Apple's five year effort to radically enhance iOS app advertising with its own ad sales has now been scuttled. That opens the door for an even more radical rethinking of how to monetize apps and Internet services, one that is clearly differentiated from the incessant adware associated with Android, Windows and the open web.

Over the past five years, Apple's inability to significantly challenge Google's mobile ad sales with iAd has pleased advertisers who bet against Apple's vision for advertising and instead threw their support behind Google and other ad networks with few qualms about the privacy of users.

Meanwhile, Apple has grown into a massively profitable mobile hardware company with a passionate user base, while Google has only made minor progress in wringing money out of mobile ads while earning virtually nothing from hardware sales.

Apple's revenue from iPhone and iPad exceeded $130 billion in 2014, compared to $11.8 billion in Google's mobile search revenue from that year. Three quarters of Google's mobile revenue— nearly $9 billion— came from iOS, according to Goldman Sachs analysis cited by the New York Times last summer. iOS generated over 40 times more revenues for Apple than Android contributed for Google

That indicates iOS generated over 40 times more revenues for Apple than Android contributed for Google, even before considering iTunes, App Store, Apple Pay and devices like Apple Watch and Apple TV.

Apple's exit from the mobile ad sales business may look like a win for Google, but it really signifies that Apple is ready to stop playing in ads where Google has a home field advantage, and instead begin to leverage its entrenched position in hardware in order to starve Google's core business into irrelevance by targeting the valuable foundation of Internet ads.

Corporate death by competitive starvation

Over the last five years, Apple has done really well in hardware. It is one of the only consistently profitable PC or smartphone makers. It has essentially crushed its hardware competitors by starving them of profits while reinvesting is own earnings into vertical integration. This has created a starvation cycle of making Apple's products better and more attractive, while erasing market potential for rivals.

Once-fierce PC competitors like HP have been neutered. Samsung has seen its mobile products collapse without recovery. Apple now claims a massive share of global profits earned in PCs, tablets and smartphones largely because there are no other companies left earning competitive profits.

It looks like iAd was intended to do the same thing to Google, but it failed to have a similar impact. Making superior products and dominating demand are one route to success, but it's not the only one.

Another way to overcome more powerful and entrenched rivals is to derail the demand for their products. Changing the rules of the game to emphasize the value of one's own strengths and devalue the core competency of one's competitors is nothing new in the tech industry.

Platform value wars: Microsoft "opens" PC hardware

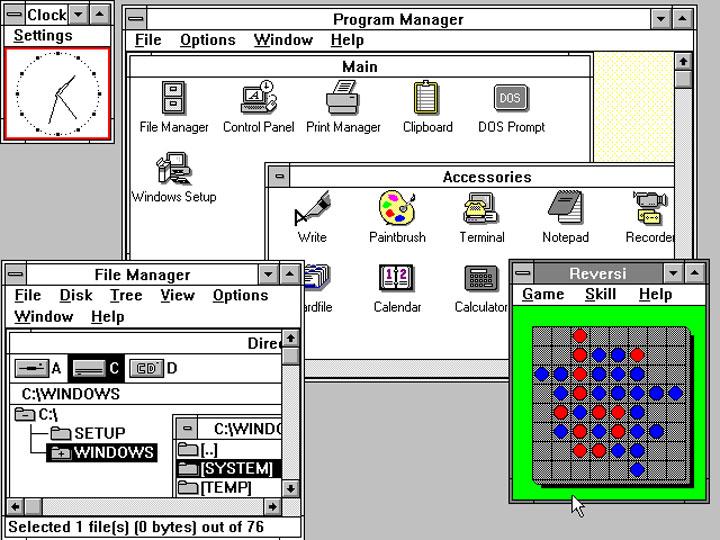

For example, in the early 1990s Microsoft cut Apple's Macintosh out of commercial relevance by shifting the value of its Mac Office apps onto a Mac-like platform it branded Windows. With Windows, users no longer need to pay a premium for Apple's hardware, leaving hardware "open" to various Windows hardware licensees.

Microsoft concentrated the perception of value on its own PC software, and left the hardware business (that it didn't really care about or understand or see any value in) to hardware partners. PC makers competed for scraps while Microsoft skimmed the cream off the top of the industry for two decades.

Apple of the 1990s was slow to realize that the overall market might find greater value in running familiar desktop apps on generic PCs. In particular, Apple underestimated the very basic Windows product Microsoft was offering at a relatively low licensing fee. Apple had expected PC users to gravitate towards more powerful software (like Unix or IBM's OS/2, both of which Apple was collaborating with), and ended up getting blindsided.

