Ten Years of iPhone: the past present and future of Apple's blockbuster phenomenon

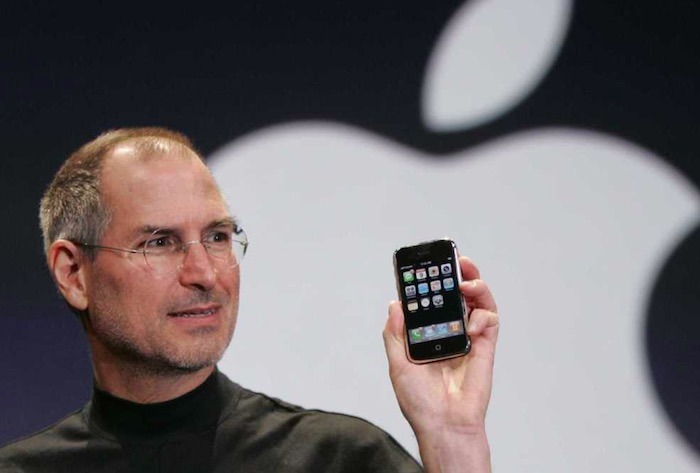

Ten years ago today, Steve Jobs unveiled the original iPhone during his keynote address at Macworld 2007. More than just a new product, the new device launched a radical new computing platform and rapidly accelerated the sophistication of mobile computing.

Why iPhone was a big deal: an iPod heir

Jobs introduced iPhone "a wide-screen iPod with touch controls, a revolutionary mobile phone and a breakthrough Internet device," coyly suggesting at first that Apple was set to introduce three new products. He then revealed that he was actually describing one new product: a mobile phone with the sophistication to act as both an iPod media player and as a powerful networked computing device.

The genius of the iPhone was that it irreducibly combined multiple families of technology that Apple uniquely possessed, making it difficult for competitors to copy.

Most obviously, iPhone leveraged Apple's previous five years of iPod development. By the end of 2006, Apple's half decade of iPod development had reached an impressive level of operational sophistication involving case, battery, display, storage and controller designs combined in a package that was then mass produced by the tens of millions and sold at a sustainable profit globally.iPhone leveraged Apple's previous five years of iPod development

Alongside iPod hardware, Apple had also developed an ecosystem within iTunes for selling music and video content and the beginnings of mobile software with iPod Games. Other companies— including big media firms— had largely failed in their own efforts to build anything like iTunes.

Rivals had also attempted to copy iPod in various ways, with Apple's biggest and most direct competitor Microsoft first attempting to create a new mobile Windows-like reference design platform for third party hardware partners it called PlaysForSure. As that failed to catch on, Microsoft then shifted toward making an overt copy of iPod it branded as Zune, which also failed to gain traction.

While critics incessantly predicted that Apple's iPod would be overrun by cheaper commodity lookalikes, Apple's iPod business just kept growing.

Why iPhone was a big deal: a macOS heritage

By 2004, some pundits began musing that the company should probably just throw away the Macintosh and focus on iPods. However, that observation was blindly ignorant of how valuable the Macintosh platform would become to the iPod's replacement.

Essentially, iPhone was a scaled down, ultra mobile Mac that could run powerful software, enabling it to act as an iPod, as a phone and also run new mobile applications, such as the company's Safari browser, Mail, Calendar, and its new Maps client that loaded images from Google Maps and presented them on an effortlessly scrollable and scalable view with pinned locations.

The number of consumer electronics companies that could attempt to successfully copy an iPod was a fairly short list, but the number of computing companies that could attempt to deliver a handheld computing platform of similar sophistication to iPhone was even shorter.

While it had 5 years of experience in building iPods, Apple had spent the last 16 years developing and selling macOS X, which built upon the company's previous years of experience in developing Macintosh computers, and also the decade-long development period of modern OS and software frameworks that had occured at Jobs' NeXT Computer, which Apple acquired at the end of 1996.

iPhone was the NeXT iMac

Apple's acquisition of NeXT envisioned that NeXT's sophisticated software (which among other things made it far easier to develop and maintain apps) could be combined with Apple's existing ability to design, mass produce and sell computing hardware.

However, Apple first needed to modernize and improve its existing operations. Jobs recruited Tim Cook from Compaq to do just that, resulting in a massive cleanup of the operational disaster that had been brewing during the early 1990s. After a year of slashing inventories and optimizing the supply chain, Apple introduced a new desktop computer aimed at filling the need for simple, safe Internet browsing: iMac.

