not all the things a small office user would want to do.

On page 2 of 3: Apple's fledgling small server business.

Clearly, in the small server business Apple can offer something it doesn't offer in the desktop PC market: a huge price advantage on top of its reputation for premium hardware and sophisticated software integration. Still to be determined is whether Apple can convince home users that they need a server, and that they should pay $999 to get one.

Aside from its core customer base of individuals, Apple is also targeting the Mac mini server version at small businesses, most of whom won't need much convincing that they need a server, nor will have much resistance to paying $999 for a solution that makes setting up their workgroup services easy. As noted previously, there isn't much available between the more expensive Windows Server offerings of Microsoft, very basic file sever and media streaming appliances (often referred to as Network Attached Storage), and DIY solutions that necessitate significant Linux savvy to deliver features approaching those of Mac OS X Server.

To reach business users, Apple has to sell companies on ease of use, reliability, and support. Unlike most generic PC vendors with a significant server business such as Dell or HP, Apple does not really offer any suitable support options that larger businesses demand, such as same day or next day service contracts. However, by packaging its server product with low end hardware, Apple may be able to pick off lots of low hanging fruit in small office or home office settings where users are willing to handle their own support.

Making servers simple

Apple's entire business with Mac OS X was to take Unix and make it friendly and usable by mere mortals. Accomplishing this on the consumer desktop certainly wasn't easy (witness the issues with Linux on the desktop), but it was relatively straightforward compared to trying to do the same in a server offering.

The server space is more challenging to productize in the same way because it's harder to pare down what "most people" want to do and then target 80% of those common tasks with simple solutions. Many users who recognize a need for a server outline custom requirements for themselves and subsequently craft specialized systems tuned specifically to solve their needs. This has resulted in lots of popularity for Linux, which provides nearly infinite customizability, but hasn't worked spectacularly for Apple's "one size fits most" philosophy in selling Mac servers.

Apple is not the first company to try to greatly simplify server tools. In large measure, Microsoft introduced the first mainstream server products with push button simplicity in Windows NT, which borrowed its heavy dependance upon a graphical interface and its self-tuning design from the Macintosh. It wouldn't even be much of a stretch to say that Microsoft in the 90s delivered the server product Apple never quite managed to get right during the 80s.

Unix system admins of the previous decade, commonly looked down upon Windows NT as simplistic and unreliable. However, for entry level users who cared more about solving a task than impressing gurus with their command line savvy, Windows NT provided an approachable, understandable foundation for solving information technology needs in small and medium sized businesses.

As Microsoft began to force its way into the server market in the late 90s, it was able to incrementally improve its server offerings and add new functionality to the point where by the end of the 90s, the company and its offerings began to be recognized as credible and legitimate in certain markets. Today, Microsoft's $14.1 billion annual server business is just a hair smaller than its Windows client sales ($14.7 billion) and growing faster than its relatively flat Office sales ($18.8 billion). In terms of operating profits, Microsoft's server group brought in $5.3 billion, compared to $10.8 billion for Windows and $12.1 for Office. That indicates that the server market overall isn't quite as close to printing money as Microsoft's top two segments, but that there's still lots of money to go after in that market.

In like Microsoft

Like Microsoft a decade ago, Apple is working to expand its desktop offerings into the server arena while working against resistance from established platforms and users that aren't quite sure whether to take the company seriously yet. Working in Apple's favor is the fact that the foundation of Mac OS X Server is quite familiar to Unix and Linux experts, and that existing software, including almost all open source packages, are relatively easy to port over to Apple's platform. This is particularly the case in 64-bit computing, where Apple used the same model as Sun Solaris and Linux rather than Windows Server's unique 64-bit model. It also helps that Apple has now certified Snow Leopard Server as being fully Unix compliant.

Apple does appear to share one of Microsoft's biggest challenges: how to sell server software to market that has an abundance of free alternatives. Among Linux vendors and system integrators such as Novell, RedHat, and IBM, money is typically earned for providing expert help in getting Linux to work as desired. This works out as a key advantage for Apple, which doesn't primarily sell software directly like Microsoft, but rather uses its software savvy to add value to its hardware sales. From this perspective, Apple is a Unix integrator rather than a server software vendor.