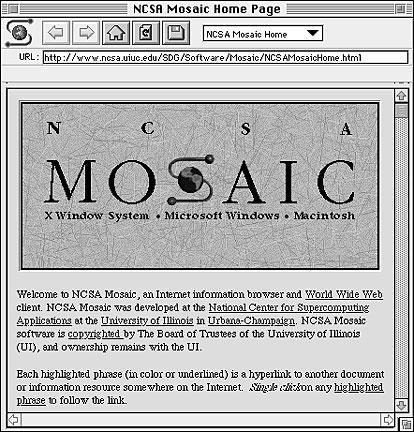

Platform value wars: Web seeks to "open" software

That same decade, Netscape and Sun worked to develop the web as a "open" platform, hoping to shift value away from Microsoft's software platform. Microsoft realized belatedly— but soon enough to change course— that if web apps opened up software the way it had opened up hardware, it would be left in the same beleaguered position as Apple.

Microsoft responded by working to make Windows more valuable and necessary (tying emerging web features to Windows APIs). As a result, Microsoft largely retained control of the PC over the next decade.

In the 2000s, Apple similarly regained some PC hardware share by making Mac hardware more valuable and necessary (tying apps such as Final Cut Pro and Garage Band to its platform). On a much smaller scale, Apple won back market share for Macs.

At the same time, Google began working to do what Netscape and Sun had failed to do earlier: shift web apps away from Windows by breaking the tie between Microsoft's platform and "valuable and necessary" web services. This "openness" benefitted end users, and opened the door for Apple as well, because open web apps could work as well on Macs as they did on Windows.

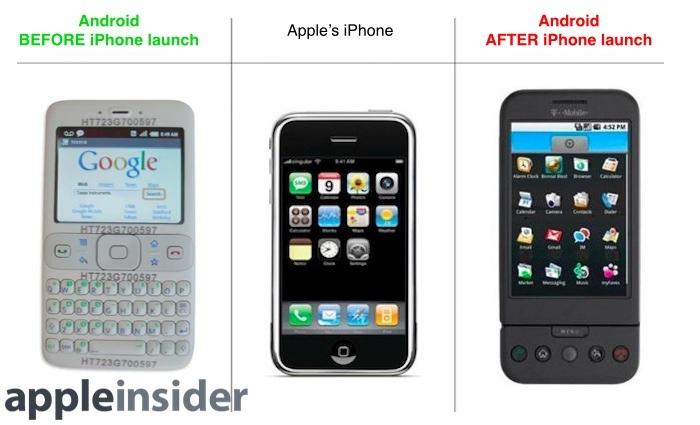

Platform value wars: Android seeks to "open" mobile hardware

Apple's subsequent introduction of iOS as new hardware-based platform again created a valuable app ecosystem tied to Apple's hardware, but "open" to third party development. In response, Google sought to replay Microsoft's strategy: it reintroduced Android as a rival to steal away iOS' app value and plant it on a platform that Google controlled, one that would again be "open" to alternative hardware makers.

Unlike Microsoft's Windows, however, Google's Android didn't directly deliver any significant licensing revenue to Google. Android has been subsidized by Google's core business of search-related PC advertising, which ties monetization of most everything on the web to Google's ads.

While pundits like to marvel about Google's supposed "80 percent share" of mobile hardware sales, the reality is that virtually all of Google's profits come from advertising. That means that if Apple wanted to drain Google of its income, it wouldn't need to take away a significant chunk of Android's hardware sales as it did with Samsung. It would take away Google's advertising revenue. That would be obviously disastrous for Google, because it has virtually no other sources of income.

Platform value wars: Apple seeks to open content

Apple's iAd appeared to be a way for Apple to muscle away Google's ad platform and tie the value of ads to iOS, much the same way that Microsoft had earlier tied the value of the web to Windows. However, ads aren't a value to end users; they're a tax.

Over the past several years, it's become clear that Apple is now seeing that there's more value in not having ads than there is in owning advertising on iOS. This indicates that going forward, Apple can court more satisfied customers— the people who pay a premium for its high-end hardware— by offering more privacy than from offering more private ads.

Faced with direct competition from Android "opening" up mobile hardware, what Apple has needed was a way to offensively "open" up monetization of content, software and services so that it's not tied to Google's ads. In parallel with the development of iAd, Apple has been on an incessant march to develop premium, desirable hardware that contributes enough profit to fund the development of competitive software and services that deprive Google of ad revenue.