Once iMac launched, Apple went on to enhance the rest of its product lineup, concentrating on notebooks as the trend toward mobility became clear. With its profit engines now operating, Apple was able to focus on upgrading its aging Mac software platform, taking full advantage of the technology acquired from NeXT.

One of the key new technologies Apple used built upon the advanced graphics model NeXT had introduced back in 1988. Unlike the classic Mac, which created a 2D graphical desktop of overlapping windows using QuickDraw routines (an approach copied by Microsoft for Windows), NeXT used Display PostScript to dynamically describe everything on the screen.

Apple decided to scrap DPS for licensing reasons for the new macOS X, and instead built a replacement graphics composition engine using PDF, called Quartz. Borrowing graphics technology developed for video games, Apple gave its new OS the ability to render true translucency and shadows in real time, enabling sophisticated animations where windows could be smoothly minimized into the Dock.

Apple introduced macOS X in 2001 and rapidly iterated a series of new software releases, even as it also launched its new iPod and began building out its iTunes media empire. Microsoft not only struggled to match the iPod, but also failed to introduce its own advanced graphics compositing engine for Windows until Vista arrived in 2006.

While Microsoft spent all those years trying to catch up to what Apple was delivering, it failed to predict that Apple itself was working on greater things that it had been announcing and releasing to the public.

Shortly after Microsoft belatedly introduced its new version of Windows that it had been talking about in public for years ("Longhorn"), Apple prepared to release its secret work on a rapidly advanced new hybrid of the iMac in an iPod sized form-factor: iPhone.

iPhone unraveled the Windows myth

Microsoft had been showcasing Windows tablets and a Windows Mobile reference platform for phones, without tremendous success. Unlike the modular PC industry— where Microsoft had successfully licensed Windows software as a generic platform capable of running desktop PC software across a wide variety of loosely integrated components— mobile tablets and phones required much tighter integration between software and hardware.

Conversely, Apple's biggest weakness historically had been that most of the unique features of its Macintosh systems could be quite easily copied by a large number of commodity hardware manufacturers, who could then undercut Apple on price using cheaper components and leveraging economies of scale.

With the iPod, Apple leveraged tight integration to deliver a product with some unique features that were harder to copy, principally including connectivity with iTunes. While Apple had maintained little effective control over Mac software, it could tightly control what content worked with iPods. It also developed a custom app platform for simple iPod Games sold through iTunes.

Few in the tech industry saw this as being an important shift. Instead, virtually everyone remained convinced that the only possible way to make money in consumer tech would be to copy Microsoft in licensing a software platform, or to build commodity hardware while racing to the bottom in pricing.

However, Windows licensing had really only proven successful in conventional PCs and servers. Tablets weren't catching on, Windows Mobile phones were not making money, and various other efforts by Microsoft to expand its licensing into copiers, media players, TV boxes and other areas had failed. By 2006, Apple had clearly proven that money could be made from selling integrated products: Macs and iPods

By 2006, Apple had clearly proven that money could be made from selling integrated products: Macs and iPods. When it introduced iPhone, it rapidly blew Windows Mobile out of the water before the end of that same year.

One primary reason: Apple had applied some of the same video game tricks that had rendered macOS X animated and "lickable" in the development of iPhone software, giving it an instantaneous response to finger touches and lag free performance in scrolling. This made existing smartphones look archaic in comparison, from Nokia's Symbian to Palm OS to BlackBerry.

iPhone caught multiple industries flat-footed

Apple's ability to pull off hardware and software magic with iPhone was closely related to its ability to tightly integrate its advanced software to the hardware capabilities of the new device. Despite being slow and limited by modern standards, the original iPhone packed far more processing power and RAM than existing smartphones.

At the same time, Apple also accounted for hardware limitations through the use of clever tricks, such as capturing photo data before the user touched the shutter, resulting in the appearance of photo capture faster than the hardware was actually capable of doing.

With iPhone, Apple launched scores of advancements— years of secret work— in one impressive package, rather than incrementally evolving the iPod into a phone, and then gradually giving it advanced computing features.

This not only delighted users with functional, desirable novelty, but it confounded competitors. All of the smartphone platforms that existed when iPhone was released were effectively knocked out of business within the next three years as they grappled with maintaining their existing products while scrambling to catch up with what Apple had released. All of the smartphone platforms that existed when iPhone was released were effectively knocked out of business within the next three years

Even ambitious attempts to remake their existing platforms failed. Palm's webOS, Nokia's open sourced Symbian, various Linux-based mobile platforms, BlackBerry OS 10 and Microsoft's Windows Phone 7 all raced against time while struggling for attention and relevancy.

