Almost three years after Google released its WebM video encoding technology as a "free" and open alternative to the existing H.264 backed by Apple and others, it has admitted its position was wrong and that it would pay to license the patents WebM infringes.

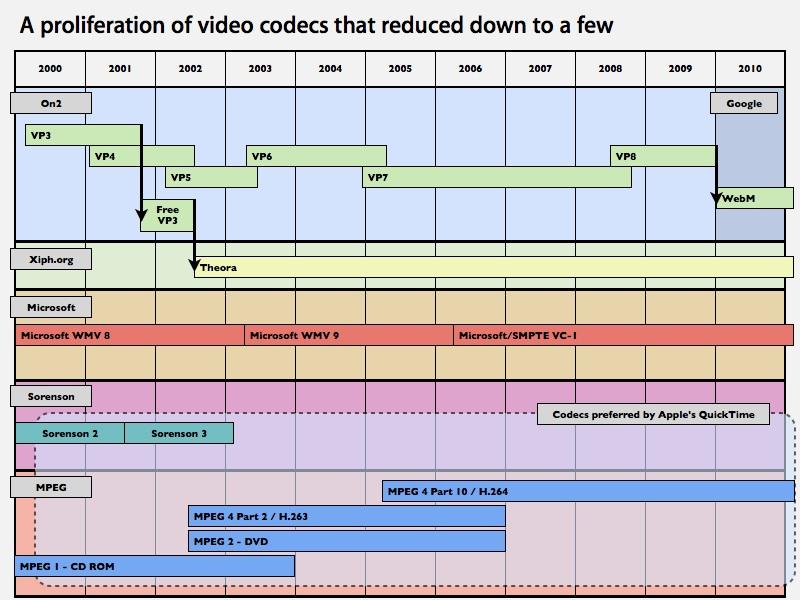

Google released WebM in 2010 after acquiring proprietary video compression tools vendor On2; it subsequently released that company's VP8 technology as a "licensing free" competitor to the International Standard Organization's established MPEG H.264 technology.

The announcement delighted some members of the open source community, particularly Opera and Mozilla, neither of which wanted to pay licensing fees for their use (or their users' use) of H.264. Both had previously supported Ogg Theora, an older and even less capable codec.

Google hoped to leverage its own strong position in web video, including its YouTube video sharing service and its popular Chrome web browser, to force adoption of WebM across the web. However, WebM had serious flaws, the largest of which is that it infringed upon H.264 patents itself.

After years of legal maneuvering, Google has now agreed to license the H.264 patents that WebM infringes.

"This is a significant milestone in Google’s efforts to establish VP8 as a widely-deployed web video format,†said Allen Lo, Google’s deputy general counsel for patents in a press release. “We appreciate MPEG LA’s cooperation in making this happen.â€

The latest Google IO announcement to collapse in failure

However, WebM faces serious other problems apart from its patent infringement. The legal quandary Google erected by failing to properly license MPEG's technology from the start means that it hasn't seen any significant traction from third parties, preventing any of these issues (including a lack of hardware decoder support) from actually being addressed over the past three years.

Just after Google launched WebM to great enthusiasm, AppleInsider reported that the new codec was being criticized by video developers, with one of whom, Jason Garrett-Glaser, "noting that it decodes video slowly, is buggy, and copies H.264 closely enough to all but guarantee patent issues."

This report received scorn by many who wished Google's plan would work out. But when Apple's Steve Jobs was asked about Google's WebM, he forwarded the person a copy of the Garrett-Glaser critique detailing WebM's problems in a clear endorsement of the logic explaining why no commercial vendor, particularly Apple, would adopt a less capable, flawed, and patent encumbered technology that only exists to unfairly compete against legitimate software and to give Google virtually unilateral power over the standards setting process.

Google's efforts to propagate WebM were similar to Microsoft's parallel efforts to push its own VC-1 codec (used in Windows Media Player and the ill fated HD-DVD) at the expense of H.264, which had the support of the rest of the industry and was developed in a partnership between vendors, rather than foist upon the web as something everyone else would have to accept. Like WebM, VC-1 was also found to infringe upon MPEG patents, derailing Microsoft's plans and resulting in its increased support for H.264 going forward.