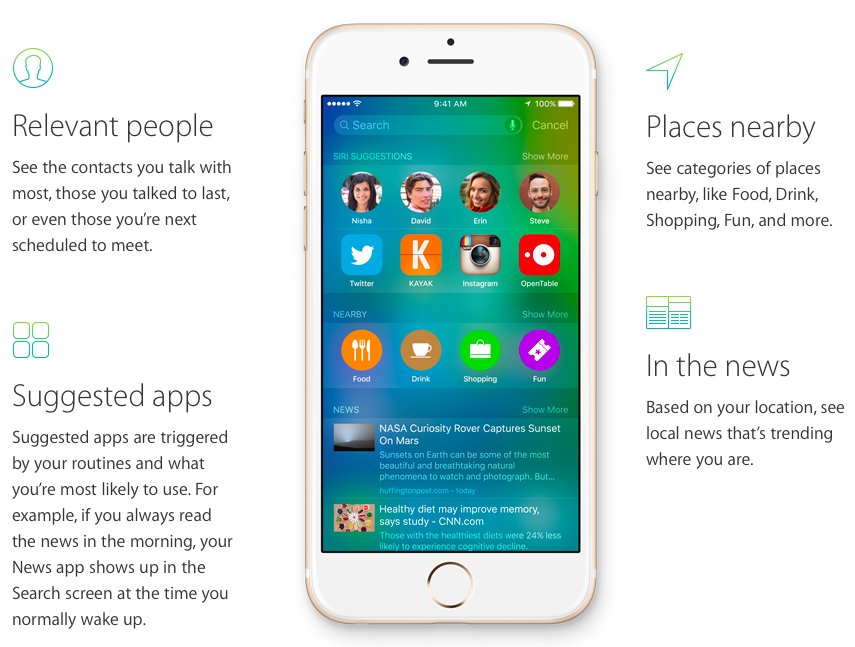

In Search, Google's core competency, Apple has invested in Siri and Maps and partnered with Yahoo, Microsoft, Wolfram, DuckDuckGo and other data providers to answer questions and find information independent of Google. Apple's services aren't yet on par with Google in every respect, but each time users check the weather, get sports scores or do research without involving Google, Apple reduces traffic from the most valuable demographic of users to its primary rival.

In the App Store, Apple has shifted users' routine computing and entertainment tasks from web pages to individual native apps. Web apps once promised to rival desktop software, allowing end users to do anything online and "in the cloud." However, on mobile devices, Apple has shifted work from the browser to efficient, native apps that are easy to use and cheap to buy.

The App Store has created a curated market for apps that gives Apple a share in the success of developers, and has introduced In App Purchases as a route to recurring revenue, a sort of on-demand subscription model. Third parties (including Microsoft and Adobe) have also brought a subscription model to software apps, and content providers (like Netflix and Hulu) have done the same for media.

Google also has an Android app store. Who knows why? It should be pushing web (or native thin client) apps that focus the user on the web, where it already has ads. Instead, it blindly copied Apple before realizing that it knows little about native platforms or how to manage them.

It then started over with Chrome OS, a browser running on Linux. This made a lot more sense for a web-oriented company. Unfortunately for Google, Chrome hasn't been able to win users back from an app-centric model. Google is now working out how to move forward, but its strategy is rather limited by the broad distribution of Android and its iOS-like app focus.

In a world of apps, users go directly to an app to begin looking for things. In the desktop world, users often start with a web page opened to Google, and begin searches that present results right next to sponsored ads. This "paid search placement" advertising has been very effective for Google, because it puts ads right in the context of the users' needs. Ad banners in an app are not effective at all; they are a distraction. They pay virtually nothing because do little of value for advertisers and users hate them.

A world centered on apps is terrible for Google, but it's great for Apple. The best apps are on iOS, and iOS is tied to Apple hardware. Microsoft is working to undermine that by making iOS apps easier to port to Windows mobile devices, but the tiny installed base of Windows outside of conventional PCs makes that a real uphill challenge.

Next to apps, Apple Music has introduced a subscription model for unlimited, on demand music and videos. Part of the Apple Music package is Beats 1 radio, a commercial free Internet radio broadcast that Apple essentially subsidizes to draw attention to Apple Music.

Apple also sponsors events like the Apple Music Festival and the recent Taylor Swift tour video, paid to produce new music videos and runs its Connect service, an ad-free social media feed for artists. This direction of ad-free content suggests the potential for more new and original material paid for by subscriptions or subsidized by Apple itself.

Apple's previous foray with iTunes Radio attempted to use advertising to pay for basic music streams. However, that model is too weak, because ads don't really contribute enough to pay for content. By switching music to a subscription model, Apple can gain enough revenue to subsidize the music industry without ads. Google should be really worried about that.