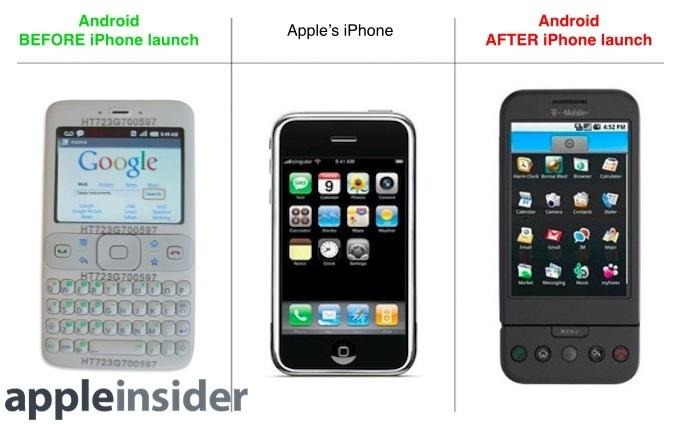

The mass failure of every other mobile platform left an opening for Google's Android, which promised to offer a Windows-like platform for third party hardware makers that would give them a product that looked and worked like an iPhone. However, that proved to be far more difficult than planned, largely because of Apple's advantages in tight integration.

Beyond phone makers, the general purposing computing platform of iPhone also helped virtually erase other entire industries, ranging from point and shoot cameras, to GPS navigators, to standalone accessibility devices.

iPhone also presented a dire threat to conventional computing: why sit at a desk using Google to search a web browser for information when you could instead walk around with a custom mobile apps that do exactly what you need to do?

Google follows Microsoft to be more like Apple

While Google had initially focused upon the threat to its advertising revenues potentially posed by Windows Vista, it quickly recognized Apple's iPhone as the new threat to its web search and advertising empire, and shifted its original plans for Android into an effort to kill the iPhone.

However, another important aspect of iPhone's success was that Apple was now selling its new handheld computer in massive scale at margins similar to the Mac. Rather than playing a minor role among PC makers in both volumes and revenues as it had with Macs, Apple was now selling a significant percentage of all smartphones globally and increasingly earning a majority of the industry's profits.

By 2010, Android was the only significant competitor left to Apple's iPhone sales. However, unlike Windows, Google wasn't really earning anything from giving away its Android software. Caught in a PlaysForSure-style conundrum, Google next copied Microsoft's Zune strategy of competing against its own licensees by launching its own Nexus-branded Android phone.

When that didn't work out, it copied Microsoft again by buying up a major licensee. However, Google's acquisition of Motorola turned out to be as spectacularly bad as Microsoft's acquisition of Nokia. Apple made the work of designing new hardware look easy. It wasn't.

Meanwhile, as Microsoft and Google frittered away billions of dollars in their parallel efforts to become more like Apple with tightly integrated mobile product design, Apple continued to invest billions of its profits into production capacity and proprietary technology, notably including advanced custom Application Processors, Touch ID, storage and battery technology.

As a result, ten years after it introduced the iPhone, Apple now sells over 200 million iPhones while Microsoft sells virtually zero and Google might sell as many as 2 million of its HTC-built Pixel phones this year.

iPhone monopolizes the premium market

The kind of phones Apple sells are also important. Leveraging its access to advanced proprietary technology, Apple designs and sells ultra premium iPhones with an Average Selling Price consistently near $650. Commodity Android smartphones have an ASP that's now close to $200, making them barely profitable for most manufacturers.

Even Google's Pixel, which is priced the same as Apple's iPhone, makes far less money because it lacks similar economies of scale. And Google also lacks access to the advanced proprietary technology Apple has developed or acquired.

The only company selling more smartphones than Apple is Samsung, but the majority of the phones it sells are low or middle tier models that don't make much money. As a result, despite selling around twice as many units, Samsung earns a fraction of the profits Apple does, even though Samsung sources much of its own components internally.