Until now, Mac OS X Server has been reserved for customers willing to spend around $3000 to $6000 on an Xserve or pay $1000 to upgrade an existing Mac. But with Apple now selling Snow Leopard Server for $500 and bundling it on the new $999 Mac Mini, the company's server offerings will both receive a lot more scrutiny as a small business appliance option and test out the company's resolve to invest long term in the server market.

Opportunity rings

In the company's favor is the fact that lots of businesses are evaluating the iPhone. In Apple's most recent earnings conference call, Chief Operations Officer Tim Cook reported that "employee demand for iPhone in the corporate environment is very strong. Since the launch of the iPhone 3GS, which coupled with the software made a number of improvements that CIOs were looking for, the iPhone is either being deployed or being piloted in well over 50% of the Fortune 100, and from an international point of view, if you look at Europe, this is true in about 50% of the Financial Times 100."

Cook added that "another very key market for us that some people call enterprise is that over 350 higher ed institutions have approved iPhone for their faculty, staff and students, and in addition to both of these, we continue to be very happy with our sales in the government arena."

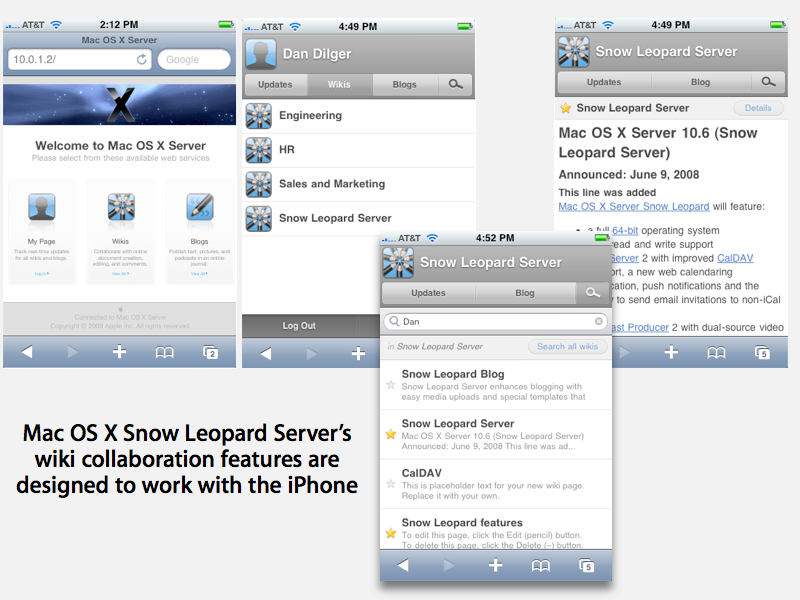

Mac OS X Server has the potential to leverage the iPhone's popularity among business customers because it offers companies with iPhones a variety of complementary services. Among these are wiki collaboration services that are specifically designed to work great out of the box on the iPhone (below) and a new Mobile Access service that allows iPhone users to securely obtain their email, contacts, and calendar and to access internal company websites using the same SSL protocol that banks use in their online operations.

Additionally, Apple supports Snow Leopard Server's CalDAV calendaring, LDAP corporate directory information, and standard Internet email on the iPhone, and supports push email and calendar updates from Server to the iPhone. The iPhone can't help but sell Snow Leopard Server, and the new Mac mini offering provides an easy, low cost way for companies to evaluate these features in supporting their iPhone users.

On page 3 of 3: Server Admin and Server Preferences.

One problem Apple faces in the server market pertains to scope and range. Is the company trying to be the vendor of a flexible, powerful foundation for building open source solutions which necessitates a certain degree of expertise to deploy and maintain, or does it want to offer a refined, point and click appliance that any Mac user can set up and operate?

Both options present plausible opportunities, but trying to deliver a single product that really fits both scenarios without hemming in power users or bowling over novices is certainly a tall order. And yet that's exactly what the company is trying to do. Rather than hit both targets with one shot however, Mac OS X Server presents two primary faces: Server Admin and Server Preferences.

