Inside App Extensions: WebKit Content Blockers extend user privacy in iOS 9, OS X Safari 9

Last updated

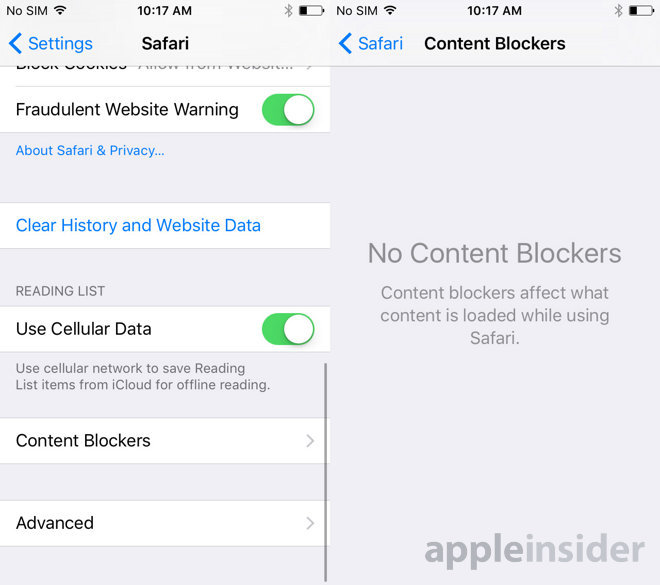

Last year, Apple introduced App Extensions to enable third party developers to add system-wide features using a secure new architecture. This year, iOS 9 and OS X El Capitan introduce a new Content Blockers category of App Extensions, specifically targeting Safari.

Apple previously introduced App Extensions at WWDC 2014, grouped into categories targeting specific functions. These include system-wide Share Extensions, Photo Editing Extensions (extending the features of the Photos app), Today Extensions (supporting widgets) and Custom Keyboards specific to iOS. Content Blockers are a new class of App Extensions specially targeting Safari.

Because the most obvious role for Content Blockers is to allow users to remove advertising from webpages, this new functionality has generated controversy and raised alarms among web publishers concerned about losing the already limited revenue they earn from banner ads, as well as the potential loss of cookies they might use to help enforce paywalls around their content.

Many of the same journalists who have been cheering for "free" music and unpaid distribution of bootleg movies— while chiding music labels and movie studios to "change their business models to align with popular demand for free content"— are now finding themselves facing a similar dilemma: how to get paid for creating content their audiences can easily access without paying anything for it.

Before considering the issue of web content without forced advertising and behavior tracking, first take a look at how Content Blocker App Extensions work and what they are designed to accomplish.

What are Content Blocker App Extensions?

New Content Blocker App Extensions for Safari on iOS 9 (and Safari 9 on OS X El Capitan) target subsets of web content or resources, preventing them from being shown or even being loaded in the first place. This can include display ads, images, navigation elements, popups, scripts, fonts, style sheets, media files, cookies, or essentially anything on a web page.

Using Safari's Web Inspector, an App Extension developer can select any portion of a web page, from a specific image or advertisement to an HTML div tag encapsulating a block of user comments, and then create a rule list that tells Safari to not show— or even never load— that resource when visiting the site.

Blocking content has already been available as a feature in OS X since Safari 5 (via Safari Extensions), but is entirely new to iOS 9, as iOS has never previously been able to load any type of extensions (including legacy plugins such as Adobe Flash Player or Microsoft Silverlight).

Outside of Apple's platforms, web browser extension architectures already support ad blockers on Google Chrome, Mozilla Firefox and even Google's mobile Android browsers. Google is, of course, not particularly supportive of blocking ads, because it makes the majority of its revenues from advertising.

Instead, Google and other advertisers have partnered with "ad blockers" to prevent competitors' ads from being shown, while whitelisting their own advertising, according to a report by the Financial Times.

A major architectural change for Safari 9

Apple's implementation of Content Blockers as App Extensions is a major architectural change for Safari 9, both on iOS devices and the Mac.