Even ignoring patent issues, Google has faced poor adoption of a wide range of technologies it has promoted at its annual Google IO conference, starting with Google Wave in 2009; Android 3.0 Honeycomb tablets, Google Buzz and Google TV in 2010; ChromeOS, ChromeBooks and the Chrome Web Store in 2011 and Google+ and Nexus Q in 2012.

Google's second Flash

Despite these parallel failures, Google has worked hard to push WebM, defining it as the exclusive, required codec of Google's emerging WebRTC specification for web-based voice and video chat. The company also tried to make WebM the exclusive video plugin for Chrome.

However, the chips used by most smartphones and other mobile devices don't support WebM, making it much less efficient to present on any mobile device, as the devices must do all the decoding work in software. WebM also doesn't work on iOS devices at all, requiring anyone who wants to use it (and not exclude the vast majority of mobile video users worldwide) to also encode their videos in H.264, too, the same sort of "solution" proposed by proponents of preserving Adobe Flash on the web.

Mozilla and Opera initially also tried to prevent the use of H.264, but have since capitulated to support H.264 as a standard, leaving Google's WebM in virtually the same position it had as a new 1.0 product three years ago, but without any excitement surrounding it. This essentially makes WebM the equivalent of Flash in 2010: resolved of legal challenges but saddled with technical and performance issues, and incompatible with any devices running iOS.

Google to keep working on competitor to H.265

Going forward, Google plans to keep working on a new version of WebM called VP9, while the rest of the industry prepares to leap to MPEG's next generation H.265. Both new codecs promise to deliver similar video quality at around half the data rate (but requiring as much as three times the data processing capability), according to a report by Tsahi Levent-Levi.

That report also cited data presented by Google that said the the company's upcoming VP9 "is ~7% behind HEVC/H.265 in terms of quality/bitrate when they tested VP9 in Q4 of 2011 (They started developing VP9 in Q3 2011). Their goal is to become even better than HEVC."

While Google continues its efforts to splinter development on video technology going forward, mobile chip developers (such as Qualcomm, above) have a vested interest in incorporating new codec technology that will enable more efficient video at smaller file sizes, something that mobile carriers also want to see.

While Google was previously able to offer WebM as a "licensing free" alternative to H.264, its new licensing agreement means that WebM and its future versions can only offer a cheaper alternative if Google chooses to subsidize the technology. Apple, Microsoft, Cisco, network operators and chip producers will continue to pay the relatively low "Fair, Reasonable and NonDiscriminatory" fees collected by patent owners behind the MPEG H.264/265 pool in order to keep the pace of video technology moving.

Apple may add support for H.265 as soon as the next generation of its A7 chips, as it has aggressively adopted new standards (such as 802.11n wireless networking), often even before they have reached final status as official specifications.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

-m.jpg)

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

-m.jpg)

70 Comments

How much will they be charged in back licenses and penalties? This should be used as justification to re-visit every lawsuit Google won and lost to verify they told the truth instead of lying like they did about H.264. Everyone knows Google stole everything about all their software and this begins the proof. Let's see what the market does after this news--probably goes up because the market sides with the cheaters.

So that's a waste of $133 million dollars or are we living in a time when a company can blatantly steal from another *cough* Samsung *cough* yet profit handsomely despite clear and rampant violations?

[quote name="SolipsismX" url="/t/156365/google-admits-its-vp8-webm-codec-infringes-mpeg-h-264-patents#post_2290016"]So that's a waste of $133 million dollars or are we living in a time when a company can blatantly steal from another *cough* Samsung *cough* yet profit handsomely despite clear and rampant violations?[/quote] If you can't beat them, copy them.

Why admit it now and not before? How about admitting that Google stole Java technologies for Oracle and iOS technologies from Apple?

Read the press release.

http://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20130307006192/en/Google-MPEG-LA-Announce-Agreement-Covering-VP8