Google hopes to monetize its vast library of YouTube videos with ads, but these ads are not nearly as effective or valuable as paid search placement. Google wants to turn YouTube into a market more like iTunes, and now has its own Apple Music-style subscription plan for YouTube videos. However, the main attraction to YouTube is that it's free. Tacking a minute long commercial in front of a minute or two of content does not seem like a sustainable way to monetize content. It also remains to be seen whether subscribers will flock to play to watch YouTube content.

Apple TV offers another example of the App Store and Apple Music at work: by selling content rather than funding it via advertising, Apple is creating a source for higher value, premium entertainment. The company's ongoing intent to build an Apple Music-like subscription program for TV will expand upon this premise. Comparing the value of ad-supported broadcast TV with premium services like HBO or Netflix makes it clear how much better the latter is at creating valuable content.

Apple News is another example of Apple trying to distill value for users. At first glance, it looks like an ad-supported capitulation to the stinging failure of Newsstand, which sought to sell app-based periodical subscriptions. But without iAd revenue, News is just a free service Apple is setting up for news sites, with their participation based on their own advertising. That makes News essentially another Maps: an app that deprives Google of opportunity while generating no revenue of its own.

Going forward, Apple has a lot of ways to muscle into Google's role as the monetizer of content. While today's Apple News looks more like iTunes Radio, a future subscription service more akin to Apple Music would give Apple's users a high quality source for journalism, news and commentary. An equivalent service for TV content could also generate subscription revenue targeting cord cutters.

The stronger iOS' content and information services get, the harder it will be for Google to remain stuck relying upon desktop PC search paid placement to subsidize its expensive development of Android and other moonshots. Display advertising isn't going to make up for the evaporation of the the PC browser pointed at Google search as the world moves toward apps.

Diminishing value of display ads

Advertising is unlikely to ever go away entirely. However, there is a clear trend toward minimizing display advertising as demographics gentrify. Poor neighborhoods are emblazoned with billboards and ads. Rich neighborhoods are not. Advertising is increasingly restricted in neighborhoods as land values climb. There's a general revolt against invasive advertising the higher you climb in sophistication and wealth.

That puts Apple on the right side of a trend compared to advertisers like Google and Facebook. So far, Apple has been winning: it makes far more money from mobile device hardware than Google or Facebook will make from mobile advertising.

Apple is often presented as being on the losing side in conflict with Google and its powerful advertisers and partners. However, Apple has a powerful partner of its own: the end users who decide what they want to buy. Consider what iAd actually intended to do, and why advertisers rejected it, and what Apple is likely to do next.

Why Advertisers hated iAd

In 2010, Steve Jobs introduced iAd as an eyebrow-raising tentpole feature of iOS 4. In the audience, it seemed hard to fathom how ads could be a feature.

At the time, Jobs noted that app developers "need to find a way to start making their money. A lot of developers turn to advertising, and we think these current advertisements really suck."

He pointed out that when users clicked on existing iPhone mobile ads, they were typically yanked out of the application they were in and taken to a browser window's web ad. Because they had been dropped into another app, finding their way back to the task at hand was more confusing and annoying compared to the desktop web experience, where users could at least close annoying popup ad windows to get back to work.

Additionally, at the time much of the web's advertising infrastructure was built around Adobe Flash, making it more difficult for advertisers to reach iOS. At the time, there was intense pressure upon Apple to find a way to shoehorn the flawed, resource intensive Flash into iOS.

Conversely, Google jumped to bolt Flash onto Android, enabling desktop PC-like ads for its rival platform. The ad-supported media almost unanimously agreed that Flash and its ads would be a strong differentiator for Android that would help give it the edge over iOS on tablets. They were very wrong. Flash didn't ever work very well on Android, and it introduced lots of problems.Advertisers hated that Apple's iAd was preventing them from gaining full access to user demographics and behaviors

Meanwhile, iAd offered an alternative to Flash, as it was built entirely using HTML5 web standards. The goal of iAd was to create a platform-integrated, interactive web session that could be entered within the context of an app and dismissed at any time to return to the app. To kick things off, Apple repurposed Quattro, an existing ad network, into Apple's own in-house ad studio.

Advertisers hated working with iAd, but not because it failed to improve the ad experience, or because it was technically inferior, or because it failed to engage audiences. Advertisers hated that Apple's iAd was preventing them from gaining full access to user demographics and behaviors— the way Google, Adobe and the other mobile ad networks were working to facilitate.

Apple's increasingly vocal stance on the side of consumer privacy— which has only grown more strident over time— was standing in the way of advertising nirvana: the non-stop audience surveillance program that could be distilled into the sort of pure profit brand manipulation depicted in futurist movies such as Minority Report, where billboards literally leap into your face and talk to you by name, coaxing you to buy with the savvy of a salesman pretending to be your best friend.