Most web browsers (apart from iOS) have long supported plugins, which are binary code that the browser loads to handle specific types of media files, such as Flash, PDF or SVG. These are notorious for hogging memory and introducing stability problems and security vulnerabilities (the main reason why Apple did not support plugins in iOS at all, and why it sandboxes them in Safari to limit the damage they can cause when they crash or are exploited).

In Safari 5, Apple introduced Safari Extensions (built using JavaScript, HTML and CSS) to enable third party developers to add new browser features, ranging reformatting the content of loaded pages to translating text into another language, to removing images or blocking ads. However, because they manipulate web pages as they are loaded, they can also consume lots of memory and processor resources.

App Extensions differ from Safari Extensions in that they are built in native code (distributed with a companion app). This makes them both more powerful and more efficient than Safari Extensions, largely because the new architecture allows apps to instruct Safari to block content before it is ever loaded, rather than Safari involving a JavaScript Safari Extension during its loading and rendering process.

Apple created the new App Extension model for Content Blocking for iOS 9, but is also bringing it to OS X El Capitan, even though there is already a Safari Extensions mechanism to do the same thing. That's because the App Extension approach is both faster and more memory efficient.

Designed with privacy in mind

A side benefit to Content Blockers being implemented as an App Extension is that they perform their intended function without knowing (or recording) what content the user is actually browsing, eliminating privacy concerns.

Safari App Extension Content Blockers can't see URLs of the pages or other resources the user has requested, because they only define rules of what Safari should block. WebKit also does not record which blocking rules have been executed on specific URLs."There is a whole universe of features that can take advantage of the content blocker API, around privacy or better user experience." - Benjamin Poulain

Regarding Content Blockers, WebKit developer Benjamin Poulain notes, "we have been building these features with a focus on providing better control over privacy. We wanted to enable better privacy filters, and that is what has been driving the feature set that exists today. There is a whole universe of features that can take advantage of the content blocker API, around privacy or better user experience. We would love to hear your feedback about what works well, what needs improvement, and what is missing."

In addition to blocking the display of advertising (or other distracting screen elements) the way Safari Reader does, Content Blockers can actually not only prevent visible ads from loading, but also block invisible JavaScripts or other elements that web publishers or advertising networks use to track users and identify them across web properties.

Content Blocker App Extensions define "triggers" that identify specific types of resources on a given domain, and then tell Safari not to load them as part of the page. A specific rule can also differentiate between first party resources (hosted by the website the user is intending to visit) and third party resources (injected into the page by an advertising network or other foreign domain).

In iOS 9, app developers can distribute a Content Blocker as part of their app. It remains inactive by default until the user turns it on, at which point Safari incorporates the blocker's rule set into its loading behaviors. Once activated by the user, Content Blockers affect not only how pages load in Safari, but also how pages load in any apps using Safari View Controller to incorporate web page rendering.

Developers can also present users with management settings within their app, allowing individuals to select what kinds of content they want to block, and then restrict or whitelist specific sites. Once new rules are defined, the app can then update Safari's behavior to reflect the user's desired settings.

A big shift for the web

Apple's new Content Blocker introduces an monumental shift in web publishing back to the original design of the web as an open platform for sharing information, particularly in a form that individual browser clients could freely interpret as they wished.

Rather than being a static content stream like television, the web was originally designed to send structured data from servers to web browsers in a form the end user could customize and liberally interpret. This enabled accessibility features and cross platform support, but also allowed automated robots to scan web pages and glean just what they wanted to find.

