Mozilla considers H.264 video support after Google's WebM fails to gain traction

Last updated

The move is necessitated by the overall lack of support for Google's WebM video codec, which Mozilla and Google hoped would replace H.264, the technology backed by Apple, Microsoft, Nokia and other commercial vendors.

Mozilla's war on H.264 has gone on for nearly three years, but now the company's leading developers have admitted, "we lost."

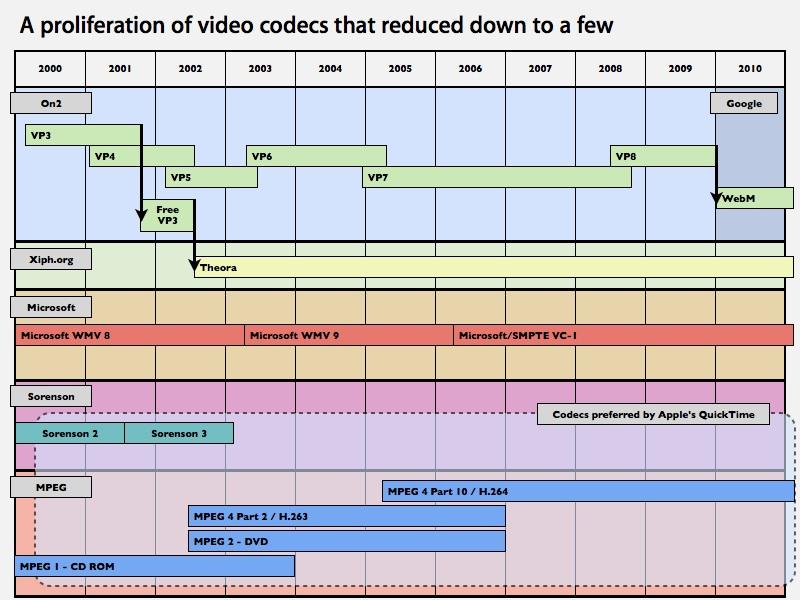

The Ogg Theora war on H.264

Beginning in mid-2009, Mozilla and browser developer Opera tried to dictate the use of the freeware "Ogg Theora" codec as the official way to present video on the web using the emerging HTML5 specification, in hopes that it would prevent the ISO's MPEG H.264 standard from becoming the standard for web video.

For years prior to the Ogg Theora debate, Apple had aggressively pushed H.264 in iTunes as the most technically sophisticated, efficient way to deliver video, essentially standing on the shoulders of the industry giants who had each contributed various components of the standard to become state of the art in video compression.

While H.264 is an open standard, it is not free. It is based upon a pool of video compression and related technology patents contributed by various companies in exchange for "Fair, Reasonable and Nondiscriminatory" licensing fees. Mozilla, Opera and other free and open source advocates opposed the use of any technology that might require licensing fees to produce or distribute web content.

Commercial hardware developers, led by Apple and Nokia, opposed any shift toward Ogg Theora in H.264, noting that H.264 was far ahead of the older Ogg Theora video technology in technical sophistication, and that hardware decoding was already well established in place to accelerate H.264, particularly in mobile devices.

Replacing H.264 with Ogg Theora to placate Mozilla and Opera's insistence upon cost-free video encoding for the web would have broken the ability of millions of smartphones, iPods, netbooks and other mobile devices to efficiently play back video. Additionally, Google noted at the time that Ogg Theora was not powerful enough to serve the billions of video streams it was delivering via its YouTube service.

The Ogg Theora war on H.264 ended when HTML5 working group members agreed that rather than defining Ogg Theora or H.264 or anything else as the "baseline" codec for video served via the HTML5 video tag, the decision should be left to the market and to the votes of web users and Internet broadcasters to decide.

This decision paralleled how HTML has always worked with every other type of media file; there is no baseline graphic or audio format, for example; instead, web publishers decide for themselves whether to use GIF, JPEG, or PNG graphics formats and whether to use MP3, AAC, or raw WAV audio files. Modern browsers support them all.

The WebM war on H.264

At the end of 2010, the war on H.264 was reignited, this time by Google. After having converted its massive library of YouTube videos to H.264 in a partnership with Apple to shift web videos from the constraints of Adobe Flash and make open video viewable on devices that lacked the ability to run Flash, Google decided to buy On2's VP8 (a newer generation of the VP3 codec Ogg Theora was based upon) and release it as a "free" codec named WebM.

Because WebM was technically capable of serving YouTube videos, Google now hoped to join Mozilla and Opera in turning back support for H.264 video on the web and replacing the H.264 codec with a free alternative it claimed to be unencumbered by patent claims.

This strategy shared some similarity to Apple's war on Adobe Flash using the free and open HTML5, which Apple successfully pursued over the five years following the release of the original iPhone.

However, WebM was "unencumbered" by patents only in the sense that Google didn't plan to charge royalties for its use itself. It was still based on technologies that the MPEG Licensing Authority claimed to own, making it no less "encumbered" than H.264. Microsoft had earlier learned the same lesson when its own Windows Media Video (aka VC-1) codec was found to be infringing a variety of technologies already patented by MPEG members who had pooled their expertise to create H.264.

Creating an illegitimate, infringing copy of H.264 is no more legally legitimate than simply implementing H.264 and failing to pay licensing fees. However, Google was emboldened by having done essentially the same thing to JavaME in order to create Android, and having suffered no consequences for it. So it began a campaign to derail the adoption of H.264 in HTML5 and aggressively push WebM as its substitute at the beginning of 2011.