Server Admin

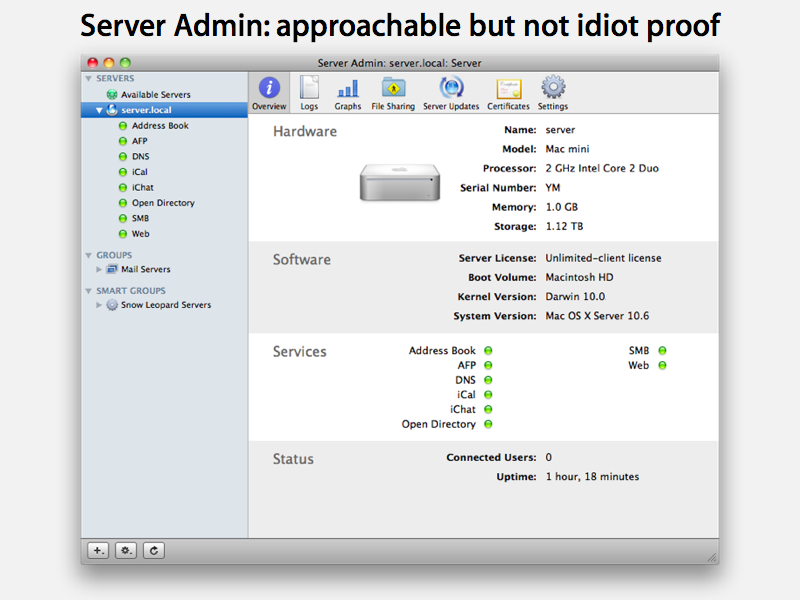

The first, and oldest, is Server Admin. From this single app, administrators can configure, monitor and manage every major service running on the system, from web, print and file sharing to email and calendars to directory services to video production workflows in Podcast Producer and everything in between.

Server Admin isn't really difficult for new users to figure out, but it presents a lot of complex options that entry level users could find overwhelming. It also exposes plenty of potential to set things up wrong or create configurations that don't make sense or result in problems that would be difficult and expensive to troubleshoot.

For the bleeding edge of power users, Server Admin might only address the majority of what they want to accomplish; users who want to install additional server packages are on their own, and must operate these with the same command line or web-based tools that experienced admins on any other *nix-based server system would use. These users have to proceed with some understanding of how Server Admin works in order to prevent conflict between it and their own custom system configurations.

Server Admin's sweet spot also happens to be Mac OS X Server's primary market: education users and small and medium sized businesses that serve Macs. However, this is not really Apple's mainstream user base. Server Admin presents nowhere near the straightforward usability of iLife and iTunes. In order to set things up using Server Admin, users will need a good grounding in moderately advanced server and networking concepts.

Server Preferences

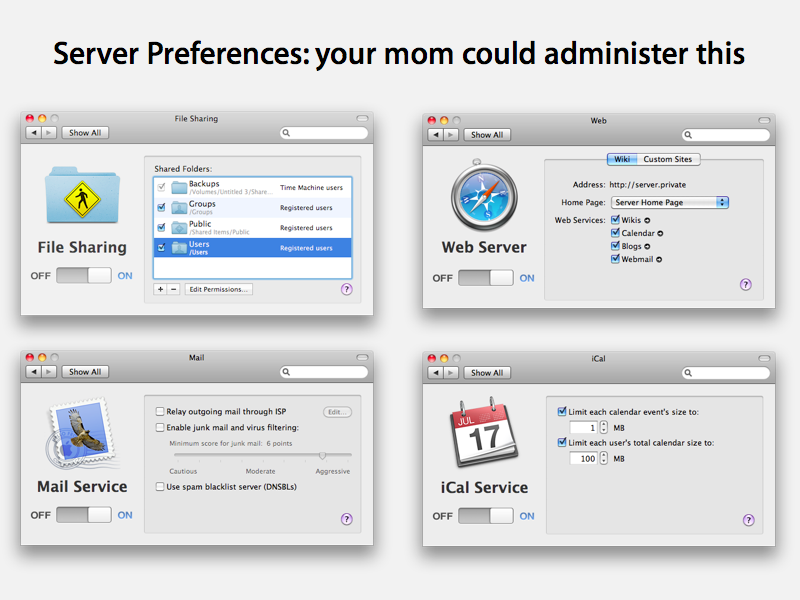

Starting with Leopard Server, Apple introduced a new, highly simplified server tool called Server Preferences. It's pattered after System Preferences on the Mac OS X desktop. It doesn't intend to support every service available, nor does to present more than a few basic options for each component.