In 2014, Apple released iPhone 6 Plus as a new premium tier model, devastating the high end of Samsung's phablet phone sales. This year, the company is rumored to release a new ultra-premium tier offering advanced new technology in a bid to entice buyers to upgrade further, increasing ASP and profits in a market where unit volume growth has slowed to a halt. After ten years of defending its iPhone sales from competitive threats, Apple is in the enviable position of expanding its R&D and acquisition targets while facing sharply limited direct competition

What's next for iPhone

After ten years of defending its iPhone sales from competitive threats, Apple is in the enviable position of expanding its R&D and acquisition targets while facing sharply limited direct competition. Its old platform rival Microsoft is now an enthusiastic iOS apps partner.

Its former iPhone services partner Google, despite waging an all out war on iPhone, is now struggling to find reasons to maintain Android as a platform, even as Android itself continues to suffer from serious security issues and software update lethargy.

Its component supplier and phone rival Samsung has suffered through one of the most expensive, embarrassing flops in smartphones, and continues to struggle to expand its premium smartphone sales even as it gets pushed out of China and India by domestic low end phone vendors.

The phony rivalry champion of this year's CES, Amazon, has so far only failed spectacularly in launching its own Fire-branded smartphone, and the best that can be said of its challenge to Apple is that it sells a voice based appliance in minor volumes that is ripe to be assimilated into the general purpose smartphone.

However, Apple clearly faces threats of its own. Demand for smartphones has largely peaked in the West, and in many other emerging markets there are low end offerings that potentially threaten to disrupt mass market demand for premium smartphones.

It could be that in the future, Apple may need to reinvent the iPhone into a new form factor to match the demands of users as technology shifts, the same way it adapted the late 1990s iMac into the mid 2000s iPhone. While buyers currently appear to be trending toward phones with larger screens, it could be that wearables— or multiple wearable devices— could someday take the place of today's smartphone.

Another potential future market for Apple's personal computers could be integrated into transportation: using advanced technology, sensors, displays and user interfaces to radically reinvent the car into a computationally powerful machine that avoids both traffic and collisions while making the world smaller and easier to navigate.

Over the last decade, Apple has already remodeled the iPhone into two other products: first iPod touch, then a larger iPad capable of assuming many of the tasks of conventional PCs with less complication and greater mobility. Like iPhones, iPads have completely dominated the premium market for tablets and taken most of the available profits.

Technology developed for iPhone has also made its way into Apple's Macs, and has been used to develop new products such as Apple TV and Apple Watch.

Even without a major shift in demand for new form factors and shapes, iPhones will also continue to get more sophisticated, with new sensors, cameras, displays, incrementally better wireless networking, and new software features for communicating, capturing, creating and consuming content and information in new ways.

Daniel Eran Dilger

Daniel Eran Dilger

Mike Wuerthele

Mike Wuerthele

Malcolm Owen

Malcolm Owen

Chip Loder

Chip Loder

William Gallagher

William Gallagher

Christine McKee

Christine McKee

Michael Stroup

Michael Stroup

16 Comments

A really good piece. I think the problem Apple faces is that not marketshare, it's profit. Even though they sell a fraction of devices that Android manufacturers do, they've effectively bled the market dry of every spare bit of change.

In a few years there won't be much left for them to add to the smartphone, but by then they'll be in to the next big thing. No idea what that'll be. Chances are it won't be one single thing but smaller projects that'll make the unobservant claim that the company is out of ideas since Jobs passed away. It may even be larger projects that people can't see because they have no visible impact on consumers – selling clean energy for example. I'm hoping they do something huge, like set up their own broadband network. But we shall see.

"At the same time, Apple also accounted for hardware limitations through the use of clever tricks, such as capturing photo data before the user touched the shutter, resulting in the appearance of photo capture faster than the hardware was actually capable of doing."

What? And if so, it would be really interesting for a list of the tricks used. I don't doubt there was technical or design sleight-of-hand but it would be good to see a list of some narrative about them.

Thanks DED for great summary to date and avoidance of the fake news narrative so common to other tech journalists. Keep it up.

Apple needs to poach you for their PR department.

And ten years later the same crowd of naysayers is still blathering that Apple did nothing new, didn’t change anything, didn’t influence the existing phones at the time. That crowd still won’t concede one once of credit to Apple for changing the landscape of the mobile universe even though it’s just about unanimous opinion from all quarters that Apple put a huge dent in that cosmos. These revisionists are like those old geezers out in the desert in their trailers claiming they have proof the moon landings didn’t happen. Even today the competition tries to anticipate what Apple will do next and attempts to beat them to the punch.

I'll never tire of watching that presentation - the best reveal ever. imo