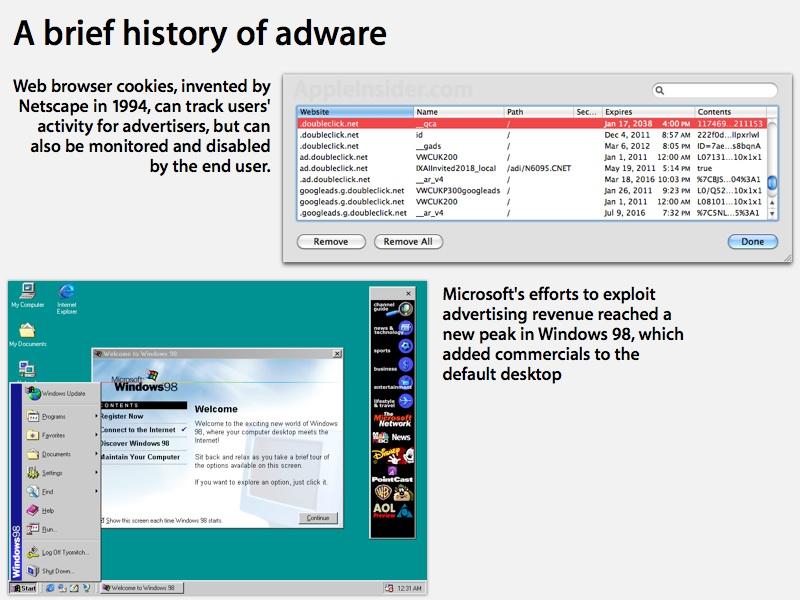

That includes Google's bots that index web pages for search. Because nobody wanted to pay for search, Google turned to search placement advertising to monetize its services. Google also began pulling data from web pages to position next to its ads in exchange for sending lots of web search traffic back to the original web pages. After its acquisition of DoubleClick and AdMob, Google also became a major vendor of display advertising on third party websites.

However, the value of display ads keeps dropping, meaning that publishers have to push more and more ads on their sites to earn any money. Ads are also getting more aggressive, with interstitials, popups and overlays that many users find maddening and intrusive.

Web ads are also getting smarter, in that that ad networks track user behaviors to sell advertisers placement in front of specific demographics where those ads are likely to perform better.

The primary way to become better at selling ads is to more narrowly target likely buyers, which has resulted in the web becoming inundated with tracking scripts and cookies to monitor and record where a user goes, compiling a dossier of their specific interests inferred from their browsing history combined with their social network likes and pluses.

Some of this aligns with users' own interests, enabling free services paid for by display advertising that is relevant and perhaps even interesting. However, there is a growing backlash among many users that don't want companies collecting large amounts of data about them, data that may be inadvertently published, stolen by malicious identity thieves or obtained by oppressive governments seeking to track their citizens to control dissent.

The potential impacts of content blocking for publishers

While ad blocking isn't new, and has long been used by Windows, Android and Mac users, the introduction of Content Blockers on iOS is noteworthy because the platform represents the largest audience of affluent mobile users. Google was recently reported to obtain 75 percent of its mobile revenues from iOS, despite the larger installed base of its own Android.

Rapid deployment of iOS releases also means that iOS 9 will reach many users rapidly, and the ease of installing and activating Content Blockers means that the world's most valuable platform of users will likely experience a significant drop in ad views, not to mention a critical loss of user tracking data on the web.

There are a number of likely consequences. First, because Content Blockers only effect the open web, publishers are likely to increasingly move toward delivering commercial content via apps, where it's easier to impose subscription paywalls, present display ads, or present an alternative monetization strategy. This could nudge the open web back toward its origins as a free repository of information with limited advertising.

Another direction might be a shift toward "native advertising," where content is positioned as having an ad sponsor, sometimes overtly being an advertorial. This blends the line between journalism and marketing, a line that's unfortunately already pretty grey on the web.

In a similar fashion, content publishers may seek to rely more upon affiliate deals or product placement, or other forms of advertising that can't be blocked. Some publishers are already moving web content toward videos, a television-like shift that makes it easier to reach users who don't like to read, while also presenting them with advertisements that they can't skip over.

Apple's iTunes Radio currently presents audio and video ads to monetize its free tier, while eliminating ads for subscribers, a model followed by many other app developers.

Apple's critics have been quick to imagine a cynical motive behind Content Blockers as a way to favor apps (which it offers to monetize with iAd) over the web (which it doesn't currently have any iAd program to address), but that doesn't take into consideration the fact that Google and a wide variety of other advertising networks also monetize developer's iOS apps.

The real difference between iOS apps and web pages is that Apple already restricts companies from distributing iOS adware titles or tracking users' location and device IDs within App Store titles, but didn't have a robust mechanism to similarly allow users to block annoying ads, cookies, tracking scripts and other content within Safari on iOS.