During initial setup, users who opt for anything other than the advanced configuration are presented with the extremely basic Server Preferences. In very Mac-like fashion, everything is setup to "just work," although this occurs because all of the dangerous choices are simply unavailable.

Using Server Preferences is literally a matter of clicking large buttons, very similar to turning on Time Machine on desktop Macs. Turn a service on, and it's working, configured the way Apple thinks is best. If you want to customize things, you're probably out of luck because Apple has determined that anything you might adjust probably has repercussions you wouldn't anticipate and which would result in a complex and expensive troubleshooting problems that Apple Store Geniuses will only be able to answer with apologetically blank stares.

For users who just want a file server, email and instant messaging, shared calendars and contacts, an Intranet website with rich blogging and wiki features, along with Time Machine client backups and a VPN and basic firewall, Server Preferences does almost everything for you and works without really needing to crack a manual, the way most Mac users would expect of an Apple product.

Open Directory: you may not know you need it yet

Apple appears to be banking on Server Preferences to serve as the primary interface for Mac mini server users. Behind its toy-like simplicity, it actually provides lots of very powerful features that many home and small business users don't yet know they need, starting with Open Directory. Apple has integrated a variety of very complex and security-sensitive services, including LDAP, Kerberos and a SASL Password Server, and churned out a deceptively simple directory services product that just works, particularly for small installations where additional integration with other corporate directories isn't needed.

What Open Directory does is manage user accounts and passwords on a network level. Rather than dealing with individual user accounts set up on each Mac in your home or business, Open Directory allows you to create one listing of users that every Mac on the network subsequently consults.

This all sounds very boring, but it unlocks all of the interesting features of Mac OS X Server. It allows you to log into any machine on your network using the same password, and then seamlessly access file servers and services without having to present credentials each time. It also allows you to sync all your files between, say, a desktop and workstation via the server, and to share calendars among users, and to publish internal and public blogs and wikis. And once its set up, you should be able to pretty much forget about it.

The end of innocence

Once users get wind of what other things Snow Leopard Server can do, there's zero work involved in upgrading to an advanced configuration using Server Admin; you just open up Server Admin and begin turning on additional services.

Once this happens however, the childlike innocence of Server Preferences vanishes and you must take on the role of a server administrator, which most definitely will require consulting a reference, and perhaps even paying a consultant.

This makes Apple's choice to bundle its unrestricted, full version of Mac OS X Server on the Mac mini interesting. Users who know they don't want to bite off a complex bunch of trouble will be able to set the product up and use it under the simple Server Preferences. But curious or advanced users will have full control to take on as much complexity as they can manage.

Opportunities in small servers

As noted earlier, Microsoft sells a stripped down appliance version of its server software as Windows Home Server; this does little more than support web and file sharing and some PC backup utilities. There's no collaboration or messaging tools, no directory services domain, and no smartphone integration or anything else. It hasn't exactly taken off like wildfire.

Apple doesn't have a lucrative server software business to protect, so it can throw the whole Snow Leopard Server hog at users and let them set up anything they want, constrained only by the limitations of the Mac mini hardware. There's no missing features, no usage limitations, no client access licensing, and no essential server software that has to be purchased separately.

This is Apple's boldest step yet to expand the visibility of Mac OS X Server into untouched greenfields of opportunity in the emerging small server market. It's also one where there isn't much other competition. This will make it interesting to see how much attention Apple can draw for its new Mac mini server.

AppleInsider will be looking at how well Snow Leopard Server works on the low end, light duty Mac mini in future reports that examine Apple's new value proposition for home and small business users.

Daniel Eran Dilger is the author of "Snow Leopard Server (Developer Reference)," a new book from Wiley available now for pre-order.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Chip Loder

Chip Loder

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Michael Stroup

Michael Stroup

William Gallagher and Mike Wuerthele

William Gallagher and Mike Wuerthele