A year later, Google's WebM hasn't gained any more traction than Google Wave, Google Buzz, Google TV or Android 3.0 Honeycomb tablets. In part, this is because H.264 is the only way to serve videos to Apple's iOS devices, a factor that also helped to rob Flash of critical mass among mobile devices.

However, Google also never removed H.264 support from its own Chrome browser as it had promised to do. And even among other browsers that had effectively made WebM the only default way to present HTML5 video (including Mozilla's Firefox and the Opera browser), there was still a fallback in place to use Adobe Flash.

That meant video content creators could reach all audiences using H.264, and simply route around the idealogical position of Mozilla, Opera and now Google by wrapping their videos with Flash. There was no exclusive audience that could only be reached by WebM, and therefore no real advantage to using it.

However, there is a big advantage to using H.264: support for efficient hardware acceleration exists for it on all modern mobile devices. Mozilla's new softening stance on the issue seeks to allow this underlying hardware support (or the operating system, such as Windows Phone 7 or Android) to perform the H.264 decoding on behalf of the browser.

The war on H.264 is over: "We lost," says Mozilla

Gal announced plans to add a feature that "adds hardware-accelerated audio/video decoding support to [Mozilla's] Gecko [browser engine] using system decoders already present on the system," including "hardware-accelerated decoders for good battery life (and performance)."

He noted, "We will support decoding any video/audio format that is supported by existing decoders present on the system, including H.264 and MP3. There is really no justification to stop our users from using system decoders already on the device, so we will not filter any formats."

The mechanism will apply both to Mozilla's own "Boot2Gecko (B2G)" mobile operating system as well as Android, although Gal stated that "on Android we might have to add a second video path using overlays which would only work with a small subset of CSS since extracting video frames isn't supported on all versions of Android (and all devices).

"I don't think this bug significantly changes our position on open video," he wrote. "We will continue to promote and support open codecs, but when and where existing codecs are already installed and licensed on devices we will make use of them in order to provide people with the best possible experience." Gal also noted plans to add similar technology to the desktop version of Firefox, allowing the host operating system or available hardware to render video or audio as needed.

Adding such an option to Firefox for Windows would mean Windows 7 users could render H.264 but the installed base of Windows XP could not, unless Mozilla actually bundled H.264 codecs with its browser. This additional complexity is pushing Mozilla to focus first on adding the ability to render H.264 to mobile devices, something that would help Firefox on Android, which lacks the ability to render H.264, the format most web videos now use.

Noting the necessity of supporting H.264, Mozilla's Open Source Evangelist Christopher Blizzard noted, "We've only seen [WebM] format adoption on YouTube. Basically everyone else uses H.264 & Flash. There are occasional exceptions, but it's not getting better with time."

Asa Dotzler, Mozilla's product director for the Firefox added, "We're talking with major video sites and they're saying 'no' to WebM. The costs of transcoding huge libraries just doesn't make sense to them.

"Firefox on Desktop is experiencing these same 'significant deficiencies' and the tide is not turning in any appreciable way. All that's happening while we wait is that Web developers are embracing other browsers and their primary targets.

"What I fear people aren't getting here is that Gecko is the _only_ mainstream browser that doesn't support h.264. We lost. It's not like we're at some tipping point and it's 3 of 4 browsers on the side of royalty free codecs with the forth about to agree. Things have tipped the other way and to not realize that and continue to hold out for a change that will not happen does little but cost us users and developer mindshare.

"It's time to bite that particular bullet and deliver h.264+AAC (and probably mp3) in Firefox — across all platforms and devices."

Android powerless to push WebM over H.264 in the way iOS pushed HTML5 over Flash

This is a turnaround of the situation Google intended to create in starving iOS devices of H.264 content by leveraging Adobe Flash, which in 2010 became exclusively available for Android (shortly before Adobe gave up on Flash for mobile devices in recognition that its War on Apple wasn't going to work out).

If Android could play both Flash videos and WebM, Google expected to be able to either force Apple to adopt Flash or WebM. Instead, Google is rethinking its position on H.264, bundling the legally grey ffmpeg H.264 decoder with Chrome, and bundling an Apache License 2.0 implementation of H.264 with Android.

Even Mozilla, representing the ideological left flank of its partners, is throwing its support behind H.264 out of necessity. And so, another war is over: H.264 first defeated Microsoft's VC-1 in HD-DVD, defeated proprietary codecs used by Flash, and has now defeated Google's attempts to replace it with its own WebM.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

Thomas Sibilly

Thomas Sibilly

AppleInsider Staff

AppleInsider Staff

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

65 Comments

My guess is In FireFox 33, at the end of the year... In case you didn't catch it, this is a facetious post aimed at the insane versioning of FireFox...

My guess is In FireFox 33, at the end of the year... In case you didn't catch it, this is a facetious post aimed at the insane versioning of FireFox...

Which, Ironically, was done as a response to Chrome.

Which, Ironically, was done as a response to Chrome.

You're right... Generally pay no attention to Chrome. but was shocked to see that they recently went to v18...

... Creating an illegitimate, infringing copy of H.264 is no more legally legitimate than simply implementing H.264 and failing to pay licensing fees. However, Google was emboldened by having done essentially the same thing to JavaME in order to create Android, and having suffered no consequences for it. ...

I love this part.

So totally 100% true (even though a lot of people will see that as simply authors bias considering Daniel is the author).

This is my sole reply to Mozilla for something that was obvious from day one.