Enhanced Ads on the web

Rather than catering to advertisers, Apple increasingly locked down the iOS app platform and its developer guidelines to block third party developers and ad networks from installing the kinds of cookies and trackers they had grown accustom to using on the web.

While the web had started out in the early 1990s as a model for linking pages of information between peers, it quickly morphed into a client-server model where user clients automatically and invisibly volunteered tons of identifying information to centralized web servers every time they requested any information.

Rather than having a only a basic picture of their audiences as newspapers, radio and TV broadcasters previously had, web servers could report exactly how many views a given page received, along with the geolocation of each user and a profile of the hardware each audience member used to access the server. Web browsers also report how the user happened upon the web server, whether "organically," or from a search engine referral.

This treasure trove of audience data continued to grow richer and richer. Web servers began planting "cookies" on web client machines, enabling them to track users by cross-referencing their browsing history across different sites.

Because this increasingly sophisticated web tracking surveillance and record keeping remained largely confined to tech audiences, the public rarely even knew they were being watched and monitored and analyzed in a way to predict how to best deliver effective advertising to them.

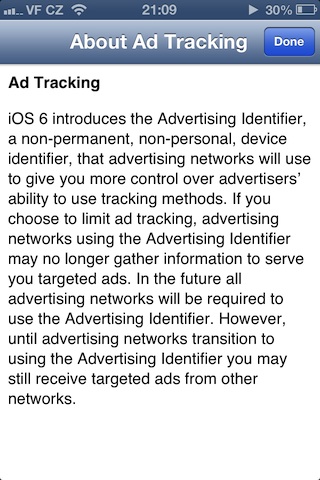

Once web advertisers started seeing the potential of mobile apps, they worked to introduce the same techniques. Google embraced this in Android, but Apple increasingly erected barriers, blocked access to hardware without clear user permission, and eventually limiting advertisers from even using a universal, unique identifier at all in iOS 6.

Advertisers got angry, and many threw their support behind Android and its "open" support of proprietary Flash and virtually unrestricted access to user tracking and deep surveillance. After all, Google was an advertiser first and a platform developer second. Android was designed first to serve advertisements, not making things difficult for advertisers.

Standing in advertisers' way was the pesky fact that the most valuable demographics they sought to target— better educated, affluent, trendy young parents, their kids and wealthy seniors— were consistently preferring to use iOS devices. Now that Apple has given up on iAd, the most valuable demographic of mobile users are likely to gain nothing but further privacy protections from Apple, because that differentiation from Android is far more valuable to Apple than the goodwill of advertisers

The demographic that Google's open Android attracted were poorer budget seekers who didn't want to pay a premium for hardware, for apps, for media, or really anything. Broadly, they were more willing to pirate apps and online content. That's not who most advertisers want to target with their brand messages.

Advertisers want to reach iOS users, but largely didn't want to support iAd, given that more privacy-encroaching alternatives existed. But now that Apple has given up on iAd, the most valuable demographic of mobile users are likely to gain nothing but further privacy protections from Apple, because that differentiation from Android is far more valuable to Apple— and its hardware centric business— than the goodwill of advertisers.

Last summer, Apple introduced WebKit Content Blockers as a secure new App Extension to enable developers to create tools that filter out any web content, including display ads and user tracking.

In giving up iAd's effort to copy Google's advertising business and instead working to increasingly make analytics-based advertising commercially irrelevant, Apple could do to Google what Microsoft did to Apple 20 years ago: starve it into beleaguerment.

Good luck with the robots and dirigible internet.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

-m.jpg)

Andrew O'Hara

Andrew O'Hara

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Andrew Orr

Andrew Orr

Sponsored Content

Sponsored Content

85 Comments

Revenue is a misleading measure. Cost of sales for hardware is much more than for search.

Only a couple of paragraphs on the interesting question of why iAds failed, buried at the bottom of the article.

The problem with iAds was the same problem that Apple Maps now suffers - a lack of ubiquity. If I'm an advertiser, I want my campaign to work across the web and mobile. iAds made that less cost-effective.

Robin

: Holy smokes Batman....

Batman: What is it Robin?

Robin: Did you see that?

Batman: No Robin, I didn't...

Robin: It was one of the most well written articles I have read in a while, regarding Google vs Apple.

Batman: How well was it Robin?

Robin: So well I took time to register as a user on Appleinsider so I could tell the author great job, and to keep up the good work, but his name is nowhere to be found.

Apple could poach the best content from Youtube and offer it on Apple TV as part of a subscription which included films and other content. This could royally screw Google over further.