With Content Blockers, users will be able to selectively choose which sites they want to support and which content they don't want to keep seeing. That, in turn, is likely to push web publishers to dial back the amount of advertising they present, or to seek new, more effective ways to monetize their content.

This all happened before

A widespread user revolt against incessant, annoying ads wouldn't be anything new. In the 1980s, American broadcast television began cramming so much advertising into its content that users increasingly left for premium subscription channels or to watch prerecorded videos sold outright, rather than monetized by commercial interruptions.

A decade later in the 1990s, efforts by Yahoo and Microsoft to blanket the emerging web (and the Windows 98 desktop) with annoying, animated ad banners and sponsored push content opened up an opportunity for the newly incorporated Google, which began offering simple, relevant text ads that users found easier to handle. Google rapidly devoured online ad market share. It subsequently acquired DoubleClick and became the very thing it once offered an alternative against.

In 2010, Steve Jobs introduced iAd, an effort to similarly replace annoying ads within apps with interactive ads users might actually want to explore, knowing they are easy to dismiss and wouldn't simply dump them out of their app to follow an external link.

Apple's latest Safari 9 App Extension efforts to put users in control of what content they load on the web expands upon existing user privacy settings in Safari that allowed individuals to opt out of "cookies and website data" from third party sites, or from any source.

In 2012, Google devised a method to subvert these settings to track users anyway, resulting in a U.S. Federal Trade Commission investigation that was settled with a $22.5 million fine paid to the FTC followed by a second state settlement of $17 million. Google still faces a class action lawsuit in the U.K., after losing its appeal to have the case dropped.

In the U.S., courts dismissed a parallel class action suit, agreeing with Google that consumers didn't suffer any monetary harm from being tracked against their will. That may turn out to be a pyrrhic victory if Google's disregard for consumer privacy continues to result in valuable consumer demographics migrating toward Apple platforms, motivated by concerns over how their private data and online behaviors are being captured, tracked and monetized.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

Amber Neely

Amber Neely

Thomas Sibilly

Thomas Sibilly

AppleInsider Staff

AppleInsider Staff

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

28 Comments

That's an excellent point about 75% of Google's mobile revenue coming from iOS. If Apple were to ship a Google Ads content blocker by default they could deal Google a serious blow overnight. Though it would probably quickly become a cat and mouse game in terms of getting around the blocker. Regarding the app/web distinction: there were a couple of things at WWDC which make apps more like the web. One was universal linking, which allows apps to link to other apps like sites link to other sites, another was On Demand Resource (ODR) which could potentially allow apps to load "page at a time" similar to how web sites do. I think the reason that iPad growth slowed was that some of it's best features: light weight and all day battery life, were added to Apple laptops. The point being that you don't need to replicate an entire thing to compete with it, just the best bits. In the same way, the linking and on-demand aspects of the web (some of it's strongest features) are now coming to apps. Edit: come to think of it, another major feature of the web is platform independence, and another thing Apple announced at WWDC was "Bitcode" - a way for developers to upload their apps in an architecture neutral format.

My way of ”blocking ads“ on AppleInsider — was to get the iOS app subscription. For people like me, checking back with AI several times every day, this is great value for money. I absolutely love the clean look of AI on iPhone 6 Plus and iPad. Reading your long and excellent articles is a pleasure in such a well curated environment.

The video clip of Eric Schmidt is hilarious. On privacy he says that if you are concerned about people finding out about something you do maybe you shouldn't be doing it in the first place.... Example given? His 'open' marriage that he tries to keep secret??? Lol

That's an excellent point about 75% of Google's mobile revenue coming from iOS. If Apple were to ship a Google Ads content blocker by default they could deal Google a serious blow overnight.

Which the government could interpret as anti-competitive behavior? Not that it actually would be but the government seems to have put a bullseye target on Apple’s back recently. They are currently investigating the new music service before it even goes live. I personally think the government has decided that Apple has gotten too big for them to tolerate.

[quote] ...but also block invisible JavaScripts or other elements that web publishers or advertising networks use to track users and identify them across web properties. [/quote] Like AI's 80+ JavaScript trackers?